You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

In recent years there has been a paradigm shift in endodontics, where crown-down instrumentation has become more desirable than step-back in attempting to negotiate the length of an anatomical root. But no matter which method a clinician prefers, the end-goal remains the same: to reach the apical extent of the canal system in order to remove all tissue or microorganisms that may be causing disease. For almost 50 years, apex locators have augmented the clinician in achieving this objective. This article discusses the advantages and limitations of apex locators so that clinicians can become more comfortable and adept in locating proper canal length.

Determining Appropriate Working Length

To be able to determine correct working length, one needs to appreciate what that term truly means. As early as 1930, Grove determined that root canals should be obturated to the “junction of the dentin and the cementum and that the pulp should be severed at the point of its union with the periodontal membrane.”1 Since the cemento-dentino junction (CDJ) is the anatomical and histological landmark where the pulp ends and the periodontal ligament (PDL) begins, it would seem appropriate to fill the root canal up to that point. An in vivo study found that the most favorable conditions occurred when instrumentation and obturation remained short of the apical constriction. Despite the absence of pain, overextrusion of sealer or gutta-percha was found to always cause a severe inflammatory reaction.2

Still, to the average clinician, determining the working length was often only achieved with the aid of radiographs. However, this was a far more arbitrary method of length determination. An examination into the research performed by Kuttler, Dummer, and Pineda demonstrated that canal length could greatly vary.3-5 First of all, the anatomy of the apex changes with age, often due to hard-tissue deposition. Second, the apical foramen (or major foramen) does not often lie at the anatomical apex of the tooth. Third, the apical constriction (or minor foramen) can itself be highly variable in its appearance.3

For all tooth types, it was determined that the distance from the major foramen to the apical constriction was 0.5 mm in younger individuals and 0.8 mm in older adults.5,6 This variability could be due to many factors, including caries, apical disease, etc, but it illustrates that there is a difference in anatomical considerations due to age. Furthermore, early anatomical studies are what really fostered the common teaching practice of determining working length to be approximately 1 mm short of the anatomical apex.

For many years, this philosophy was deemed to be correct. But now, of course, dental professionals are able to realize its limitations. “Average” is merely a number representing the midpoint of a certain set of data points—it allows for half the points to be higher and half to be lower. So while this philosophy provides a key starting point, clinicians realize that most teeth have constrictions that fall close to the average distance from the foramen but not precisely where that average states it should be.

Second, as previously mentioned, the apical foramen usually does not lie at the anatomical apex. After orthodontic therapy, for example, roots can often undergo resorption, allowing for apices to appear blunted upon radiographic analysis. Similarly, replacement and inflammatory resorption can allow for a modification in apex location.7 Moreover, the constriction itself can be variable in appearance.8

Dummer classified the apical constriction into four separate types: traditional, tapering, multiconstricted, and parallel.5 Still, clinicians often believed they could locate this unique spot by means of tactile sensation. While Stabholz demonstrated that preflaring a canal could help locate it 75% of the time, Seidberg found that even experienced clinicians could only accurately locate the constriction 60% of the time.9,10

As a result, for many years radiographs were the method of choice for finding the correct working length. But they, too, had their limitations. They were 2-dimensional, even though the images they were capturing were obviously 3-dimensional. Additionally, they were technique-sensitive and open to subjective interpretation, and, at times, analyzing them was impaired by existing anatomy. Superimposition of the zygomatic arch could interfere with maxillary first-molar apices 20% of the time and maxillary second-molar apices 42% of the time.11 The zygoma, a torus, or natural root bifurcation could all contribute to increasing a clinician’s inaccuracy in locating the correct working length. And, of course, prior to digital radiography, radiation was an even greater concern.

The Development of Apex Locators

While preoperative radiographs are essential in helping to diagnose disease, determine anatomy, and locate working length, the electronic apex locator, in conjunction with radiographic films or digital images, can allow for even greater accuracy in obtaining length determination.

Using the earlier work of Custer and Suzuki, Sunada was able to develop a device that used direct current to measure canal length.12 However, using direct current led to some instability with measurement. Polarization of the file tip also altered readings. Improvement came several years later with the development of the first-generation apex locators. The Root Canal Meter used the resistance method and alternating current as a 150 Hz sine wave. However, the high currents often helped to illicit more pain.13

Second-generation apex locators began to use impedance measurements instead of resistance to locate working length. Inoue developed a change-in-frequency method, which allowed for beeping sounds when the apex was reached. Still, most second-generation apex locators failed to give accurate readings in both dry and wet canals.

Third-generation apex locators improved upon their predecessors by generating multiple frequencies to determine accurate canal length. With Kobayashi’s introduction of the Root ZX, erroneous readings in the presence of electrolytes were finally lessened. Kobayashi used a ratio method based on the principle that two electric currents with different sine wave frequencies would have measurable impedances that could be measured and compared as a ratio, regardless of the type of electrolyte in the canal.14

Still, the Root ZX and even newer fourth-generation apex locators (eg, Foramatron® by Parkell, Mini Apex Locator™ by SybronEndo, Root ZX® II by J. Morita) are not without their limitations. Inflammation has been demonstrated to adversely affect an apex locator’s readings. Intact tissue, blood, and exudate can all cause inaccurate readings by conducting electrical current, while caries and metal restorations can also lead to inaccurate readings. And some apex locators, like the Foramatron have demonstrated that they are more accurate when readings are attempted in the presence of sodium hypochlorite.15

Dentin debris or lack of patency can also affect an apex locator’s readings. While either small or larger files can both be used to accurately determine working length, clinicians often obtain a better result by using a larger diameter hand file. Constant recapitulation and irrigation are both necessary to remove dentin debris, allowing for more optimal readings. However, only the canal should be kept wet rather than the chamber.

There are ways, of course, to eliminate some of these pitfalls. Remember that as a tooth is shaped, especially by rotary instruments, its curved canal length will become shorter. Therefore, rechecking one’s measurements is often beneficial. Apical debris can be problematic in achieving both accurate readings and overall clinical success; thus, as much debris as possible should be removed via recapitulation and active irrigation. If an amalgam is skewing the readings, remove it entirely if possible. If it is not feasible to do so, hold the file away from the amalgam to record the measurement, then move it back once the accurate reading is achieved. Some burs come with plastic sleeves that can also be placed over a file so that the metal restoration does not contact the hand file itself. Similarly, coating the coronal aspect of a file, even with nail polish, can achieve a comparable result.

If a small file does not obtain the necessary reading, use a file that is one or even two sizes larger. Remember that readings work well when the canal is wet, not the chamber. If a reading is significantly off, use other methods of determining working length. For example, a large lateral canal may provide an early terminus reading. This is one reason why it is important to take the file beyond the foramen and then return it to proper working length.

Other means for locating working length include using radiographs, paper points, Endo-vac, etc. If a paper point is consistently “wet” at 19 mm, then that is likely the proper working length. If a working-length radiograph is taken and the file looks significantly short, it may be due to a lateral canal, resorbed apex, or some other anatomical anomaly.

Case Study

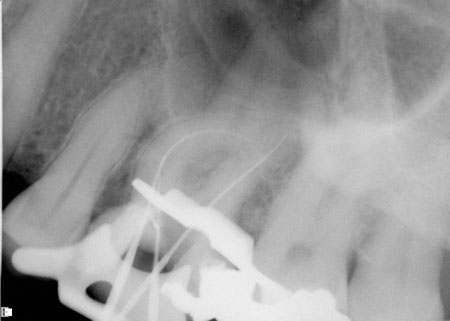

In the following case, the author used several of the above suggestions to properly determine working length. This tooth was diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis, and multiple visits were required to complete the case. While the maxillary sinus and zygoma often interfered in the author’s interpretation of the tooth’s anatomy, the tooth’s anatomy itself proved to be the largest obstacle to performing ideal root canal therapy (Figure 1). Originally, a periapical radiograph was taken to determine if the mesial canals actually curved as severely as the hand files had indicated. A periapical radiograph was then taken to approximate the measurements (Figure 2). Just from his own tactile sensation, the author came close to approximating the proper length of the canals but was not entirely accurate.

Figure 1 Preoperative radiograph demonstrating complex anatomy. |  Figure 2 An approximate working-length radiograph. |

Using the Foramatron, a length measurement was taken to determine precise working length. This apex locator is particularly easy to use because its display allows for good visibility of when canal length has been properly achieved. It is also straightforward, accurate and technique-friendly for both the advanced clinician as well as those using an apex locator for the first time.

For accuracy purposes, a digital periapical radiograph was taken to confirm the measurements (Figure 3). Notice that although the tooth had four canals, which is highly common for maxillary first molars, files were not placed in all four of them. Placing files in all four canals can sometimes impede a clinician’s ability to accurately visualize where a canal ends. In order to see all four canals it is more effective to take another digital radiograph to get an accurate measurement rather than take several poorly angled views.

Figure 3 Radiograph confirming lengths determined by apex locator. |

The case was completed, and a beautifully shaped and cleaned root canal was achieved (Figure 4). It should be noted that while many clinicians take both a preoperative and postoperative radiograph, it is the author’s opinion that an intermediate radiograph also be taken prior to completion of the root canal. This does not need to be a master-file radiograph; rather, a master-cone radiograph will suffice as confirmation that adequate length control was achieved (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The purpose for this is to allow the clinician to correct any discrepancies within the canal system prior to obturating the canal. By taking a master-cone radiograph, the clinician can see that the length is accurate and can avoid having a completed case that was obturated short because the cone was accidentally bent when it was placed into the canal.

Figure 4 Postoperative radiograph showing successful root canal. |  Figure 5 Master-cone radiograph depicting mesial and distal roots, prior to obturation. |  Figure 6 Another radiograph after downpack of palatal canal. |

While a master-file radiograph is also useful, it is often unnecessary when clinicians are confident that their readings from the apex locator are consistent with their determination for proper working length, based on their analysis of the original preoperative radiograph. In cases with unique anatomy, often both radiographs will prove to be of value. Fortunately, with the aid of this newer generation apex locator, the author was able to shape this canal system to its optimal length. This was possible in spite of two mesial canals that curved so far distally that the palatal root often impeded the author’s vision of the terminus of the mesial root.

Conclusion

It is critical to take a diagnostic preoperative radiograph prior to treating a tooth with non-surgical root-canal therapy. If the radiograph is diagnostic but difficult to gauge, an alternate angled PA should be taken; this can often provide equal or greater clarity. In addition, a bitewing radiograph should always be taken for additional clarity. To properly determine working length, an apex locator should be used in conjunction with working-length or master-cone radiographs. It should also be noted that a soon-to-be-published article in the Journal of Endodontics concludes that electronic apex locators are “more precise than digital radiography in detecting the apical foramen.”16

When experiencing problems in obtaining measurements with an apex locator, the suggestions provided in this article can be helpful. While apex locators are not meant to replace conventional radiographs, they are a valuable adjunct in properly reading the correct working length necessary to treat the entire root-canal system. Perhaps the only problem with them is their name, which may be a misnomer. As Dr. Steve Senia would say to me, “they don’t measure the apex, they locate the foramen.” While he is certainly correct, it may take another generation for his terminology, “foramen locator,” to be used.

References

1. Grove C. Why canals should be filled to the dentinocemental junction. J Am Dent Assoc. 1930;17:293-296.

2. Ricucci D, Langeland K. Apical limit of root canal instrumentation and obturation, part 2. A histological study. Int Endod J. 1998;31(6):394-409.

3. Kuttler Y. Microscopic investigation of root apexes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1955;50(5):544-552.

4. Pineda F, Kuttler Y. Mesiodistal and buccolingual roentgenographic investigaton of 7,275 root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;33(1):101-110.

5. Dummer PM, McGinn JH, Rees DG. The position and topography of the apical canal constriction and apical foramen. Int Endod J. 1984;17(4):192-198.

6. Stein TJ, Corcoran JF. Anatomy of the root apex and its histologic changes with age. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69(2):238-242.

7. Stock C. Endodontics-position of the apical seal. Br Dent J. 1994;176(9):329.

8. Gutierrez JH, Aguayo P. Apical foraminal openings in human teeth. Number and location. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79(6):769-777.

9. Stabholz A, Rotstein I, Torabinejad M. Effect of preflaring on tactile detection of the apical constriction. J Endod. 1995;21(2):92-94.

10. Seidberg BH, Alibrandi BV, Fine H, Logue B. Clinical investigation of measuring working length of root canals with an electronic device and with digital-tactile sense. J Am Dent Assoc. 1975;90(2):379-387.

11. Tamse A, Kaffe I, Fishel D. Zygomatic arch interference with correct radiographic diagnosis in maxillary molar endodontics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;50(6):563-566.

12. Sunada I. New method for measuring the length of the root canal. J Dent Res. 1962;41(2):375-387.

13. Gordon MP, Chandler NP. Electronic apex locators. Int Endod J. 2004;37(7):425-437.

14. Kobayashi C, Okiji T, Kaqwashima N, et al. A basic study on the electronic root canal length measurement: Part 3. Newly designed electronic root canal length measuring device using division method. Japanese Journal of Conservative Dentistry. 1991;34:1442-1448.

15. Meares WA, Steiman HR. The influence of sodium hypochlorite irrigation on the accuracy of the Root ZX electronic apex locator. J Endod. 2002;28(8):595-598.

16. Cianconi L, Angotti V, Felici R, et al. Accuracy of three electronic apex locators compared with digital radiography: an ex vivo study. J Endod. In press.

DISCLOSURE

This CE lesson was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Parkell.