You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

The nation’s growing geriatric population will require increasingly complex pharmacologic management of multiple disease states such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, diabetes, arthritis, and osteoporosis. As a consequence, polypharmacy in this population is often the norm. There are more than 15,000 currently approved prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, diagnostics, and intravenous supplementation products in the United States.1 Complaints of a feeling of dry mouth are one of the more common side effects of many these medications.

Xerostomia is defined as a subjective feeling of dry mouth resulting from a change in the consistency or a decrease in the production of saliva.2-4 Studies have found this condition to exist in 17% to 29% of sampled populations based on self-reports or measurements of salivary flow rates.5-8 Xerostomia is usually first reported when normal salivary flow decreases by 50%.9 Complaints of dry mouth are generally more prevalent in women and occur more frequently when patients are taking multiple drugs.3

This brief review describes normal salivary function, potential causes of salivary dysfunction, oral health concerns associated with hyposalivation, diagnostic tests, and options for patient care.

Normal Salivary Function

Saliva is produced by the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands, as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands distributed throughout the mouth. Daily production of saliva is estimated at 0.5 L to 1 L per day, and flow rates can fluctuate by as much as 50% with diurnal rhythms.9-13 Salivary flow rates are categorized as unstimulated (resting) and stimulated (when an exogenous factor such as eating activates the secretory mechanisms).9 Normal flow rates at rest are 0.3 mL/min and when stimulated increase to 4 to 5 mL/min.14 Although definitions vary, hyposalivation is usually defined as unstimulated whole saliva rates of 0.1 mL/min and stimulated rates of 0.7 mL/min.15

Both the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems provide innervation of the salivary glands. Parasympathetic stimulation, possibly of the M3 muscarinic receptor, induces more watery secretions, whereas the sympathetic system produces a more sparse and viscous flow.16 A sensation of dryness may occur after use of medications that block parasympathetic stimulation (parasympatholytics) as well as after sympathetic nervous system stimulation (ie, episodes of acute anxiety or stress), which cause a thickening of the salivary composition. Symptoms of a lack of saliva may be precipitated by dehydration of the oral mucosa that occurs when salivary output is decreased and there is a reduction in the layer of saliva that covers the oral mucosa because of a reduction in salivary secretions from either the major and/or minor salivary glands.11,17-20

Medication-Induced Salivary Dysfunction

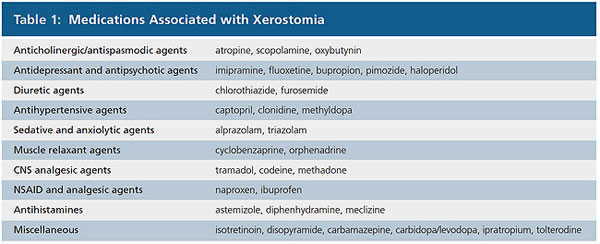

Although medications that inhibit parasympathetic activity and stimulate sympathetic activity are the most common xerogenic medications, other drug-induced causes of xerostomia may be a result of a reduction of blood volume (diuretics) and antihypotensive agents. It is similarly thought that agents that modulate nerve transmission within the central nervous system (CNS), such as antidepressant agents, inhibit autonomic stimulation of salivary glands. As summarized in Table 1, xerostomia is associated with a wide range of drug classes. The frequency and severity of complaint often varies from agent to agent within a drug class.21-23

Xerostomia is a common symptom of a variety of disease states such as Sjögren’s syndrome and other diseases with immunologic abnormalities. Patients with diabetes mellitus, particularly those who have poor glycemic control, are more likely to complain of xerostomia and may have decreased salivary flow.24-25 Significant hyposalivation is also reported after radiation therapy, bone marrow transplantation, and hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease.26,27 Anxiety, depression, or stress may also give rise to subjective symptoms of dry mouth.28,29

Establishing relative incidence rates for xerostomia for a particular drug is extremely difficult. As with other side effects, reported rates depend on how the information is accessed (direct vs open-ended questions), severity of concomitant adverse reactions, the disorder being treated, and the dose of the medication. Patients who are taking more than one xerogenic medication appear to have a higher incidence of dry mouth.21

Oral Health Concerns Associated with Hyposalivation

A reduction of saliva may lead to complaints of dry mouth, oral burning, soreness, or altered taste sensations. An increased need to drink water when swallowing, difficulty with swallowing dry foods, or an increasing aversion to dry foods may be reported.30 As the xerostomia progresses, inspection of the oral cavity may disclose an erythematous tongue with atrophy of the filiform papillae and a pebbled, cobblestone appearance. The oral mucosa may be erythematous and appear “parched.” Palpation of the oral mucosa may result in the finger adhering to the mucosal surfaces instead of readily sliding over the tissues. Application of a dry cotton swab at the parotid and submandibular duct orifices followed by external palpation of the glands may reveal delayed or inapparent salivary flow from the ducts.

The initial reduction in salivary flow may cause only symptoms of a loss of oral moistness and lubrication that, if unpleasant, may lead the patient to seek relief from a healthcare provider. After further loss of saliva, however, and as its physiologic functions become increasingly impaired, clinical abnormalities may become apparent.

A major complication of xerostomia is the promotion of dental caries, particularly cervical caries. This process is accelerated as a result of a reduction in oral irrigation and an inability to rapidly clear foods from the oral cavity, particularly if they contain sugar or acids. In addition, salivary proteins and electrolytes that inhibit cariogenic microorganisms and buffer oral acids, respectively, are diminished. The development of rampant caries at the cervical area has been observed within a few weeks after radiation therapy to the head and neck.31 Although loss of taste does not appear to be a major complaint among patients with xerostomia, the increasing sensation of dryness or difficulty with chewing and swallowing may result in the consumption of softer, more cariogenic foods. Frequently, patients will also resort to excessive consumption of sugar-containing confections or beverages in an attempt to stimulate salivary flow and keep the mouth moist.

Lack of saliva increases susceptibility to infection of the oral cavity and oropharynx by the opportunistic fungus Candida albicans.32 This may be augmented by the use of dentures, smoking, and diabetes.33 Manifestations of oral infection with Candida include erythema of the oral mucosa, white, curd-like patches that adhere to the mucosal surfaces, and inflamed fissures at the corners of the mouth (cheilitis).34

Diagnostic Tests

Asking several standardized questions regarding symptoms may help confirm salivary gland hypofunction. An affirmative response to at least one of the five following symptoms has been shown to correlate with a decrease in saliva: Does your mouth usually feel dry? Does your mouth feel dry when eating a meal? Do you have difficulty swallowing dry foods? Do you sip liquids to aid in swallowing dry foods? Is the amount of saliva in your mouth too little most of the time, or do you not notice it?35-37

Additionally, a number of supplemental tests are available that can be used to confirm the subjective manifestations of xerostomia. Salivary output can be measured, and a collected amount of less than 0.12 mL/min to 0.16 mL/min (unstimulated) has been suggested to be the criterion for hypofunction.13 Imaging modalities, including sialography and scintigraphy, have also been used to examine salivary gland function.38 Whether or not these tests provide definitive results, a patient’s report of xerostomia may, nevertheless, indicate palliative therapy for symptomatic relief.

Options for Patient Care

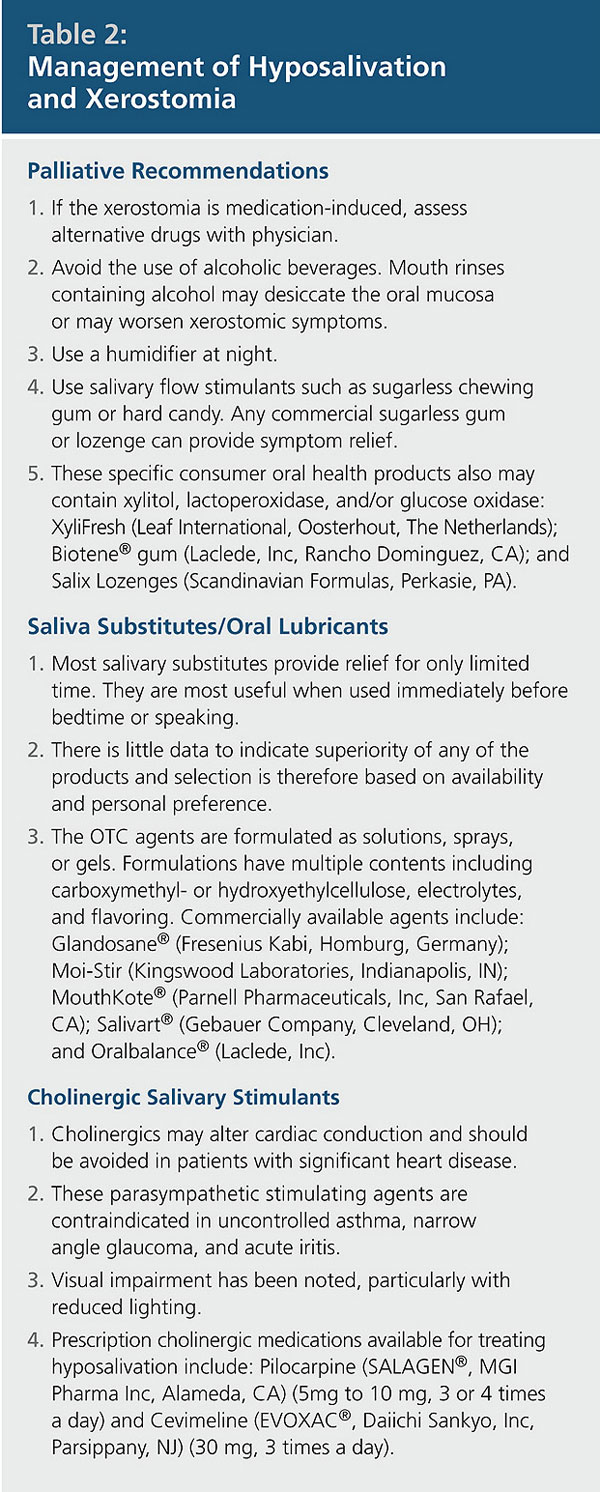

The general approach to patients with hyposalivation and xerostomia is directed at palliative treatment for the relief of symptoms and prevention of oral complications. If the xerostomia is a result of the side effect of a drug, substitution of an alternative medication can be recommended, but this course may not be beneficial if that drug has a similar mode of action.22 Modifying or altering the dosage regimen, such as between morning and evening, is another strategy that may relieve symptoms and improve salivary flow.22 Recently, carrying and sipping bottled water throughout the day has become a popular fad that may offer relief for affected patients. When at home, holding ice chips in the mouth will provide moisture and may also alleviate symptoms.

A number of commercial OTC products that can function as saliva substitutes have been developed specifically for patients with xerostomia. They are available in a variety of formulations, including rinses, aerosols, chewing gum, or dentifrices (Table 2). These products may also promote salivary gland secretions.39 Mouth rinses that contain alcohol may desiccate the oral mucosa and should be avoided.

Cholinergic agents stimulate acetylcholine receptors of the major salivary glands. The use of parasympathomimetic drugs such as pilocarpine hydrochloride can stimulate salivary gland secretions and has been shown to be effective for patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and after irradiation therapy or bone marrow transplantation.27,40-42 Another cholinergic agent, cevimeline hydrochloride, was recently approved for use in patients with hyposalivation.43

Patients using parasympathomimetic drugs may, however, experience a number of unpleasant side effects that may limit the efficacy of these medications.40 When conventional medical interventions do not provide satisfactory relief, or for those xerostomic patients who prefer alternative medical therapies, acupuncture may be beneficial for some patients.5,44-45 Patients who develop candidiasis secondary to xerostomia can be treated with oral or systemic antifungal drugs. Increasing oral moisture may also reduce the prevalence of this opportunistic infection.39

A number of therapeutic interventions are available for the control and prevention of dental caries. These primarily consist of rigorous attention to personal oral hygiene, strict adherence to a non-cariogenic diet, placement of sealants, and the application of topical fluorides. The latter may be useful if an increased incidence of coronal and/or root caries becomes apparent, even when fluoridated community water is available. This strategy may be effective for both caries prevention and possible reversal of decalcification. Supplements that contain sodium fluoride or sodium monofluorophosphate are available for professional application as well as for home use.46,47 These products can be applied in a variety of vehicles, including gels, rinses, lozenges, and chewable tablets.48 Interest is now focused on the use of varnishes that provide prolonged exposure to fluoride.49,50 This approach may prove to be useful for the prevention of caries associated with xerostomia.

Xerostomic patients wearing complete dentures are more likely to develop other complications, including pain from denture irritation and loss of retention.22,51 The greater risk for candidiasis in edentulous patients may contribute to their discomfort. Soft denture liners or incorporation of metal in the palate of the maxillary denture have been shown to be beneficial treatment options for some patients.52-53

Conclusion

The high prevalence of xerostomia and hyposalivation and the negative effect on a patient’s quality of life make it likely that the practitioner will encounter this condition on a regular basis. Often xerostomia results from the loss of saliva that may develop as a side effect from the use of medications. Treatment is primarily palliative, with emphasis on the use of saliva substitutes. Some patients may benefit from pharmacological stimulation of the salivary glands. The predominant complications that result from reduced saliva are dental caries, which require comprehensive dental management, and candidiasis, which can be treated with anti-fungal agents.

References

1. Hersh EV and Moore PA. Adverse drug reactions in dentistry. Periodontology 2000. 2007;45:1-34.

2. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 2001:398-404.

3. Fox PC, van der Ven PF, Sonies BC, et al. Xerostomia: evaluation of a symptom with increasing significance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;110(4):519-525.

4. Sreebny LM, Valdini A. Xerostomia. A neglected symptom. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(7):1333-1337.

5. Hochberg MC, Tielsch J, Munoz B, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of dry mouth and their relationship to saliva production in community dwelling elderly: the SEE project. Salisbury Eye Evaluation. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(3):486-491.

6. Gilbert GH, Heft MW, Duncan RP. Mouth dryness as reported by older Floridians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21(6):390-397.

7. Billings RJ, Proskin HM, Moss ME. Xerostomia and associated factors in a community-dwelling adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24(5):312-316.

8. Nederfors T, Isaksson, R, Mörnstad H, et al. Prevalence of perceived symptoms of dry mouth in an adult Swedish population—relation to age, sex and pharmacotherapy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(3):211-216.

9. Dawes C. Physiologic factors affecting salivary flow rate, oral sugar clearance, and the sensation of dry mouth in man. J Dent Res. 1987;66(Spec Iss):648-653.

10. Cooper JS, Fu K, Marks J, et al. Late effects of radiation in the head and neck region. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1141-1164.

11. Ghezzi EM, Lange LA, Ship JA. Determination of variation of stimulated salivary flow rates. J Dent Res. 2000;79(11):1874-1878.

12. Ship JA, Fox PC, Baum BJ. How much saliva is enough? ‘Normal’ function defined. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122(3):63-69.

13. Navazesh M, Christensen C, Brightman V. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of salivary gland hypofunction. J Dent Res. 1992;71(7):1363-1369.

14. Porter SR, Scully C, Hegarty AM. An update of the etiology and management of xerostomia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97(1):28-46.

15. von Bültzingslöwen I, Sollecito TP, Fox PC, et al. Salivary dysfunction associated with systemic diseases: systematic review and clinical management recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(Suppl S57):1-15.

16. Doods HN, Mathy MJ, Davidesko D, et al. Selectivity of muscarinic antagonists in radioligand and in vivo experiments for the putative M1, M2 and M3 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;242(1):257-262.

17. Dubnar R, Sessle BJ, Storey AT. The Neural Basis of Oral and Facial Function. New York: Plenum Press; 1978:391-393.

18. Wolff M, Kleinberg I. Oral mucosal wetness in hypo- and normosalivators. Arch Oral Biol. 1998;43(6):455-462.

19. Bretz WA, Loesche WJ, Chen YM, et al. Minor salivary gland secretion in the elderly. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(6):696-701.

20. Wu AJ, Ship JA. A characterization of major salivary gland flow rates in the presence of medications and systemic diseases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76(3):301-306.

21. Schein OD, Hochberg MC, Muñoz B, et al. Dry eye and dry mouth in the elderly; a population-based assessment. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(12):1359-1361.

22. Sreebny LM, Schwartz SS. A reference guide to drugs and dry mouth. Gerodontology. 1986;5(2):75-99.

23. Byrne BE. Oral manifestations of systemic agents. In: The ADA/PDR Guide to Dental Therapeutics. 4th ed. Chicago, IL: Thomson Healthcare; 2006:835-880.

24. Chavez EM, Taylor GW, Borrell LN, et al. Salivary function and glycemic control in older persons with diabetes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(3):305-311.

25. Moore PA, Guggenheimer J, Etzel KR, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus, xerostomia, and salivary flow rates. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92(3):281-291.

26. Bågesund M, Winiarski J, Dahllöf G. Subjective xerostomia in long-term surviving children and adolescents after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69(5):822-826.

27. Schubert MM, Sullivan KM, Morton TH, et al. Oral manifestations of chronic graft-v-host disease. Arch Int Med. 1984;144(8):1591-1595.

28. Bergdahl M, Bergdahl J. Low unstimulated salivary flow and subjective oral dryness: association with medication, anxiety, depression, and stress. J Dent Res. 2000;79(9):1652-1658.

29. Anttila SS, Knuuttila ML, Sakki TK. Depressive symptoms as an underlying factor for the sensation of dry mouth. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(2):215-218.

30. Loesche WJ, Bromberg J, Terpenning MS, et al. Xerostomia, xerogenic medications and food avoidances in selected geriatric groups. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(4):401-407.

31. Saliva: Its role in health and disease. Working Group 10 of the Commission on Oral Health, Research and Epidemiology (CORE) Int Dent J. 1992;42(4 Supp 2):291-304.

32. Samaranayke LP. Host factors and oral candidosis. In: Samaranayke LP, MacFarlane TW, eds. Oral Candidosis. London: Wright; 1990:66-103.

33. Guggenheimer J, Moore PA, Rossie K, et al. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and oral soft tissue pathologies: II. Prevalence and characteristics of Candida and Candidal lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(5):570-576.

34. Rossie K, Guggenheimer J. Oral candidiasis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1997;9(6):635-642.

35. Fox PC, Busch KA, Baum BJ. Subjective reports of xerostomia and objective measures of salivary gland performance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115(4):581-584.

36. Sreebny LM, Valdini A. Xerostomia. Part I: Relationship to other oral symptoms and salivary gland hypofunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:451-458.

37. Sreebny LM, Valdini A, Yu A. Xerostomia. Part II: relationship to nonoral symptoms, drugs and diseases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:419-427.

38. Fox PC. Differentiation of dry mouth etiology. Adv Dent Res. 1996;10:13-16.

39. Rhodus NL. Clinical evaluation of a commercially available oral moisturizer in relieving signs and symptoms of xerostomia in post-irradiation head and neck cancer patients and patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29(1):28-34.

40. Johnson JT, Ferretti GA, Nethery WJ, et al. Oral pilocarpine for post-irradiation xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(6):390-395.

41. Nusair S, Rubinow A. The use of oral pilocarpine in xerostomia and Sjögren’s syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999;28:360-367.

42. Nagler RM, Nagler A. Pilocarpine hydrochloride relieves xerostomia in chronic graft-versus-host disease: a sialometrical study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23(10):1007-1011.

43. Fox RI, Stern M, Michelson P. Update in Sjögren syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12(5):391-398.

44. Dawidson I, Angmar-Mânsson B, Blom M, et al. Sensory stimulation (acupuncture) increases the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the saliva of xerostomia sufferers. Neuropeptides. 1999;33(3):244-250.

45. Rydholm M, Strang P. Acupuncture for patients in hospital-based home care suffering from xerostomia. J Palliat Care. 1999;15:20-23.

46. Burrell KH, Chan JT. Systemic and topical fluorides. In: Ciancio SG, ed. ADA Guide to Dental Therapeutics. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: ADA Publishing; 2000:230-241.

47. Scheifele E, Studen-Pavlovich D, Markovic N. A practitioner’s guide to fluoride. Dent Clin North Am. 2002;46(4):831-846.

48. Wynn RL, Meiller TF, Crossley HL. Drug Information Handbook for Dentistry. 7th ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp Inc. 2001:1247-1248.

49. Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Goldstein JW, Lockwood SA. Fluoride varnishes. A review of their clinical use, cariostatic mechanism, efficacy and safety. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(5):589-586.

50. Newbrun E. Topical fluorides in caries prevention and management: a North American perspective. J Dent Educ. 2001;65(10):1078-1083.

51. Niedermeier WH, Krämer R. Salivary secretion and denture retention. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67(2):211-216.

52. Williamson RT. Clinical application of a soft denture liner: a case report. Quintessence Int. 1995;26:413-418.

53. Hummel SK, Marker VA, Buschang P, et al. A pilot study to evaluate palate materials for maxillary complete dentures with xerostomic patients. J Prosthodont. 1999;8(1):10-17.

About the Authors

Paul A. Moore DMD, PhD, MPH, Professor, Pharmacology and Dental Public Health, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

James Guggenheimer, DDS, Professor, Diagnostic Sciences, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania