You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

It has been 28 years since the first reports of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC’s 2007 HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report reveals that more than 1.7 million people have been infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) since the beginning of the epidemic, including more than 580,000 who have died, and an estimated 1.1 million who are living with HIV in the United States.1 More than 56,000 new HIV infections are estimated to occur annually—a 40% increase over previous estimates.2 The CDC also reports that approximately 25% of HIV-positive individuals remain undiagnosed.3 Approximately 36% of those who do test positive are identified late and progress to an AIDS diagnosis within 1 year.4 The CDC recommends offering routine HIV screening in alternative settings, which can include dental programs, to enable people to learn their HIV status earlier.

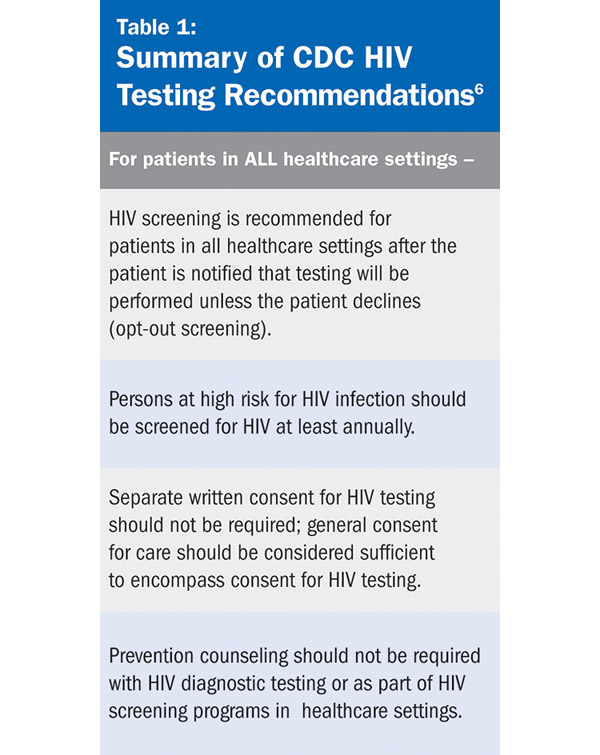

Early diagnosis of HIV leads to a healthier life, improves the outcomes of therapies, and is cost-effective over time.5 In addition, more than half of all new infections are transmitted by people who are unaware of their serostatus.6 In 2006, the CDC updated its HIV testing recommendations6 (summarized in Table 1) to include that all individuals aged 13 to 64 should be screened for HIV at least once and those at higher risk for infection should be tested annually.4

Why Screen in the Dental Setting?

Screenings for health-related conditions have long been a part of routine dental care. For instance, dental healthcare workers must be knowledgeable about hypertension, particularly detection and proper referral for treatment.7 More than one quarter of the US population has undiagnosed hypertension and does not show any obvious symptoms.8 The present recommendation is that blood pressure readings should be taken on all new patients and at recall appointments at least on an annual basis.7 Screening for oral cancer is a part of a routine dental examination, and the industry continues to develop tools to help assist in the detection of oncogenic changes early in the course of the disease.

The dental team has been an important part of HIV primary care since the early days of the epidemic, when up to 80% of all HIV-positive patients would present with an oral manifestation related to disease progression.9 Dental healthcare workers are often the first to recognize symptoms consistent with HIV and typically refer patients out to learn their status. However, the referring dental provider could not be confident that the patient would obtain an HIV test. Considering that advances in the medical management of HIV transformed this once certain death sentence into a chronic condition, it is time for a new dental public health strategy that incorporates the latest scientific advances, including rapid oral fluid–based diagnostics. The advent of rapid HIV-screening technologies allows individuals to learn their HIV status in approximately 20 minutes, well within the timeframe of a routine dental visit. People are more than twice as likely to receive their results when rapid HIV-testing technologies are used.10 The advantages of rapid HIV tests, particularly with oral fluid specimens, include increased acceptability of testing among populations at risk for HIV infection and increased receipt of test results.11 Proactive dental programs in both the public and private sectors have partnered with AIDS service organizations, community health centers, free health clinics, and hospitals to facilitate confirmatory testing and linkage to primary HIV care and appropriate support services.

Review of HIV Testing Methods

Standard HIV Test: ELISA

ELISA antibody testing looks for antibodies to HIV in the patient’s blood. After a patient has blood drawn, it is sent to a laboratory for processing where a laboratory technician places the serum in contact with particles of HIV in the presence of an indicating substance. In the ELISA test, if HIV antibodies are present, they will bind to the HIV particles and cause the serum to change color. If the ELISA test is positive, the laboratory will automatically perform a confirmatory test.

Rapid HIV Tests

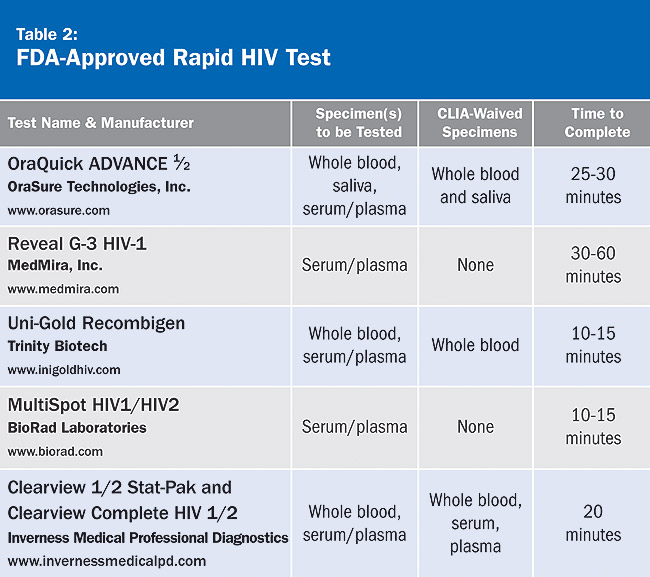

Rapid tests are similar to the ELISA test in that they look for antibodies in the patient’s blood, serum, or oral fluid. They are called rapid as the results are available within 1 hour or less compared to several days for ELISA. If a rapid test is positive, it must be followed up with a confirmatory test. For a complete list of FDA-approved rapid HIV tests, see Table 2, which appears courtesy of the American Academy of HIV Medicine.

The sensitivity (the proportion of people with a disease who are accurately identified by a test) and specificity (the proportion of people without a disease who are correctly identified by a test) of these tests ranges from 98.4% to 100%. A patient with a history of recent HIV risk behaviors should have a repeat rapid HIV test because it may take up to 3 to 6 months for HIV antibodies to be detected after exposure. Testing during this period may be indeterminate or give a false-negative test result.

Confirmatory Tests

Western Blot: This is the most widely used confirmatory test for HIV infection. Western Blot uses an electrophoretic technique that separates out specific HIV antigens. The Western Blot confirmatory test will rarely be indeterminate (and this most frequently occurs if the patient were recently infected). Immunofluorescence antibody (IFA): Infected HIV cells are fixed to a microscope slide. Serum is added and allowed to interact with HIV antigens. If HIV antibodies are present in the serum, a fluorescent label will light up the slide.

Patient Attitudes

Before instituting opt-out rapid testing at the Kansas City Free Health Clinic’s dental program, an attitude assessment survey of dental patients was performed. This pilot project assessed patients’ willingness to be screened for HIV with an oral fluid-based rapid test in the dental setting.12 Among 175 adult patients who were asked if they would accept a free oral fluid–based rapid HIV test in the dental program, 73% (P < .001) responded that they were willing to be screened.

Screening in Action

Dental programs in community health centers in Casper, Wyoming, and upstate New York were among the first in the United States to successfully incorporate HIV screening as a part of routine dental care. Other dental programs soon followed in Kansas City, New York City, Detroit, and Washington, DC. These forward-thinking programs understood that a significant percentage of the population accesses dental care during the course of a year that does not access medical care, leading to many missed opportunities to screen patients for diseases ranging from hypertension to HIV infection.

Before initiating rapid HIV screening, certain steps need to take place:

- Programs must become aware of state HIV testing laws and incorporate HIV testing into general consent processes or develop consent tools that will work in their setting. The national HIV/AIDS Clinicians’ Consultation Center (www.nccc.ucsf.edu) has up-to-date information on relevant state-specific testing laws, including information on informed consent.

- A Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA) application must be submitted if the dental program does not have one in place. Waived tests, such as HIV rapid testing and glucose monitoring, are not exempt from CLIA. Facilities that perform waived tests, such as dental offices, must apply for a CLIA Certificate of Waiver. (To receive a certificate of waiver under CLIA, a facility must only perform tests like the glucose meter or rapid HIV tests that the FDA and CDC have determined to be so simple that there is little risk of error. In addition, these tests are exempted from most CLIA requirements, and the programs that perform them do not receive routine inspection.) If a private dental office decides to implement rapid HIV screening, a CLIA application would need to be submitted along with the $150 biennial fee. Further information on the process can be located on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Web site located at www.cms.hhs.gov.

- Clinicians who will be performing HIV screening must receive training/certification on how to accurately perform the test. AIDS Education and Training Centers (AETC) is a good resource to learn about HIV testing. Further information can be found at the AETC National Resource Center (www.aids-ed.edu).

- Choose which HIV test will be used and how confirmatory testing and linkage to care will take place. It is very important to follow the manufacturer’s test instructions to control and maintain the product appropriately and to read the results within the specified time frame.

- Decide which personnel in the dental office will be involved in performing rapid HIV screening and gain buy-in from all staff members.

- Programs that perform rapid HIV testing must have in place linkage to care for confirmatory testing, counseling, and follow-up care. Dental programs providing rapid HIV screening must have knowledge of the private and public resources available for people living with HIV/AIDS in their communities.

As stated in a September 2005 editorial that appeared in the Journal of the American Dental Association, “It would be wrong to demand that all dental care providers perform HIV tests in their office. However, for the provider who will take the time to acquire the skills necessary to perform such a task, doing so could be a great benefit to society.”13 Dental programs presently screening for HIV have already made a significant impact in their communities above and beyond the vital oral health services they provide. The path has been outlined by trailblazing individuals and organizations across our nation. The question remains, how many will follow and take the lead in their community by helping HIV-positive people learn their status and enter into care?

Disclosure

HIV Dental Alliance receives grant/research support from Orasure Technologies, Inc.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Vol. 19. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2009.

2. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520-529.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Prevalence Estimates—United States, 2006. MMWR. 2008;57(39):1073-1076. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR. 2006;55:14. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006.

5. Walensky RP, Freedberg KA, Weinstein MC, Paltiel AD. Cost effectiveness of HIV testing and treatment in the United States. Clinical Infect Dis. 2007;45:S248-S254.

6. Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(4):446-453.

7. Herman W, Konzleman J, Prissant LM. New national guidelines on hypertension—a guideline for dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(5):576-584.

8. Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Hypertension. 2008;52(5):801-802.

9. Reznik DA, Bednarsh H. HIV and the dental team: The role of the dental professional in managing patients with HIV/AIDS. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2006;4(6):14-16.

10. Hutchinson AB, Branson BM, Kim A, Farnham PG. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of alternative HIV counseling and testing methods to increase knowledge of HIV status. AIDS. 2006;20(12):1597-1604.

11. Roberts KJ, Grusky O, Swanson AN. Outcomes of blood and oral fluid rapid HIV testing: a literature review, 2000-2006. AIDS Patient Care. 2007;21:621-636.

12. Dietz CA, Ablah E, Reznik DA, Robbins DK. Patients’ attitudes about rapid oral HIV screening in an urban, free dental clinic. AIDS Patient Care. 2008;22(3):205-212.

13. Glick M. Rapid HIV testing in the dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1206-1208.

About the Author

David A. Reznik, DDS, Chief, Dental Service, Grady Health System, Atlanta, Georgia; President, HIV Dental Alliance