You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Periodontal diseases are infections of the gums and supporting structures of the teeth. These diseases are as old as mankind. Human skulls from ancient civilizations show evidence of periodontal bony destruction.1 A Chinese book dated 2500 BC includes a chapter on dental and gum disease, and from 460 to 377 BC, Hippocrates prescribed his patients a dentifrice to prevent a “smelly mouth.” This paste was compounded of the head of a hare, the intestines of three mice, and ground marble and whetstone. It was to be rubbed on the teeth with greasy wool, and the mouth rinsed with water. The dirty wool was then soaked in honey, dill, anise, and white wine, and the liquid was held in the mouth several times a day.2 Dentistry has come a long way.

In spite of all the advances of modern dentistry, periodontal diseases continue to plague us and have replaced dental caries as the leading cause of adult tooth loss in the United States.3 The American Academy of Periodontology estimates that at least 75% of all adults have some degree of periodontal disease at some time in their lifetime, and 5% to 20% of adults will suffer from the severe form of the disease, periodontitis.4 Gingivitis, the first stage of periodontal disease, is nearly universal in children and teenagers, with varying degrees of severity.5 Former US Surgeon General David Satcher’s report Oral Health in America, published in 2000, called eriodontal diseases the “silent epidemic.”6

Patients may not understand the importance of maintaining a healthy “foundation” for the esthetic dental work they are seeking, or may not correlate inflammation in the mouth with overall health. Dental assistants can play a vital role in educating, preventing, and assisting in treatment of these diseases to increase patient oral and overall health, and increase case acceptance and success.

The Periodontium

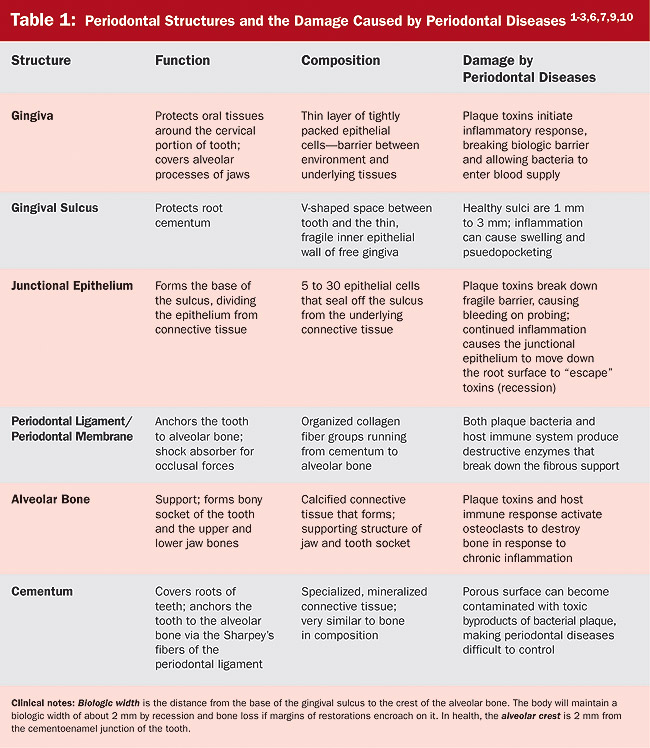

The periodontium surrounds and attaches the teeth to the alveolar bone, and is also sometimes referred to as the attachment apparatus (Figure 1).Without the health and function of these tissues, the teeth lose their support, and may not function effectively or may be lost.7-10

The Inflammatory Process

Periodontal diseases are a group of inflammatory diseases or infections of the surrounding and supporting structures of the teeth, the periodontium. From the Latin terms peri (around), odont (tooth), and itis (inflammation), periodontitis literally means inflammation of the structures around the teeth.7 Gingivitis and periodontitis are the two most common types of periodontal diseases, and their primary cause is bacterial plaque (oral biofilm), which initiates the inflammatory process. Gingivitis is reversible, with no permanent loss of supporting dental structures. Chronic gingivitis may persist for decades, and this chronic low-grade inflammation appears to have harmful long-term effects on the blood vessels and other tissues.11 Periodontitis includes inflammation of the gingiva and the deeper supporting structures, and is characterized by loss of connective tissue attachment and bone loss. Like gingivitis, chronic periodontitis can continue for years and triggers the same type of destructive inflammatory responses. Table 1 details how each structure of the periodontium is affected by periodontal diseases.

Although inflammation is designed to protect the body (host), most of the destruction of periodontal diseases, as well as other chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and type 1 diabetes, are caused by the inflammatory process itself.12 Following is an exploration of how a protective body mechanism becomes harmful.

Inflammation is a complicated series of events initiated when tissues and cells are damaged, either by invasion of foreign substances, microorganisms, immune substances, tissue necrosis, or trauma. It is a protective mechanism designed to remove the cause of the injury and to defend the life of the host, and ultimately, repair the damage and return the host to a normal continuing education state (Figure 2). The body’s response to inflammation is known as the host response.7,10-16 Inflammation is a local reaction involving vascular and chemical changes in the cells and tissue surrounding the injury. The classic clinical signs of inflammation are heat, redness, swelling, pain, and loss of function. For example, if a patient gets an ingrown toenail, the area around the inflamed area will feel hot, look red and swollen, and be so painful that the patient may not be able to walk properly. The inflammatory process attempts to “wall off” the infectious agent so that healing and normal function can occur.7,13,14,16

Two types of inflammation can occur: acute and chronic (Figure 3). Acute inflammation has a rapid onset and short duration. The body successfully defends itself against the invader, the damaged tissue is removed, and healing occurs. Acute inflammation is easy to recognize because it presents with the classic signs of inflammation. Chronic inflammation is prolonged and the continued presence of inflammatory white blood cells and their chemical products results in fibrosis and tissue necrosis. The classic signs of inflammation, especially pain, may not be present, so the condition may go unrecognized and untreated. This continued assault on the body’s immune system may cause an exaggerated host response that may result in damage to the area of injury and to the entire body.7,13,14,16

Scientists have identified more than 500 species of bacteria living in the mouth, but fortunately only a small percentage of those bacteria are associated with periodontal diseases. Unfortunately, left undisturbed, the bacteria multiply and grow into organized colonies called biofilms, which are very difficult to disrupt, especially in the protected environment of the gingival sulcus.17 As biofilms grow and become more complex, anaerobic and pathogenic bacteria thrive in the deeper layers. This group is called periodontal pathogens. These periodontal pathogens secrete chemical compounds that can break down the fragile lining of the sulcus, creating tiny ulcers that are responsible for the bleeding seen on probing, and allowing the bacteria to attack the deeper layer of connective tissue and get into the body’s blood supply. An excellent example of systemic bacterial invasion is infective endocarditis, and dental professionals can protect their susceptible patients by premedicating them with antibiotics before invasive dental procedures.

The tissue damage causes cells in the area to activate the immune system by sending white blood cells called neutrophils to build a wall to contain the bacterial invasion. The neutrophils also release chemicals, such as collagenase (an enzyme that destroys the protein structure of the bacteria), that damage the connective tissue of the host as well as the invader. If the neutrophils are successful, the biofilm and the immune system reach an uneasy balance, and gingivitis is the outcome.11,14,15,17

Permanent tissue damage to the supporting structures of the teeth (periodontitis) often occurs if the bacteria in the biofilm are able to overwhelm the neutrophil barrier, alerting the immune system of serious trouble. Macrophages [from the Latin term macro (large) and the Greek term phagos (one that eats)] gobble up invading bacteria, dead and dying neutrophils, and damaged tissue. Macrophages put the immune system on “red alert” by secreting chemicals such as prostaglandins (fatty acids that signal pain and increase inflammation), cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, matrix metalloproteinases that destroy injured tissue, as well as osteoclast activating factor, which destroys periodontal ligaments and bone. The diseased gingival sulcus deepens, resulting in periodontal pockets, and the alveolar bone begins to resorb in response to the inflammatory mediators. The proinflammatory chemicals attract additional immune cells to the area, and the inflammatory process is magnified. Although the purpose of the release of inflammatory chemicals is to destroy the invaders and to remove the damaged tissue, the response is nonspecific and all tissue in the area is at risk and can be damaged, including the fibers of the periodontal ligament and the bony support of the dentition. In most cases, after the invader has been destroyed, the inflammatory process slows down and moves into repair mode. Sometimes, however, the process goes into overdrive and destroys its own tissues, resulting in an autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis. This malfunction of the immune system is believed to cause the damage in periodontal diseases.11,14,15,17

Causative Factors

External Factors

Removal and control of bacterial plaque can greatly decrease the risk for chronic inflammation and periodontitis; however, the bacterial colonization is continuous, and patients must comply with a conscientious regimen of brushing, flossing, and dental visits or the inflammation will return.

Restorations that are difficult to brush or floss around may make it more difficult for patients to remove dental plaque. Placing a five-unit bridge and simply telling the patient to “keep it clean” sets the stage for failure of the bridge from recurrent decay or loss of bone support. Dental assistants can help patients by providing critical home-care information after placement of fixed prosthodontics or specialized restorations. The use of aids like floss threaders or interproximal brushes can help patients control the buildup of plaque biofilms around their restorations.

Patients often have the misconception that extraction of teeth is an easy way out, or that dentures will end their need for dental care. The forces of mastication strengthen alveolar bone, and after a tooth is extracted and the bony socket is not subjected to the forces of occlusion, bone resorption begins. Loss of sufficient alveolar bone caused by periodontal diseases will make retention of a complete or partial denture difficult, and placement of implants without sufficient bone is unlikely to be successful. Even single-tooth restorations, such as crowns, require adequate alveolar bone for support, so it is important to educate patients about the advantages of retaining their natural teeth.

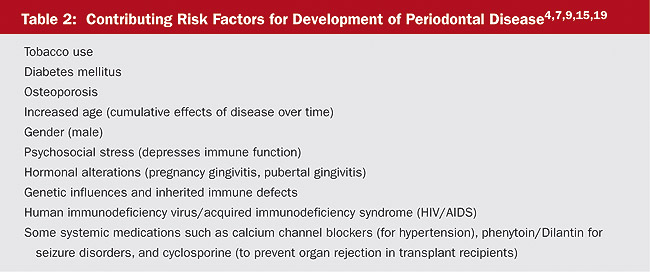

It also is important to note that smokers have a much greater risk of periodontal diseases, but usually do not display the classic signs of inflammation because tobacco causes vasoconstriction.18 Alerting patients to the harmful effects of smoking on the periodontium and suggesting smoking cessation may help smokers maintain their own dentition throughout their lifetimes. Although plaque accumulation and poor oral hygiene are the primary causative factors of periodontal diseases, other factors involving the individual’s genetics, systemic diseases, and immune defects put some patients at higher risk for developing these diseases (Table 2).7 Taking thorough medical histories, completing risk assessments, and educating patients about their risks can help prevent disease progression and motivate them to seek the additional care they may need.

Internal Factors

As recently as the 1980s, it was believed that plaque control alone could stop the progression of periodontal diseases, suggesting that patients who did not respond to treatment were guilty of poor home care. Based on current research, periodontal diseases now are believed to be the interaction between the challenge of the bacterial infection and the ability of the host’s immune system to contain the infection. Although bacterial plaque initiates the disease process, the individual’s immune response is the critical factor in the progression and severity of the disease. Some patients have extremely poor oral hygiene with large accumulations of bacterial plaque, yet only develop chronic gingivitis. Other patients may have very minimal amounts of plaque, yet develop severe periodontitis. The difference is the host response. Improving host response by eliminating risk factors and reducing bacterial infection is now considered the most effective method of treating periodontal diseases.7

Genetics play a role in the development of some periodontal diseases, especially severe and aggressive forms of the disease. A positive genetic marker for the IL-1 genotype may predispose smokers to a higher risk for developing periodontal diseases.20 Hereditary abnormalities in neutrophils (the first immune cell at the scene of bacterial invasion) or defective neutrophil function are linked to increased susceptibility to severe periodontal diseases, often at a young age. Down syndrome, Crohn’s disease, acute monocytic leukemia, and cyclic neutropenia are examples of this type of problem.7

Systemic diseases that suppress the body’s immune system, such as HIV and diabetes, greatly increase a patient’s risk of developing periodontal diseases, and patients with these conditions need to be carefully educated and monitored for disease progression. Any condition that affects the body’s ability to heal and repair itself also will have an adverse effect on the periodontal tissues.

Another internal factor in periodontal diseases is vitamin C deficiency. Vitamin C is important for the production of collagen and wound healing, and a deficiency can develop in as few as 20 days. Vitamin C also is necessary to maintain healthy blood vessels and to enhance iron absorption from red blood cells. A lack of vitamin C causes capillary fragility and an inability of the body to repair collagen (the primary material of the periodontal ligament) and bone, resulting in rapid loss of the teeth. Further, inadequate amounts of vitamin C during tooth development can cause defective enamel and dentin to be formed as well as cause the pulp to atrophy. According to recent studies, patients who have suboptimal levels of vitamin C are considered at increased risk for periodontal diseases.21

Your Active Role

Patients often ignore the signs and symptoms of periodontal diseases because they assume the signs are normal. We have all heard statements like: “My gums have always bled” or “Everyone in my family has bad gums.” But bleeding is a sign of active disease, and most people would be concerned if their arm bled after brushing it with a toothbrush. Unfortunately, patients often do not afford periodontal diseases this level of concern, possibly because they are rarely painful, and the diseases usually progress slowly over decades. Patients may assume that bleeding, receding gums, and tooth and bone loss are a natural part of aging. As professionals, we know that periodontal diseases are chronic diseases like diabetes, which can be controlled, but not cured, and that controlling it will require significant behavior changes as well as continued professional care.7 Without understanding the nature of these diseases, patients may not be motivated to change their behaviors or to seek the professional care they need to control it. Dental assistants can play a vital role in the educational process, helping patients to understand how to control their diseases and how to prevent further destruction. Your understanding of these diseases and how they can affect oral health can make the difference in your patients’ motivation and their health.

References

1. Phinney DJ, Halstead JH. Delmar’s Dental Assisting: A Comprehensive Approach.

2. Daniels SJ, Harfst SA. Mosby’s Dental Hygiene Concepts, Cases, and Competencies [updated].

3. Bird DL, Robinson DS. Torres and Ehrlich Modern Dental Assisting. 7th ed.

4. Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the

5. Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the

6. Melfi RC, Alley KE. Permar’s Oral Embryology and Microscopic Anatomy. 10th ed.

7. Nield-Gehrig JS,

8. Wolf HF, Hassell TM, Amodt GL, et al. Color Atlas of Dental Hygiene: Periodontology.

9. Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 9th ed.

10. Woodall IR. Comprehensive Dental Hygiene Care. 4th ed.

11. Hovliara-Delozier CA, Edwards J. Exploring the link between oral health and systemic health. Access. Apr 2006:15-20.

12. Research, Science and Therapy committee of the

13. DiGangi P. Oral-systemic link. Contemporary Oral Hygiene. 2007;7(1):12-17.

14. Mattila KJ, Nieminien MS, Valtonen VV, et al. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298(6676):779-781.

15. Guynup S. Our mouths, ourselves. Sci Am. 2006;295 (Spec Iss):4-5.

16. Bader HI. The oral/systemic link and the effect on patient compliance: a review. Dent Today. 2007;26(4):68-70.

17.Panagakos FS. Inflammation: its role in health and its mediation by chemotherapeutic agents. Continuing Education for the Healthcare Professional (CEHP), distributed by Sullivan-Schein, a Henry Schein Company, Course Reference No. 05AS2906B; 2005.

18. Ross PE. Invaders and the body’s defenses. Sci Am. 2006;295(Spec Iss):6-11.

19. Perry DA,

20. Genco RJ. The three-way street. Sci Am. 2006;295(Spec Iss):18-22.

21. Stegeman CA, Davis JR. The Dental Hygienist’s Guide to Nutritional Care. 2nd ed.

About the Author

Barbara L. Bennett, CDA, RDH, MS, Department Chair, Dental Hygiene and Dental Assisting Programs, Texas State Technical College Harlington, Harlington, Texas