You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

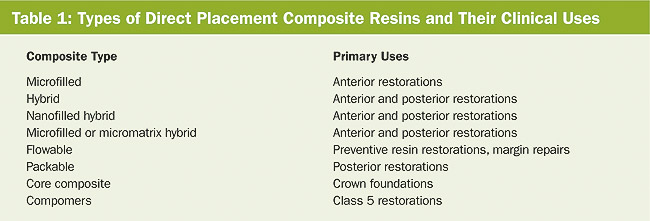

The esthetic appearance of composite resin restorations is based on the shape, color, and gloss achieved by finishing and polishing. Depending on your state's regulations, expanded-function dental assistants can polish a variety of types of composites to produce a range of esthetic appearances and lusters. Microfilled and nanocomposites can be polished to produce an enamel-like shine, while the conventional hybrid and packable composite resins, when used for posterior restorations, can be polished to feel smooth to the patient's tongue but do not require a high, enamel-like shine.

Even those dental assistants who are not currently able to polish composite resin restorations play an important role in both patient education and ensuring that the correct sequence of composite resin polishing instruments is being used to achieve the highest luster for each composite resin placed. Understanding the principles of polishing composite resins is even more important when the assistant is providing the final polish to a composite resin restoration.

Composite resins fall into a variety of classifications that relate to the chemical components. The chemical components, as well as the size of each component, affect the degree of polish each composite resin can attain. Microfilled composite resins are very polishable and, when polished correctly, look like enamel and glazed porcelain on a crown. The new generation of nanohybrid, microfilled hybrid, and micromatrix hybrid composites (those with very small filler particles, usually 0.4 µm in diameter) are also very polishable with a finished appearance similar to the appearance of enamel and glazed porcelain. These composite resins offer the additional benefit of enhanced physical properties for restorations that are under significant stress, such as posterior restorations and incisal edge repairs.

Choosing the correct composite resin for each restoration is important, but the final esthetic appearance of any composite resin restoration is based on the artistic abilities of the clinician to choose the correct shade or shades of composite resin to mimic the color and appearance of the teeth and to shape and contour the restoration. Today's composite resins have been formulated to be more sculptable, with minimal slump and very little tackiness, for ease of placement. However, composite resin restorations only adequately imitate the appearance of a tooth and/or adjacent teeth if rotary abrasives are properly used to finish and polish the restorative to its highest luster.1,2 Research has shown that the techniques for polishing composite resins to their optimal smoothness and gloss is product-specific and composite resin-specific.1-12

This article will discuss how to finish and polish composite resin restorations to esthetically pleasing shapes, colors, and glosses. In discussing composite resin restorations, this article will distinguish between composite resin restorations in the esthetic zone—those that must have a high luster-and composite resin restorations not in the esthetic zone—those that, while visible or on the lingual surfaces of teeth, only must be smooth so the patient cannot distinguish their smoothness from the remaining tooth structure.

Nanofilled Composites: A New Generation

Composite resins have changed significantly over the past 50 years, resulting in the current composites, which offer high polishability for a smooth finish and a wide range of shades for a better color match. The current generation of composite resins includes a number of categories for a variety of clinical uses (Table 1).

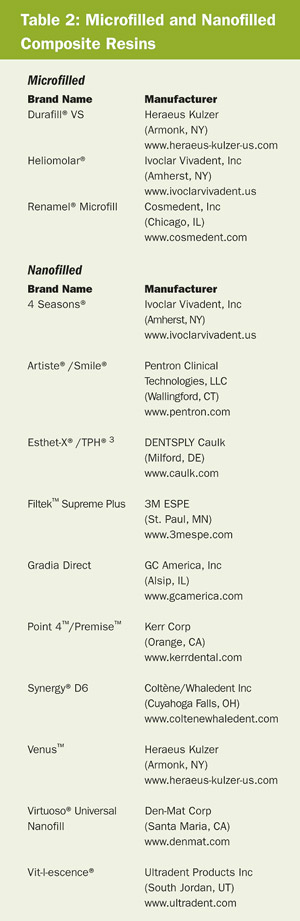

During the 1970s, microfilled composites offered high polishability with toothlike translucency (Table 2), but unfortunately they are radiolucent, except for Heliomolar® (Ivoclar Vivadent, Inc, Amherst, NY). This lack of radiopacity makes it difficult to diagnose caries at restoration margins and within cavity preparations. However, their high polishability and ability to maintain their luster over time make them a choice for anterior restorations. Because of their reduced strength, they are not generally a choice for chewing surfaces. Microfilled composites contain extremely small filler particles (0.04 µm colloidal silica particles) that are loaded into the composite's polymer matrix. Microfilled composites are generally loaded to 32% to 50% filler material by volume and, when compared with hybrid composite resins, have poorer physical properties, greater polymerization shrinkage, higher water sorption, and a higher coefficient of thermal expansion and contraction. Although microfilled composites maintain their gloss in high stress-bearing areas, they are susceptible to fracture,13 creating a need for a highly polishable composite resin with optimal physical properties for use in the anterior and posterior regions.

Micromatrix hybrid composite resins, introduced in the 1980s, offer this ability; they can be used for both anterior and posterior restorations, providing esthetics and chewing function. They combine ultrasmall filler particles (0.04 µmfumed silica) with microfine glass fillers (< 2 µm average particle diameter). Typically these composites are loaded to 58% to 75% filler material by volume and are radiopaque. This mixture of fillers creates excellent wear resistance when used for posterior teeth and, when compared with earlier macrofilled composites, high polishability.14 Regrettably, micromatrix hybrid composite resins cannot maintain their gloss when exposed to toothbrushing with toothpaste and cleaning with prophylaxis pastes.15-18

Recently a new generation of hybrid composite resins has been introduced that offers high polishability and toothlike translucency as well as the ability to maintain polish and luster.3,4 These composites have been categorized as nanofilled with filler particles ranging from 0.005 µm to 0.1 µm in diameter (Table 2). The introduction of nanofillers allowed manufacturers to create hybrid composite resins with physical properties equivalent to the original micromatrix hybrid composite resins-good handling characteristics and high polishability-that are also wear-resistant so they can be used to restore the occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth.3,4,19,20 No matter which of the more polishable composite resins-microfilled, micromatrix hybrid, or nanofilled-is selected for anterior restorations, the clinician can expect good color stability, stain resistance, low wear, and good polishability.14,19 While they can be used with basic shades, these new composites also have a complete range of incisal, enamel, and dentin shades for excellent esthetics when restoring anterior and posterior teeth.

Restoring with Composites

The sequence of polishing composite resins progresses from the coarsest abrasive to smoothest abrasive. Finishing and polishing devices and instruments can be classified as:

- coated abrasives;

- rotary cutting devices;

- rotary submicron particle diamond finishing abrasives;

- reciprocating abrasive tips;

- rubberized embedded abrasives;

- hand instruments; and

- abrasives suspended in a polishing paste.

No matter which abrasives are selected, the rule of coarsest to smoothest must be followed. Lists of instruments, devices, and materials for polishing composite resins are available at www.insidedentalassisting.com. Rotary polishers used for composite resins should not be used for metal restorations and vice versa.

The goal when placing any composite resin is that it will require minimal finishing and polishing. However, different classes of restorations generally will require different levels of finishing and polishing. For example, routine anterior and posterior restorations (Classes 1, 2, 3, and 5) often require minimal finishing, while larger, more involved restorations (Class 4, incisal edge repair, and complete facial veneering, especially for multiple teeth) often involve significantly more shaping and finishing, and therefore, more changing to different rotary instruments (burs, diamonds, finishing discs, and points).

Posterior Composites: Restoring Teeth Not in the Esthetic Zone

The dental assistant plays an important role during the placement, finishing, and polishing of composite resins. The instruments for use when finishing and polishing composites must be kept in the correct sequence to achieve the highest esthetics with any given composite. Broken or worn finishing burs and diamonds must be replaced. Specialized shapes to access different locations on the tooth allow for efficient finishing of composites. Routine Class 3 and Class 5 composite resin restorations, which are placed with minimal excess, often require only shaping and polishing with a small finishing bur or submicron diamond followed by a rubber abrasive disc, cup, or point. If a final luster is desired, polish the resin with polishing paste and a polishing cup.

Larger anterior restorations, such as Class 4, incisal edge repairs, and complete composite resin facial veneers, typically involve more gross shaping with finishing burs and submicron finishing diamonds on a high-speed handpiece, followed by additional finishing with abrasive discs and/or rubber points. To establish esthetic form to curved surfaces on long restorations that cover the full length of the tooth, use narrow, long finishing burs (Figure 1) or diamonds with safe-tipped ends (Figure 2).While finishing burs and diamonds can be used either wet or dry, the authors prefer using them dry and suctioning the composite dust throughout the procedure. The authors have found that by working with a dry field and a light touch, they can better visualize the shape and contour of the composite resin surface. Longer restorations also can be finished by judiciously using small sections of coarse and medium grit finishing discs. Most available discs have small metal hubs to avoid marring the composite surface by accidentally hitting the composite with the metal hubs of the disc (Figure 3). Some manufacturers have placed their discs on silicone sheaths that slip over the metal mandrel, totally eliminating the potential for marring the composite resin surface (Chipless Wheel, Shofu Dental Corp, San Marcos, CA; EP® Composite Polishing System, Brasseler USA, Savannah, GA).

If additional finishing of facial and lingual surfaces is desired, use a specialized rubber polisher, available in flame, disc, and cup shapes, on a latch-type contra-angle handpiece (Figure 4). These shapes will provide access to the varied contours of the tooth. When using abrasive systems, it is important to physically debride the surface of the composite resin with a damp cotton roll or gauze to free the surface of composite and abrasive debris. If only an air-water spray is used, some of the abrasive debris can remain on the restoration surface and interfere with attaining the smoothest polish with the next finest abrasive grit and instrument.

To finish and polish interproximally, use a gapped interproximal finishing and polishing strip covered with aluminum oxide abrasive particles or a metal interproximal finishing strip covered with submicron diamond particles. Occasionally, even with the use of a mylar matrix band, the restoration may bond to the adjacent tooth, literally splinting them together. In these cases, clinicians can use specialized accessories to separate the teeth without damaging the restoration. Clinicians can saw the teeth apart using an ultrathin stainless steel saw blade mounted in a handle, such as the CeriSaw® (Den-Mat Corp, Santa Maria, CA) (Figure 5). This miniature hacksaw with handle provides total control for gently sawing through the interproximal resin. When using a saw, place a gingival wooden wedge to protect the gingival papilla from accidentally sawing too far. Another option is a gapped diamond-containing metal finishing strip with saw teeth on the strip (Axis Dental, Irving, TX). Den-Mat Corporation has applied this concept to the CeriSaw by placing submicron safe-sided diamond strips in the handle to finish resin and porcelain veneer interproximal surfaces (Figure 6). The small handle that holds the abrasive diamond strip allows for ease of use and greater safety when finishing composites. There is less chance of cutting a patient's lip or the gingival tissue.

Sometimes margination is best accomplished by using a hand instrument or a specialized reciprocating handpiece with a flat abrasive paddle. Carbide-tipped hand instruments, restorative knives, or scalpel blades with shapes that allow for access to the restoration margin can be used to remove overhanging restorative material in a more controlled way than with rotary burs or diamonds.2,21 For hard-to-reach areas, such as the interproximal surface at the gingival margin, use a reciprocating handpiece with a flat lamineer abrasive tip.21,22 Specialized instruments, such as reciprocating handpieces, can help create highly demanding esthetic restorations (Figure 7).

To polish the composite resin surface to its final, most lustrous finish, use discs with the finest aluminum oxide abrasive available. Using a disc will not only smooth the resin surface, but also heat the surface, creating a high luster. This heating of the surface causes the polymer matrix to reach its glass transition temperature. This phenomenon gives composite resin restorations their glassy appearance.23,24 Another option is to polish composite resin restorations with specialized composite resin polishing pastes, which contain either very fine aluminum oxide abrasive particles or diamond particles. These polishing pastes should be used with foam cups, felt mounted on discs, or fine goat's hair brushes. If the surface of the restoration is smooth with no facial lobular form, discs work well. If the facial surface has anatomic variations of lobular form or striations, composite polishing pastes work best.23,24

Posterior Composites: Restoring Teeth Not in the Esthetic Zone

Posterior composite resin restorations have become more popular.While silver amalgam, cast gold, and porcelain-metal are still the standard for posterior restorations because of their durability, for routine-sized preparations, composite resins can now be viewed as alternatives to metal restorations,25,26 because these restorations (Class 2 preparations with an isthmus width of one-fourth to one-third intercusp distance) lessen the wear of the composite resin in function.27

The American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs stated that composite resin restorations allow for more conservative preparations, thereby preserving tooth structure. Their guidelines further stated that resin-based composites can be used for pit-and-fissure sealing, preventive resin restorations, initial Class 1 and Class 2 lesions using modified cavity preparation design, and for moderate-sized Class 1 and Class 2 restorations. The advantages of composite resins over silver amalgam are that composites are highly esthetic, reinforce tooth structure, and can conserve more tooth structure in their preparation design.28

Finishing and polishing posterior composite resin restorations follow the same principles as those for anterior composite resin restorations, with one exception. Because these restorations are not in the esthetic zone (ie, do not need to be highly lustrous when dry), they can be polished to a smooth finish that is indistinguishable to the patient from the tooth being restored when the patient rubs his or her tongue over the tooth/restoration surface. The restoration is smooth, but not shiny. For example, Figure 8 shows distal caries in a mandibular premolar. Once restored, the restoration will need to be finished and polished. As with anterior composite resin restorations, use a finishing bur (Figure 9) or ultrafine finishing diamond to marginate and shape the restoration. Then polish the surface of the restoration with either composite resin rubber (silicone) polishers (Figure 10) or specialized polishing brushes (Figure 11). A new generation of abrasive-impregnated polishing brushes is available in a variety of shapes and sizes that can be used for almost every posterior composite resin surface. These new brushes have become the composite polishers in these authors' armmentaria. Using these brushes in a right-angle-latch handpiece leaves no mess after finishing and polishing in one step. Even without creating a high luster, this finishing sequence produces a completed restoration with a high esthetic appeal (Figure 12). As with any posterior restoration, after finishing and polishing, the clinician must verify and adjust any occlusal discrepancies.

Clinical Success: Maintaining Composite Restorations

The gloss of the composite resin contributes to the overall esthetic appearance of the restoration. It is possible that, even if all the recommendations for finishing and polishing composite resins to their highest luster are followed, outside influences can deleteriously affect the smooth composite surface. Because of these potential adverse effects, composite resin restorations need to be reassessed for repolishing at every recall appointment. The dentist, hygienist, and assistant all need to be aware of potentially damaging effects of the pastes and stain removal devices used during routine hygiene visits, and should learn techniques for repolishing composite resin restorations using fine abrasive aluminum oxide composite resin polishing pastes and discs.

Conclusion

During the last several years highly polishable microfilled, micromatrix hybrid, and nanofilled composite resins have become available. These new composite resins are manufactured with physical properties that allow them to be used successfully in the anterior and posterior regions. With these new composites, some more convenient and innovative polishing systems have been introduced, including rubberized abrasives and abrasive-impregnated polishing brushes. However, many of the previously available instruments are still very useful with the newer composites. To attain the optimal finish for composite resins, it is important to follow manufacturers' recommendations. Using a systematic technique from finishing burs and diamonds, to abrasive discs, to rubberized abrasives, to composite resin polishing pastes, clinicians should be able to impart an enamel-like luster to composite resin restorations.

References

1. Barghi N. Surface polishing of new composite resins. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 2001;22(11):918-924.

2. Duke ES. Finishing and polishing techniques for composite resins. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 2001;22(5):392-396.

3. Stanford WB, Fan PL,Wozniak WT, et al. Effect of finishing on color and gloss of composites with different fillers. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;110(2):211-213.

4. Strassler HE. Product advances with direct placement composite resins: current state-of-the-art. Contemporary Esthetics. 2006;10(2):16-19.

5. Barghi N, Lind SD. A guide to polishing direct composite resin restorations. Compend Cont Educ Dent. 2006;10(2):16-19.

6. Ozgunaltay G, Yazici AR, Gorucu J. Effect of finishing and polishing procedures on the surface roughness of new tooth-coloured restoratives. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(2):218-224.

7. Reis AF, Giannini M, Lovadino JR, et al. The effect of six polishing systems on the surface roughness of two packable resin-based composites. Am J Dent. 2002;15(3):193-197.

8. Pratten DH, Johnson GH. An evaluation of finishing instruments for an anterior and a posterior composite. J Prosthet Dent. 1988;60(2):154-158.

9. Jefferies SR, Barkmeier WW, Gwinnett AJ. Three composite finishing systems: a multisite in vitro evaluation. J Esthet Dent. 1992;4(6):181-185.

10. Barkmeier WW, Cooley RL. Evaluation of surface finish of microfilled resins. J Esthet Dent. 1989;1(4):139-143.

11. Hoelscher DC, Neme AM, Pink FE, et al. The effect of three finishing systems on four esthetic restorative materials. Oper Dent. 1998;23(1):36-42.

12. Setcos JC, Tarim B, Suzuki S. Surface finish produced on resin composites by new polishing systems. Quintessence Int. 1999;30(3):169-173.

13. Goldman M. Fracture properties of composite and glass ionomer dental restorative materials. J Biomed Mater Res. 1985;19(7):771-783.

14. Strassler HE. Polishing composite resins. J Esthet Dent. 1992;4(5):177-179.

15. Strassler HE, Moffitt W. The surface texture of composite resin after polishing with commercially available toothpastes. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1987;8(10):826-830.

16. Serio FG, Strassler HE, Litkowski L, et al. The effect of polishing pastes on composite resin surfaces. J Periodontol. 1988;59(12):838-840.

17. Roulet JF, Roulet-Mjehrens TK. The surface roughness of restorative materials and dental tissues after polishing with prophylaxis and polishing pastes. J Periodontol. 1982;53(4):257-266.

18. Neme AL, Frazier KB, Roeder LB, et al. Effect of prophylactic polishing protocols on the surface roughness of esthetic restorative materials. Oper Dent. 2002;27(1):50-58.

19. CRA Newsletter. 2003;27(1):1-2.

20. Peyton JH. Direct restoration of anterior teeth: review of the clinical technique and case presentation. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2002;14(3):203-212.

21. Strassler HE. Interproximal finishing of esthetic restorations. MSDA Journal. 1997;40(3):105-107.

22. Strassler HE, Brown C. Periodontal splinting with a thin high-modulus polyethylene ribbon. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2001;22(8):696-704.

23. Strassler HE, Porter J. Polishing anterior composite resin restorations. Dent Today. 2003;22(4):122-128.

24. Jefferies SR. The art and science of abrasive finishing and polishing in restorative dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 1998;42(4):613-627.

25. Statement on posterior resin-based composites. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs; ADA Council on Dental Benefit Programs. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129(11):1627-1628.

26. Smales RJ, Webster DA, Leppard PI. Survival predictions of amalgam restorations. J Dent. 1991;19(5):272-277.

27. Strassler HE, Truskowsky RD. Predictable restoration of Class 2 preparations with composite resin. Dent Today. 2004;23(1):93-99.

28. Gaengler P, Hoyer I, Montag R. Clinical evaluation of posterior restorations: the 10-year report. J Adhes Dent. 2001;3(2):185-194.

About the Authors

Howard E. Strassler, DMD, FADM, FAGD, Professor and Director of Operative Dentistry, Department of Endodontics, Prosthodontics and Operative Dentistry, University of Maryland Dental School, Baltimore, Maryland

Rose Morgan, CDA, Dental Assistant, Postgraduate Prosthodontics, University of Maryland Dental School, Baltimore, Maryland