You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a trend away from the use of dental amalgam for the placement of posterior restorations to the use of adhesive composite resin. A major challenge when placing any Class II restoration is the establishment of an anatomically shaped and positioned proximal contact.1 For composite resins, this challenge is greater because of the handling characteristics and physical properties of composite resin. Development of an anatomically correct proximal contact is critical to success of a Class II composite resin restoration. There is a direct correlation between the type of proximal contact and food impaction, and between pocket depth and food impaction.2 Class II caries initiates just below the proximal contact; just as there is a correlation between pocket depth and food impaction in the proximal area, there is also a correlation between food impaction and recurrent caries at the gingival margin of existing Class II restorations. However, unlike amalgam, which can be condensed against a metal matrix and will hold its shape to establish proximal contact, composite resin is a viscous liquid with rheological properties that will not allow it to be pushed against a matrix band to deform the matrix band to establish a proximal contact.3-5

To ensure success with posterior composite resins, there is a need for optimal isolation, usually using a dental dam, to ensure an uncontaminated field for the adhesive technique. In most cases, the adhesive technique is multi-step and the area must be isolated from saliva and bleeding, and the time needed for the composite resin placement technique must be taken into account. Current clinical evidence supports etch-and-rinse (total-etch) adhesive systems and self-etch (SE) adhesive systems for adhesion of composite resin to Class I and II cavity preparations.6-11

A chief complaint among practitioners and patients with posterior composite resin restorations has been the rate of postoperative sensitivity especially when using total-etch adhesives. In many cases, postoperative sensitivity is seen at higher rates with first-time restorations and in younger patients, and a number of clinical studies have investigated postoperative sensitivity using both total-etch and self-etch adhesives.12-18 The results of these studies demonstrated no difference in postoperative sensitivity between adhesive types. In fact, the conclusion of one study stated that postoperative sensitivity may depend on the restorative technique and variability among operators rather than on the type of adhesive used.12

One area of inconsistency with total-etch bonding has been the bonding potential to desiccated dentin.19,20 The inherent chemical nature of self-etch adhesives is that they contain water; as such, because they are no-rinse, the dentin surface is left moist. This may account for the case reports of minimized postoperative sensitivity.21 Also, with self-etch bonding the variability between operators can be minimized by simplifying the technique of adhesive placement.17, 21

How can postoperative sensitivity be minimized? While the data in the aforementioned research studies clearly state that there is little difference in strategies to avoid postoperative sensitivity, there are some techniques that, in the author’s experience, can solve this dilemma. For cavity preparations that are of ideal depth, using a self-etching adhesive has been beneficial in reducing postoperative sensitivity. For preparations just barely into dentin, the author has also successfully used glutaraldehyde-based desensitizing agents in the cavity preparation after etching and before application of a bonding agent. For deeper preparations, the author has used glass-ionomer liners and flowable composite resins as liners with a decreased rate of postoperative sensitivity.

Restoring Class II Restorations

Clinical evidence has demonstrated that Class II composite resins have significantly higher rates of caries at the gingival margin when compared to amalgam restorations.22-24 The reasons for these significant differences in caries rates at the gingival margins of Class II composite resins relates to the technique sensitivity of some dentin bonding systems, polymerization shrinkage of composite resin, challenges in techniques placing highly viscous composite resin into proximal boxes without trapping air bubbles (leading to poor marginal adaptation), contamination of the tooth surfaces due to poor field isolation, and poor polymerization of the resin adhesive and composite due to inadequate curing light output25,26 and distance of the light guide from the gingival margin.27-29 Xu et al investigated composite-resin adhesion as the distance from the light guide increased. Their investigation was prompted by the number of studies demonstrating poor marginal seal and increased microleakage at the gingival margin of these restorations when compared to the occlusal enamel margins. Their conclusion was that when curing adhesives in deep proximal boxes with a curing light set at 600 mW/cm2, the curing time should be increased to 40 to 60 seconds to ensure optimal polymerization.30

Key points to light-curing Class II composite resins include:

- Check the light output. Less than 600 mW/cm2 of output requires doubling the curing time in the proximal box of a Class II. At least 1,200 mW/cm is the preferred light output.

- Have the light probe tip clean off any contaminants as close to the tooth as possible. Have a protective sheath covering the light probe and rest the probe on the posterior cusps.

- When placing the light guide, the light guide should be at a right angle (90º) to the tooth being restored, with the light probe touching the tooth.

- Cure for a minimum of 20 to 30 seconds in the proximal box for the adhesive and another 20 to 30 seconds for composite resin placement.

Achieving Predictable Proximal Contacts

An often-occurring problem with Class II composite-resin restorations has been the achievement of a predictable, anatomic proximal contact.9,31-33 This problem directly relates to the fact that composite resins are viscous materials that cannot be condensed and pushed against matrix bands in a predictable manner.3-5 Even the most viscous packable composite resins are liquids that can be moved but cannot be made dense enough to hold their shape in order to move a matrix band that would help to achieve proximal contact and adaptation through movement of the teeth during the placement process.34

Although the use of pre-wedging before tooth preparation can help to alleviate the deficiency of compensating for thickness of the matrix band,9,35 modifications in matrix design, type of metal used, thickness, and retainer system have been introduced to eliminate the problem of poor proximal contacts with composite resin. The most commonly used matrix for attaining proximal contacts has been thinner, dead-soft, stainless-steel matrix bands and specialized retainers either for use as a sectional matrix or as a circumferential matrix (Table 1). These bands are available either for use in a Tofflemire-type matrix retainer, a 0.001” dead-soft, stainless-steel Tofflemire-type matrix band, or as a circumferential retainer-less matrix. In the author’s opinion, these circumferential-type matrix systems are ideal for use with Class II MOD preparations and large preparations that are past the facial or lingual line angles.

Table 1: Partial Listing of Matrix Systems for Class II Composite Resins

| Matrix System | Manufacturer |

| Contact Sectional Matrix System | Danville Engineering |

| Automatrix | DENTSPLY Caulk |

| Palodent Sectional Matrix System | DENTSPLY Caulk |

| Composi-Tight Matrix System | Garrison Dental Solutions |

| Composi-Tight 3D Matrix System | Garrison Dental Solutions |

| Optramatrix | Ivoclar Vivadent |

| Supermat Matrix System | Kerr Corporation |

| Contact Perfect Matrix Bands | Miltex |

| Cure-Thru Anatomic Matrix Bands | Premier Dental Company |

| Cure-Thru Squeeze Matrix | Premier Dental Company |

| Triodent V Ring System | Triodent |

| Triodent V3 Ring System | Triodent |

| Omni Matrix | Ultradent |

| HO Bands | Young Dental |

For two-surface Class II preparations restoring only a single proximal surface, a sectional matrix system using an ultrathin, dead-soft, stainless-steel sectional matrix in combination with a ring achieves some additional tooth separation. A comparison of proximal contacts with a sectional matrix systems showed that the separation rings resulted in tighter proximal contacts.32,33 A significant problem with these ring-based systems is that many times the ring sits on top of the gingival wedge. This is problematic, especially for short-crowned teeth, because ring can easily dislodge and fly off, many times striking the practitioner in the face. Therefore, it is critical that clinicians wear eye protection to avoid damage from this possible projectile. Recently, two innovative ring systems using soft silicone have been introduced to address the frequency of ring dislodgement.

Besides thin matrix bands, specialized instruments have been introduced to assist in achieving a positive, anatomic proximal contact with Class II composite resins (Table 2). Among these specialized instruments are hand instruments that have a cone shape for applying lateral force on the matrix band at the contact area during light-curing.18 Other hand instruments also have been developed to achieve a similar result. While these devices can achieve the desired result, they are limited in that they do not fit all preparations. Some instruments are fitted over the light tip and can be inserted into the proximal box of the cavity preparation and allow for light penetration into the critical gingival area of the tooth preparation.14,37 Unfortunately, because of the tip’s design it is difficult to form the contact predictably in the correct anatomic location, and in some instances its size precludes its use in more conservative cavity preparations.

Table 2: Partial Listing of Specialized Instruments and Devices to Achieve Proximal Contact

| Instrument/Device | Manufacturer |

| Trimax | AdDent |

| Belvedere Composite Contact Former | American Eagle Instruments |

| Contact Pro Plus | Clinician's Choice |

| Lip Tip | Denbur |

| Proxicure Tips | Ultradent |

Case Report

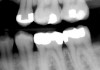

A patient presented for treatment with clinical and radiographic evidence of caries on the distal surface of the mandibular second premolar (Figure 1). The adjacent mandibular first molar had a defective amalgam restoration that was scheduled to be replaced with a core and prepared for a full crown at a future appointment. After administration of local anesthesia, a dental dam was placed. A sycamore wedge was firmly placed into the distal gingival interproximal embrasure before starting the preparation to achieve rapid separation of the tooth from its adjacent tooth to compensate for thickness of the thin, metal matrix (Figure 2). The tooth was prepared with a 245 bur with a high-speed handpiece and water spray. When restoring the proximal contact with composite resin, this author prefers to use a thin, dead-soft, stainless-steel matrix band that allows for shaping and achieving a positive, anatomic proximal contact. For this case the decision was made to use a silicone-covered split-tine ring with a sectional, thin, dead-soft, stainless-steel matrix. The silicone-coated ring is stable on the tooth and continues to apply pressure during restoration placement to ensure an anatomic proximal contact, while its shape allows for placement without interference from the gingival wedge. Also, the matrix has a tab extension that makes it easy to hold and place using a special forceps (Figure 3). Once the band was placed, an anatomic, flexible, polymeric wedge was placed using the same forceps.

One concern with self-etch adhesive systems is chemical stability and shelf life. Mix systems are more chemically stable than single-bottle systems. Some available self-etch adhesive systems include: Adper™ (3M ESPE), Brush & Bond™ (Parkell), Optibond® All-in-One (Kerr Corporation), and Xeno® (DENTSPLY). For this case, Brush & Bond was dispensed into a disposable dappen dish and activated with a microbrush activator by stirring the liquid with the microbrush. This system efficiently and effectively allows for the use of a chemically stable self-etch adhesive that is activated at chairside with the microbrush and will be used to apply the adhesive within the cavity preparation.

The Brush & Bond was painted into the cavity preparation (Figure 4) with the preparation kept wet for 20 seconds. The adhesive was air-dried to both evaporate the adhesive solvent and thin the adhesive in the preparation for 10 seconds (Figure 5). A high-intensity, ergonomic LED curing light was positioned to be touching the occlusal surface of the premolar at right angles to the proximal box. The adhesive was light-cured for 30 seconds due to the depth of the proximal box, with the gingival margin 5 mm from the light tip (Figure 6). One problem associated with Class II composite resin placement is achieving adaptation of the composite resin at the gingival margins. Some clinicians place a flowable composite in the proximal box before placing a more highly filled nanocomposite resin. Examples of available nanocomposite resins include: Beautifil® II (Shofu), Filtek™ Supreme (3M ESPE), Herculite™ Ultra (Kerr Corporation), HyperFil-DC™ (Parkell), and Kalore™ (GC America), For this case, a low-shrinkage, automixed, dual-cured, more-flowable, highly filled nanocomposite (HyperFil-DC) was used to restore the preparation using a bulk-fill technique.

The automix tip with a syringe-tip adapter allows the preparation to be filled from the inside out for better adaptation of the composite resin within the proximal box (Figure 7). After composite resin placement, the restoration was light-cured for 30 seconds. Since HyperFil-DC is a dual-cure composite resin, complete polymerization in the proximal box to the gingival margin is ensured.

With the matrix removed, the proximal surface was shaped with a long, needle-shaped finishing bur followed by shaping and finishing on the occlusal surface with a tapered, rounded-end finishing bur (Figure 8). The final finish and polish was accomplished with an aluminum-oxide silicon finishing cup (Figure 9). Another alternative to using a composite finishing point is the latest generation of diamond-impregnated composite-resin polishing brushes (Figure 10). The goal for finishing and polishing any posterior composite restoration is that the restoration feel smooth to the patient’s tongue and thus be acceptable.

In finishing a Class II composite resin, the most difficult-to-access margin of any posterior Class II restoration is the gingival interproximal margin. In the author’s experience, finishing strips do not work well on rounded or concave root and interproximal surfaces. Likewise, rotary handpieces with rotating diamonds and burs, often used in interproximal areas, are contraindicated because they can create unnatural embrasures and notched and irregular surfaces. An alternative instrument that can be used to remove excess resin in these areas is a 12A scalpel blade (Figure 11). The occlusion was checked and there was no need for any further adjustment. The final restoration demonstrates anatomic form and color (Figure 12).

Conclusion

The concepts and techniques described in this article can be used to provide patients with clinically acceptable, durable, and esthetic posterior composite resin restorations. To ensure the attainment of an anatomic proximal contact, pre-wedging, specialized matrices, and light-curing devices will eliminate the problems that have been encountered. Postoperative sensitivity with posterior composite resins can be minimized by using bondable resin or glass-ionomer liners for moderate-depth cavity preparations, glutaraldehyde desensitizing agents or self-etch adhesives. With the current evidence available, it is expected that these nanofill hybrid composite resin restorations will do as well as the conventional hybrid composite resins that have been used for more than 15 years.

References

1. Bauer JG, Crispin BJ. Evolution of the matrix for Class 2 restorations. Oper Dent (Suppl). 1986; 4:1-37.

2. Hancock EB, Mayo CV, Schwab RR, Wirthlin MR. Influence of interdental contacts on periodontal status. J Periodontol. 1980;51:445-9.

3. Strydom C. Handling protocol of posterior composites- part 3: matrix systems. South Africa Dent J. 2006;61:18-21.

4. Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Asscherickx K, et al. Do condensable composites help to achieve better proximal contacts? Dent Mater. 2001;17:533-41.

5. Liebenberg WH. The proximal precinct in direct posterior composite restorations: interproximal integrity. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2002;14:587-96.

6. Hickel R, Manhart J. Longevity of restorations in posterior teeth and reasons for failure. J Adhes Dent. 2001;3(1):45-64.

7. Wilder AD Jr, May KN Jr, Bayne SC, et al: Seventeen-year clinical study of ultraviolet-cured posterior composite Class I and II restorations. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11(3):135-142.

8. Lundin SA, Koch G. Class I and II posterior composite resin restorations after 5 and 10 years. Swed Dent J. 1999;23(5-6):165-171.

9. Strassler HE, Goodman HS. Restoring posterior teeth using an innovative self-priming etchant/adhesive system with a low shrinkage hybrid composite resin. Restorative Quarterly. 2002;5(2):3-8.

10. Strassler HE. Transitions from the familiar to the new: what bonding system should you use. Incisal Edge. 2003;8(7):6-7.

11. Strassler HE. Applications of total-etch adhesive bonding. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2003;24:427-440.

12. Perdigao J, Geraldeli S, Hodges JS. Total-etch versus self-etch adhesive effect on postoperative sensitivity. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1621-1629.

13. Akpata ES, Behbehani J. Effect of bonding systems on post-operative sensitivity from posterior composites. Am J Dent. 2006;19:151-154.

14. Perdigao J, Anauate-Netto C, Carmo AR, Hodges JS, et al. The effect of adhesive and flowable composite on postoperative sensitivity: 2 week results. Quintessence Int. 2004;35:777-784.

15. Unemori M, Matsuya Y, Akashi A, Goto Y, Akamine A. Self-etching adhesives and postoperative sensitivity. Am J Dent. 2004;17:191-195.

16. Browning WD, Myers M, Downey M, Schull GF, Davenport MB. Reduction in post-operative sensitivity: a community based study. J Dent Res (Special Issue B) 2006: 85:Abstract no. 1151

17. Casselli DS, Martins LR. Postoperative sensitivity in Class I composite resin restorations. In vivo. J Adhes Dent. 2006;8:53-58.

18. Stone CE. New instrumentation and technique for obtaining consistent proximal contacts in direct Class II composite restorations. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1994;6(5):15-20.

19. Kanca J. Improved bond strength through acid etching of dentin and bonding to wet dentin surfaces. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;123:35-43.

20. Gwinnett AJ. Moist versus dry dentin: it effect on shear bond strength. Am J Dent. 1992;5:127-129.

21. Lee R, Blank JT. Simplify bonding with a single step: one component, no mixing. Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice. 2003;7(5):45-46.

22. Bellinger DC, Tractenberg F, Barregard L, et al. Neuropsychological and renal effects of dental amalgam in children: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1775-1783.

23. DeRouen TA, Martin MD, LeRous BG et al. Neurobehavioral effects of dental amalgam in children: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006; 295:1784-1792.

24. Bernardo M, Henrique L, Martin MD, et al. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite resin restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2007;138:775-783.

25. Hinoura K, Miyazaki M, Onose H. Effect of irradiation time to light-cured resin composite on dentin bond strength. Am J Dent. 1991;4:273-276.

26. Rueggeberg FA, Jordan D. Light tip distance and cure of resin composite. J Dent Res. (Special Issue A) 71:188 abstract.

27. Felix CA, Price RB. Effect of distance on power density from curing lights. J Dent Res. 2006;85 (Special Issue B) IADR abstracts: abstract no. 2486.

28. Pilo R, Oelgresser D, Cardash HS. A survey of output intensity and potential depth of cure among light-curing units in clinical use. J Dent. 1999;27:235-241.

29. Pires JA Cvitko E, Denehy GE, Swift EJ. Effects of curing tip distance on light intensity and composite resin microhardness. Quintessence Int. 1993;24:517-521.

30. Xu X, Sandras D, Burgess JO. Shear bond strength with increasing light-guide distance from dentin. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2006;18:19-28.

31. Christensen GJ. Amalgam vs. composite resin: 1998. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998.129:1757-1759.

32. Loomans BA, Opdam NJ, Roeters FJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial on proximal contacts of posterior composites. J Dent. 2006;34:292-297.

33. El-Badrawy WA, Leung BW, El-Mowafy O, et al. Evaluation of proximal contacts of posterior restorations with 4 placement techniques. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:162-167.

34. Leinfelder KF, Bayne SC, Swift EJ, Jr. Packable composites overview and technical considerations. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11:234-249.

35. Hilton TJ. Posterior esthetic restorations. In: Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry. 2nd Ed. Eds. Summitt JB, Robbins JW, Schwartz RS. Hanover Park, IL: Quintessence Books; 2001:260-305.

36. Loomans BA, Opdam NJ, Roeters FJ, Bronkhorst EM, et al. Comparison of proximal contacts of Class II composite restorations in vitro. Oper Dent. 2006;31:688-693.

37. Ericson D, Derand T. Reduction in cervical gaps in Class II composite resin restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:33-37.

About the Author

Howard E. Strassler, DMD, Professor, Division of Operative Dentistry, Department of Endodontics, Prosthodontics and Operative Dentistry, University of Maryland Dental School, Baltimore, Maryland

Erin Ladwig, BS, Dental Student