You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Decorative piercing of facial skin and oral tissues has become increasingly popular in the past decade.1 Gold, silver, stainless steel, glass, and acrylic are the materials most widely used for such jewelry, with most styles falling within the categories of barbells, rings, and studs2 (Figure 1). Oral piercing locations gaining in popularity include the cheek, frenum, and uvula. Lip piercing in the United States dates back to some of the first facial skin piercing documented. During the last decade, lingual piercing has become the leading oral piercing performed at tattoo parlors.2 A similar increase has been seen in the number of published articles and case studies concerning complications from oral piercing.

Many piercing salons may provide only minimal training or infection control protocols to practitioners. Therefore, it is not surprising that most complications occur immediately after surgery. The most commonly reported and most serious short-term complication is infection.3 Oral infections, if not treated appropriately, can lead to severe complications, such as Ludwig’s angina.3 Other reported symptoms and/or complications of piercing include pain, prolonged bleeding, nerve damage, swelling, compromised airways, infection, and transmission of bloodborne viruses such as HIV, hepatitis (B, C, D, and G), herpes simplex, and Epstein-Barr.3-5 Loss of the barbell within the mucosa also has been reported.3

Complications arising from long-term use of oral piercing jewelry are not as frequently reported as short-term complications. Some long-term complications reported in the literature include interference with speech and mastication, and dislodgement and aspiration of studs and posts.6 Several publications also have documented soft- and hard-tissue damage.2,6,7

In 2002, Campbell and colleagues reported on lingual gingival recession and tooth chipping over time when using a barbell tongue device.7 Effects on oral tissues were assessed at 0 to 2 years, 2 to 4 years, and 4+ years. The most significant finding was that increased usage over time was associated with a higher prevalence of lingual recession in the mandibular anterior dentition and tooth chipping in the posterior dentition. No subjects in the 0-to-2-year group exhibited lingual recession, but recession was observed in 50% of the subjects in the 2-to-4-year and 4+ years groups.

Mandibular incisors were the most frequently affected teeth. In 4 cases, 2 of which involved participants with labrettes, facial gingival recession was evident. Two subjects (both in the 4+ years group) exhibited lingual recession and tooth chipping. The 4+ years group exhibited the most lingual recession, which ranged from 2 mm to 5 mm. Because the subjects exhibiting recession appeared to have limited, if any, calculus accretions on the lingual aspect of the involved teeth, they concluded that this reinforced the notion that mechanical action of the tongue device during protrusion was responsible for the tissue damage observed.

Campbell additionally reviewed 21 published case reports that included gingival lesions as one of their findings. Patients in these reports had used the jewelry from 6 months to 2 years. The most reported complications were tooth chipping or tongue swelling.

The following case presents adverse oral effects observed after 12 years of oral piercing jewelry use in a 28-year-old woman with 2 tongue hoops and a mandibular labrette.

Case Report

A 28-year-old woman presented to the University of Florida College of Dentistry’s department of periodontology with the chief complaint of “loose hurting teeth” in the lower anterior sextant. The patient had worn 2 lingual hoops and a mandibular labrette in the form of a bar for the previous 12 years (Figure 2). She reported smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day for 14 years. The remainder of her medical history was unremarkable.

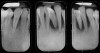

The initial periodontal evaluation included intraoral examination and a full mouth series of radiographs. These revealed severe periodontitis, localized to the lower anterior teeth (Figure 3), an unusually severe condition in an otherwise healthy young adult. Tooth No. 24 spontaneously exfoliated soon after the initial visit, as shown in the photograph taken 2 weeks after the initial visit (Figure 4). Probing depths along remaining teeth in the mandibular sextant ranged from 3 mm to 7 mm, with obvious recession and moderate to severe mobility. Plaque and calculus deposits were apparent interproximally and lingually, along with bleeding on probing. Pulp vitality was confirmed. Other areas, excluding the mandibular anterior sextant, exhibited minimal periodontitis, plaque accumulation, and marginal inflammation.

Occlusal patterns are inconsistent with the severe attachment loss around the mandibular anterior teeth. However, incisal chipping was evident on tooth No. 8 (Figure 4). Also apparent was perioral scarring, typical of intraoral piercing.

The patient mentioned awareness of disease progression while wearing her intraoral jewelry. As recommended, she completely discontinued oral jewelry use, and is considering future treatment, including regenerative periodontal surgery, orthodontic treatment, and thorough periodontal maintenance, including reinforcement of adequate oral hygiene techniques and use of fluoride for prevention of decay and root sensitivity.

Discussion and Conclusion

Attitudes toward body piercing, tattooing, and other forms of irreversible scarring and cosmetic surgeries have changed in the past decade. An internet Google search entitled “body piercing” revealed 1,590,000 entries, many of which were advertisements. Today, patients with various piercing locations and tattoos are seen in virtually every medical and dental practice.

Postoperative complications after piercing may involve redness and swelling, throbbing pain spreading to surrounding tissues, or a sensation of warmth at the site. Infection may be caused by improper cleaning, poor nutrition, and/or handling of the site with improperly disinfected or unwashed hands. Other contributors include allergies to metals, misplaced piercing locations, and inappropriate designs or sizes of the new jewelry. Short-term intraoral infection routes can potentially spread quickly and have severe consequences. Longterm implications resulting from jewelry use may include initial disturbances in speech, taste, and swallowing, cysts resulting from cross-contamination from jewelry sharing, erosion/attrition/abrasion of the dentition, and osseous destruction from the jewelry’s continuous traumatic irritation.

Long-term effects resulting from placement and wearing of oral jewelry have only recently begun to be studied. This case of a young woman with no evidence of periodontitis other than that associated with intraoral jewelry use illustrates one such long-term adverse effect. The unusually rapid periodontal destruction seen in this case may be considered aggressive periodontitis, in which attachment loss is 10 to 20 times faster than chronic periodontitis.

Along with inadequate oral hygiene and repeated trauma associated with the mandibular labrette and tongue rings, she had physically traumatized teeth, clearly contributing to the unusually severe periodontal destruction seen adjacent to the mandibular anterior dentition. As a single entity, trauma from occlusion has not been shown to induce periodontal tissue breakdown. However, this case may demonstrate that long-term use of intraoral jewelry as a component of repeated trauma acts as an accelerant for periodontal attachment loss.8

Another notable possibility of diminished systemic resistance can be associated with lifestyle choices. Necrotizing periodontal disease is an opportunistic infection frequently associated with poor diet, inadequate sleep, smoking, and general debilitation.9 Most often diagnosed in young adults living in stressful environments, it also occurs in immunocompromised individuals. Necrotizing periodontal disease produces rapid alveolar bone destruction and scarring, somewhat reminiscent of this case. It is the authors’ belief that the long-term use of the tongue and lip jewelry was the most likely etiology explaining the severity of periodontal destruction observed in this patient.

Dentists and physicians have an ethical mandate to educate patients about potential complications resulting from intraoral jewelry use. While short-term case reports have documented numerous dental injuries related to intraoral piercing, this long-term case report illustrates the potential for such devices to result in rapid periodontal destruction, tooth loss, and eventually loss of normal function.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Arthur Vernino, DDS, and Jonathan Gray, DDS, for their years of service at the University of Florida and their leadership and loyalty to the profession of periodontics.

References

1. O’Dwyer JJ, Holmes A. Gingival recession due to trauma caused by lower lip stud. Br Dent J. 2002;192:615-616.

2. Chen M, Scully C. Tongue piercing: A new fad in body art. Br Dent J. 1992;172:87.

3. Shacham R, Zaguri A, Librus HZ, et al. Tongue piercing and its adverse effects. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:274-276.

4. Farah CS, Harmon DM. Tongue piercing: case report and review of current practice. Aust Dent J. 1998;43:387-389.

5. American Dental Association. ADA Statement on Intraoral/Perioral Piercing. Available at: http://www.ada.org/prof/resources/positions/statements/piercing.asp. Accessed November 21, 2005.

6. Ranalli DN, Rye LA. Oral health issues for women athletes. Dent Clin North Am. 2001;45:523-538.

7. Campbell A, Moore A, Williams E, et al. Tongue piercing: Impact of time and barbell stem length on lingual gingival recession and tooth chipping. J Periodontol. 2002;73:289-297.

8. Lindhe J, Nyman S, Ericsson I. Trauma from occlusion. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard;2003:352-364.

9. Horning G, Cohen ME. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, periodontitis and stomatitis: Clinical staging and predisposing factors. J Periodontol. 1995;66:990-988.

About the Authors

Gaston Berenguer, DMD, MS, Clinical Assistant Professor, Private Practice, Stuart, Florida and Port St. Lucy, Florida

Andrew Forrest, DMD, MS, Clincial Assistant Professor, Private Practice, Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Gregory M Horning, DDS, MS, Professor and Graduate Program Director

Herbert J Towle, DDS, Professor and Department Chair

Katherine Karpinia, DMD, MS, Associate Professor, Department of Periodontology, College of Dentistry, University of Florida Health Science Center, Gainesville, Florida.