You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Numerous clinical problems (eg, bad posture, malocclusion, and bruxism) involve the masticatory musculature and the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and its related structures, suggesting a typical onset of temporomandibular disorder (TMD). TMD signs and symptoms include sensitization of the head, neck, and masticatory muscles, pain in 1 or both TMJs, limited mandible movements, articular noises, facial deformities, and headaches, which are often present in this clinical onset.1-3

It has been established by some authors that TMD has many causes. Factors such as muscular imbalance, TMJ dysfunctions, occlusal parafunctions, and postural alterations are usually observed in the literature.4-6

The resting position of the mandible is the result of specific coordination between posterior cervical muscles and anterior cervical spine muscles, which are used in inhalation, mastication, swallowing, and speaking. Because the mandible is located within these muscle groups, its resting position depends on the muscular balance.7

The masticatory system, which includes the maxilla, mandible, teeth, TMJs, and all the associated muscles, is directly related to the cervical spine. The neuromuscular influences of the cervical regions and of mastication are actively associated with mandibular movement and cervical posture. Mandibular movement is dictated by neuromuscular control of the masticatory muscles until the initial contact of the teeth.8,9

Occlusion is defined as the relationship between the upper and the lower teeth in functional contact during mandibular activity.10 This contact relationship is classified by Angle’s class of malocclusion system and is based on the anteroposterior relationship between maxilla and mandible The theory is that the first permanent upper molar is invariably in the correct position, composing a more traditional and practical classification.11

TMJ alterations and other associated pathologies are some of the causes of craniomandibular disorders. Among these disorders, craniofacial dysmorphism exists in different occlusal classes in which the position of the mandible has a direct relationship with the posture of the head and shoulders because the mandible consists of an independent bone.12

Literature suggests that occlusal abnormalities are possible causes of headaches, TMDs, and facial pain. However, the influence of the cervical spine in the masticatory structures is often. 9 Severe craniocervical disorders, such as the anteriorization of the head, flattening of the cervical lordosis, and shoulder asymmetry have been recognized in TMD patients.13

Bruxism is the nonfunctional lower teeth grinding against the upper teeth, which may lead to occlusal surface wearing or teeth hypermobility when done in excess, causing TMJ alterations.14 This parafunctional habit is the most destructive among all masticatory system disorders, occurring in 90% of the population with any type of parafunctional habit or TMD sign/symptom.15 The incidence of bruxism is high from ages 10 to 40 but decreases as the ages increase. Although most people present signs of teeth grinding or clenching, only 5% to 20% are conscious of it.

The purpose of this study was to assess head and neck posture in the resting position of individuals with bruxism and in individuals with no TMD signs or symptoms and to relate them to Angle’s classes of malocclusion.

Materials and Methods

Two hundred individuals were randomly selected (students of the University of Mogi das Cruzes, Mogi das Cruzes, São Paulo, Brazil) for this study and answered a questionnaire developed by Fonseca regarding signs and symptoms related to TMD.16 Fifty-six participants, men and women ages 18 to 27, were then selected for the final sample. Individuals who were undergoing physiotherapeutic or dental treatment at the time of the interview or presented with a history of systemic diseases (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, TMJ, or facial traumas) were excluded from the study.

The 56 participants were then divided into 2 groups of 28. Group B (4 men, 24 women) presented with teeth clenching or bruxism according to the questionnaire specifications. Group C (6 men, 22 women) presented with no signs of teeth clenching or bruxism. Group C was treated as the control. These 2 groups were then subdivided into classes I, II, and III according to Angle’s classification of malocclusion.17 The classification was performed by a dentist, who assessed each participant and recorded his or her occlusal classification for further comparison and analysis.

The materials used in this study were a Cyber-Shot DSC-P30 (Sony Electronics Inc, San Diego, CA), a height-adjustable tripod, Alcimagem software, articular markers, computer AMD-K6/2, 500 MHz, and the selective questionnaire.16

The posture of the head and neck was assessed with the Alcimagem software, which offers a quantitive analysis of the images regarding the angles and predetermined marked points. The photographs were taken with the participants standing up (lateral view) and positioned on a predetermined marked position on the floor. The camera was positioned on the tripod, 1.5 meters away from the participant, with adjustable height and zoom. The men were completely undressed in the upper body, and the women wore a bikini top to ensure the points to be analyzed would be clearly visible.

The points analyzed in the software were the manubrium of the sternum, mental protuberance, and spine process of the 7th cervical vertebra (Figure 1). The established angle for analysis from these 3 reference points was the mental protuberance, in agreement with Bara´una, in which variations were observed according to the head posture in the resting position.18 For greater confidence on the collected angles, the average of 3 measurements was used for each person.

Confidence interval was set at 95%, so the confidence interval around the mean of the distribution of means was calculated as: 95% CI = M – (1.96 x SE) to M + (1.96 x SE).

Results

Figures 2 and 3 show the angular values among the subjects from each group and that the variation of these angular values did not present a statistical difference. However, there was greater variation among the angular values presented by Group B (Figure 3).

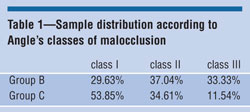

The relationship between Groups B and C and their specific Angle’s class of malocclusion can be observed in Table 1. In Group C, class subjects were the majority (53.85%), followed by class II (34.61%), and class III (11.54%). Group B demonstrated greater division among the classes observed. More participants from Group B were classified as class II (37.04%) and class III (33.33%) than as class I (29.63%).

Discussion

As stated in the literature, it is not possible to recognize an exclusive etiological TMD triggering factor, which originates from an association of psychological, structural, and postural factors and causes unbalance in the dental occlusion, masticatory muscles, and the TMJ.5

The head and neck postural alterations were concentrated in Group B along with a greater number of subjects with classes II and III occlusion. This finding is supported by the literature,8,9 which reports that neuromuscular influences from cervical regions and from mastication act in the movement of the mandible and in cervical positioning.

The study presented by Molina supports that poor cervical spine positioning directly influences the individual’s head, affecting the relationship between the maxilla and the mandible.19 This evidence agrees with the data presented in this study and in the literature, which show that the masticatory system and body position are intimately related.20 An alteration in the head position caused by the cervical musculature directly changes the mandible position, influencing occlusion and masticatory muscles and leading to an alteration in the TMJ.8,21

Most of the data collected from Group C presented Angle’s class I, normocclusion,17 but in Group B, there was a higher prevalence of subjects with malocclusion (classes II and III). This indicates that malocclusion (classes II and III) is associated with TMD, which is supported by Gadotti. The author reported a higher prevalence of normal posture in individuals with class I occlusion.22

The class II occlusion found in Group B was not only more frequent, but it was also demonstrated in posture by an anteriorization of the head. This data is confirmed by the literature,8,10,23 which presents an association between anteriorization of the head in subjects with class II occlusion.

When comparing the data obtained between the groups, a significant difference in the head and neck angles is not displayed; however, individual analysis of each group reveals a variation in the subjects’ angular values and in the occlusal classes. Variations occurred more in the subjects with bruxism (Group B) than in the control group (Group C). This data presented can be supported by the literature. TMJ alterations are associated with craniomandibular disorders, which may be a cause of different occlusal classes, where the mandible position establishes a direct relationship nwith the head and shoulder posture.12

Conclusion

When comparing the mental-sternum angle of the subjects with bruxism and of the subjects without TMD signs or symptoms, a greater variation between the smaller angle and the greater angle was observed in subjects with bruxism.

Angle’s occlusal class I, considered normocclusion, was predominant in the control group; while Angle’s occlusal classes II and III, considered malocclusion, were predominant in the group presenting bruxism, with predominance of occlusal class type II.

References

1. Barclay P, Hollender LG, Maravilla KR, et al. Comparison of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging diagnoses in patients with disk displacement in the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:37-43.

2. Conti PC. Patologias oclusais e disfunções crâniomandibulares: considerações relacionadas a prótese fixa e reabilitação oral. In: Prótese fixa, Pegoraro LF et al. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 1999:23-41.

3. Fernandes Neto AJ. Roteiro de estudo para iniciantes em oclusão. Uberlândia; 2002:151.

4. De Wijer A. Distúrbios temporomandibulares e da região cervical. São Paulo: Editora Santos; 1998.

5. Silva FA. Tratamento das alterações funcionais do sistema estomatognático. Revista APCD. 1993;47:1055-1062.

6. Steenks MH, De Wijer A. Disfunções da articulação temporomandibular do ponto de vista da fisioterapia e da odontologia. São Paulo: Editora Santos; 1996.

7. Darling DW, Kraus S, Glasheen-Wray MB. Relationship of head posture and the rest position of the mandible. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;52:111-115.

8. Biasotto-Gonzalez DA. Abordagem Interdisciplinar das Disfunções Temporomandibulares. 1ª ed. São Paulo: Manole; 2005.

9. Goldstein DF, Kraus SL, Williams WB, et al. Influence of cervical posture on mandibular movement. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;52:421-426.

10. Okeson JP. Fundamentos de oclusão e desordens temporomandibulares. 2a Edição. São Paulo: Artes Medicas; 1992.

11. Moyers RE. Ortodontia. 4a Edição. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 1991.

12. Bricot B. Posturologia. São Paulo: Ícone Editora; 2001.

13. Zonnenberg AJ, Van Maanen CJ, Oostendorp RA, et al. Body posture photographs as a diagnostic aid for musculoskeletal disorders related to temporomandibular disorders (TMD). Cranio. 1996;14:225-232.

14. Dawson PE. Avaliação, diagnostico e tratamento dos problemas oclusais. 2a Edição. São Paulo: Editora Artes Medicas; 1993.

15. Attanasio R. An overview of bruxism and its management. Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41:229-241.

16. Fonseca DM. Disfunção craniomandibular (DCM) – Diagnóstico pela anamnese. Dissertação (Mestrado). FOB/USP, Bauru, 1992.

17. Angle EH. Classification of Malocclusion. Dental Cosmos. 1899;41:248-264.

18. Baraúna MA. Biofotogrametria – recurso diagnóstico do fisioterapeuta. Rev O Coffito. 2002;17:7-11.

19. Molina OF. Fisiopatologia Craniomandibular. Oclusão e ATM. São Paulo: Pancast, 1989.

20. Michelotti A, Manzo P, Farella M, et al. Occlusion and posture: is there evidence of correlation? Minerva Stomatol. 1999;48:525-534.

21. Hertling D, Kessler RM. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders Physical Therapy – Principles and Methods. New York: Lippincott, 1996.

22. Gadotti IC. Analise postural e eletromiográfica (EMG) em indivíduos portadores de classes oclusais de Angle e suas relações com os hábitos parafuncionais. São Carlos, 2003. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Faculdade de Fisioterapia. Universidade de São Carlos.

23. Nobili A, Adversi R. Relationship between posture and occlusion: a clinical and experimental investigation. Cranio. 1996;14:274-285.

About the Authors

Guilherme Manna Cesar, BS, Student, Department of Physical Therapy, Univeristy of Mogi das Cruzes, São Paulo, Brazil

Juliana de Paiva Tosato, BS, Graduate student, Piracicaba Dental School (FOP/UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil

Daniela Ap Biasotto-Gonzalez, DDS, MSc, PhD, Professor, Health Science Physical Therapy Department, University Center 9, São Paulo, Brazil