You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition which develops in individuals who have experienced a life-threatening event such as military combat, a natural disaster, car accidents, or sexual assault.1 The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) has reported the prevalence of PTSD in adults in the United States (US) ranges from 6.8% to 8%.2 In addition, PTSD is most commonly diagnosed in military personnel who have been deployed to a combat zone, with the percentage of veterans with PTSD reported at about 12%, greater than the general population.1,3 Despite the prevalence of PTSD in the US population, a

review of the literature revealed a paucity of research has been conducted regarding the knowledge level of oral health providers and the management of patients who present with this condition. Research conducted in the field of dentistry has been limited to investigations into the relationship of PTSD to temporomandibular disorder (TMD) and dental anxiety4-11 but has not explored the preparation of oral health care providers in caring for patients suffering from PTSD.

Regardless of the event which may have initiated PTSD, research has revealed both children and adults diagnosed with the condition are more likely to present with poor oral health (OH).4-6 They are also at increased risk for TMD, defined as any pain or dysfunction involving the muscles of mastication and the temporomandibular joint.7,8 In addition to the oral manifestations found to be associated with PTSD,4,7-9 a relationship between PTSD and dental anxiety has been identified.10,11 Researchers who have investigated the relationship between PTSD and dental anxiety have suggested oral health care providers need to develop a heightened awareness of the association between the two conditions, in order to appropriately alter their approach to caring for these patients.10,11

Interventions to assist patients with PTSD, which might allow providers to more successfully deliver care to patients suffering from this condition include: use of nitrous oxide, relaxation therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, group therapy, and computer-assisted relaxation learning (CARL), a desensitization program aimed at reducing dental fear.12 Other techniques have been implemented to assist in delivering patient care; pre-treatment anxiety questionnaires, extended appointment time, distraction techniques, and psychotherapy techniques such as flooding and implosion, which are approaches used to stimulate and focus on the patient's specific fear which can elicit repressed emotions.12 Despite the success of these interventions, not all techniques are available to dental hygienists (DHs) in the clinical practice setting.11,12 Many clinicians may be unaware of the techniques and their benefit to patients with PTSD.11,12

The purpose of this study was to assess the level of education DHs had received regarding caring for patients with PTSD, their understanding of the patients' increased risk for dental anxiety and TMD, and the approaches or treatment modifications taken when treating patients with PTSD.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was deemed exempt by the MCPHS University Institutional Review Board. Convenience and purposive sampling were used to recruit DHs currently practicing clinically in the US. Participants were recruited via invitations posted on multiple dental hygiene social media sites and directed to the electronic survey (Survey Monkey; San Mateo, CA, USA) by way of a link posted on the site. The social media sites used to recruit participants included Dental Hygiene Network, RDH, Dental Hygiene Life with Andy RDH, Dental Hygienist Talk, Boston Dental Peeps, RDH Network, and Dental Hygienists Network. Inclusion criteria for study participants were DHs who had been actively practicing for at least 6 months; retired or currently practicing DHs were excluded from participating.

Implied consent was secured through an informed consent statement at the beginning of the survey. Completion of the survey acknowledged consent to participate. A power analysis using a medium effect size w=.3, α=.05, and 80% power was performed. Adjusting for a 30% attrition rate, the final recommended sample size was n=229.

A modified version of a dental anxiety survey developed by Drown et al.13 was selected because of the similar nature of the Drown et al.13 study to the current study design. The Drown et al.13 instrument was modified with permission and the term PTSD replaced the term dental anxiety. The 22-item instrument included 13 questions assessing participants' knowledge, practices for patients with PTSD and their risk for dental anxiety and TMD. Responses were a combination of two binary items, six 7-point Likert scale items, three multiple answer items, one single answer item, and one open-ended question. The nine demographic questions included gender, age, years of practice, education level, number of days and hours worked each week, total number of adult patients treated each week and number of patients identifying as having PTSD.

Prior to dissemination, the survey was piloted with DHs (n=5) who met the inclusion criteria. Feedback from the pilot study participants revealed there were no issues with accessing and completing the survey, and the participant recruitment was initiated. The survey remained open for three weeks, with data collected directly from the survey website. Descriptive statistics were used to report the findings using a statistical software program (SPSS 26; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Spearman's Rho test was used to analyze the ranked data to identify any correlations between the demographic data and participants' responses to each of the survey questions.

Results

A total of 362 participants opened the survey (n=362) for a 94% completion rate (n=342). The mean age of the respondents was 41.15 years (SD=12.36), and they had been in dental hygiene practice for 15.42 years (SD= 12.17) and estimated that 15.07% (SD= 17.91) of their patients suffered from some form of PTSD. Participant demographics are shown in Table I.

Most participants (58.2%, n=192) reported that they had not received any curricular content related to PTSD from lectures or textbooks during their dental hygiene education. In addition, nearly half (47.8%, n=163) reported they had not received any preparation for treating patients with PTSD during their undergraduate education. A small number of participants (11.1%, n=38) indicated having completed continuing education or training regarding treatment of patients with PTSD since completing their dental hygiene education program (Table II).

Some participants (16.5%, n=56) reported having a question about PTSD in their patient health history, while over one third (39.1%, n=132) were uncertain whether their dental practice treated patients with PTSD. Despite the lack of formal training in managing patients with PTSD, most participants (55.0%, n=188) felt confident in their ability to treat these patients. Responses were mixed regarding the disruptive nature of caring for a patient with PTSD with 44% (n=147) reporting that it was not disruptive and 39.8% (n=133) reporting that it was significantly disruptive. Most participants recognized dental patients with PTSD were at a significantly high risk for dental anxiety (77.3%, n=260) and for developing TMD symptoms (61.4%, n=207). Participant experiences and perceptions of patients with PTSD are shown in Table II.

Although the participants' responses reflected an understanding of the link between dental anxiety and TMD and PTSD, most (68.7%, n=235) did not employ any interventions to address the condition during oral health care appointments. Participants who did employ specific approaches most commonly used distraction (38.9%, n=133) or added an additional appointment (37.4%, n=128). Flooding/implosion and CARL (0.29%, n=1) respectively, were reported approaches but used infrequently (0.29%, n=1). Treatment interventions for patients with PTSD are shown in Table III. The most frequently identified barrier to providing interventions was a lack of awareness of successful interventions (50.6%, n=173), followed by implementation of the interventions being too time consuming (15.5%, n=53) (Table IV).

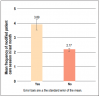

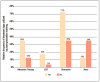

A Spearman's Rho analysis of the ranked data revealed the level of PTSD education and training significantly impacted the mean frequency in modifying delivery of care during patient care sessions; those who received training were more likely to modify treatment (μ=3.89) as compared to those who had not received training (μ=2.17) (Figure 1). However, no statistically significant difference was found between the confidence level of participants who had received PTSD training (μ=5.74) and those who had not received training (μ=4.35) (Figure 2). Frequency in using interventions was positively correlated with receiving post-graduate training in PTSD and employing patient treatment modifications (Figure 3). Participants who reported receiving PTSD education were more likely to use interventions during treatment than those who had not received training. Distraction was the most frequently identified intervention used in treating patients with PTSD (38.9%, n=133), with participants who had received PTSD education (μ=5.74) using this approach more frequently than participants who had not received training (μ=4.35) (Figure 3).

Discussion

Although most of the DHs in this study had not received any PTSD education during their undergraduate education or post-graduation, most participants recognized that patients with PTSD were at moderate to high risk for dental anxiety and for developing TMD. This reported lack of PTSD education might have suggested that DHs had insufficient knowledge regarding the condition and its implications for oral health. However, the participants were provided a definition of PTSD at the beginning of the survey, and this may have given sufficient information to assist the participants in responding to the questions related to the risks associated with PTSD.

Despite the participants' ability to recognize the risk for dental anxiety and TMD in patients with PTSD, and a self-reported high level of confidence in treating patients with PTSD, the study results demonstrated DH's lack of knowledge on how to manage patients with PTSD. A significant finding in the study was the correlation found between the lack of PTSD education and training, and the frequency interventions were used in managing patients with PTSD. Participants with previous education related to caring for patients with PTSD were more likely to employ treatment strategies while providing dental hygiene care. Lack of knowledge regarding effective treatment methods was identified as the greatest barrier to employing specific care interventions. The minimal use of interventions and lack of PTSD education revealed in this research support the findings of Hoyvik et al. that suggested dental providers need to have greater awareness when assessing patients with PTSD and managing their patient care sessions.11

Interventions most frequently employed by participants were distraction, and the extension of appointment time. These approaches may have been chosen due to the lack of advanced training required for these interventions. A self-directed computer-based series for coping strategies, CARL, was another intervention identified by participants that did not require specialized training. The use of CARL in dentistry has been investigated previously in research by Heaton et al., which found CARL effectively reduced patients' dental phobia and fear of dental injections.12 Computer-based relaxation therapy and virtual reality systems have been adopted previously by the US military as an intervention for soldiers dealing with anxiety, stress and PTSD.14 Integrating this technology as a method of PTSD treatment has been found to be effective, and has allowed for delivery of therapy independent of direct care from a clinician.14 Using technology for delivery of behavior health treatment could be an option for DHs seeking interventions without need of specialized training. Its ease of use, and the patients' perception that treatment delivery is occurring in a more welcoming environment, may make this a viable option for DHs.14

Although participants reported the successful use of PTSD treatment interventions which did not requiring specialized training, the development of community-based programs offering specialized training for health care providers has been recommended.15 Opportunities for health care providers to access training in the use of evidence-based treatment (EBT) interventions for patients with PTSD has been limited and offered primarily to mental health providers.15 Expanding access to EBT interventions to health care providers on a national level could expand the current toolkit available to DHs and other health care providers in the treatment of patients with PTSD.15

This study had limitations. The non-probability, social media sampling method and the small sample size limit the generalizability of the results. Participants with a higher level of interest or knowledge in PTSD may have self-selected to participate. Also, the survey relied on self-reported data and there may have been recall bias. Further research with a larger sample is warranted. Future studies should also investigate the level of education regarding PTSD being offered to dental hygiene students during undergraduate education.

Conclusion

Dental hygienists who had received education on caring for patients with PTSD were more likely to use interventions during the provision of dental hygiene care. Results suggest that education on PTSD and its impact on oral health should be incorporated into the dental hygiene curriculum to better prepare graduates to care for this patient population. Continuing education courses and training programs should be developed to focus on the special needs of patients suffering from PTSD, allowing oral health care providers to better recognize risk factors for the condition, develop effective protocols for treatment modifications, and improve oral health outcomes for these patients.

Chelsea B. Simone, RDH, MS is a graduate of the MCPHS University Master of Science in Dental Hygiene Program; Dianne L. Smallidge, RDH, EdD is a professor and the Interim Dean of the Dental Hygiene Program; Lory Libby, RDH, MS is an assistant professor; Jared Vineyard, PhD is a member of the adjunct faculty, all at the Forsyth School of Dental Hygiene, MCPHS University, Boston, MA, USA.

References

1. Veterans Administration. Understand PTSD [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs: 2021 [updated 2019 Feb 15; cited 2021 Jan 24]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/index.asp

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Post-traumatic stress disorder [Internet]. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 2021 [updated 2019 May; cited 2021 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml

3. Ainspan N, Bryan C, Penk WE. Handbook of psychosocial interventions for veterans and service members: a guide for the non-military mental health clinician. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2016 Jun. 488 p

4. Muhvić-Urek M, Uhač I, VukšIć-Mihaljević ž, et al. Oral health status in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Oral Rehabil 2007 Jan;34(1):1-8.

5. Hamid SH, Dashash MA. The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on dental and gingival status of children during Syrian crisis: a preliminary study. J Investig Clin Dent 2019 Feb;10 (1) e12372.

6. Tagger-Green N, Nemcovsky C, Gadoth N, et al. Oral and dental considerations of combat-induced PTSD; a descriptive study. Quintessence Int. 2020; 51(8): 678-85.

7. De Oliveira Solis AC, Araújo ÁC, Corchs F, et al. Impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on oral health. J Affect Disord. 2017 Sep; (219): 126-32.

8. Cyders MA, Burris JL, Carlson CR. Disaggregating the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters and chronic orofacial pain: implications for the prediction of health outcomes with PTSD symptom clusters. Ann Behav Med 2011 Feb; 41(1), 1-12.

9. De Leeuw R, Bertoli E, Schmidt JE, Carlson CR. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in orofacial pain patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005 May; 99(5): 558-68.

10. Hoyvik AC, Lie B, Willumsen T. Dental anxiety in relation to torture experiences and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Eur J Oral Sci. 2019 Feb; 127: 65-71.

11. Jongh AD, van Eeden A, van Houten CM, van Wijk AJ. Do traumatic events have more impact on the development of dental anxiety than negative, non-traumatic events? Eur J Oral Sci. 2017 Jun; 125: 202-7.

12. Heaton LJ, Leroux BG, Ruff, PA, Coldwell SE. Computerized dental injection fear treatment. J Dent Res. 2013 Jul; 92 (7 Suppl): S37-S42

13. Drown DA, Giblin-Scanlon LJ, Vineyard J, et al. Dental hygienists' knowledge, attitudes, and practice for patients with dental anxiety. J Dent Hyg. 2018 Jul; 92(4):35-42.

14. Stettz MC, Folen RA, Yamanuha, BK. Technology complementing military behavioral health efforts at Tripler Army Medical Center. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011 Jun; 18:188-195

15. Dondanville K, et al. Launching a competency-based training program in evidence-based treatments for PTSD: supporting veteran-serving mental health providers in Texas. Community Ment. Health J. 2021 July; 57(5):910-19.