You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Introduction

More than a year and a half into the pandemic, COVID-19 continues to fill hospital beds and disrupt the United States (US) health care system. As of late October 2021, there have been more than 45 million reported cases in the US and more than 740,000 deaths.1 Only 63.2% of the U.S. population is fully vaccinated,1 and COVID-19 variants prevents the "return to normal" and poses risks to all sectors of the population, including children.2 Despite these setbacks, the US dental care system has shown positive signs of recovery. As of the week of October 11, 2021, nearly all dental practices are open and average patient volume has been reported to be 90% of pre-COVID levels.3 Supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) are no longer as big of an obstacle for employers as they were in early 2020, and fewer dentists reported the need to take additional measures such as borrowing money from a bank to maintain financial stability.3 However, a recurring issue reported by dentists is the inability to hire dental practice staff, particularly dental hygienists. Nearly one-third (31.7%) of surveyed dentists are actively recruiting dental hygienists, and 90% of those dentists said recruiting dental hygienists is extremely or very challenging compared to before the pandemic.3

In a previous study of employment patterns of dental hygienists during the pandemic, it was noted that the majority of surveyed dental hygienists who were unemployed in October 2020 left the workforce voluntarily, primarily due to concerns about workplace safety as well as the ability to find childcare.4 A study of dental hygiene employment conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 found that 43% of dental hygienists indicated the primary reasons for seeking a new job in the coming year included not feeling valued or respected and finding their current compensation unacceptable.5 The effects of COVID-19 compounded these sentiments in that employees were unhappy about being required to use paid vacation time and sick time to cover the office shutdowns; and once they returned to work, they faced longer hours, more rigorous safety protocols, and more hand scaling in order to reduce aerosols.5 Studies continue to indicate that the pandemic has had a more significant economic impact on women.6,7 Female-dominated professions, including dental hygiene, are bound to see setbacks in employment recovery.

Since September 2020, the American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) and the American Dental Association's Health Policy Institute (HPI) have tracked employment pattern data among dental hygienists.4,8 Continued research is needed to identify ways to support dental hygienists who may be reluctant to rejoin the workforce and for dentists and policymakers to better understand the challenges that remain in hiring of dental practice personnel. The purpose of this study was to update previous research on dental hygienists' employment patterns and reasons for exiting the workforce during the pandemic.

Methods

A total of twelve anonymous, web-based surveys (Qualtrics; Provo, UT, USA) were administered between September 2020 and August 2021, with gaps ranging from four to six weeks between waves of data collection. Licensed dental hygienists in the American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) database (n=133,000) were invited to participate in the study if they were at least 18 years old and had been employed as a dental hygienist as of March 1, 2020, prior to the closure of dental practices in the US due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants gave written informed consent before the survey, and there was no incentive given to respondents for participating. The survey was sent monthly and remained open for 5-10 days for responses. Further details of the study population and questionnaires are described in previous publications.4,9

Statistical analysis was conducted in Qualtrics Core XM and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to track respondent employment status and reasons for not currently working. Cross tabulation analysis included employment status and reasons for not working by age group. Due to the complex survey question skip patterns and because respondents were able to skip any non-screening question or stop answering the survey at any time, not all respondents answered all questions.

Results

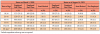

Of the respondents who opened the first survey in September 2020 (n=4,804) approximately 4,300 dental hygienists representing all 50 states, Washington D.C., Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands volunteered to join the panel and receive monthly surveys. In subsequent waves, new participants were recruited to increase the number of respondents and to replace those that dropped out. A total of 19,065 responses were received over the course of the study. Including those who joined the panel after the first wave of the survey, a total of 6,976 eligible dental hygienists agreed to the consent form and participated in at least one wave of the survey. The number of responses received following the baseline survey ranged from 960 to 1,629 per wave. Respondents were primarily female (88.8%, n=6,192), ranged in age from 18 to 77 years of age (mean: 44.4, SD:11.9), and predominantly non-Hispanic white (73.4%, n=5,118). Sample demographic information is highlighted in Table I.

Six months into the pandemic and during the initial wave of the survey, about 8% of the respondents (n=360) who had been employed as of March 1, 2020, indicated that they had left their jobs. In subsequent months of the study, the percentage of respondents who were not employed as dental hygienists dropped to 3.8% (April 2021) and never rose above 5.8%. When the study concluded in August 2021, 4.9% (n=59) of participants were still not employed as dental hygienists (Figure 1).

All age groups experienced shifts in employment status compared to pre-pandemic work, and there was a decline in the percentage working full-time. In March 2020, 68.2% (n=4,600) of the participants were employed in full-time positions. As of August 2021, the number of participants employed full-time fell to 57.6% (n=701), whereas those working part-time (33.1%, n=403) or who were semi-retired (4.4%, n=53) increased compared to pre-COVID-19 levels. Respondents in older age groups were more likely to be working less or not at all in August 2021 compared to March 2020. One in seven dental hygienists over the age of 65 were not employed (14.5%, n=12) and one in four were semi-retired (24.1%, n=20), compared to 2.8% (n=5) not employed and 0% semi-retired, among those under 35 years of age (Table II).

In the baseline survey, most participants (59.1%, n=205) who were currently not working were doing so voluntarily. Over the course of the study, voluntary departures were predominant and increased proportionately over time. As of August 2021, just under three-quarters (74.1%, n=43) of respondents not employed as dental hygienists left their positions voluntarily. The proportion of participants laid off or furloughed by their employers fell from 24.1% (n=84) in September 2020 to 6.9% (n=4) in August 2021, while those permanently let go increased slightly between those same time periods, rising from 16.7% (n=58) to 19.0% (n=11) (Figure 2).

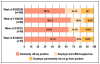

Each month, respondents who were no longer employed in a position as a clinical dental hygienist reported the reasons they had left the workforce. Safety concerns for self and others were the primary reasons for electing not to work. Throughout the course of the study, "I do not want to work as a dental hygienist until after the COVID-19 pandemic is under control" was the response given by at least 30% of respondents; this response peaked during the December 2020 wave of data collection (71.4%, n=25). "I have concerns about my employer's adherence to workplace/safety standards" was reported by 20% to 60% of respondents in each round of the survey. Workplace safety remained the second most important concern reported by participants throughout the study.

In early March 2021, nearly one-third (32.5%, n=13) of the participants choosing not to practice reported that they were waiting to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. By August 2021, 80.5% of the study participants were partially or fully vaccinated.10 Waiting for the vaccine was no longer a significant factor for those voluntarily not employed as dental hygienists, as only 2.3% (n=1) cited this as a reason for not returning to clinical practice (Table III).

During the first several months of data collection, "I have insufficient childcare while working" was reported by about one-quarter of the voluntarily unemployed participants. However, beginning in April 2021, this reason began to decrease in prevalence and was reported to be 11.6% (n=5) at the conclusion of the study.

Early in this research, approximately one in ten participants reported voluntarily not returning to work in the dental practice because they had retired from the profession. Midway through the study in March 2021, one-fourth of the respondents (n=10) cited retirement as the reason for electing not to work in clinical practice. In the final wave of the study (August 2021), 37.2% (n=16) of respondents who were voluntarily no longer employed, indicated that they had retired. More than 80% of the participants who had voluntarily left dental hygiene practice due to retirement were over the age of 55.

Discussion

Study results indicate that the pandemic has resulted in a voluntary contraction of the US dental hygiene workforce by about 3.75%, or approximately 7,500 dental hygienists of the total dental hygiene workforce. In the final wave of the study, 1.6% of the participants indicated that they had either retired or no longer wanted to work clinically as a dental hygienist, which could represent a permanent reduction in the workforce of close to 3,300 dental hygienists.

The American Dental Association's Health Policy Institute (HPI) economic impact of COVID-19 dentist poll has periodically tracked the recruitment of dental hygienists throughout the pandemic.3 In August 2021, 90% of dentists who were actively hiring dental hygienists considered recruitment "extremely" or "very" challenging compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Recommendations for recruiting and retaining dental hygienists from the Academy of General Dentistry and others have included addressing reasons for dissatisfaction including workplace safety and compensation. Additional suggestions for recruitment and retention have included increasing communication and intentionally creating a culture that helps team members feel valued and appreciated such as reviewing compensation and offering retention bonuses, providing transparency, increasing benefits, reviewing dental hygiene production and hiring a dental hygiene assistant.6,11 Effective interviewing, investing in the team, providing the opportunity to take on new responsibilities and create innovation, and adherence to safety protocols following national guidance for a safe operatory were also recommended. 5,11

Results of this study suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a reduction in the dental hygiene workforce, and based on recruitment challenges reported by dental practices, a labor shortage in the short-term. However, a small portion of the participants in this study indicated that they no longer want to be employed as a dental hygienist, even after the COVID-19 pandemic is under control. Findings from this study suggest that non-adherence to CDC infection control guidance and COVID-19 protocols in the workplace is of concern to dental hygienists and contributes to the decision whether to continue to be employed as a dental hygienist. It remains to be seen whether the supply of future dental hygienists will be sufficient in the long-term to replace those who are not returning to the workforce. The number of dental hygienists graduating from accredited dental hygiene programs in the United States from 2013 to 2019, hovered at around 7,300 annually, a number slightly below the estimated labor contraction caused by the pandemic.12 Additionally, first-year enrollment in dental hygiene programs fell by about 7% for the 2020-21 academic year (the first cohort to enroll after the start of the pandemic), which may have a compounding impact on the outlook for the dental hygienist workforce. It is unknown whether this decline in enrollment was due to students selecting other fields of study or whether students were delaying the start of college for a year. Dental hygiene programs may also have reduced their enrollment numbers because of COVID-19 protocols for instruction.

This study is not without limitations. The research is based on self-reported data, which may be influenced by recall or social desirability bias. In addition, the small number of voluntarily unemployed respondents in each survey wave limits the generalizability of the results related to that subgroup. However, confidence in these findings can be strengthened by the large number of study respondents overall (n=6,976) and their representativeness of US dental hygienists. Future research should examine whether the supply of new dental hygiene graduates will be sufficient to maintain workforce levels after the COVID-19 pandemic resolves. Studies should also address whether the recommended efforts to recruit and retain dental hygienists are effective. Examining the employment perspectives of dental hygienists from a qualitative perspective may yield greater understanding of the influencing factors that impact decisions to return to or engage in employment in clinical practice settings.

Conclusion

Results from this study provide the first empirical insight into the impact of COVID-19 on dental hygiene employment in the US. The impact of COVID-19 has led to a reduction in the dental hygiene workforce that is likely to persist at least until the pandemic passes. The labor market for dental hygienists has tightened, with significant recruitment challenges being reported by dentists looking to hire dental hygienists. Results also indicate there will likely to be a much smaller, but longer lasting impact, as some dental hygienists choose to permanently leave the workforce.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. This research was funded by the American Dental Hygienists' Association and the American Dental Association.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all survey participants for generously sharing their thoughts and experiences.

Rachel W. Morrissey, MA is a Senior Research Analyst, Education and Emerging Issues, Health Policy Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

JoAnn R. Gurenlian, RDH, MS, PhD, AFAAOM is the Director of Education & Research, American Dental Hygienists' Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Cameron G. Estrich, MPH, PhD is a Health Research Analyst, Evidence Synthesis and Translation Research, American Dental Association Science & Research Institute, LLC, Chicago, IL, USA.

Laura A. Eldridge, MS is a Research Associate, Evidence Synthesis and Translation Research, American Dental Association Science & Research Institute, LLC, Chicago, IL, USA.

Ann Battrell, MSDH, is the Chief Executive Officer, American Dental Hygienists' Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Ann Lynch is the Director of Advocacy, American Dental Hygienists' Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Matthew Mikkelsen, MA is the Manager, Education Surveys, Health Policy Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Brittany Harrison, MA is the Coordinator, Research and Editing, Health Policy Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Marcelo W. B. Araujo, DDS, MS, PhD is the Chief Science Officer, American Dental Association, Science & Research Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

Marko Vujicic, PhD is the Chief Economist and Vice President, Health Policy Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 data tracker weekly review [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021 Oct 29 [cited 2021 Nov 2]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: state-level data report [Internet]. Itasca (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021 Sep 7 [cited 2021 Sep 13]. Available from:

3. Health Policy Institute. COVID-19 economic impact on dental practices, results for private practice [Internet]. Chicago (IL): American Dental Association; 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 2]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/health-policy-institute/impact-of-covid-19/private-practice-results

4. Gurenlian JR, Morrissey R, Estrich CG, et al. Employment patterns of dental hygienists in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Hyg. 2021 Feb; 95(1):17-24.

5. Lanthier T. Survey: COVID-19 compounds dental staffing challenges [Internet]. Nashville (TN): Endeavor Business Media; 2021 [cited 2021 Oct 11]. Available from https://www.dentaleconomics.com/print/content/14198501

6. Munson B, Vujicic M, Harrison B, Morrissey R. How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect dentist earnings? [Internet]. Chicago (IL): American Dental Association; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/hpi/hpibrief_0921_1.pdf

7. Smith M. Less than 12% of August job gains went to women. [Internet]. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Consumer News and Busines Channel; 2021 Sep 3 [cited 2021 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/03/august-jobs-report-reveals-slowing-economic-recovery-for-women.html

8. Health Policy Institute. COVID-19 economic impact on dental practices. Results for dental hygienists. [Internet]. Chicago (IL): American Dental Association; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/resources/research/health-policy-institute/impact-of-covid-19/dental-hygiene-results

9. Estrich CG, Gurenlian JR, Battrell A, et al. COVID-19 prevalence, and related practices among dental hygienists in the United States. J Dent Hyg. 2021 Feb;95(1):6-16.

10. Gurenlian JR, Eldridge L, Estrich CG, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Intention and Hesitancy of Dental Hygienists in the United States. J Dent Hyg. 2022 Feb; 96(1):5-16.

11. Levin RP. Addressing the dental hygienist shortage [Internet]. Chicago (IL): Academy of General Dentistry; 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 9]. Available from https://www.agd.org/constituent/news/2021/08/09/addressing-the-dental-hygienist-shortage

12. Health Policy Institute. Survey of allied dental education, 2020-21 [Internet]. Chicago (IL): American Dental Association; 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/data-center/dental-education.