You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic of COVID-19, an infection caused by a novel beta coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.1 The virus is primarily transmitted by inhalation or mucus membrane contact with infected respiratory droplets or aerosol particles.2 Gravity causes larger respiratory droplets to fall out of the air over time and distance, while smaller droplets and aerosol particles dilute in the surrounding air. General principles adopted in the United States (US) to prevent a COVID-19 infection include distancing from other individuals (operationalized as 6 feet), wearing masks or other barrier face coverings, and avoiding enclosed shared spaces where exhaled respiratory droplets and aerosol particles can accumulate.2 However, in order to provide oral care, dental hygienists must work in close proximity to patients who are unmasked, creating the potential for higher SARS-CoV-2 transmission risk to dental hygienists. This risk may be increased by various dental procedures that generate droplets and aerosols (AGP),3 or reduced via the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection prevention and control (IPC) practices within the dental practice setting.

During the period of this study (September 2020 through August 2021), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) interim guidance for dental settings included face masks or coverings for everyone in a dental practice setting.4 Dental healthcare workers were advised to continue to adhere to standard precautions, and in the case of an infectious disease diagnosis, transmission-based precautions. During procedures likely to generate splashing or spattering of blood or other body fluids, or AGPs, the CDC recommended dental health care workers wear a surgical mask, eye protection, a gown or protective clothing, and gloves. In areas with moderate community transmission (defined as ≥10 new COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people in the past 7 days),5 the CDC recommended dental health care workers wear eye protection in addition to their surgical mask during all patient care encounters. During AGPs, or when providing oral care to a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, the CDC recommended dental health care workers also wear an N95 respirator or a respirator that offers an equivalent or higher level of protection.4

During AGPs, the CDC also recommended that dental healthcare workers use four-handed dentistry, high evacuation suction, and dental dams to minimize droplet splatter and aerosols.4 In terms of the practice environment, the CDC recommended dental practices use teledentistry instead of in-office care when appropriate, limit non-patient visitors, schedule appointments to minimize the number of people waiting or being treated simultaneously, limit clinical care to one patient at a time when possible, and set up operatories so only the supplies and instruments needed for the dental procedure are readily accessible. Ideally, oral care should be provided in individual patient rooms or operatories. If this is not possible, the patient chairs should be at least 6 feet apart or have physical barriers between them, and where possible, patients' heads should be oriented away from others and toward air vents or rear walls. In reception areas, the CDC recommended practices included posting visual alerts and supplies to encourage hand, respiratory, and cough hygiene, installing physical barriers, regularly cleaning and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces, and removing objects that cannot be regularly cleaned. If possible, patients should be screened for COVID-19 symptoms via telephone or teledentistry before their appointment, and everyone entering the practice setting should also be screened for symptoms. The CDC additionally recommended higher ventilation and air cleaning rates and efficiency and the use of upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation. On a global level, the WHO interim guidance largely coincides with the CDC guidance, although WHO also recommended pre-procedural rinsing with 1% hydrogen peroxide or 0.2% povidone iodine.6

Research on dental hygienists' PPE and IPC is limited and largely conducted outside of the US. A web-based survey was administered to Italian dental hygienists in May 2020 (n=2,798), and found that in regards to ICP procedures: 64.6% triaged patients via telephone, 58.8% delayed appointments to reduce the number of patients waiting together, 65.9% verified patients' health status before treatment, 66.9% disinfected frequently touched surfaces, 77.4% frequently ventilated the waiting rooms, and 74.1% removed or disinfected all devices.7 Compared to Italian dentists (n= 3,599),8 a higher proportion of dental hygienists wore surgical masks (82.8%), but a lower proportion wore FFP2/FFP3 respirators (29.8%). An international survey of dental hygienists also conducted in May 2020 found that 69% of the respondents indicated wearing surgical masks to treat patients, 46% wore N95 respirators, and 76% also used face shields.9 Regarding ICP practices, 71% screened patients for symptoms by telephone, 81% screened patients for symptoms before treatment, 68% limited patient contact within waiting rooms, 10% used negative air pressure air filtration, and 85% cleaned or disinfected all surfaces in the operatory between treatments.9 Pre-procedural rinses were required of patients in practices of 57% of the surveyed dental hygienists; the most common rinse was hydrogen peroxide, used by 73% of the respondents.9

The infection prevention and control practices of dental hygienists in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported previously.10 As the SARS-CoV-2 virus continues to mutate and the COVID-19 pandemic remains a global health crisis, it is important to continue to monitor the IPC and PPE practices of dental hygienists as front-line, essential oral health care providers. The purpose of this longitudinal study was to continue to explore the IPC and PPE trends and predictive factors of dental hygienists in the US.

Methods

A web-based survey designed by the American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) and the American Dental Association (ADA) was administered via Qualtrics Core XM (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) from September 2020 through August 2021. Email invitations to participate in the anonymous survey were sent to all licensed dental hygienists in the US and its territories from the ADHA database (n=133,000). Dental hygienists were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years old, licensed to practice in the US or in one of its territories, and had been employed as a dental hygienist as of March 1, 2020. Membership in the ADHA was not required for participation. Respondents gave informed consent prior to starting the survey; there were no participation incentives.

Following recommendations by Riley et al.,11 the sample size required for predictive multivariable logistic regression analysis in order to fulfill the study's primary aim of estimating COVID-19 risk was calculated to be n=2,059, based on assumptions that: prevalence of COVID-19 = 1.5%,9 R2 = 0.05, covariates=8, shrinkage=0.9, and that 68% of first wave survey respondents would continue to answer surveys over time.12

Surveys were emailed between 4-6 weeks apart. Participants could leave or join the study at any time and could skip any question. The surveys and study protocols were approved by the ADA Institutional Review Board and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04423770).

Survey Instrument

Each participant received a baseline survey that collected demographics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, zip code, medical history and comorbidities related to COVID-19, and dental practice characteristics. Details of the baseline survey have been described in previous publications.10,13 In the survey administered in September 2020, respondents were asked to select all the types of PPE worn when treating patients. In subsequent surveys this question was divided into two separate items; one for dental procedures that do not generate aerosols, and another for procedures likely to generate aerosols. Each survey included items on the supply of PPE, frequency of reuse of masks or respirators, and IPCs. IPCs were based on the CDC and ADA and ADHA interim guidance for dental practice settings and included a list of 11 categories4,14; respondents were asked to select which if any were in place in their primary dental practice. Additional items relating to COVID-19 vaccination and testing were added to the survey in January 2021; quantity of AGPs and the use of a fit-tested N95 or equivalent respirator during AGPs was added in May 2021; infection control procedures relevant to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Emergency Temporary Standard (ETS) that was issued June 202115 were added in July and August of 2021.

Data Analysis

Community level of transmission of COVID-19 was defined by the COVID-19 case rate per 100,000 people in each US state and territory for the 7 days before each survey. It was categorized according to the CDC's criteria as low if <10 new cases per 100,000 and moderate or higher if ≥10 new cases per 100,000.5 Respondents in areas with low community transmission were considered to have been wearing PPE according to CDC recommendations if they reported always wearing a surgical mask, eye protection, a gown or protective clothing, and gloves when treating patients. Respondents in areas with moderate or higher levels of community transmission were considered to have been wearing PPE according to CDC recommendations if they reported always wearing a surgical mask, eye protection, a gown or protective clothing, and gloves when treating patients during non-AGPs, and if during AGPs they always wore an N95 respirator or respirator offering an equivalent of higher level of protection. Since it was not possible to know which PPE respondents used during AGPs compared to non-AGPs in the September 2020 survey, PPE use during AGP for that survey was reported but not statistically compared to subsequent months. The use of PPE during patient care and the implementation of IPCs in the dental practice setting over the past month were calculated for respondents who had practiced during that month.

Statistical significance was set at 0.05. To adjust for multiple responses over time from the same individuals, descriptive statistics were conducted in Stata 17.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) using xt commands; multilevel multivariable logistic regression was used. Linear regression modeling for trends in time and tests for changes in trends were conducted in Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.9.0.0 (Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, USA). Write-in responses were qualitatively analyzed using content analysis in Qualtrics independently by two researchers.

Results

Personal and professional characteristics

At the conclusion of the study period in August 2021, a total of 7,004 dental hygienists had responded to the survey and most provided informed consent to participate (99.6%, n=6,976). The first survey (September 2020) had the largest sample size (n=4,776), and 42.3% of those respondents (n=1,828) continued to respond to further surveys. Nearly half of the sample (47.3%, n= 3,299) responded to two or more surveys. Only a small number responded to all twelve surveys (1.3%, n=92). Respondents were most commonly non-Hispanic White (73.4%, n=5,118), female (88.8%, n=6,192), and ranged in age from 18 to 77 years (mean: 44.4 years, SD: 11.9). Respondents' demographics are described elsewhere in more detail.16

In each of the months surveyed, between 3.8% to 7.9% of the respondents were not currently employed as a dental hygienist.16 On average, over three fourths of the respondents (78.5%) had provided dental care during the previous month, ranging from a low of 70.3% in September 2020 to a high of 83.2% in December 2020. Aerosol-generating procedures were common throughout the survey period. Most of the respondents had performed or were in the room during AGPs during the previous month at the time of the September 2020 survey (90.7% (n=3,037); a proportion that steadily rose to 97.1% (n=941) at the time of the last survey in August 2021.

Participants were asked in the May 2021 survey how the current level of AGPs that they had performed in the past month compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic. One third reported performing fewer AGPs (34.2%, n=351), however a small number (7.7%, n=79) reported performing more AGPs than before the pandemic. About half (58.1%, n=596) performed the same number of AGPs as previously. Another noteworthy finding was that over the course of the survey, 0.9% of the respondents (n=62) reported the primary reason they voluntarily stopped working as a dental hygienist was due to concerns regarding safety standards in their place of employment.

Infection prevention and control practices

Almost all practicing dental hygienists (99.9%, 14,926 observations) reported there were COVID-19 specific infection prevention control practices in place at their primary dental practice. On average, they selected a total of 8 (SD: 1.78) of the 11 different categories of IPC. Most common categories included disinfecting equipment in the operatory between patients (99.4%), staff masking (99.1%), screening patients for COVID-19 symptoms and exposure (97.4%) and disinfecting frequently touched surfaces (94.2%). Only 0.4% of the respondents indicated that there were no IPC protocols in their primary dental practice in response to COVID-19.

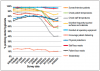

Each month, >96% of respondents reported disinfecting all operatory equipment between patients (linear regression slope for time trend: -0.0001, p-value: 0.7) and used face masks for all staff (linear regression slope: -0.001, p-value: 0.07) (Figure 1). The use of teledentistry decreased significantly over time (linear regression slope: -0.005, slope p-value: 0.0004) from the highest rate reported in February 2021 (15.8%) to the lowest rate in August 2021 (10.0%). Five different IPC practices (screening or interviewing patients before appointments, checking patient temperatures before treatment, checking staff temperatures at shift start, disinfecting frequently touched surfaces, and encouraging distancing between patients) were in place in most practice settings (85%) until March 2021, at which point significant decreases were reported (linear regression slopes: -0.051814, -0.084345, -0.084339, -0.016331, -0.057588 respectively, all slope p-values <0.005). Interestingly, providing patients with masks in the practice setting increased from September 2020 (72.2%) to February 2021 (81.7%), then declined to 77.3% by August 2021 (Joinpoint regression model p-value: 0.0007). Similarly, physical changes to the dental practice to reduce COVID-19 spread increased from 75.5% in September 2020 to a high of 82.3% in March 2021, then declined to 72.9% by August 2021 (Joinpoint regression model p-value: 0.02).

Expanded questions regarding specific IPC procedures were added to the August 2021 survey. Most reported using pre-procedural mouth rinses (63.7%, n=615), high evacuation suction (84.4%, n=814), four-handed dentistry (57.5%, n=555), and limited clinical care to one patient at a time per operatory (78.3%, n=756). About one quarter used dental dams (26.2%, n=253) and limited the number of dental health care professionals present in the operatory during procedures (23.5%, n=227).

Over the entire period of the study, nearly all (97.8%, n=5,431) of the respondents reported that their dental practices screened non-employees for COVID-19 symptoms and possible exposures and did not allow entry any individual with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection, making them exempt from the OSHA Healthcare ETS.15 The OSHA Healthcare ETS requires non-exempt workplaces to have a COVID-19 plan.15 A minority of the respondents (1.1%, n=59) reported that their dental practice allowed people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to enter the setting and so they were not exempt from the OHSHA requirement. Of the non-exempt practices, 45.5% (n=10) of the participants had a COVID plan while 18.2% (n=4) did not, and 36.7% (n=8) were unsure. Overall, nearly half (47.1%, n=397) of the respondents reported their dental practice had a COVID-19 plan, while 21.6% (n=182) did not, and 31.3% (n=264) were unsure.

After adjusting for other dental practice-related characteristics, years of experience and COVID-19 vaccination were not significantly associated with the odds of practicing dental hygiene with eight or more types of IPC (Table I). Practice setting was a significant factor for the number of IPC measures. When compared to dental hygienists in private solo practices, dental hygienists in public health (adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR): 1.96, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.01, 3.80) or academic settings (aOR: 6.41, 95% CI: 1.96, 20.93) had higher odds of practicing dental hygiene with more types of IPC. Higher respirator, but not mask, supply was also associated with significantly higher odds of more types of IPC (aOR: 2.50, 95% CI: 1.80, 3.47). Those who always wore CDC-recommended PPE had significantly higher odds of also practicing with more types of IPC (aOR: 3.32, 95% CI: 2.56, 4.29). Finally, increasing levels of COVID-19 infections in the community were associated with increasing odds of using more IPC (Table I).

Personal protective equipment

Nearly all (89.7%, 13,395 observations) participants reported their PPE use. In areas with little to no community transmission of COVID-19, the CDC recommended dental healthcare workers continue to adhere to standard precautions, whereas more protective PPE was recommended in areas with moderate or greater community transmission.4 Over the period of study (September 2020 through August 2021), most US jurisdictions experienced at least moderate levels of community transmission of COVID-19.5 Only 3.2% (n=167) of respondents reported practicing dental hygiene during a period of minimal community transmission in their state or territory. Most respondents reported always wearing a surgical mask or respirator, eye protection, gloves, and gown during non-AGPs, and this rose slightly over time (linear regression slope: 0.005, slope p-value: 0.004) from 77.1% (n=2,587) in September 2020 to >80% at all surveyed times after March 2021 (Figure 2).

There were more changes over time in the use of PPE during AGPs. In the first month of the survey (September 2020) nearly half of the respondents (49.0%, n=1,644) always wore CDC-recommended PPE; however, this is likely underestimated, as the survey item did not differentiate between PPE used in AGPs versus non-AGPs. In subsequent months, separate items addressed PPE used during AGPs and non-AGPs. From November 2020 through April 2021, more than 61% of the respondents reported always wearing CDC-recommended PPE during AGPs. However, beginning in May 2021 there was a significant decrease over time (linear regression slope: -0.012667, slope p-value: 0.005) in the proportion of respondents who always wore CDC-recommended PPE during AGPs, and by the end of the study period (August 2021) only half (51.2%, n=496) followed CDC-recommended PPE guidelines. In the May 2021 survey, participants were asked how frequently they used a fit tested N95 or equivalent respirator during AGPs. Nearly half (45.6%, n=390) said they wore it all the time, 5.7% (n=49) most of the time, 7.5% (n=64) some of the time, and 41.2% (n=353) never wore a fit tested respirator during AGPs.

Most respondents (91%) reported that their primary dental practice had >7 days' supply of surgical masks each month of the survey; this response did not vary significantly over time (linear regression slope p-value: 0.3). More variations were seen in the proportion of dental practices with >7 days' supply of N95 or equivalent respirators, first increasing significantly from a low of 77.9% (n=2,619) in September 2020 to a high of 83.1% in March 2021 (n=964) (linear regression slope: 0.07046, slope p-value: 0.002), then decreasing significantly until the study ended in August 2021 to 76.7% (n=742) (linear regression slope: -0.016124, slope p-value: 0.013). Respirator supply levels were associated with always wearing CDC-recommended PPE. When compared to participants working in dental practices with ≤7 days' supply of N95 or equivalent respirators, significantly more participants working in dental practices with >7 days' worth of N95 or equivalent respirators reported wearing PPE according to the CDC guidelines (Table II). However, a dental practice days' worth supply of surgical masks was not associated with always wearing PPE according to CDC guidelines (Table II).

Participants reported how frequently they changed masks or respirators. Each month between 39.6 to 45.8% of the respondents changed masks/respirators between each patient, 15.2 to 29.0% between multiple patients, and 24.8 to 29.2% daily (Figure 3). The proportion who changed their masks/respirators only weekly or if soiled or damaged significantly decreased over time from 13.9% (n=117) in September 2020 to 7.08% (n=73) in August 2021 (linear regression slope: -0.006324, slopep-value:0.000001). Frequency of mask or respirator changing seemed associated with PPE supply levels. Most participants reporting changing their mask/respirator between every patient had >7 days' supply in their dental practice (94.9%, n=1,527), compared to 89.3% (n=324) of those who changed their mask only weekly, when soiled, or when damaged. Similarly, most respondents (83.7%, n=1,277) who changed their mask/respirator in between every patient had >7 days' supply in their dental practice, compared to 76.6% (n=279) of those who changed their mask/respirator weekly, when soiled, or when damaged.

A greater than 7-day supply of respirators was associated with higher odds of always wearing CDC-recommended PPE (aOR: 4.38, 95% CI: 3.06, 6.28). Controlling for years of experience, practice setting, mask and respirator supplies, level of community transmission of COVID-19, and IPC, dental hygienists with at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine had 3.53 higher odds (95% CI: 2.21, 5.64) of always wearing PPE according to CDC guidelines as compared to unvaccinated respondents (Table II). Respondents practicing in dental settings with at least the mean number of IPC measures in place had higher odds (aOR: 3.47, 95% CI: 2.65, 4.54) of always wearing PPE according to CDC guidelines as compared with those who had implemented fewer IPC measures. Respondents were most likely to wear CDC-recommended PPE during periods of low COVID-19 community transmission (when N95 or equivalent respirators were not required during AGPs) and high COVID-19 community transmission (Table II).

COVID-19 testing

By the end of the study period (August 2021), half of the participants (50.7%, n=3,533) had been tested for COVID-19 at least once, and 8.8% (n=614) had ever had COVID-19. By August 2021, 6.8% (n=475) of the respondents reported ever meeting a dental patient in person who had a suspected or confirmed case of COVID-19. A slightly larger proportion (10.0%, n= 700) reported ever meeting someone they worked with in person who had a suspected or confirmed COVID-19. In January 2021 more participants rated the importance of rapid COVID-19 testing at their dental practice as extremely or very important for the dental team (60.1%, n=894), than for patients (52.3%, n=785), or themselves (59.6%, n=889).

Open-ended comments

Participants were given the opportunity to provide open-ended comments in the last survey (August 2021). Three main themes relating to PPE and IPC emerged. Respondents were concerned to see a decrease in precautions such as PPE, patient screening, and waiting room disinfection over time, particularly considering increasing SARS-CoV-2 variants and COVID-19 cases. These comments align with the observed declining trends in overall use of PPE and IPC measures and were also consistent with respondents' descriptions of declining supplies of N95 or equivalent respirators in dental practices. Finally, participants expressed frustration over a perceived lack of consistency in guidance and enforcement of safety standards.

Discussion

Throughout the study period, nearly all respondents reported COVID-19 specific IPC in place at their primary practice setting (>99% each month). The majority of practicing dental hygienists also reported always wearing a mask or respirator and eye protection during patient care (>76% each month). However, since the beginning of 2021, significant declines in use of N95 or equivalent respirators during AGPs as well as in some of the IPC methods were reported. Dental practice setting, respirator supplies, COVID-19 vaccinations, and COVID-19 community transmission levels were significantly associated with IPC and PPE use.

The continued use of AGPs, and in some cases increased use, when national guidance advised avoiding these procedures is concerning, particularly in light of the newer SARS-CoV-2 variants. Utilizing ultrasonic instrumentation when hand instruments are readily available may be associated with the misperception that ultrasonic instruments are superior to hand instruments for treating periodontally-involved conditions. A recent meta-analysis comparing hand and sonic/ultrasonic instruments for periodontal treatment demonstrated no significant differences between the two instrumentation modalities in terms of clinical attachment level and probing pocket depth at 3 and 6 month time frames.17 In another systematic review and meta-analysis, ultrasonic and manual scaling was compared at different probing pocket depths along with clinical attachment loss reduction during periodontal treatment.18 Results from this analysis revealed that manual subgingival scaling was superior when initial probing depths were 4-6 mm, and manual scaling was superior in terms of periodontal pocket depth reduction.18 Further findings indicated that when initial probing depths were ≥6 mm, the periodontal probing depth and clinical attachment reductions suggested that manual subgingival scaling produced superior results.18 Clinicians should be able to provide effective patient care without increasing (or generating) aerosols in the operatory environment.

Academic and public health settings had higher rates of PPE usage and IPC measures than private practice settings. Combined with the close association between supply of N95 or equivalent respirators and consistent respirator use, these findings indicate that practice-level policies and resources influence the adherence to CDC guidance or OSHA regulations. Consistent with research in dental practices outside the US,7,8 high community transmission levels of COVID-19 were associated with more types of IPC measures and use of the CDC-recommended PPE. Content analysis of write-in responses showed that most dental hygienists would welcome more guidance and enforcement of the COVID-19 mitigation methods recommended by public health agencies such as the CDC and regulatory bodies such as OSHA.

There are limitations to this study. All the data is based on self-report, which is subject to recall and social desirability bias. There were missing data for 10.3% of the PPE questions, so there may be non-response bias. However, confidence in these findings can be strengthened by the size of the sample population (n=6,976) and representative demographics that included territories, and all states and districts of the US. Further, the study's prospective data collection allowed for a unique evaluation of trends in PPE use and IPC measures over the course of the pandemic in the US. Useful future research could include an evaluation of best practices in maintaining and encouraging COVID-19 risk mitigation procedures in dental settings.

Conclusion

Most dental hygienists indicated always wearing masks and eye protection during patient care. Dental practices have instituted a variety of IPC measures to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Nevertheless, the use of N95 or equivalent respirators and some IPC methods declined during 2021. Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of new variants, there is a need for increased education and policies to support continued use of PPE and IPC as recommended by the CDC and required by government regulatory agencies.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. This research was funded by the American Dental Hygienists' Association and the American Dental Association.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all survey participants for generously sharing their thoughts and experiences.

Cameron G. Estrich, MPH, PhDis a Health Research Analyst, Evidence Synthesis and Translation Research, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, LLC, Chicago, IL, USA.

JoAnn R. Gurenlian, RDH, MS, PhD, AFAAOMis the Director of Education and Research, American Dental Hygienists' Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Ann Battrell, MSDH, is the Chief Executive Officer, American Dental Hygienists' Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Ann Lynchis the Director of Advocacy, American Dental Hygienists' Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Matthew Mikkelsen, MAis the Manager, Education Surveys, Health Policy Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Rachel W. Morrissey, MAis a Senior Research Analyst, Education and Emerging Issues, Health Policy Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Marko Vujicic, PhDis the Chief Economist and Vice President, Health Policy Institute, American Dental Association, Chicago, IL, USA.

Marcelo W. B. Araujo, DDS, MS, PhDis the Chief Science Officer, American Dental Association, Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's statement on IHR Emergency Committee on novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. Geneva (SW): World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2020 July 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Transmission 2020 [Internet] Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021[modified 2021 May 7; cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/sars-cov-2-transmission.html.

3. Innes N, Johnson IG, Al-Yaseen W, et al. A systematic review of droplet and aerosol generation in dentistry. J Dent. 2021 Feb;105:103556.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control guidance for dental settings during the COVID-19 response [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [modified 2020 June 17; cited 2020 June 29]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https:/covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/.

6. World Health Organization. Considerations for the provision of essential oral health services in the context of COVID-19 2020 [Internet]. Geneva (SW): World Health Organization; 2020 [modified 2020 August 3; cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-2019-nCoV-oral-health-2020.1.

7. Bontà G, Campus G, Cagetti MG. COVID-19 pandemic and dental hygienists in Italy: a questionnaire survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Oct 31;20(1):994.

8. Cagetti MG, Cairoli JL, Senna A, et al. COVID-19 outbreak in North Italy: an overview on dentistry. A questionnaire survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May;17(11):3835.

9. International Federation of Dental Hygienists. IFDH 2020 COVID survey [Internet]. Rockville (MD): International Federation of Dental Hygienists; 2020 [cited 2020 July 24]. Available from: http://www.ifdh.org/ifdh-2020-covid-survey.html.

10. Estrich CG, Gurenlian JR, Battrell A, et al. COVID-19 prevalence and related practices among dental hygienists in the United States. J Dent Hyg. 2021;95(1):6-16.

11. Riley RD, Ensor J, Snell KIE, et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ. 2020;368.

12. Araujo MW, Estrich CG, Mikkelsen M, et al. COVID-2019 among dentists in the United States: a 6-month longitudinal report of accumulative prevalence and incidence. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021 Jun;152(6):425-33.

13. Gurenlian JR, Morrissey R, Estrich CG, et al. Employment patterns of dental hygienists in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Hyg. 2021 Feb;95(1):17-24.

14. American Dental Association. ADA interim guidance for management of emergency and urgent dental care 2020 [Internet]. Chicago (IL): American Dental Association; 2020 [cited 2020 May 6]. Available from: https://snlg.iss.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ADA_COVID_Int_Guidance_Treat_Pts.pdf

15. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Occupational Safety and Health Standards: 1910.502 [Internet] Washington, DC: US Department of Labor; 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.502.

16. Morrissey R, Gurenlian JR, Estrich CG, et al. Employment patterns of dental hygienists in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: a research update. J Dent Hyg. 2022 Feb;96(1):27-33.

17. Muniz F, Langa GPJ, Pimentel RP, et al. Comparison between hand and sonic/ultrasonic instruments for periodontal treatment: systematic review with meta-analysis. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2020 Oct;22(4):187-204.

18. Zhang X, Hu Z, Zhu X, et al. Treating periodontitis-a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing ultrasonic and manual subgingival scaling at different probing pocket depths. BMC Oral Health. 2020 Jun;20(1):1-16.