You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

The ADAA has an obligation to disseminate knowledge in the field of dentistry. Sponsorship of a continuing education program by the ADAA does not necessarily imply endorsement of a particular philosophy, product, or technique.

It is important for the dental team to know the appearance of normal anatomy of the face and oral cavity. This knowledge provides a sound basis for identifying abnormal conditions. The dentist holds sole responsibility for diagnosis and treatment of the patient, however, the entire dental team should always be alert for abnormal conditions in all patients' oral cavities. There are, of course, wide variations of what can be considered normal, but with careful attention to detail the dental team will gain confidence and become more adept at identifying conditions that may require further attention.

Normal Anatomic Structures of the Face and Oral Cavity

Regions of the face

The following are the nine regions of the face shown in Figure 1:

1. Forehead

2. Temples

3. Orbital area

4. External nose

5. Zygomatic area

6. Mouth and lips

7. Cheeks

8. Chin

9. External Ear

Facial landmarks

The following are landmarks found on the face shown in Figure 2:

1. Outer Canthus of the Eye: fold of tissue at the outer corner of the eyelids

2. Inner Canthus of the Eye: fold of tissue at the inner corner of the eyelids

3. Ala: outer edge (wing) of the nostril

4. Philtrum: shallow depression between the bottom of the nose and the top of the upper lip

5. Tragus of the Ear: the triangular cartilage projection anterior to the external opening of the ear

6. Nasion: midpoint between the eyes just below the eyebrows

7. Glabella: smooth surface of the frontal bone, directly above the root of the nose

8. Root: commonly called the "bridge" of the nose

9. Septum: this tissue dividing the nasal cavity into two parts

10. Anterior Naris: the nostril

11. Mental Protuberance: forms the chin

12. Angle of the Mandible: lower posterior of the ramus

13. Zygomatic Arch: create the prominence of the cheek

The lips, also known as labia, serve as the opening to the mouth. Figure 3 depicts a frontal view of the mouth and lips.

Tissues and landmarks of the oral cavity

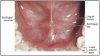

The following are landmarks of the palate. These landmarks are identified in Figure 4.

• Hard Palate: Bony structure that separates oral cavity from nasal cavity.

• Incisive Papilla: Thick keratinized tissue that covers the incisive foramen.

• Palatine Raphe: Midline ridge of tissue that covers the bony suture of the palate.

• Palatine Rugae: Irregular ridges or folds of masticatory mucosa that extend horizontally from either side of the palatine raphe.

• Soft Palate: Forms the posterior section of the palate and is not supported by underlying bone. It can be lifted to meet the posterior pharyngeal wall to seal the nasopharynx during swallowing and speech.

• Uvula: Small conical mass of tissue that hangs from the palatine velum (free edge of the soft palate).

• Fauces: The passageway from the oral cavity to the pharynx (throat).

• Pillars of Fauces: Two arches of muscle tissue surrounding posterior oral cavity. The Anterior Pillar of Fauces is also called palatoglossal arch; the Posterior Pillar of Fauces is also called the palatopharyngeal arch. They contract and narrow the fauces during deglutition (swallowing).

• Isthmus of Fauces: The space between the left and right anterior and posterior pillars of fauces. It contains the palatine tonsils.

The oral cavity is covered with different soft tissues. These tissues are depicted in Figure 5 through Figure 7.

• Masticatory Mucosa: Heavily keratinized tissue that lines the hard palate and tongue.

• Alveolar Mucosa: Lightly keratinized tissue that lines floor of the mouth and covers the alveolar processes.

• Labial & Buccal Mucosa: Thinly keratinized tissue that lines the inner surface of the lips and cheeks.

• Frenum (pl. Frena): Raised lines of oral mucosa that extend from the alveolar mucosa to the labial and buccal mucosa.

• Linea Alba: A raised white line of keratinized tissue on the buccal mucosa that runs parallel to the line of the occlusal plane.

• Parotid Papilla: Flap of tissue found opposite the maxillary 2nd molar on the buccal mucosa and contains the terminal end of the parotid duct also known as the Stenson's duct.

• Oral Vestibule: A pocket formed by the soft tissue of the lips/cheeks and the gingiva, its deepest point is called the "vestibule fornix" or the "mucobuccal fold."

• Fordyce Granules/Spots: Yellowish ectopic sebaceous glands found on the facial mucosa near the corners of the mouth.

Landmarks of the tongue

The following are landmarks of the tongue. These tissues are depicted in Figure 8.

• Dorsum of the Tongue: Superior (top) surface of the tongue.

• Median Sulcus: A centralized linear indentation on the dorsum of the tongue running anterior to posterior.

• Ventral Surface of the Tongue: Inferior (underneath) surface of the tongue. The ventral surface of the tongue is very vascular and covered with thin, alveolar mucosa.

• Apex of the Tongue: Anterior tip of the tongue.

• Filiform Papillae: Small cone shaped papillae found in the anterior 2/3 of the dorsum that are responsible for the sense of touch.

• Fungiform Papillae: Mushroom-shaped papillae spread evenly over the entire dorsum of the tongue. They are deep red in color and each contains a taste bud.

• Circumvallate Papillae (Vallate Papillae): Cup-shaped papillae that are approximately 1-2 mm wide and found on the posterior dorsum of the tongue. They are usually arranged in 2 rows that form a V shape. Each papilla contains a taste bud.

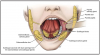

Landmarks of the floor of the mouth

The following are landmarks of the floor of the mouth located under the tongue. These tissues are depicted in Figure 9.

• Lingual Frenum: Midline fold of tissue between ventral surface of the tongue and floor of the mouth.

• Sublingual Caruncles: Two small, raised folds of tissue found on either side of the lingual frenum. They each contain a salivary duct opening for Wharton's Duct (duct leading from the Submandibular Salivary gland).

• Sublingual Folds: Folds of tissue that begin at the Sublingual Caruncles on either side of the lingual frenum and run backward toward the base of the tongue. They contain the many ducts from the sublingual salivary gland.

The salivary glands

Three large paired salivary glands secrete saliva into the mouth. There are minor glands located throughout the mucosal tissues, the palate, and the floor of the mouth. Saliva is necessary for lubrication and aids in the digestive processes. The pairs are depicted in Figure 10.

• Parotid glands: Largest, located in the cheek area, provides approximately 25% of the saliva. Salivary secretions are carried from the gland to the mouth via Stenson's ducts. The parotid papillae, located in the buccal mucosa adjacent the maxillary second molars contain the openings to Stensen's Ducts.

• Submandibular glands: Lies in the submandibular fossa on the lingual surface of the mandible toward the posterior. Salivary secretions are carried from the gland though Wharton's ducts. The sublingual caruncles on either side of the lingual frenum contain the openings to Wharton's ducts.

• Sublingual glands: Located more anteriorly in the floor of the mouth near the base of the tongue. Salivary secretions are carried by multiple short ducts and combine in to a main duct of Bartholin. The sublingual caruncles on either side of the lingual frenum also contain the opening to the ducts of Bartholin.

The Teeth and Their Functions

Around the age of 6 months, most people begin to acquire their first set of teeth known as deciduous teeth or primary teeth. By age 3, there will be 20 teeth that make up the primary or deciduous dentition, 10 in the maxillary arch and 10 in the mandibular arch. The deciduous teeth are eventually exfoliated, or shed, and are replaced by 20 succedaneous teeth which are permanent. In addition to the 20 succedaneous teeth, 12 additional permanent teeth erupt in the posterior areas of the mouth as the jaws continue to grow to make a total of 32 teeth in the permanent dentition by the age of 25.

A child will exhibit a full primary dentition until approximately age of 6. It is at that age when the first permanent teeth begin to erupt. During the time a child exhibits both primary and permanent teeth, they are considered to be in mixed dentition. The mixed dentition phase usually ends around age 12 as the last primary tooth is exfoliated.

There are several types of teeth, and each performs its own special function in the chewing process, depending on its size, shape, and location within the jaws.

• The four front teeth in each arch are called incisors, and their function is to cut food with their sharp thin edges. The two incisors in the middle of the arches are called central incisors. The incisors directly behind and adjacent to the central incisors are called lateral incisors.

• On each side of the lateral incisors, at the corners of the mouth, are the canines. These teeth have one cusp, or pointed edge, are used for holding or grasping food, and are very strong, stable teeth.

• Behind each canine in the permanent dentition are two premolars, which are designed for holding food like canines but because they have two cusps, also function to crush food. Sometimes these teeth are referred to as bicuspids, meaning two cusps, but this is not always accurate because some premolars may have three cusps. Therefore, the term premolar is preferred. There are no premolars in the primary dentition.

• The large teeth farthest back in the mouth are the molars. In the permanent dentition, there are usually three molars found directly behind the premolars. In the primary dentition, there are only two molars and they are found directly behind the canines. These teeth have broad chewing surfaces with four or five cusps and are designed for grinding food.

The incisors and canines as a group are called anterior teeth, because they are located in the front of the mouth, while premolars and molars as a group are called posterior teeth because they are located in the back of the mouth. Figure 11 and Figure 12 show tooth placement for permanent and primary dentitions.

In addition to aiding in acquiring and chewing food, teeth perform several other important functions within the oral cavity. They begin the digestive process by breaking down food, protect the oral cavity, aid in proper speech, and they affect physical appearance of the face.

Morphology and nomenclature

The Universal Numbering System for teeth has been adopted by the American Dental Association and uses numbers 1-32 to designate individual permanent teeth and the letters of the alphabet A-T to designate primary teeth (Diagram 1).

Incisors

There are two incisors in each quadrant, one central incisor and one lateral incisor.

Location and Nomenclature-The central incisors are side by side at the midline.

• The permanent central incisors are teeth #8 and #9 on the maxilla and #24 and #25 on the mandible.

• The primary central incisors are teeth E and F on the maxilla and O and P on the mandible.

There is a lateral incisor found to the distal of each of the central incisor.

• The permanent lateral incisors are teeth #7 and #10 on the maxilla and #23 and #26 on the mandible.

• The primary lateral incisors are teeth D and G on the maxilla and N and Q on the mandible.

Shape-crowns are arched facially and the mesioincisal angle is sharp with the distoincisal angle slightly rounded.

Root-single rooted.

The lingual surface is slightly concave with a cingulum at the gumline.

Function-to cut or incise food with their thin edges.

Canines

There is one canine in each arch. Canines are sometimes referred to as cuspids.

Location and Nomenclature-Canines are found immediately to the distal of the lateral incisors and establish the cornering of the arches.

• The permanent canines are #6 and #11 on the maxilla and #22 and #27 on the mandible.

• The primary canines are C and H on the maxilla and M and R on the mandible.

Shape-the facial is highly convex with a slightly convex lingual surface containing a slight cingulum. There is one cusp at the incisal with the mesioincisal slope shorter than the distoincisal slope.

Root-anchored with the longest root in the arch.

Function-used for holding, grasping, and tearing food. Referred to as the cornerstone of the mouth.

Premolars

There are two premolars in each quadrant. A first premolar and a second premolar. Premolars are sometimes referred to as bicuspids. There are no premolars in the primary dentition and are developed to replace the primary first and primary second molars as the jaws grow in the child.

Location and Nomenclature-

• The first premolars are distal to the canines and are #5 and #12 on the maxilla, and #21 and #28 on the mandible.

• The second premolars are distal to the first premolars and are #4 and #13 on the maxilla and #20 and #29 on the mandible.

Shape-Each premolar has one prominent buccal cusp and one lesser lingual cusp. The mandibular 2nd premolar may have a 2nd lingual cusp.

Roots-

• Maxillary first premolars are bifurcated, which means they have 2 roots. One root is buccal and one root is palatal.

• Maxillary 2nd premolars and all mandibular premolars have one root.

Function-holding food, like canines because they have cusps; also to crush food.

Molars

There are three molars in each quadrant of the permanent dentition and two molars in each quadrant of the primary dentition. They are designated as first, second, or third molars based upon their sequence of eruption. All permanent molars are non-succedaneous in that they do not replace any of the primary teeth. Permanent molars erupt behind the most distal molars of the primary dentition.

Location and Nomenclature-

First Molars

• Permanent first molars are sometimes called "6-year molars" since they erupt around age 6. In the permanent dentition, first molars are found distal to the second premolars but will be seen distal to the primary second molar in younger children who have not yet developed their second premolars. They are #3 and #14 in the maxilla and #19 and #30 in the mandible.

• Primary first molars are found distal to the canines and will eventually be replaced by first premolars (bicuspids). They are B & I on the maxilla and L & S on the mandible.

Second Molars

• Permanent second molars are distal to the permanent first molars. They are # 2 and #15 on the maxilla and #18 and #31 on the mandible.

• Primary second molars are distal to primary first molars and will eventually be replaced by second premolars (bicuspids). In a mixed dentition they will be seen mesial to the permanent first molar. They are A and J on the maxilla and K and T on the mandible.

Third molars-are only found in the permanent dentition and are distal to the permanent second molars. They are the most distal tooth in each quadrant and are sometimes referred to as "wisdom teeth." They are #1 and #16 in the maxilla and #17 and #32 in the mandible.

Shape-molars have broad chewing surfaces with four to five cusps.

Roots-Maxillary molars have 3 roots (trifurcated) with two buccal roots (mesial and distal) and one palatal root. Mandibular molars have two roots (bifurcated) with one mesial root and one distal root.

Function-grinding food.

Divisions of a Tooth

A tooth is divided into two main sections, the crown and the root. The crown is the portion of the tooth that erupts from the bone into the mouth and is used for chewing. The root is the portion of the tooth that remains embedded within the bone, anchoring the tooth to its position in the mouth.

The anatomical crown of a tooth is covered in enamel which is the hardest substance formed by the human body. Sometimes the entire anatomical crown does not become fully erupted and only a part of the anatomical crown is visible in the mouth. The part of the anatomical crown that is visible in the mouth is then referred to as the "clinical" crown. (The word "clinical" is often used to describe anything that is directly visible to the eye.) Understanding the difference between the anatomical crown and the clinical crown is very important, especially when identifying scope of practice regarding expanded functions. In some states, dental assistants may perform certain expanded functions on clinical crowns only. Any remaining part of the crown not visibly erupted would be restricted.

A tooth either will have a single root or will have multiple roots. The area from which a tooth divides into two roots is called the bifurcation; the area from which a tooth divides into three roots is called the trifurcation. Each root has an apex, which is the end of the root or root tip. Each root is covered by a hard, crusty substance called cementum.

The area of the tooth where the crown meets the root is known as the cervix (neck). There is a distinct line at this cervical area where the cementum of the root meets the enamel of the crown. This line is known as the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) or cervical line (Figure 13).

Tissues of a Tooth

There are four tissues that make up a tooth. Enamel, dentin, and cementum are the hard tissues of a tooth. The pulp is the soft tissue.

Enamel, which forms the outer surface of the crown of the tooth, is made of mineral-based crystals consisting primarily of hydroxyapatite (calcium phosphate). Since tooth enamel is 96% inorganic (mineral-based), the tooth is able to withstand a great amount of stress, chewing pressure, and temperature changes. Enamel is somewhat translucent and receives its hue and tint from the underlying dentin and dietary stains. Enamel is formed within a tooth bud prior to eruption by specialized cells called ameloblasts. All ameloblasts are lost upon eruption and therefore the tooth does not have the ability for further enamel growth or repair. However, if the enamel does experience minor demineralization close to the surface due to exposure to bacterial plaque and dietary acids, it does have the ability to remineralize by adding calcium, phosphate, and fluoride if found in the mouth and saliva. This process can stave off caries and prevent the loss of tooth structure. Remineralization can only occur when adhering to proper nutrition and oral care.

Dentin comprises the chief substance of the tooth and is found in both the crown and root portions of the tooth. In the crown the dentin is covered by enamel and in the root the dentin is covered by cementum. Dentin is softer than enamel but harder than cementum and bone. There are two components of dentin: peritubular dentin and intertubular dentin. Peritubular dentin is the hardened component of dentin and consists of a mineralized substance of carbonated apatite crystal. Peritubular dentin forms hollow tubules with microscopic canals. Each hardened tubule contains the soft intertubular dentin consisting of a collagen dentinal fiber and fluid. This fiber and its fluid transmit pain stimuli and other substances throughout the tissues of the tooth. The dentin is formed by specialized cells called odontoblasts. Live odontoblasts remain in the pulp cavity at the end of each dentinal tubule and continues to form dentin within the pulp cavity as long as the tooth remains vital. There are three types of dentin: primary, secondary, and tertiary dentin.

The dentin that forms in the tooth bud prior to tooth eruption is called primary dentin. The dentin that forms after tooth eruption is called secondary dentin. Since this secondary dentin will continue to grow throughout the life of the tooth, it will result in the narrowing of the pulp canal as the person ages. The third (tertiary) type of dentin, also known as reparative dentin, forms quickly and thickly as a response to pulpal irritation and trauma such as deep dental caries.

Cementum is a thin layer of hard tissue that covers the dentin in the root of the tooth. It is not as hard as enamel or dentin, but it is slightly harder than bone. Cementum is formed by specialized cells called cementoblasts. Cementum helps anchor the tooth in the boney socket by attaching to the fibers of the periodontal ligament. (The periodontal ligament is also anchored to the bone of the tooth socket.) There are two types of cementum. Primary cementum, or acellular cementum, covers the coronal two-thirds of the root. Acellular cementum does not have growth capability since cementoblasts do not remain with this area of cementum once it is formed. When a tooth has erupted and has reached functional occlusion, secondary cementum, or cellular cementum, continues to form on the apical third of the root. Cellular cementum contains living cementoblasts and can repair any cementum in that area that becomes damaged. If any of the root's cementum becomes exposed in the mouth due to periodontal disease or other injury, the cementum will be quickly worn away leaving exposed dentin in the mouth.

The pulp is located in the center of the tooth and is surrounded by dentin. The pulp cavity is divided into two areas: the pulp chamber, located in the crown of the tooth; and the pulp canal(s), located in the root(s) of the tooth. When a tooth first erupts, the pulp chamber and canal are large, but as secondary dentin forms, they decrease in size. The pulp is composed of blood vessels, lymph vessels, connective tissue, nerve tissue, and odontoblasts; therefore, the pulp is protective, builds dentin, and nourishes various tissues of the tooth. The nerve supply in the pulp exits through a small foramen (hole) in the apex of the root and transmits the signals of sensitivity and pain to the brain. If the pulp tissues become diseased or necrotic (die), then a root canal procedure is recommended to prevent the loss of the tooth to subsequent infection (Figure 13).

Surfaces of Teeth

In order to identify specific locations on a tooth, it is divided into surfaces and each surface has a specific name. The surfaces are named according to the direction in which they face (Figure 14). The surfaces of teeth and their universal abbreviations are as follows:

• Lingual (Li) - the surface of a tooth facing the tongue.

• Facial (F) - the surface of a tooth facing the cheeks or lips. Specific names are sometimes used when referring to a facial surface of an anterior tooth or posterior tooth:

o Labial (La) - the surface of an anterior tooth facing the lips.

o Buccal (B) - the surface of a posterior tooth facing the cheeks.

• Proximal surfaces are the surfaces of a tooth that face an adjacent tooth's surface; each tooth has two proximal surfaces:

• Mesial (M) - the surface of a tooth that is closest to the midline.

• Distal (D) - the surface of a tooth that faces away from the midline.

• Occlusal (O) - the chewing surface of posterior teeth.

• Incisal or Incisal Edge (I) - the biting edge of anterior teeth.

Anatomical Landmarks of the Teeth

Depending on the type of tooth and where it is located in the mouth, it is important to be able to recognize the various anatomical structures of a tooth. Each tooth has certain features that set it apart. The contact point where a tooth touches another tooth is often at the height of contour, or the widest bulging point. An embrasure is the triangular space radiating facially, lingually, occlusally/incisally, or gingivally from the contact point of adjacent teeth. The interdental papilla is a small projection of gum tissue that can be found in the gingival embrasure. Figure 15 identifies additional landmarks found on certain anterior or posterior teeth.

Arrangement of the Teeth in the Oral Cavity

Arches

The teeth are arranged in the oral cavity in two separate arches in such a way that they will function properly as the position of each tooth is maintained. The arches get their names from the bones of the face in which they are located. The maxillary arch is found in an immovable bone called the maxilla. The mandibular arch is found in a movable bone called the mandible. The maxilla is located above the mandible so therefore maxillary teeth are the upper teeth and the mandibular teeth are the lower teeth (Figure 16).

Quadrants

Each arch can be divided in half by an imaginary vertical line drawn through the center of the face (the midline). Each half of the arch is called a quadrant. Thus there are four quadrants: maxillary right, maxillary left, mandibular right, and mandibular left (Figure 16).

Occlusion

Occlusion is the contact between the maxillary and mandibular teeth in any functional relationship. Normal occlusion is important for optimal oral functions, for prevention of dental diseases, and for esthetics. Normal occlusion is established by a fine balance between the maxillary and mandibular jaw sizes and positions, and the proper shapes and sizes of each tooth. Any deviation from normal occlusion is considered as malocclusion. Malocclusion may involve a single tooth, groups of teeth, or entire arches. With malocclusion, oral functions may be affected, such as difficulty in chewing, swallowing, and speech; it may also cause pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Malocclusion may be caused by several factors including heredity, diseases that disturb dental development, injuries, and habits such as thumb sucking or tongue thrusting.

Classifications of Occlusion

Angle's classification system is a common method used to classify various occlusal relationships. This system is based upon the relationship between the permanent maxillary and mandibular first molars. Figure 17 shows the classifications of occlusion as well as the facial profiles of each.

Dentitions

The term dentition refers to the natural teeth in the dental arches. There are two major dentitions: primary and permanent. In children between the ages of approximately 5 and 12, each arch will contain a mixture of primary and permanent teeth. This is referred to as mixed dentition.

Primary dentition

The primary dentition refers to the first twenty teeth to erupt in the oral cavity. These teeth are also called deciduous teeth and will be exfoliated (shed) to make way for the permanent teeth. There are 20 teeth in the primary dentition: there are 2 central incisors, 2 lateral incisors, 2 canines, 2 first molars, and 2 second molars in each arch. Table 1 shows the average eruption and exfoliation (shedding) dates of the primary dentition.

Permanent dentition

The permanent dentition contains 32 teeth, with each arch having 2 central incisors, 2 lateral incisors, 2 canines, 2 first premolars, 2 second premolars, 2 first molars, 2 second molars, and 2 third molars. This period of dentition begins when the last primary tooth is shed. The 20 permanent teeth that replace primary teeth are called succedaneous teeth. The permanent molars are not succedaneous teeth because they do not replace any primary teeth. The primary molars are replaced with the permanent premolars. Table 2 shows the eruption dates of the permanent dentition.

Communicating tooth names: D-A-Q-T system

The correct sequence of words when describing a tooth is based on the D-A-Q-T system. D stands for dentition, A stands for arch, Q stands for quadrant, and T stands for the tooth type. The dentition is named first, followed by the arch, then the quadrant, and finally the tooth name. For example, a primary first molar would be identified as the primary maxillary right first molar. A permanent central incisor would be identified as the permanent mandibular left central incisor. Teeth can also be referred to by number/letter.

Periodontium

The periodontium consists of the hard and soft tissues that help to anchor, support, and protect the teeth. It is made up of the gingival unit and the attachment unit. Figure 18 illustrates the components of the periodontium.

Gingival unit

The gingival unit consists of the gingiva (soft tissues that surround the teeth) and the alveolar mucosa (soft tissues that line the oral cavity).

Gingiva-The gingiva, also known as gum tissue, surrounds the teeth and can be attached to the underlying bone (attached gingiva) or unattached (free gingiva). When healthy, the gingiva should be firm and well adapted to the teeth and have a stippled appearance. This means that its texture appears similar to an orange peel. The color of healthy gingiva depends on the pigmentation of each person, but in general it should appear light pink.

Alveolar Mucosa-The alveolar mucosa consists of the tissue inside the cheeks, vestibule (the space between the lips or cheeks and the teeth), lips, soft palate, and under the tongue. This tissue is more movable and is lightly attached to the underlying bone and muscles. Its texture is smooth, and its color is red to bright red. A stronger, more keratinized (contains keratin) mucosa lines the surface of the tongue and the hard palate to protect it during mastication (chewing) of food. This keratinized mucosa is called masticatory mucosa.

Attachment unit

The attachment unit consists of the cementum, the alveolar bone (bone surrounding the teeth), and the periodontal ligaments (fibers or ligaments that anchor and support the teeth in their sockets).

Cementum-The cementum is the tooth tissue covering the root of the tooth. Periodontal ligament fibers are imbedded in the cementum and serve to anchor the teeth in their sockets.

Alveolar Bone-The alveolar bone is also called the alveolar process. It is the bone that forms the sockets for the teeth. The lamina dura is a thin, crusty layer of compact bone that lines the tooth sockets of the alveolar bone and serves to anchor the periodontal ligament to the socket.

Periodontal Ligament (PDL)-The periodontal ligament (sometimes called the periodontal membrane) is connective tissue arranged into groups of fibers based on their anatomic location: alveolar crest fibers; horizontal fibers; oblique fibers; periapical fibers; and interradicular fibers. The insertion ends of the principle fibers that are attached to the cementum on the tooth side and to the lamina dura on the bone side are called Sharpey's fibers. There are also gingival fibers of the periodontal ligament that insert into the cervical gingivae to support the gingival margin around the tooth.

Summary

A working knowledge of normal anatomy of the face and oral cavity is critical for the entire dental team. This is one of many facets necessary in providing oral healthcare. The ability to recognize normal versus abnormal tissue conditions is important during the oral examination process. Having a working understanding of dental terminology will assure effective communication between team members and other healthcare providers and is an important component to the overall health and well-being of the dental patient.

Glossary

Adjacent - next to, or nearby.

Alveolar mucosa - lightly keratinized tissue that lines floor of the mouth and covers the alveolar processes.

Anterior - toward the front.

Apex - the end of the root of a tooth.

Apical foramen - the opening at the end of the root of a tooth.

Bifurcated - one tooth with two roots.

Bifurcation - the area in a two-rooted tooth where the roots divide.

Buccal - the surface of a posterior tooth facing the cheeks.

Cementoenamel junction (CEJ)/cervical line - the area of a tooth where the cementum of the root and the enamel of the crown meet.

Cementum - the tissue covering the root of a tooth.

Cingulum - a smooth, rounded bump on the cervical third of the lingual surface of anterior teeth.

Contact area - the area on the proximal surface of a tooth where it touches an adjacent tooth.

Coronal - pertaining to the crown; the area nearest the crown of the tooth.

Deciduous teeth - the first set of teeth; the primary teeth, commonly known as baby teeth.

Dentin - the tissue of a tooth that comprises the main inner portion of the tooth; it is covered by cementum on the root and enamel on the crown.

Dentition - set of teeth; the natural teeth in position in the dental arches.

Distal - means situated away from the midline; the distal surface of a tooth (D) is farthest away from the midline.

Embrasure - the triangular-shaped areas formed around the contact points of adjacent teeth facially, lingually, incisally/occlusally, and gingivally.

Enamel - the hardest tissue in the body, the outermost layer of the teeth.

Facial - means situated toward the lips and/or cheeks; the facial surface of a tooth faces either the lips (anterior teeth) or cheeks (posterior teeth); the term "facial surface" is used when it is necessary to be inclusive to both anterior and posterior labial and buccal surfaces.

Fissure - a groove or natural depression on the surface of a tooth.

Fossa - a shallow, rounded or angular depression on the surface of a tooth.

Gingiva - the mucous membrane tissue that surrounds the teeth.

Gingival sulcus - the space between the tooth and the free gingiva.

Hard palate - bony structure that separates oral cavity from nasal cavity.

Incisal - cutting edge of anterior teeth; situated toward the cutting edge of the edge of an anterior tooth.

Incisive foramen - a passageway through the bone of the hard palate for vessels and nerves; found just lingual to the central incisor region.

Interproximal - between the proximal surfaces of adjacent teeth.

Interradicular - between roots.

Labial - means situated toward the lips: the labial surface of anterior teeth face the lips.

Lingual - the surface of a tooth that faces the tongue.

Mandibular - pertaining to the lower jaw (mandible).

Maxillary - pertaining to the upper arch (maxilla).

Mesial - means situated nearest the midline; the mesial surface of a tooth is closest to the midline.

Midline - an imaginary vertical plane that divides the body or a structure into equal right and left halves.

Mucogingival junction - the line or area where the alveolar mucosa meets the attached gingiva.

Mucosa - the tissue lining the oral cavity.

Occlusal - the biting surface of a posterior tooth; situated toward the biting surface of a posterior tooth.

Periapical - the area surrounding the apex of a tooth.

Periodontium - the tissues that surround and support the teeth; includes the gingiva, the alveolar mucosa, the cementum, the periodontal ligament, and the alveolar bone.

Posterior - toward the back.

Pulp - located in the center of the tooth, composed of the living tissues such as blood vessels and nerve tissue.

Quadrant - one-fourth of the mouth; half of the maxillary or mandibular arch.

Succedaneous - permanent teeth that replace primary teeth.

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) - the freely moveable synovial joints formed as the mandible (lower jaw) articulates with the left and right sides of the skull in an area anterior to the ears.

References

Finkbeiner, BL and Johnson, CS, Mosby's Comprehensive Dental Assisting: A Clinical Approach, Normal Structures of the Oral Cavity

Fehrenbach, MJ and Kerring, SW, Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, 3rd Edition, Fig 2-17

Fehrenbach, MJ and Kerring, SW, Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, 3rd Edition, Fig 2-19

Applegate, EJ, The Anatomy and Physiology Learning System, 2nd Edition, p. 333

Bird et al, Modern Dental Assisting, 12th Edition

Bath-Balogh, M and Fehrenbach, MJ, Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, pp. 330-332

About the Author

Kimberly Bland

Kimberly Bland is a certified dental assistant and the Program Director for the Dental Assisting Program at Manatee Technical College in Bradenton, Florida. She has authored many professional articles, has been a contributing author to several ADAA continuing education courses, and has lectured extensively on many dental related topics.

Kimberly graduated from the CODA accredited dental assisting program she now leads and has remained in the field since 1982 working clinically, administratively, and academically. She is a graduate of the University of South Florida with a Baccalaureate degree in Industrial and Technical Education and a Master's Degree in Educational Leadership.

She served as the president of the American Dental Assistants Association in 2007-2008 and again in 2014-2016. She is a founding Director and first President of the Professional Dental Assistants Association Foundation.