You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Successful endodontic treatment is predicated upon correct pulpal and periradicular diagnoses. It is paramount that endodontic etiology be identified before any endodontic treatment is initiated. The diagnostic process begins with a review of the patient’s medical and dental history, and also includes taking the patient’s blood pressure and pulse. Secondly, the clinician must listen to the patient’s perception of the problem (subjective) and then perform clinical testing (objective) to reproduce the patient’s subjective pain symptoms. There is often confusion among clinicians as to which test to perform to arrive at pre-treatment pulpal and periradicular diagnoses. Below are five objective clinical tests used to determine the pulpal and periradicular diagnoses:

1. Heat/cold tests and/or EPT for pulp vitality.

It is important to note that heat and cold tests do not jeopardize the health of the pulp.1 In addition, teeth with porcelain or metal crowns do conduct temperature and, therefore, can be tested for pulpal vitality with cold or heat.2

There is often confusion regarding what the numerical readings on an electric pulp test (EPT) represent. Although the use of an EPT can establish pulp vitality, the numerical readout should not be used to determine the overall health of the pulp.3 For example, if tooth No. 8 has an EPT reading of 12 and tooth No. 9 has an EPT reading of 24, it does not mean tooth No. 8 is deemed twice as vital as tooth No. 9. The EPT is used to determine if the pulp is vital or not. When using an EPT, be aware that teeth with metal restorations can give false-positive or false-negative responses.

In a study by Weisleder and colleagues,4 the investigators reported that cold test and EPT used in conjunction resulted in a more accurate method for diagnostic testing.

2. Percussion tests for determining the status of the periodontal ligament.

This test is often mistakenly considered to directly correlate to a pulp’s vitality. Although a tooth’s sensitivity to percussion tests may be due to a pulpitis or pulpal necrosis, it is only indirectly associated. All this specific test helps to determine is the status of the periodontal ligament (Figure 1). A bite test may also need to be performed if a patient complains about pain upon mastication.

3. Palpation of the buccal and lingual gingival tissue of the tooth in question.

The palpation examination tests for the sensitivity of the gingival tissue and the cortical and medullary bone for infection and/or inflammation (Figure 2). It is important to note that even when there is no radiographic evidence of an apical infection, clinically, an infection may be present. Bender and colleagues5 reported that it is not uncommon to have extensive disease of the bone when there is no evidence on a radiograph.

4. Periodontal examination.

This test should include both periodontal probing and assessment of tooth mobility.

5. Current radiographic examination.

This can include periapicals, bitewings, and/or cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT).

Pulpal Diagnosis

Nociceptors are sensory receptors that respond to potentially damaging stimuli by sending nerve signals to the brain. This stimulus can cause the perception of pain in an individual. Pulpal nerve fibers A-delta and C-fibers are nociceptors.6,7

Reversible pulpitis is pain from an inflamed pulp that can be treated without the removal of the pulp tissue. It should be noted that this is not a disease, but a symptom. Classic clinical symptoms are sharp, quick pain that subsides as soon as the stimulus is removed. Physiologically, it is the A-delta fibers that are firing, not the C-fibers of the pulp.8 A-delta fibers are the myelinated, low-threshold, sharp/pricking pain nerve fibers that reside principally in the pulp-dentin junction. They are stimulated by cold and EPT and cannot survive in a hypoxic (low oxygen) environment. Reversible pulpitis also does not involve unprovoked (spontaneous) response.

Irreversible pulpitis is an inflamed pulp that cannot be treated except by the removal of the pulp tissue. It can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Classic clinical symptoms of irreversible pulpitis are lingering of cold/hot stimulus greater than 5 seconds and/or patient reporting of spontaneous tooth pain. Physiologically, it can be the A-delta fibers and/or the C-fibers firing neural impulses. C-fibers are the unmyelinated, high-threshold, aching pain nerve fibers. They are distributed throughout the pulp. They are stimulated by heat and can survive in a hypoxic environment.

Pulpal necrosis can occur as a result of an untreated irreversible pulpitis or immediately after a traumatic injury that disrupts the vascular system of the pulp. A necrotic pulp does not respond to cold tests, EPT, or heat tests.

In 2013, the endodontic pulpal diagnostic terminology adopted by the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) in 20099,10 was incorporated into the National Board Dental Examination, Part II, by the Joint Commission on National Dental Examinations (JCNDE).

Periradicular Diagnosis

When clinicians think of endodontic treatment, they often focus only on the pulpal diagnosis. Although this diagnosis is important prior to performing root canal treatment, making a periradicular diagnosis is just as important. As with the changes in pulpal diagnosis, in 2013, the endodontic periradicular diagnostic terminology adopted by the AAE in 20099 was incorporated into the National Board Dental Examination, Part II, by the JCNDE (Table 1).

Symptomatic apical periodontitis is characterized by a tooth that has a painful response to biting and/or percussion. This may or may not be accompanied by radiographic changes.

Asymptomatic apical periodontitis is suspected when the tooth has no pain to percussion or palpation, and the radiograph reveals apical radiolucency.

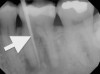

Chronic apical abscess is typically indicated by a radiograph that reveals a radiolucency. Clinically, there is a sinus tract present on the gingival tissue. It is paramount that the draining sinus tract be traced with a gutta-percha cone and then radiographed (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Acute apical abscess is an inflammatory reaction to pulpal infection and necrosis characterized by rapid-onset spontaneous pain, extreme tenderness of the tooth to pressure, pus formation, and swelling of associated tissues. There may be no radiographic signs of destruction, and the patient often experiences malaise, fever, and lymphadenopathy.

Odontogenic vs. Nonodontogenic Diagnosis

There are many nonodontogenic pain symptoms that mimic endodontic pain symptoms.11 If a patient’s subjective description of pain is “tingling,” “electric-like,” “burning,” or “hurts on both sides of my face,” the etiology may be nonodontogenic in origin.

The gray areas of diagnosis appear when there are inconsistencies between a patient’s subjective description and the clinician’s objective diagnostic tests. A clinician who suspects the diagnosis is odontogenic but cannot localize the etiology should consider prescribing medication(s) to help localize the symptoms; alternatively, the patient could be referred to a dental specialist for further evaluation.

Prescribing anti-inflammatory or antibiotic medications and then having the patient return for re-evaluation can sometimes help in definitive reaching a diagnosis. Some dentists believe treatment necessarily involves use of a high-speed drill, not just a prescription for medicine. Of course, this is not at all the case in medicine, where the protocol is often limited to pharmacologic treatment. A dentist who renders treatment without identifying the etiology of the complaint is more likely to have a patient quickly lose confidence due to treatment that does not relieve his or her symptoms. Dentists who refer their patients to an endodontist should never feel this reflects poorly on their professional ability; on the contrary, patients respect their practitioner’s decision to refer them to a specialist to ensure optimal care.

The use of selective anesthesia can also be a helpful aid in diagnosis. Although there are exceptions, if local anesthesia dissipates the patient’s pain, the etiology is generally odontogenic. If local anesthesia is not effective in eliminating pain, the etiology is usually nonodontogenic. The implementation of selective anesthesia should be the last test performed during diagnostic procedures, because the tooth or teeth involved cannot be further tested for sensitivity afterward at that appointment.

Another helpful aid in diagnosis is to have a patient keep a short daily diary. Patients often either describe their pain in generalities or have difficulty remembering exactly what triggers the pain when they are sitting in a dental chair (dental patient anxiety). It is not until they are asked to make notes of specific incidences of pain that they can better communicate it to the dentist. An example of an excerpt from a patient’s diary could be being awakened by pain at night (spontaneous pain suggests a diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis) or feeling the pain when drinking coffee in the morning, but that it is quickly relieved after drinking cold orange juice (C-fiber stimulation suggests a diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis).

Heterotopic pain or secondary pain are symptoms that are perceived to originate from a site that is different from the actual source of the pain.11 That is why, from an endodontic diagnostic perspective, when teeth test within normal limits to the five objective diagnostic tests, the clinician must be aware that the source of the pain may be different from the site of the pain. Primary pain involves symptoms that are perceived to originate from a site that is the same as the actual source of the pain.11 This type of pain is very common in endodontic pain etiology.

If after thorough review of diagnostic tests, the dentist feels that the etiology is nonodontogenic, then he or she should refer the patient to a physician (usually a neurologist) or a dental specialist (oral surgeon or maxiofacial pain specialist) for further diagnostic evaluation and possible treatment.

Summary

An endodontic diagnosis cannot be formulated by the patient’s subjective description (chief complaint) and a dental radiograph alone. It is important that a dentist obtains a pulpal and periradicular diagnosis prior to initiating any endodontic treatment. The information from the medical and dental history—which includes taking a patient’s blood pressure and pulse—must be performed along with the five odontogenic objective tests described: pulp vitality; percussion (may include bite testing); palpation; periodontal probing/tooth mobility; and radiographic assessment.

When a dentist evaluates the data from these five objective clinical tests along with the medical and dental history in conjunction with the patient’s chief complaint, the site of the pain must correlate to the source of the pain. If there are inconsistencies between the site and source correlation of pain, no dental treatment should be initiated. The dentist must reevaluate the testing data and consider the possibility of nonodontogenic origin of pain. Often in the case of nonodontogenic pain, the patient subjectively experiences the pain as coming from a specific tooth or teeth, while the tooth or teeth in question test within normal limits to the five objective endodontic diagnostic tests. If a dentist has difficulty in deriving a definitive odontogenic or nonodontogenic diagnosis, he or she should feel comfortable referring the patient to an endodontist, oral surgeon, or a maxillofacial pain specialist for further patient evaluation.

Disclosures

Dr. James Bahcall has no financial interest in any of the products mentioned in this article.

About the author

James K. Bahcall, DMD, MS, FICD, FACD, is a professor at University of Illinois-Chicago School of Dentistry in Chicago, Illinois. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics and Fellow of the International and American Colleges of Dentists. He is a pioneer and leading authority on fiber-optic and endoscopic visualization in the field of endodontics. He is the recipient of outstanding teaching awards and has published numerous scientific articles, as well as written chapters for endodontic textbooks. He serves as a member of the Scientific Advisory Boards of the Journal of Endodontics, Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, and Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. Dr. Bahcall lectures on endodontics worldwide.

References

1. Rickoff B, Trowbridge H, Baker J, et al. Effects of thermal vitality tests on human dental pulp. J Endod. 1988;14(10):482-485.

2. Miller SO, Johnson JD, Allemang JD, Strother JM. Cold testing through full-coverage restorations. J Endod. 2004;30(10):695-700.

3. Lado EA, Richmond AF, Marks RG. Reliability and validity of a digital pulp tester as a test for measuring sensory perception. J Endod. 1988;14(7):352-356.

4. Weisleder R, Yamauchi S, Caplan DJ, et al. The validity of pulp testing: a clinical study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(8):1013-1017.

5. Bender IB, Seltzer S. Roentgenographic and direct observation of experimental lesions in bone I. 1961. J Endod. 2003;29(11):702-706.

6. Loeser JD, Treede RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain. 2008;137(3):473-477.

7. Mattscheck D, Law A, Nixdorf D. Diagnosis of nonodontogenic toothache. In: Hargreaves KM, Berman LH, eds. Cohen’s Pathways of the Pulp. 10th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier: 52.

8. Kim S. Neurovascular interaction in the dental pulp in health and inflammation. J Endod. 1990;16(2):48-53.

9. American Association of Endodontists. Glossary of Endodontic Terms. 8th ed. Chicago, IL: 2012. www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/aae/endodonticglossary/index.php#/0. Accessed August 26, 2015.

10. AAE Consensus Conference Recommended Diagnostic Terminology. J Endod. 2009;35(12):1634.

11. Okeson JP. Bell’s Oral and Facial Pain. 7th ed. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co., Inc.; 2014:69.