You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

In the United States, it is estimated that anywhere from five to ten million females and approximately one million males struggle with some type of eating disorder. The disorder does not discriminate and affects men, women, and adolescents from all ethnicities. The group most commonly affected is adolescent girls, but diagnoses are increasing in males and other age groups, most notably women in their fifth decade of life. Dental personnel are usually the first to notice changes in the oral cavity of individuals with certain types of eating disorders. The earlier treatment is sought in the disease process, the more hopeful the prognosis. Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. Unfortunately, between five percent and 20 percent of the individuals with long-term eating disorders will die as a result of the illness.

Etiology of Eating Disorders

“Eating disorder” is a term used to describe health and psychological disorders characterized by a disturbance in one’s attitude and behaviors relating to eating, body weight, body image and thoughts about one’s self. There are many different types of eating disorders, all of which may be encountered within the dental field.

The etiology of eating disorders is multifactorial and influenced by biological, cultural, psychological, and social factors. All eating disorders may have similar physical oral manifestations, and it is the oral complications that eventually lead the individual to the dental office. Since the allied dental professional is the person most likely to take the medical/dental history and provide the first oral exam, he or she must be the first to be able to identify the disease. Allied dental professionals are not as threatening to the patient as the dentist. Because of this, they are the perfect choice for a confidant. Counseling and treatment for the specific eating disorder is not among the dental professional’s responsibilities, but restoring oral problems and the prevention of oral complications caused by the disease is both necessary and expected.

There are three main eating disorders commonly seen in the dental field, and several lesser-known disorders. The most commonly seen disorder is bulimia nervosa, followed by anorexia nervosa and binge eating.

Eating is a completely instinctive behavior for animals. It serves a surprising number of purposes for humans. Eating practices may identify bonds among cultural, ethnic and family groups; take on religious meanings; and be a means of expressing hostility, affection, prestige, and class values. Equally, providing, preparing and dispensing food may be a means of expressing love or hatred, or even power in some family relationships. Eating disorders are developed, stemming from biological, psychological, and social or interpersonal situations that lead to a preoccupation with food. These disorders can begin at a very early age. Given these possibilities, it is not surprising that some eating disorders take on odd habits, progressing from normal responses to hunger and satiety cues through obsessive weight loss, to a full-blown eating disorder (Table 1).

Food can represent much more than nutrients. From birth, food is linked with personal emotional experiences. An infant associates milk with security and warmth, so the bottle or breast becomes a source of comfort as well as food. Foods are often used as a reward: “You can’t watch television until you clean your plate,” “If you love me, you’ll eat what I fix for dinner,” “I’ll eat my vegetables if you let me play video games.” These statements are often heard while a person is growing up. At first glance, this practice of foods as rewards appears harmless enough, but eventually both caregivers and children can build behavior patterns that use foods to achieve unusual goals. Food then takes on a much larger role. At the extreme, when food is regularly used as a tool of expressions rather than simply as a source of nutrition, it can contribute to disordered eating patterns. At their worst, these patterns form the links to later anorexia nervosa.

Biological factors are not well described, but progressive starvation and subsequent abnormal metabolism of protein and fat substrates seem to perpetuate the anorexic state, along with unbalanced brain chemicals that signal and control hunger and satiety. Psychological factors of eating disorders include anger, anxiety, depression, and feelings of inadequacy or lack of control in life, loneliness, and low self-esteem.

There is a correlation between interpersonal and social factors as they relate to eating disorder etiology. Interpersonal factors include difficulties in family and other relationships and in expressing emotions or feelings, a history of being teased about weight, and/or a history of sexual abuse.

The media plays a huge role in propagating eating disorders by employing unnaturally thin models and insinuating that all should aspire to look like them. The media misrepresents perfectly thin bodies as being preferable over curvy or well-proportioned ones. Approximately 80% of American women are dissatisfied with their appearance; the average American woman is 5’4” tall and weighs 140 pounds. Compare that to the average American model who is 5’11” tall and weighs 117 pounds. Disillusionment about size seen in media affects all age groups: roughly 81% of 10 year olds are afraid of being fat while 51% of the same 10 year olds feel better about themselves if they are on a diet; approximately 91% of women on college campuses attempt to control their weight through dieting and 95% of all dieters will regain their lost weight in one to five years. Annually, approximately $33 billion in revenue is made on the diet and diet-related industry.

Common Types of Eating Disorders

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa have been written about as far back as the Middle Ages.

Anorexia nervosa is a serious, often chronic, and life-threatening eating disorder defined by a refusal to maintain minimal body weight within 15 percent of an individual’s normal weight. Other key features of this disorder include an extreme fear of gaining weight, a distorted body image, muscle wasting, and amenorrhea. In addition to the classic pattern of restrictive eating, some people will also engage in recurrent binge eating and purging episodes. Starvation, weight loss, and related medical complications are quite serious and can result in death. Anorexia nervosa is among the psychiatric conditions having the highest mortality rates, killing up to six percent of its victims.

The term anorexia literally means loss of appetite, but this is a misnomer. In fact, people with anorexia nervosa ignore hunger and thus control their desire to eat. Obsessive exercise may accompany the starving behavior as a result of the distorted body image.

Conservative estimates suggest that one-half to one percent of females in the U.S. develop anorexia nervosa. Other reports state that anorexia nervosa occurs in approximately one out of 100 adolescent females and is most frequently found in middle-to-upper socioeconomic groups.

A familial component appears to be present, with female relatives most often affected. A female has a ten to twenty times higher risk of developing anorexia nervosa if she has a sibling with the disease. This finding suggests that genetic factors may predispose some people to eating disorders.

Behavioral and environmental influences may also play a role. Stressful events are likely to increase the risk of eating disorders as well. Since more than 90% of all those who are affected are adolescent and young women, the disorder has been characterized as primarily a woman’s illness. It should be noted, however, that males and children as young as seven years old have been diagnosed; and the symptoms of women aged 50 to even 80 years have fit the diagnosis.

Persons with anorexia usually lose weight by reducing their total food intake and exercising excessively. Many persons with this disorder restrict their intake to fewer than 1,000 calories per day when at least 2000 calories is recommended. Most avoid fattening, high-calorie foods and eliminate meats. The diet of persons with anorexia nervosa may consist almost completely of low-calorie vegetables like lettuce and carrots, or popcorn.

Early Warning Signs and Symptoms of Anorexia Nervosa

The trademark of anorexia nervosa is a preoccupation with food and a refusal to maintain minimally normal body weight. At first, dieting becomes the focus of their life. One of the most frightening aspects of the disorder is that individuals with anorexia continue to think they look fat even when they are extremely thin. Food and weight become obsessions as people with this disorder constantly think about their next encounter with food.

As the stress in the individual’s life increases, sleep disturbances and depression prevail. Other psychiatric disorders can occur together with anorexia nervosa, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder. Calorie intake may continue to decrease to as little as 300 to 600 kilocalories a day. In place of food, the individual may consume up to 20 cans of diet soft drinks daily. Persons with anorexia nervosa generally fall into two categories: (1) those who practice extreme food restriction behaviors (AN-R) and (2) those who display food binge/purge behavior (AN-BP). Once a person loses more than 15% of normal body weight, there is a greater risk of lifetime suffering from the disorder. After losing more than 25% of normal body weight, a cure becomes very difficult, hospitalization is almost always necessary, and premature death is more likely.3

Medical and Physical Symptoms of Anorexia Nervosa

There are many physical symptoms of anorexia nervosa that may mimic symptoms of other medical conditions. The patient’s medical history must be correctly maintained to reflect the resulting medical conditions.

Eating disorders, especially one such as anorexia, play havoc with the overall body health. The anorexic is often 20% to 40% below desirable body weight and appears emaciated. This state of semistarvation disrupts many body systems as it forces the body to conserve as much energy as possible. Hormonal responses to semistarvation can cause an array of predictable effects.3

- Lowered body temperature due to a loss of fat insulation and slower basal metabolism. The slowed basal metabolism is caused by a decrease in the synthesis of the active thyroid hormone and the loss of lean body mass.4

- The heart rate decreases as the metabolism slows, leading the individual to fatigue and faint easily, and experience a tremendous need for sleep.

- Pulse rate and blood pressure drop, and individuals may experience irregular heart rhythms or heart failure. Cardiovascular effects include supraventricular and ventricular dysrhythmias, long QT syndrome, bradycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and shock due to congestive heart failure.

- Iron-deficiency anemia, which leads to further weakness.

- Rough, dry, scaly, and cold skin.

- The appearance of lanugo on the body that traps air, insulating against heat loss and replacing some of the insulation lost with the fat layer.

- Low white blood cell count due to lack of protein and zinc. This condition increases the risk for infection, a cause of death in some anoretic people.

- Loss of hair from the scalp.

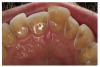

- Constipation from semistarvation, poor nutrient intake, and sometimes-laxative abuse. Additional gastrointestinal findings include delayed gastric emptying, gastric dilation and rupture, dental enamel erosion (Figure 1), palatal trauma, enlarged parotids, inflammation of the esophagus, Mallory Weiss lesions, diminished gag reflex, and elevated transaminases.

- Eventual deterioration of teeth due to frequent vomiting. Poor dental health and loss of bone mass can be lasting signs of the disorder, even if the other physical and mental problems are resolved. Additional oral signs in the disordered state include anemic tissues and chapped lips.

- Low blood potassium, (hypokalemia) because of poor nutrition, and possible vomiting and use of diuretics. Hypokalemia increases the risk of heart rhythm disturbances, another leading cause of death among anorexics.

- Renal disturbances include decreased glomerular filtration rate, elevated BUN, edema, acidosis with dehydration, hypochloremic alkalosis with vomiting, and hyperaldosteronism.

- Absence of menstrual periods because of low body weight, low fat content, and the stress of the disorder. The accompanying hormonal changes cause a loss of bone mass and an increase in the risk of osteoporosis.

- Poor outcome of pregnancy, such as poor fetal growth and development, especially if a woman begins pregnancy in an anoretic state.

- Protein deficiency and disruption of multiple organ systems; other nutritional deficiencies may appear, including hypoglycemia and multiple vitamin deficiencies.

- Bone marrow suppression may occur, leading to platelet, erythrocyte, and leukocyte abnormalities.

As a dental professional, you may notice the following physical symptoms when the individual with anorexia is in your chair:

- avoidance of eye contact,

- dehydration,

- dry brittle skin and nails,

- painfully thin appearance,

- the appearance of light fuzzy hair on face,

- low blood pressure,

- and complaints of always being cold.

Treatment of Anorexia

Treatment usually includes a team of physicians, registered dieticians, psychologists, and other health professionals working together. Often, the ideal setting is an inpatient eating disorders clinic in a medical center,5 as this location can take the anorectic person away from the many environmental influences that encourage the disorder. Once the medical team has gained the cooperation of the patient, they work together to restore a sense of balance, purpose and future.

Nutrition Therapy

One of the first goals of therapy is increasing the individual’s food intake. Enough weight must be gained to raise the basal metabolism to normal and to reverse the many physical signs of the disease as possible. Weight gain is not the sole goal of treatment, but rather a prelude to fuller engagement in psychological issues.6

Experienced professional help is crucial. Today, suicide is the most common cause of death in anoretic individuals.8 Additionally, anorectic individuals are often very clever and resistant. They may try to hide weight loss by wearing many layers of clothes, putting coins in their pockets before being weighed or drinking numerous glasses of water. Health professionals tend to measure and compare weight for height to standards because assessments of “thin” can and are distorted by very thin models in advertisements and the media.

Psychological Therapy

The key aspect of psychological treatment is showing the individual how to regain control over their lives and how to cope through stressful situations. Therapists work to help individuals accept setbacks and to regard these setbacks as opportunities to learn more about themselves rather than as sources of despair and disappointment. There is no specific pharmacological agent used to treat anorexia nervosa. Increasing intake of food is the drug of choice. Medications used typically depend on the physician and the individual – each case is different. Some of the more commonly prescribed medications when treating anorexia nervosa when accompanied by depression include:

- Tranylcypromine sulfate (Parnate)

- Imipramine (Tofranil)

- Amitriptyline (Elavil)

- Desipramine (Norpramine)

- Lithium carbonate (Lithane)

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) is used to decrease anxiety about eating and is used successfully by many.

The general prognosis is related to the severity of the underlying personality and family psychopathology. The prognosis for individuals with a bulimic component is worse than for those without the component. Death occurs in five to 40 percent of the individuals with the bulimia component in addition to the anorexia. A small percentage of individuals become symptom free; thirty percent remain chronically ill, and the rest are vulnerable to the return of symptoms during stressful times. Establishing a strong relationship with either a therapist or other supportive person is the answer to recovery, and key to success.

Bulimia Nervosa

First diagnosed in the 1980s, initially experts believed that bulimia was an eating disorder caused by an individual’s reaction to stress and/or depression. Later, studies indicate that bulimia may be caused by some biological and hereditary conditions as well as emotional and psychological factors.

Results of a 1999 study, published by the American Medical Association’s Archives of General Psychiatry, indicated that bulimia could be the result of a chemical imbalance in the brain. When deprived of the amino acid tryptophan, recovered bulimic women reported mood swings, a return to pre-occupation with body image, and anxiety over their ability to retain control over their eating habits.10 Tryptophan, a natural part of many foods, helps the brain produce serotonin, which is a mood and appetite-regulating chemical. In an unrelated study, Dr. Walter H. Kaye of the University of Pittsburgh also reported finding abnormal levels of a serotonin-related chemical in the spinal fluid of actively bulimic women.10

Bulimia nervosa literally means “ox hunger” or hungry as an ox.1 Bulimia is a serious eating disorder marked by a destructive pattern of binge-eating and recurrent inappropriate behavior to control one’s weight. The disorder can occur together with other psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance dependence, or self-injurious behavior.

Binge eating is defined as the consumption of excessively large amounts of food within a short period of time. The food is often sweet, high in calories, and has a texture that makes it easy to eat fast. Inappropriate compensatory behavior to control one’s weight may include purging behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas; or non-purging behaviors such as fasting or excessive exercise. For those who binge eat, sometimes any amount of food, even a salad or half an apple, is perceived as a binge and is vomited. Bulimia binge cycles are a vicious cycle of obsession coupled with unhealthy behavior and interspersed with feelings of anxiety, fear, triumph, and guilt (Figure 2).

People with bulimia nervosa often feel a lack of control during their eating binges. Their food is usually eaten secretly and gobbled down rapidly with little chewing, and the binge is usually ended by abdominal discomfort. When the binge is over, the person with bulimia feels guilty and purges to rid his or her body of the excess calories. To be diagnosed with bulimia, a person must have had, on average, a minimum of two binge-eating episodes a week for at least three months.

Bulimia frequently begins in adolescence or early adulthood. Like anorexia nervosa, bulimia mainly affects females. Only 10% to 15% of affected individuals are male. An estimated 2% to 3% of young women develop bulimia, compared with the one-half to one percent that is estimated to suffer from anorexia. Studies indicate that about 50% of those who begin an eating disorder with anorexia nervosa later become bulimic.

Three Types of Bulimia

Bulimia nervosa is best considered as three separate illnesses that share the essential features described above. There is quite a lot of overlap between them, so there are a number of sufferers who show characteristics between these subgroups.

Simple Bulimia Nervosa

Simple bulimia nervosa is an illness that begins most commonly when the girls are about 18 years of age. The illness is frequently triggered by a period of unhappiness, which is often caused by a destructive relationship with a boyfriend. The feeling of self-dislike focuses on appearance, and dieting is begun in an attempt to improve self-esteem.

In contrast to an anorectic, the diet is not very successful. Rigid control of food intake breaks down into bouts of cheating. Vomiting is used as part of increased efforts to achieve the weight loss and so the cycle of bingeing and vomiting begins. There is more loss of control as the body’s normal mechanisms of appetite control are overridden and confused. The weight will remain close to normal but the eating pattern becomes gradually worse. This form of bulimia is the least severe, but the severity varies considerably. It is likely that there are large numbers of girls with fairly mild symptoms that never come for medical help, but there is a significant risk that it will slowly get worse with time. A common time for sufferers to seek help is when they are planning to start a family in their early twenties and are concerned about possible effects on having babies.

Anorexic Bulimia Nervosa

Anorexic bulimia nervosa is a variant of the disorder that is preceded by a bout of anorexia nervosa. Quite often this anorexic episode is a brief one and the sufferer begins to recover without treatment. It is followed typically by a short period of stabilized weight just below that at which the menstruation may restart, around 100 pounds. The control of the anorexic is not constant and bingeing begins usually in a very small way, but becomes more severe, especially once vomiting begins. Often they begin by vomiting after what would for a normal person be an ordinary meal, but this leads to a loss of control of the appetite drive and true bingeing gradually starts.

Occasionally the vomiting and bingeing start first, but then there is a period of significant weight loss in an anorexic phase that includes restrictive eating. The illness becomes dominated by the bingeing and vomiting behavior, but the weight remains low for a while before gradually rising to near and in time above normal. The personality profile and backgrounds of these girls is similar as for a group with anorexia nervosa. The bulimic individuals seem to be slightly less obsessive and to be slightly more mature in emotional development.

Multi-Impulsive Bulimia Nervosa

Multi-impulsive bulimia is a severe variant of bulimia nervosa that begins in a similar way to simple bulimia and in a similar age group of girls. This group suffers with a range of abnormal behaviors, all of which indicate problems of emotional and impulse control. Often some of these other behaviors are already causing difficulty before the bulimia begins.

In connection with the eating disorder will be found a mix of other problems including drug abuse, alcohol abuse, deliberate self-harm, stealing, and promiscuity. They have difficulty modifying their behavior because of predictable consequences of their actions. As a result, helping them to change the pattern of their lives often requires prolonged help. The severity of the illness, as with all types of bulimia, is varied and in this group it seems to depend on severity of the underlying abnormal personality.

Signs and Symptoms of Bulimia

Common indicators of the self-induced vomiting associated with bulimia include several oral findings. Erosion of dental enamel due to the acidic vomit will be present and scarring on the backs of the hands may be seen due to repeatedly pushing fingers down the throat to induce vomiting.

A small percentage of bulimic patients show swelling of the parotid glands in the cheeks. A depressed mood is also commonly observed, as are frequent complaints of sore throats and abdominal pain.

Additional oral signs can include brittle enamel, chapped lips, chronic sore throat, dentinal hypersensitivity, erythematous oral tissues and red palate, extrusion of amalgam restorations, moderate to severe dental caries due to binge-food selection, oral pain, unaesthetic appearance of teeth, and xerostomia. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III-R) of the American Psychiatric Association lists specific criteria in the diagnosis of both anorexia nervosa and bulimia (Appendix 1).2 Symptoms of both eating disorders overlap considerably, such that a person may exhibit characteristics of both disorders.

Despite these telltale signs, bulimia is difficult to catch early. Binge eating and purging are often done in secret and can be easily concealed by a normal-weight person who is ashamed of his or her behavior, but uncontrollably compelled to continue. Characteristically, these individuals have many rules about food, such as there being “good foods and bad foods,” and they can be ingrained in these rules and particular thinking patterns.

Medical Complications of Bulimia

As with anorexia nervosa, patients with bulimia can severely damage their bodies and the medical history must be current to properly treat the patient. Electrolyte imbalance and dehydration can occur and may cause cardiac complications and, occasionally, sudden death. In rare instances, binge eating can cause the stomach to rupture, and purging can result in heart failure due to the loss of vital minerals like potassium. Repeated vomiting causes a loss of stomach contents and because this includes the acid secretions that are needed for digestion it leads to changes of body chemistry. Laxative abuse causes similar distortion of chemistry and the two behaviors together are most likely to be dangerous. Major disturbance of the blood chemistry, particularly loss of potassium, and rupture of the stomach are occasional causes of sudden death, but fortunately this is rare unless the behavior is extreme. Acid from the stomach constantly washing over the teeth dissolves the enamel and will cause lasting damage, particularly to the four central upper teeth. Irregularity of the menstrual cycle is common and sometimes it stops altogether. There is an association of ovarian cysts with the illness that is likely to reduce fertility but most are able to conceive normally once they are recovered. The greatest risks to the individual are from suicide or self-harm as a result of depression and feelings of hopelessness.

Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa

Simple bulimia nervosa often runs a fairly benign course and there are probably many girls who have mild illnesses, never ask for help, and yet give it up successfully. When more severe, it is often an illness that can be successfully treated on an outpatient basis. In experienced hands the outcome of such treatment is good.

Anorexic bulimia nervosa is more likely to need inpatient or day patient care if the weight remains low, since restoration of normal weight is essential to appetite control. Correspondingly the outcome is a little more guarded but many will do well. Ultimately the outcome depends on the severity of the underlying problems and their successful resolution.

Someone with multi-impulsive bulimia nervosa is only likely to seek treatment when the consequences are severe. The sufferers are usually unlikely to want change. As a result, they often need inpatient care in a highly structured environment where they can be prevented from acting out in self-destructive ways. This is the most difficult of the types of bulimia to treat and the one with the least good outcome. Despite that, many girls will eventually make good recoveries.

Therapists may prescribe antidepressants such as amitriptyline (Elavil) and tranylcypromine (Parnate) to combat some depression associated with bulimia. These medications help with reducing bingeing urges in early phases of treatment. Fenfluramine (Pondimin) may also be used in an attempt to curb appetite during treatment of some cases of bulimia.

Binge Eating: The New Disorder

Binge eating disorder is a newly recognized condition that probably affects millions of Americans, and is considered one of the main eating disorders along with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. People with binge eating disorder frequently eat large amounts of food while feeling a loss of control over their eating. This disorder is different from binge-purge syndrome of bulimia because people with binge eating disorder usually do not purge afterward by vomiting or using laxatives.

Doctors are still debating the best ways to determine if someone has binge eating disorder. Characteristics of serious binge eating problems include: frequent episodes of eating what others would consider an abnormally large amount of food, and frequent feelings of being unable to control what or how much is being eaten. Eating behaviors may include eating much more rapidly than usual or until uncomfortably full, eating large amounts of food, even when not physically hungry, and eating alone out of embarrassment at the quantity of food being eaten. Many times feelings of disgust, depression, or guilt after overeating are experienced.

Although it has only recently been recognized as a distinct condition, binge eating disorder is probably the most common eating disorder. Most people with binge eating disorder are obese (more than 20% above a healthy body weight), but normal-weight people also can be affected. Binge eating disorder probably affects 2% of all adults, or about one million to two million Americans. Among mildly obese people in self-help or commercial weight loss programs, 10% to 15% have binge eating disorder.

Binge eating disorder is slightly more common in women, with three women affected for every two men. The disorder affects blacks as often as whites; its frequency in other ethnic groups is not yet known. Obese people with binge eating disorder often became overweight at a younger age. They also may have more frequent episodes of losing and regaining weight (yo-yo dieting).

Etiology of Binge Eating Disorder

The etiology of binge eating disorder is still unknown. Up to half of all people with binge eating disorder have a history of depression. Whether depression is a cause or effect of binge eating disorder is unclear; it may be unrelated. Many people report that anger, sadness, boredom, anxiety or other negative emotions can trigger a binge episode. Impulsive behavior and certain other psychological problems may be more common in people with binge eating disorder.

The major complications of binge eating disorder are the diseases that accompany obesity. These include diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, gallbladder disease, heart disease, and certain types of cancer. Individuals with binge eating disorder are extremely distressed by their binge eating. Most have tried to control it on their own but have not succeeded for very long. Some people miss work, school, or social activities to binge eat.

Physical symptoms of binge eating also include liver and kidney problems, decreased mobility, obesity, osteoarthritis, shortness of breath, increased risk of cardiac arrest and even death.

Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (ED-NOS)

This category is for eating disorders that do not meet the criteria for any specific eating disorder. Examples are shown in Table 2.

Compulsive Overeating Disorder

Compulsive overeating disorder is characterized by uncontrollable eating urges and consequential weight gain. A person with compulsive overeating disorder has a history of marked weight fluctuations. Food is used as a comfort mechanism and to de-stress the individual. This disorder is seen more frequently in males than females. It is estimated that compulsive overeating is much more prevalent than either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Signs and symptoms of compulsive overeating disorder include:

- Eating large amounts of food when not physically hungry.

- Eating much more rapidly than normal.

- Eating until the point of feeling uncomfortably full.

- Eating alone because of shame or embarrassment.

- Experiencing feelings of depression, disgust, or guilt after eating.

Compulsive overeating is different from anorexia nervosa, and particularly bulimia nervosa, because it doesn’t necessarily involve a persistent concern with body shape, weight, and thinness. In addition, not all obese individuals compulsively overeat, so obesity and this disorder are not necessarily associated. Compulsive overeating has been classified, as an addiction to food because psychological dependence is involved.11 There is an attachment to behavior, a drive to control it, a sense of limited control over it, and a need to continue it despite negative consequences. After a while, individuals do not eat because they are hungry and to satiate physical needs, but in response to emotional needs and pain. Those that become compulsive overeaters grow up nurturing others instead of themselves, avoiding their feelings and take little time for themselves.

Treatment for Compulsive Overeating Disorder

Treatment for compulsive overeating disorder usually involves some form of therapy. The individual must learn to eat in response to biological signals (hunger) rather than emotions and external factors like time of the day or presence of food. Dieting is avoided as part of therapy as this may intensify emotional feelings towards food. Individuals must learn to identify their personal needs that are unmet and find healthy ways to satisfy these needs.

Overeaters Anonymous is a self-help group that has been devoted to help overeaters achieve recovery. Participation in this program is often helpful for many. Encouragement and accountability is supplied to individuals who attend, with the philosophy of the organization being similar to Alcoholics Anonymous.

Lesser-Known and Unofficial Eating Disorders

Eating disorders can include some combination of the signs and symptoms of all of the recognized disorders above. While these behaviors may not be clinically considered a full syndrome eating disorder, they can still be physically dangerous and emotionally draining. All eating disorders require professional help as a part of the battle.9

“Unofficial eating disorders” is a generic category created in order to include disorders that describe certain patterns of eating or body-image related behavior created by third parties such as authors, the media, etc. They are not official in the sense that they do not appear in the diagnostic systems either as recognized disorders or, as in the case of binge eating disorder, as research criteria.

Anorexia Athletica

The term anorexia athletica was first used in the 1980s by N.J. Smith in the article, “Excessive Weight Loss and Food Aversion in Athletes Simulating Anorexia Nervosa” published in Pediatrics in July (1980 66(1) pages 139-142); and by Pugliese MT et al. in their article, “Fear of Obesity. A Cause of Short Stature and Delayed Puberty,” published in The New England Journal of Medicine, September 1983 (volume 309 page 513-518).9

Anorexia athletica is sometimes called compulsive exercising or activity anorexia. Many people who are preoccupied with food and weight exercise compulsively in attempts to control weight. The real issues are not weight and performance excellence, but rather power, control, and self-respect. Several studies suggest that those who participate in sports that emphasize appearance and a lean body are at risk for developing an eating disorder. Time is usually taken away from school or work to exercise. Individuals with this disorder are rarely satisfied with physical achievements and move from one challenge to the next. This disorder is most often recognized in competitive athletes, but it can affect anyone with a preoccupation with weight and/or diet. Anorexia athletica goes hand in hand with anorexia nervosa and compulsive exercising.

Warning signs associated with anorexia athletica and medical complications of anorexia athletica are shown in Table 3.

As with any type of eating disorder, there are changes that occur to the body when extreme food habits are exercised (Table 4).

Cardiovascular health requires that 2,000 to 3,500 calories be burned each week in some form of aerobic exercise. Running, jogging, dancing, and brisk walking are just a few examples of cardiovascular exercise that can be accomplished by thirty minutes of exercising a day for five days a week. After 3,500 calories are burned per week, the health benefits decrease and the risk of injury to the body increases. Individuals who suffer from anorexia athletica tend to burn triple the amount of recommended calories, sometimes more.

It has long been recognized that there is a higher than normal prevalence of eating disorders in athletes and indeed a great deal of research has been done in this field. Sundgot-Borgen used the term anorexia athletica to define a sub-group of athletes with eating disorder symptoms that do not permit a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa to be made and would therefore fall within the boundaries of Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (ED-NOS) (assuming DSM-IV is used to provide the diagnostic criteria).9 At the same time, as not a formal eating disorder, it might be surmised that individuals to whom the term anorexia athletica could be (correctly) applied would have an eating disorder categorized under ED-NOS.9 Technically, anorexia athletica should refer only to female athletes but it tends to be applied to either gender.9

Baryophobia

Baryophobia, literally “the fear of becoming heavy,” is a relatively new disorder.12 The term applies to children and young adults who grow slower and less than the norm. Decreased growth in a child usually reflects disease. If no hormonal or other abnormality can be found, the possibility of baryophobia is investigated.

This disorder occurs when parents put their children on the same low-fat, high carbohydrate diet that adults follow. Adults do this in an attempt to prevent their children from developing obesity or heart disease later in life. Well-intended efforts to prevent obesity can lead them to severely restrict food intake of their children. The child doesn’t get enough kilocalories to maintain an adequate growth rate. In young adults, the low kilocalorie may be self-imposed to avoid perceived risk of obesity.

Bigorexia (Muscle Dismorphia)

Bigorexia is sometimes referred to as “reverse anorexia” or “muscle dysmorphia,” and is a newly diagnosed disorder. It is a term used to describe behavior in which the individual has a distorted view of their self and believes that they are too small in a muscular sense, when they are within normal limits. This type of behavior is sometimes seen in bodybuilders and strength training athletes. This false perception can be severely socially disabling with individuals afraid to be seen in public. When these individuals do venture out in public, they wear large clothes to hide their “small” bodies.

Although unrecognized as a true diagnosable eating disorder, some members of the scientific community do consider bigorexia to be linked to eating disorders, in particular anorexia nervosa. The two are linked in that similar body image distortions and extreme preoccupations to remedy the situation occur. The use of steroids and anabolic agents and the associated health risks to achieve the desired goal may be seen to be strikingly similar to the use of laxative, diuretics and diet pills with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.9 These individuals are also very likely to have confidence and coping issues in common with anorexia nervosa individuals. Bigorexia is considered to affect more men than women and there may be connections between bigorexia and anorexia nervosa in terms of perceived gender ideals.9

Orthorexia Nervosa

Whereas anorexia nervosa is an obsession with the quantity of food one eats, it is also possible to be obsessed with eating foods of a certain quality or location where they are eaten. Orthorexia nervosa, a relatively new term coined by Steven Bratman, M.D., refers to a pathological fixation on eating “proper” foods. “Ortho” means straight and “orexia” refers to appetite.

While it is customary for people to change what they eat to improve their health, treat an illness or to lose weight, individuals with orthorexia nervosa may take the concern too far. In the case of orthorexia nervosa, people remain consumed with what types of food they permit themselves to consume, and feel poorly about themselves if they fail to stick to their “proper” diet. Most must resort to an iron self-discipline reinforced by a hefty dose of superiority over those who eat “junk food”. Over time, what to eat, where to eat, how much to eat, and the consequences of dietary indiscretion come to occupy a greater and greater part of the orthorexic’s day. Such people are sometimes called “health food junkies.” However, in some cases, orthorexia goes beyond a mere lifestyle choice. Obsession with healthy food can progress to the point where it crowds out other activities and interests, impairs relationships, and even becomes physically dangerous. When this happens, orthorexia takes on the dimensions of a true eating disorder, like anorexia nervosa or bulimia.

People suffering from this obsession may display the following signs shown in Table 5.

While orthorexia nervosa is not a formal medical condition, many healthcare professionals do feel that it explains an important and growing health phenomenon. Since there is lacking diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis, it is unclear whether individuals following extreme dietary practices for religious or moral reasons would be considered. Any connections with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder are also unclear.9

“This transference of all of life’s value into the act of eating makes orthorexia a true disorder. In this essential characteristic, orthorexia bears many similarities to the two well-known eating disorders anorexia and bulimia. Where the bulimic and anorexic focus on the quantity of food, the orthorexic fixates on its quality. All three give food an excessive place in the scheme of life.”9

Pica

Pica is an eating disorder usually defined as the persistent eating of nonnutritive substances for a period of at least one month at an age in which this behavior is developmentally inappropriate, in most cases over the age of two years.

The definition occasionally is broadened to include the mouthing of nonnutritive substances. Individuals presenting with pica have been reported to mouth and/or ingest a wide variety of nonfood substances, including, but not limited to, clay, dirt, sand, stones, pebbles (known as geophasia), hair, feces, lead, laundry starch, vinyl gloves, plastic, pencil erasers, ice, fingernails, paper, paint chips, coal, chalk, wood, plaster, light bulbs, needles, string, cigarette butts, wire, and burnt matches.

Although pica is observed most frequently in children, it is the most common eating disorder seen in Africa, the Middle East, and China, and in individuals with developmental disabilities. Pica can occur during pregnancy and when a person is lacking certain nutritive deficiencies like iron. Pica may be benign, or it may have life-threatening consequences.

The effects on the body can vary according to what is ingested. Ingestion of poisons and infectious agents is common with pica. Lead toxicity is the most common type of poisoning associated with pica. Lead has neurological, hematologic, endocrine, cardiovascular, and renal effects. Various infections and parasitic infestations, ranging from mild to severe, are associated with the ingestion of infectious agents via contaminated substances, such as feces or dirt.

Eating Behaviors in Children

There are a number of eating difficulties found in children that are not commonly considered to be eating disorders because they lack formal diagnostic criteria and classification. It is argued by some that these childhood eating difficulties are not eating disorders because they seem to have different causes and symptoms and require different treatment modalities. Included are some examples of childhood eating difficulties.

Food Avoidance Emotional Disorder

Food avoidance emotional disorder is a condition in which emotional problems affect appetite and result in the avoidance of food. This can be mistaken for child onset anorexia nervosa, but there are a number of differences. Notably it is considered that the avoidance of food results from symptoms of emotional difficulties such as depression or worry that affects the appetite and is not an attempt to use food to suppress these difficulties. The sufferer will often be aware of their eating difficulties and thinness, unlike the distorted body image that can occur in anorexia, and often expresses a desire to eat more. Food avoidance emotional disorder sufferers also are not considered to have preoccupations with weight or aspirations to be thin.

By avoiding food, the individual does not receive the proper nutrition needed for overall health, growth and maintenance. This is particularly important during the growing years in childhood. A lack of certain vitamins and minerals could affect body systems permanently, particularly the lack of calcium and vitamin D. If the body does not receive enough calcium and vitamin D during the growing years, osteoporosis in later years, and rickets in childhood could result. The child may be more prone to bone fractures, and the dentition may not fare well during the cavity prone years.

Food Refusal Syndrome

Food refusal syndrome is a term given to a behavior of refusing food as a way of the child getting its own way. In some situations this may simply be getting a more preferred food over what is served. The pattern of refusal is often erratic and inconsistent and generally is not thought to pose a risk to the child’s overall physical health. Despite appearing to be manipulative, it is often felt that some form of stress, sadness or an upsetting experience may underlie the abnormal behavior. As the child matures, the behavior tends to disappear.

Restrictive Eating Disorder

Restrictive eating disorder is a term given when a child generally eats a broad and well-balanced range of foods, but noticeably restricts the quantity of food eaten at each sitting. The reasons for this type of behavior are unclear. Some clinicians argue that this type of behavior may result from a learned or observed behavior, such as watching parents as they diet or where others in the household exhibit restrictive eating. Others believe it may simply be that a child has a naturally small appetite. A child with restrictive eating may be below normal height and weight norms for their age, but due to their generally well-balanced diet, are often considered to be healthy. There does not appear to be any preoccupation with weight or aspirations to be thin, and because the diet is well balanced, it is believed that there is no risk to overall health.

Selective Eating Disorder

A child having a very narrow range of “safe” or “acceptable” foods characterizes selective eating. This may be limited not only to specific food types and textures, but in extreme situations, specific brands of foods. A child may become very distressed if attempts are made to encourage or force the child to eat foods outside of their “safe” range. A child may also avoid situations such as picnics and birthday parties where food will be present. There is not necessarily restriction in the amount of food eaten from within the acceptable range.

There does not seem to be a group of foods common to selective eating and as a result, the consequences of the problem can be dependent on the type and range of foods taken. Malnutrition must be considered if the food range does not expand over all food group types. Body weight may be high, low or normal and as such is not a good indication of the condition.

Dental problems may occur if the child’s acceptable range of food has a high content of sugary foods and liquids. Selective eating disorder does not seem to include the obsession with weight and the desire to be thin that are components of anorexia nervosa. As the child matures, they tend to outgrow this eating phase.

Other Food-Related Disorders

There are a number of other disorders that are sometimes considered to be related to eating disorders because they share symptoms with traditional eating disorders. These disorders are often conditions in their own right with their own diagnostic criteria.

Body Dismorphic Disorder

Body dysmorphic disorder, (BDD) is listed in the DSM-IV under somatization disorders, but clinically, it seems to have similarities to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). BDD is a preoccupation with an imagined physical defect in appearance or a vastly exaggerated concern about a minimal defect such as a scar or composition of a feature. The preoccupation must cause significant impairment in the individual’s life, with the individual thinking about his or her defect for at least an hour per day. BBD affects about two percent of the population in the United States, with 70% of cases appearing in males and females before the age of 18. This disorder may sometimes overlap with anorexia nervosa or bulimia.

Other behaviors that may be associated with BDD are listed in Table 6.

BDD is sometimes associated with eating disorders in that the body dysmorphia can be seen to have similarities with the dissatisfaction with, and distorted view of, body shape and size as seen in anorexia nervosa.

Food Phobias

Food phobia is frequently listed as an eating problem in children. Specific phobias were previously called “simple phobias” and are now recognized by both DSM-IV and ICD-10. These are conditions in which sufferers experience a strong, persistent fear in the presence of, or thought of, specific items. A ‘specific phobia’ may be given a name identifying the type of phobic stimuli, for example arachnophobia - phobia of spiders.9

When the phobia is related to food or the process of eating, the fear and avoidance of eating can show eating disorder-like symptoms. There are a number of specific phobias that can fall into this category (Table 7).

Any of the above types of phobias will have an impact on nutrition and overall body health. Nutrients needed to maintain healthy oral tissues may be deficient, resulting in various dental conditions such as caries and periodontal disease.

Night Eating Syndrome

Night eating syndrome (NES) is another condition that does not have diagnostic criteria. Because of this, definitions may vary. In this condition, the sufferer has little appetite in the morning or early in the day, and eating is delayed for a considerable time. Individuals with NES generally eat significantly in the evening. Some definitions of NES require more than 50% of the daily food intake to be consumed after 8pm or the evening meal. Many NES suffers may get up during the night to eat, sometimes multiple times. There is generally an associated feeling of guilt or unhappiness during these times of eating.

NES affects the body in many ways. Excessive caloric intake during the hours normally reserved for body maintenance when we sleep can turn into excess fat. Depending on the type of food consumed during nighttime hours, the dentition may be susceptible to an increased risk of decay if the mouth is not brushed or at the very least, rinsed prior to returning to sleep. The body also suffers during the daytime, especially mid morning when it has been several hours since the last intake of nutrients. Blood glucose levels can fall sharply and brain function can be impaired. Sleep patterns are affected by the frequent rising to eat during nocturnal hours. The body needs its “downtime” for maintenance of cells and tissue repair.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a complex anxiety disorder recognized by both DSM-IV and ICD-10, the criteria for which are quite complex but which can include a variety of distressing rituals, fears, repetitive and intrusive thoughts and compulsive actions.9 Obsession-like behavior around food and/or dieting may present eating disorder-like symptoms. Some also believe that OCD and eating disorders may be related in some way. It is not uncommon for someone to suffer both an eating disorder and OCD.

Dental Team Considerations

The population is becoming increasingly diverse. Such diversity is certainly experienced within the dental patient population, which in turn makes it essential for the dental team to be aware of their ethical and legal obligations when treating patients with unique needs. Individuals with psycho-social issues such as those who may have a current eating disorder or may have had one in the past, all require special knowledge and attention.

Treatment for all eating disorders involves medical investigation, psychological help and nutritional counseling. The sooner a diagnosis is made, the better the outcome. Antidepressants are usually prescribed once weight is stabilized and eating behaviors are under control. Dental care is part of the recovery program. Oral effects of gastric acids and bingeing on cariogenic foods are usually the reason for a visit to the dental office. The acidity of the gastric contents plays havoc on the enamel of the teeth, and can begin erosion of dental restorations. The enamel on the lingual surfaces of the maxillary anterior teeth is often affected the worst by the frequent onslaught of acidic contents. When the enamel is eroded, cariogenic foods have direct contact on the dentin of the tooth. The organic nature of dentin registers discomfort and pain with each eating and binging occurrence.

Comprehensive dental treatment is postponed until behavior is changed so that tooth damage does not continue. Choice in restorative dental treatment depends on mental health status and severity of damage to the teeth. Composites, overlays, crowns and veneers can restore the teeth – depending upon severity of the erosion, and are placed once stability is achieved; restoring teeth to a more aesthetic appearance helps increase self-esteem. Fluoride and sodium bicarbonate rinses can prevent further sensitivity and caries from acids and cariogenic foods during recovery treatment. Maximum benefits are achieved when both systemic and topical fluorides are used together.

Systemic fluorides are also known as dietary fluorides. They are ingested in water, food, beverages, or supplements. Fluoride in the saliva works with calcium and phosphate, also found in saliva to encourage the formation of new crystals to remineralize the damaged area. The dentist may prescribe dietary fluoride supplements, in the form of drops or tablets.

Topical fluorides are known as non-dietary fluorides and are those that are directly applied to the teeth through mouth rinses, fluoridated toothpastes and topical fluoride application. The frequency of professional topical applications depends on the client’s needs and on the type of fluoride used. The most commonly used topical fluoride is an acidulated fluoride gel that is easily applied in a disposable tray after the patient’s teeth have been thoroughly cleaned. To maximize the benefit of this type of fluoride, the patient is advised not to eat or drink for 30 minutes after the treatment. A 1.1 percent neutral sodium fluoride brush-on gel is available without prescription. A two percent neutral sodium fluoride brush-on gel is available by prescription. Patients may use these at home by brushing them or through application with a reusable custom tray. The custom tray for applying these gels is made in the dental office. The patient is typically instructed to use the tray at bedtime on a daily basis. A small amount of brush-on gel is placed in the tray and the tray is placed over the teeth for five minutes. If water in the area is fluoridated, the patient is instructed to rinse and spit, preventing ingestion of excess fluoride. If the water is not fluoridated in the area, the patient is advised not to rinse after treatment.

Mouth rinses containing fluoride are another way of providing fluorides to those in areas without fluoridated water. Over the counter non-prescription rinses generally contain 0.05 percent sodium fluoride (NaF) and used daily. Prescription rinses generally contain 0.2 percent so dium fluoride and are used once a week. Toothpastes containing fluoride are an important ongoing source of topical fluorides – today most contain fluoride. A major benefit of these fluorides is the brushing action that brings fluoride into close contact with all surfaces of the teeth.

As a dental professional working with patients of all ages, you can offer the following advice for preventing eating disorders:

- Discourage restrictive dieting, meal skipping and fasting by correcting misconceptions about nutrition, normal body weight, and approaches to weight loss when a patient asks.

- Provide information about normal changes that occur during puberty if a patient has concerns or questions.

- Educate about the oral effects of purging. Many individuals probably don’t know the effects that stomach acid can have on the oral cavity such as ditched amalgams, enamel erosion, overall sensitivity, irregular incisal edges, and possible tooth discoloration.

- For individuals with tooth sensitivity, toothpastes formulated for sensitivity or commercially available desensitizing agents should be recommended.

If you have patients that you suspect have an eating disorder, or admit to having one, you can offer the following suggestions for care of their oral cavity:

- Wait 30 minutes after purging before brushing. This allows the saliva to remineralize the enamel. Rinse with sodium bicarbonate after purging.

- Use a fluoride rinse before going to sleep to help protect the teeth at night when salivary flow decreases.

- Limit intake of acidic beverages in the diet. Each time an acidic beverage is consumed, the pH in the oral cavity is lowered, giving the bacteria present the energy to decalcify the already damaged enamel structures of the teeth. Avoidance of sticky, sweet foods between meals should also be recommended because of the potential for additional decalcification and caries.

- Encourage the patient to suck on sugar-free chewing gum or sugar-free hard candy to stimulate saliva flow and remineralization of the enamel.

SUMMARY

The dental team’s involvement in the treatment, or even diagnosis of a patient’s eating disorder can vary. In the cases where a disorder is suspected, recognizing some of the warning signs or classic oral cavity symptoms is crucial for early intervention by referring to a healthcare provider such as a psychologist or eating disorder specialist. You may have a patient be referred to your clinic for the end phase of their treatment in which restorative procedures are performed to establish the patient’s oral cavity back to optimal health. The importance of understanding the etiology of the various disorders can help you better understand the patients you serve.

GLOSSARY

acidosis – an increase in the acidity of blood due to an accumulation of acids or an excessive loss of bicarbonate; the hydrogen ion concentration of the fluid is increased, lowering the pH

adolescent – young male or female not fully grown

alkalosis – increase in blood alkalinity due to a reduction of acids

allied dental professionals – individual who has received specialized dental training; a dental assistant, dental hygienist

amenorrhea – absence or suppression of at least three consecutive menstrual cycles when they are otherwise expected to occur

anemia – reduction in the number of circulating red blood cells

BUN – blood urea nitrogen; the metabolic product of the breakdown of amino acids for energy production

cibophobia – morbid aversion, or fear of, food

congenital – present at birth

dehydration – excessive loss of body fluid

dipsophobia – morbid fear of drinking

edema – local or generalized condition in which the tissues contain excessive fluid

emaciated – to become extremely thin, often as a result of starvation

erythrocyte – red blood cell

etiology – cause of a disease

extrovert – outgoing personality

geophasia – abnormal craving to eat earth substances like clay, sand, soil

geumatophobia – abnormal dislike or fear of tastes

glomerular filtration rate – step in the formation of urine in the kidney

hyperaldosteronism – excessive production of aldosterone by the adrenal gland

hypochloremic – deficiency of the chlorine content in the blood

hypoglycemia – low blood sugar

hypokalemia – extreme potassium depletion in the circulating blood, commonly manifested by episodes of muscle weakness or paralysis

hypothalamic – pertaining to the hypothalamus in the brain; the hypothalamus contains neurosecretions important for metabolic activities

hypothesized – assumed

interpersonal – involving relations between persons

kilocalories – equivalent to 1000 calories

lanugo – downy hair covering the body

leukocyte –white blood cell

Mallory Weiss lesions – Bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract due to a tear in the tissue lining of the esophagus or the junction of the esophagus and stomach

manifestations – sign or symptom of a disease

menses –monthly flow of bloody fluid from the endometrium

metabolism – the physical and chemical changes that take place within an organism

multifactorial – result of many factors

nonnutritive – having no nutritional value, usually inedible items

orthostatic hypotension – low blood pressure when moving from a supine to an upright position

osteoarthritis – arthritis marked by cartilage deterioration

osteoporosis – general term describing any disease process that results in the loss of bone mass

perforations – tear or rupture of the tissue or lining

perpetuate – cause to be continued indefinitely

phagophobia – fear of eating

platelet – component of blood that aids in coagulation of the blood

predispose – susceptibility to disease

prognosis – prediction of the course and end of a disease

QT syndrome – ventricles of the heart are unable to properly repolarize and recover

satiation – being full to satisfaction

sitophobia – psychoneurotic abhorrence of food, in general or to specific dishes

somatization – process of expressing a mental condition as a disturbed bodily function

substrates – substance acted upon by an enzyme

supraventricular dysrhythmias – abnormal heart rhythm originating above the ventricle

transaminases – enzymes that begin the transfer of the amidine group from one amino acid to another

tryptophan – essential amino acid found in high concentration in animal and fish protein; needed for growth and development

ulcerations – sores or lesions on mucous membranes and tissues such as the skin

ventricular dysrhythmias – abnormal heart rhythm originating in the ventricle

REFERENCES

1. Health and Public Policy Committee, American College of Physicians: Eating Disorder: Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia, Nutrition Today, March / April 1987page 29

2. Nicholi AM: The New Harvard Guide to Psychiatry, Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1989

3. Comerci GD: Medical Complications of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa, Medical Clinics of North America 74: 1293, 1990

4. Casper, RC et al: Total Daily Energy Expenditure and Activity Level in Anorexia Nervosa, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 53:1143, 1991

5. Mynors-Wallis LM: The Psychological Treatment of Eating Disorders, British Journal of Hospital Medicine 41:470, 1989

6. Omizo SA: Anorexia Nervosa: Psychological Considerations for Nutritional Counseling, Journal of the American Dietetic Association 88:49, 1988

7. Beresin EV et al: The Process of Recovering From Anorexia Nervosa; Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis 17:103, 1989

8. Patton G: The Course of Anorexia Nervosa, British Medical Journal 299:139; 1989

9. http://www.swedauk.org/disorders/other.htm, accessed Aug. 25, 2006

10. http://www.mental-disorder.net/wb/pages/eating-disorders/bulimia.php, accessed Sept. 3, 2006

11. Riley EA: Eating Disorders As An Addictive Behavior, Nursing Clinics of North America 26:715, 1991

12. Pugliese, MT et all: Fear of Obesity: A Cause of Short Stature and Delayed Puberty, The New England Journal of Medicine 26:715, 1991

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Bird D.L. and Robinson, D.S. (2012) Modern Dental Assisting. 10th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders

Eating Disorder Statistics. http://www.statisticbrain.com/eating-disorder-statistics/. Accessed May 2013.

http://www.journalsonline.tandf.co.uk/openurl.asp?genre=journal&issn=1064-0266, Eating Disorders, accessed Aug. 2006

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/14710153, Eating Behaviors, accessed Sept. 2006

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, www.ANAND.org. Accessed May 2013

Position of the American Dietetic Association: Nutrition Intervention in the Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified, Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2001 July; 101(7), pp. 810-819

Smolak L. (2011). Body image development in childhood. In T. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Wade TD, Keski-Rahkonen A, Hudson J. (2011). Epidemiology of eating disorders. In M. Tsuang and M. Tohen (Eds.), Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology (3rd ed.) (pp. 343-360). New York: Wiley.

www.mentalhealthscreening.org (National Eating Disorder Screening Program), accessed Aug. 2006

www.nationaleatingdisorders.org (National Eating Disorders Association), accessed Sept. 2006

Yagi T, Ueda H, Amitani H, Asakawa A, Miyawaki S, and Inui A. *The Role of Ghrelin, Salivary Secretions, and Dental Care in Eating Disorders. Nutrients. 2012 August; 4(8): 967–989.

APPENDIX 1

Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

Anorexia Nervosa

- Refusal to maintain body weight over a minimal normal weight forage and height

- Weight loss leading to maintenance of body weight 15% below that expected

- Failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight 15% below that expected

- Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight

- Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight, size or shape is experienced. The person claims to feel fat even when emaciated, believes that one area of the body is too fat even when obviously underweight

- In females, absence of at least three consecutive menstrual cycles when otherwise expected to occur

Bulimia Nervosa

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating (rapid consumption of a large amount of food in a discrete period of time

- A feeling of lack of control overeating behavior during the eating binges

- The person regularly engages in either self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics, strict dieting or fasting, or vigorous exercise to prevent weight gain

- A minimum of two binge eating episodes per week for at least three months

- Persistent over concern with body shape and weight

From The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III-R).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Natalie Kaweckyj, LDARF, CDA, CDPMA, COMSA, MADAA, BA

Natalie Kaweckyj currently resides in Minneapolis, MN, where she is the Clinic Coordinator and Compliance Analyst for a nonprofit pediatric dental clinic. She is a Licensed Dental Assistant in Restorative Functions (LDARF), Certified Dental Assistant (CDA), Certified Dental Practice Management Administrator, Certified Orthodontic Assistant, Certified Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery Assistant, and a Master of the American Dental Assistants Association. She holds several expanded function certificates, including the administration of nitrous oxide/oxygen analgesia. Ms. Kaweckyj graduated from the American Dental Association-accredited dental assisting program at ConCorde Career Institute and has received a Bachelor of Arts in Biology and Psychology from Metropolitan State University. She is currently writing her dissertation for her master’s in Public Health. She has worked clinically, administratively and academically. Ms. Kaweckyj is currently serving as ADAA President Elect, and has served on the ADAA Board of Trustees since 2002.She is current legislative chairman for the Minnesota Dental Assistants Association (MDAA) and three time past president of MDAA. She also just concluded her term as President of the Minnesota Educators of Dental Assistants. In addition to her association duties, Natalie is very involved with the Minnesota state board of dentistry as well as with state legislature in the expansion of the dental assisting profession. She is a freelance writer and lecturer and is always working on some project. She has authored many other courses for the ADAA.