You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

GLOSSARY

PATIENT DATA

The administrative team must be familiar with the terms used in documentation in the patient’s clinical record and be able to interpret notations made within the clinical record as this knowledge aids in overall patient treatment. The dentist is responsible for diagnosis and treatment of the patient, but the dental team should always be alert for abnormal conditions in all patients’ oral cavities. The administrative assistant will assist in processing documentation to other parties involved in the complete care of the patient.

The clinical record will include the following:

• Patient folder is what holds the contents of the clinical record together. In a paperless office (one that is completely computerized), the patient folder is often omitted.

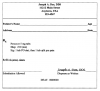

• Patient registration form (Figure 1) is the initial form the patient fills out prior to the first appointment. Listed on this form are legal name, birth date and age, residence and work contact information that includes home and billing addresses, insurance information and responsible party information, physician’s name and phone number, and emergency contact name and number.

• Medical/dental history questionnaire and update forms list questions and conditions the patient is currently experiencing or may have experienced in the past. Often, the medical history portion of the questionnaire will list a medical condition prompting the patient to write the name of medication they may be taking at the time of the appointment. This form is reviewed at every visit and updated with the date and patient’s signature or initials. Allergies or sensitivities to certain medications and substances are also noted here. The dental questionnaires also normally inquire about the name and phone number of the previous dentist.

• HIPAA acknowledgment form must be signed by the patient stating that they have received the dental practice’s policy on patient information protection. If the patient should choose to decline acceptance of the policy, a blank form must be signed with a notation and date that the patient refused.

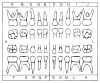

• Clinical chart refers to the charting of oral conditions; includes periodontal charting and charting of restorations and areas in need of treatment. Clinical charting may be done on a graphic chart either manually or by using computer software (Figure 2) specifically designed for charting clinical conditions at chairside. Special codes are used to differentiate between different types of restorations and oral conditions that exist in the patient’s mouth (Figure 3). There are many types of charting designs for charting or oral conditions, the two most common being diagrammatic and geometric. Diagrammatic charts show the crown and roots of teeth, whereas geometric charts have circles divided to represent each surface of the tooth. Treatment record/progress notes refers to the page(s) in the record that the clinical provider makes notations on. In some practices, this is referred to as the “services rendered” sheet. All treatment notations are made in ink. (See section on SOAP Format).

• Diagnosis, treatment plan, and estimate sheet lists the diagnosis of the condition, treatment plan options, and an estimated cost of each treatment option. A copy is often given to the patient.

• Radiographs for the entire length of the patient history are kept in the clinical record. In some specialty offices, such as an orthodontic practice, radiographs such as a cephalograph may be kept in a different location because of the size of the radiograph.

• Consultation and referral reports are kept as they pertain to direct patient treatment. Many practices keep these reports to the back of the patient record.

• Consent forms are kept on file in the clinical record as record of patient agreement for treatment.

• Medication history and prescription forms are a crucial component of the clinical record. Any time a medication is prescribed to a patient, it is noted with the progress notes. Some practices do keep copies of the patient prescription, while others use a stamped template in their progress notes.

• Letters/postal receipts or any other correspondence are kept from patients and attorneys, along with registered mail receipts.

• Copies of laboratory tests are kept with the patient record with a notation made in the progress notes of when the patient was referred for testing, the date, and the prognosis of the tests.

The administrative team usually maintains these records and should be familiar with the content and terminology noted on these documents. You may need to refer to other sources such as a clinical dental assistant textbook or a medical/dental dictionary to familiarize yourself with terms you do not know.

S—refers to subjective, the purpose of the patient’s dental visit. This section also includes the description of symptoms in the patient’s own words including: pain, what triggers the discomfort, what causes the discomfort to disappear, and the length of time these symptoms have been occurring.

O—refers to objective, unbiased observations by the dental team. Included under this heading would be things that can actually be felt, heard, measured, seen, smelled, and touched.

A—refers to assessment, the diagnosis of the patient’s condition done by the dentist. The diagnosis may be clear or there may be several diagnostic possibilities.

P—refers to the plan or proposed treatment, and is decided upon by the patient and the dentist. The plan may include radiographs, medications prescribed, dental procedures, patient referral to specialists, and patient follow-up care instructions.

A SOAP notation is not supposed to be as detailed as a progress report and the use of abbreviations is standard. Abbreviations will vary slightly from one practice to another, so it is important to use notations commonly used within the practice. It is imperative that the individual making the notation sign their name and list their credentials so that those reading the record know who was responsible for the notes. Notes should be free from scribbles and whiteout errors. If an error is made, a single line should be drawn through the error, dated, and initialed, and the correction written. Corrections in computerized formats will vary according to dental software. Notations should be written fluently and without blank lines between the entries. This will prevent additional information being added without the writer’s knowledge.

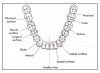

Arches: The teeth in the oral cavity are arranged in two separate arches. The upper teeth are located in the maxillary arch; the lower teeth are located in the mandibular arch. The maxillary arch is fixed and larger so it overlaps the mandibular arch vertically and horizontally, while the mandibular arch is capable of movement. The teeth are normally arranged in the maxillary and mandibular arches in such a way that they will function properly and the position of each tooth is maintained.

Quadrants: Each arch can then be divided in half by an imaginary vertical line drawn through the center of the face, or midline. Each of these halves of the arch is called a quadrant. The four quadrants are maxillary right, maxillary left, mandibular right, and mandibular left. The quadrants are labeled according to the patient’s right or left. When the dental team looks at a patient’s face, the directions of right and left are reversed. The arrangement and classification of teeth in each quadrant is identical.

Dentitions: There are three types of dentitions in the oral cavity throughout our lifetimes. At birth, there are 44 teeth, in various stages of development, within the maxillary and mandibular jaws. As the child matures, primary teeth begin to erupt. Primary teeth are also referred to as deciduous teeth by the dental profession. You may hear your patients refer to them as milk teeth or baby teeth. Permanent teeth that replace primary teeth are called succedaneous teeth. The only permanent teeth not called succedaneous are the molars. The primary teeth function in several ways during childhood:

• Provide chewing surface in relationship to size of mouth

• Aid in speech

• Act as a guide for permanent teeth

• Promote positive self-image

All primary teeth typically should be in occlusion shortly after age 2, while the roots of the primary teeth are fully formed by age 3. There are 20 teeth in a complete primary dentition, five in each quadrant (Figure 4). All classifications of teeth are represented within the primary dentition except for the premolars. Between the ages of 4 and 5, the two upper front teeth begin to separate due to the growth of the jaw and the approach of the permanent teeth.

The actual shedding, or exfoliation, of the primary teeth takes place between ages 5 and 12. During these years, the child is in a mixed dentition stage—there are both permanent and primary teeth within the oral cavity (Figure 5). It is during this stage that developing anomalies often take place and preventative orthodontics is started on patients when needed.

Tooth exfoliation is caused by the resorption of the roots of the primary teeth by the bone-resorbing cells called osteoclasts. This resorption normally begins within a year or two after root formation is complete. It begins at the apex, or tip of the root, and will continue in the direction of the crown of the tooth. Primary anteriors, or front teeth, are resorbed on the inside surface called the lingual surface. Primary molars are resorbed on the inside root surface.

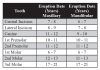

Permanent dentition usually consists of 32 teeth, eight teeth in each quadrant. Eruption patterns vary from child to child (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

There are several differences between the primary and permanent dentitions. Primary teeth are smaller with thinner enamel, the pulp chamber is larger, and the teeth appear short and squat. The primary roots tend to flair more with shorter molar root trunks. Some individuals can retain a primary tooth because of the absence of a permanent tooth underneath the primary tooth. The most common missing permanent teeth are the mandibular secondary premolar, the maxillary lateral incisor, and mandibular central incisors.

TEETH

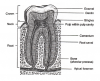

Enamel forms the outermost surface of the crown of the tooth and is the hardest tissue in the body, therefore making it an ideal protective covering for a tooth. Even though the enamel is hard, it is also the most brittle under certain conditions. Composed of 96% inorganic and 4% organic materials, and therefore unable to register pain stimuli, enamel can withstand chewing forces of up to 100,000 psi. The strength of enamel, along with the cushioning effect of dentin and periodontal ligament, help protect the tooth.

Once enamel is completely formed, it does not have the capability for further growth or to repair damaged areas, but it does have the ability to restore itself through a process called remineralization. Areas in the enamel can lose minerals due to the acidity produced in bacterial by-products within the plaque. These weakened areas are able to regain minerals through the process of remineralization.

The second hardest tissue in the body is dentin, composed of 70% organic and 30% inorganic materials. Although dentin is a hard tissue, it does have elastic properties that support the enamel layer above it. Dentin includes the main portion of the tooth and is made up of microscopic passages called dentinal tubules. These tubules transmit pain stimuli and nutrition throughout this layer of the tooth.

There are three types of dentin found in a human tooth. The dentin that forms when a tooth erupts is called primary dentin and, unlike enamel, dentin does have the capability for additional growth. The dentin that forms inside the primary dentin is called secondary dentin. This type of dentin continues to grow throughout the life of the tooth. The third type of dentin, called reparative dentin, is formed as a response to attrition, erosion, or some irritation, such as a bacterial or chemical invasion of its surface.

Cementum is the third type of hard tissue that covers the root of the tooth in a very thin layer. It is not as hard as enamel or dentin, but it is harder than bone with a similar composition of 50% organic and 50% inorganic materials. It contains fibers that help to anchor the tooth within the bone. Cementum is light yellow in color, lighter than dentin, and easily distinguishable from enamel because it lacks shine.

There are two types of cementum. Primary cementum, also known as acellular cementum, covers the entire length of the root and does not have additional growth ability. Secondary cementum, also known as cellular cementum, forms after the tooth has reached functional occlusion and continues throughout the life of the tooth at the apical third of the tooth. Secondary cementum is able to continue to grow because it contains specialized cells called cementoblasts that continue producing cementum as needed to maintain the tooth in functional occlusion when enamel is lost to attrition.

The last type of tissue is the pulp, which is located in the center of the tooth. The pulp is composed of blood vessels, lymph vessels, connective tissue, nerve tissue, and cells called odontoblasts, which are able to produce dentin. The pulp cavity is divided into two areas: the pulp chamber, located in the crown of the tooth, and the pulp canal(s), located in the root(s) of the tooth. When teeth first erupt, the pulp chamber and canal(s) are large, but as secondary dentin forms they decrease in size.

Because these surface names would take up a great deal of space in a chart, they are abbreviated. Single surfaces are abbreviated as follows:

When two or more surfaces are involved, the names are combined. To combine the surface names, the “al” ending of the first surface is substituted with the letter “o.” Abbreviations for combinations of surfaces are as follows:

Types of Teeth

As well as aiding in the chewing and digestion processes, teeth have several other functions. Teeth protect the oral cavity, aid in proper speech, and affect the physical appearance and self-esteem of an individual.

Humans have two main types of teeth, with subdivisions within each of the categories. The front six teeth on both the lower and upper arches are called the anterior teeth and are all single-rooted teeth. Four of these teeth in each arch are called incisors, while the two remaining are called canines. The premolars and molars are called posterior teeth because they are located in the back of the oral cavity and make up the five most posterior teeth in each quadrant of the mouth. There are two types of premolars and three types of molars included in the posterior classification (Figure 10).

Maxillary/Mandibular Lateral Incisors: On either side of the maxillary central incisors is the lateral incisor just distal of the central incisor. Typical characteristics of maxillary lateral incisors include a straight, sharp, cutting incisal edge, rounded mesial–incisal and distal–incisal corners, and a small cingulum on the lingual. Less common, these teeth can be dwarf-sized, peg lateral in shape, or congenitally missing. The maxillary lateral incisor is, overall, smaller in size and shape than the maxillary central incisor. Typical characteristics of mandibular lateral incisors include a rounded distal–incisal edge and a mesial–incisal edge that forms a 90° angle. The mandibular lateral incisor is overall larger, wider, and longer than the mandibular central incisor.

Maxillary/Mandibular Canines: On each side of the lateral incisors, forming the cornerstone of the mouth, are the canines, or cuspids as they are sometimes called. The two maxillary canines have one cusp, or pointed edge, and are used for holding or grasping food. The maxillary canines are very strong, the most stable in the mouth, and therefore usually the last ones to be lost due to disease. The mandibular canines are not quite as prominent as the maxillary canines and have lesser-defined anatomy. Canines are sometimes referred to as “eye teeth” in layman terms.

Maxillary/Mandibular First Premolar: The maxillary premolars all have two cusps, a buccal and a lingual cusp. The first premolar can have two separate roots, one root fused together with two canals or a single root that splits at the apical third of the root. The mandibular first premolar also has two cusps, a buccal and a lingual, but the lingual cusp is so small that it is considered non-functional. The mandibular first premolars always only have one root. The first premolars throughout the dentition tend to be weaker than the second premolars and are often sacrificed during orthodontic treatment when space is needed.

Maxillary/Mandibular Second Premolar: The maxillary second premolars have two cusps and one root. The cusps are equal in height, but the overall size of the crown is smaller than that of the maxillary first premolar. The mandibular second premolar has one root that is larger and longer than the mandibular first premolar, and has three cusps—a buccal, a mesiolingual, and a distolingual.

Maxillary/Mandibular First Molar: The maxillary and mandibular first molars have multiple cusps. These permanent teeth come in around age 6 and are therefore given the name “6-year molars.” The maxillary molars have four functional cusps, a fifth non-functional cusp, called the cusp of Carabelli, and three roots. The mandibular molars in this group also have five fully functional cusps, but typically only two roots that are very straight. They are the largest of the mandibular teeth and the first of the mandibular permanent teeth to erupt.

Maxillary/Mandibular Second Molar: The maxillary and mandibular permanent molars come in around age 12 and therefore often called the “12-year molars.” The maxillary and mandibular molars of this group have four cusps, three and two roots respectively, and are overall smaller in size than both first molars.

Maxillary/Mandibular Third Molar: The third molars are the most variable in size, shape, and eruption times of all of the teeth in the permanent dentition. Third molars typically erupt in the late teens or early adulthood and are commonly referred to as “wisdom teeth.” The maxillary third molars typically have three or four roots and are frequently fused together and impacted in the bone of the jaw. The mandibular third molars tend to have two roots, four to five cusps, and a wrinkled appearance to the occlusal surface. Both types of teeth are irregular and unpredictable.

Occlusion is defined as the contact between the maxillary and mandibular teeth in any functional relationship. Normal occlusion is important for optimal oral functions such as chewing, speaking, swallowing, preventing dental diseases, and also for esthetics. Any deviation from normal occlusion is considered as malocclusion. Malocclusion may involve a variety of scenarios: a single tooth, groups of teeth or entire arches may be involved. Malocclusion may be caused by several factors including genetics, diseases that disturb dental development, injuries, and oral habits such as thumb-sucking or tongue-thrusting.

Classifications of Occlusion

Angle’s classification system is a method commonly used to classify various occlusal relationships. This system is based upon the relationship between the permanent maxillary and mandibular first molars.

Class I (or neutrocclusion): In this classification, the maxillary first molar is slightly back to the mandibular first molar; the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar is directly in line with the buccal groove of the permanent mandibular first molar. The maxillary canine occludes with the distal half of the mandibular canine and the mesial half of the mandibular first premolar. The facial profile is termed mesognathic.

Class II (or distocclusion): In this classification, the maxillary first molar is even with, or anterior to, the mandibular first molar; the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar is distal to the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar. The distal surface of the mandibular canine is distal to the mesial surface of the maxillary canine by at least the width of a premolar. The facial profile of both divisions is termed retrognathic.

Class II, Division 1 occurs when the permanent first molars are in Class II and the permanent maxillary central incisors are either normal or slightly protruded out toward the lips.

Class II, Division 2 occurs when the permanent first molars are in Class II and the permanent maxillary central incisors are retruded (pulled backward toward the oral cavity) and tilting inwards toward the tongue.

Class III (or mesiocclusion): In this classification, the maxillary first molar is more to the back of the mandibular first molar than normal; the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar is mesial to the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar. The facial profile is termed prognathic.

There are several deviations in the position of the individual teeth within the jaws. The following terms describes these variations:

• Anterior cross-bite: an abnormal relationship of a tooth or a group of teeth in one arch to the opposing teeth in the other arch; the maxillary incisors are lingual to the opposing mandibular incisors

• Distoversion: the tooth is distal to the normal position

• Edge-to-edge bite: the incisal surfaces of the maxillary anterior teeth meet the incisal edges of the mandibular anterior teeth

• End-to-end bite: maxillary posterior teeth meet the mandibular posterior teeth cusp-to-cusp instead of in normal manner

• Infraversion: the tooth is positioned below the normal line of occlusion

• Labioversion (buccoversion): the tooth is tipped toward the cheek or lip

• Linguoversion: the tooth is lingual to the normal position

• Mesioversion: the tooth is mesial to the normal position

• Open bite: failure of the maxillary and mandibular teeth to meet

• Overbite: vertical overlap greater than one third vertical extension of the maxillary teeth over the mandibular anterior teeth

• Overjet: the horizontal overlap between the labial surface of the mandibular anterior teeth and the lingual surface of the maxillary anterior teeth, causing and abnormal distance

• Posterior cross-bite: an abnormal relationship of teeth in one arch to the opposing teeth in the other arch. The primary or permanent maxillary teeth are lingual to the mandibular teeth

• Supraversion: the tooth extends above the normal line of occlusion

• Torsoversion: the tooth is rotated or turned

• Transversion (transposition): the tooth is in the wrong order in the arch

• Underjet: occurs when the maxillary anteriors are positioned lingually to the mandibular anteriors with excessive space between the labial of the maxillary anterior teeth and the lingual of the mandibular anterior teeth

Patient Charting

Numbering Systems

Universal Numbering Systems

The primary dentition lettering begins with the maxillary right second molar as letter A and continues clockwise to the maxillary left second molar as letter J; the mandibular left second molar is letter K, and the mandibular right second molar is letter T (Figure 14).

Quadrants with permanent dentition are given a number beginning with the upper right—1, upper left—2, lower left—3 and lower right—4. In the primary dentition, the numbers 5-8 are used for the corresponding quadrants. Each permanent quadrant is numbered 1–8 starting with the central incisor and ending with the molars. The primary teeth are numbered 1–5 in a similar method. In using the FDI system, the quadrant number is recorded first followed by the tooth number. For example, the mandibular right first molar in the permanent dentition is noted as 46 and in the primary dentition as 84. When verbally reading the two-digit notation, each number is read separately; 23 would be read as “two, three” (Figure 15).

Charting Colors and Symbols

Figure 16 Charting

Amalgams:

#2: MOD Amalgam

#3: MO Amalgam & B Amalgam with Recurrent Caries

#4: O Amalgam

#5: O Caries

Composites:

#10: MIFL Caries

#11: D Composite

#12: MOD Composite

Crowns:

#18: Full Gold or HNM Crown

#19: MOD Gold or HNM Inlay

#27: Porcelain Crown

#29: Needs Porcelain-Fused-to-Metal Crown

#30: Ceramic Onlay (CEREC)

Figure 17 Charting Existing Conditions

Tooth No. 1 is missing (charted in blue) with retained root tip (charted in red)

Tooth No. 2 existing MOD amalgam (charted in blue) with mesial overhang (charted in red)

Tooth No. 3 gingival recession with furcation involvement (charted in red)

Tooth No. 4 existing PFM crown (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 5 existing sealant (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 6 existing implant (charted in blue) needs porcelain-fused-to-HNM crown (charted in red)

Tooth No. 7 existing DF composite (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 8 has a MI fracture or MI caries (charted in red)

Tooth No. 9 has an all-ceramic or all-porcelain crown (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 10 has a DI composite (charted in blue)

Between tooth Nos. 11 & 12 there is an open contact or diastema (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 11 is sound

Tooth No. 12 existing DO amalgam with recurrent caries (charted in blue, outlined in red)

Tooth No. 13 has MOD caries, composite treatment planned (charted in red)

Tooth No. 14 existing porcelain-fused-to-HNM crown three-unit bridge (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 15 existing HNM crown (pontic) three-unit bridge (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 16 existing HNM crown (abutment) three-unit bridge (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 17 fully erupted, to be extracted (charted in red)

Tooth No. 18 existing stainless steel crown (charted in blue)

Between Teeth No. 18 & 19: food impaction (charted in red)

Tooth No. 19 existing MODFL amalgam (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 20 endontontically treated with post and core (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 21 rotated to the distal (charted in red)

Tooth No. 22 existing lingual amalgam (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 23 existing porcelain veneer (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 24 existing retainer for Maryland bridge (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 25 existing Maryland pontic (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 26 existing retainer for Maryland bridge (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 27 existing F composite (charted in blue)

Teeth Nos. 27 through 30, existing lingual tori (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 28 is sound

Tooth No. 29 existing periapical abscess; tooth is extruded (charted in red)

Tooth No. 30 needs an occlusal sealant; tooth has drifted medially; has class V buccal caries (charted in red)

Tooth No. 31 is missing (charted in blue)

Tooth No. 32 is impacted and horizontal (charted in red)

Amalgam

Composite

Gold or High Noble Metal (HNM)

Porcelain

Symbols and abbreviations may vary slightly from one office to another. It is important to become familiar with these symbols, as you may be called upon to assist the clinical team in charting.

Recording on the Patient Chart

The dentist must ensure that all dental records are accurate and reflect up-to-date information on each patient within the practice. The clinical team will be responsible for clinical notes. The administrative team may also need to document communication with patients in certain instances. All notations must be written in ink and be legible. When initials are used, the practice must have on hand a list of team members’ names and initials should there ever be a question of who made a certain notation. As previously mentioned, any corrections should be made by drawing a single line through the incorrect portion, initialing the correction and dating the new information.

Computerized Clinical Charting

Using computer software specifically designed for charting clinical conditions in the treatment area is called computerized clinical charting (Figure 18). Particular codes are used to distinguish between different types of restorations and oral conditions that exist in the patient’s mouth. The administrative team member may not perform this task routinely in the treatment area, but it is beneficial to learn all of the codes to be able to communicate conditions to the patient and reasons to schedule future appointments.

Documentation

Use of Digital Imaging

Dentists use imaging systems frequently these days in dentistry. Some of the types of imaging dentists may use include:

• CT scanning (computed tomography) to plan implant surgery, to draw orthodontic tracings, and to locate and define lesions associated with the oral cavity.

• MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) to diagnose temporomandibular joint disease and injuries to the head and face.

• Digital radiography (computed dental radiography) to allow the dentist to take an intraoral x-ray, then process and show the image on the computer screen. In addition you will find computer imaging used as a tool in cosmetic imaging, as well as construction of prosthetic devices.

Documenting Treatment

Each dental provider is responsible for documenting treatment provided to his or her patients. Some states allow the dental assistant to make the clinical notes, which the supervising dentist reviews and then initials the entry. Dental hygienists typically write their own treatment notes within the patient record. At times, the administrative staff will need to add a missed entry when updating records or when additional information is brought forth after the appointment time. It is best to verify with the dentist the best way to handle these situations.

Documenting Prescriptions

From time to time, the administrative staff may be involved with the documentation of drug prescriptions. A prescription is a written instruction by the dentist that directs the pharmacist to dispense a drug that by law can only be sold by prescription. In the dental office, the dentist is the only person qualified to prescribe drugs. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regulate all prescription medications. The FDA establishes which drugs can be marketed in the United States and which drugs require a prescription for purchase. The FDA also regulates the labeling and advertising of these drugs. The FTC regulates the trade practices of drug companies and the advertising of foods, nonprescription drugs and cosmetics. The DEA regulates the production and distribution of substances that have a potential for abuse.

The dentist will receive a DEA identification number once he/she is authorized to prescribe drugs. If a patient is given a written prescription for a medication it must be documented, either by placing a copy of the prescription in the record or by writing all details in the clinical record. In many states, a dental assistant, dental hygienist nor any of the administrative team is allowed to phone in a prescription to the pharmacy. Please consult your state’s Dental Practice Act.

When the dentist phones in a prescription it must be documented in the patient’s record. Some dental practices that are paperless are able to print the required prescription from the computer in the treatment room. Most prescriptions can be phoned in. A written prescription is required for narcotics. Prescription pads should be stored in a secured location to prevent their theft.

Common Prescription Abbreviations

Frequently, abbreviations are used when a prescription is written out for a patient. These abbreviations save time, space and make it more difficult for a patient to alter a prescription. All prescriptions should be written clearly on the prescription form. (Appendix A shows a list of some commonly used abbreviations.)

In some instances, the dental team members may prepare a prescription for the dentist’s signature, but the dentist must always check it and place his/her signature on it after verifying that it is correct. The format of some prescriptions may vary slightly but they should all contain the same information. A prescription is made up of a heading, a body and a closing (Figure 19).

The heading consists of the date; the dentist’s name, address, and telephone number; and the patient’s name, address, and age.

The body of the prescription follows the symbol “Rx” and contains the name of the drug, the dosage size or concentration (strength), the dose form (eg, tablets) and the amount to be dispensed. When a controlled substance is prescribed, the amount to be dispensed should be written out in words after the number to prevent illegal altering of the prescription. The body also includes directions for the patient on how to take the drug. These directions should be easily understandable and should include the medication amount, time to be taken, frequency, and route of administration.

The closing of the prescription is where the dentist will sign the prescription and give instructions on whether or not a generic substitution may be made (Figure 20). Drugs have a brand name, also known as a trade name, and a generic name. The brand name is the name given to a drug by a pharmaceutical company after it has researched the drug and found that it is useful. It is the property of the company registering the drug and is registered as a trademark. The generic name of a drug is the official name of the drug. There is only one generic name for each drug, and the name is not capitalized when it is written.

The closing area also includes refill instructions. The number of refills should be written out in words after the number, again to avoid illegal altering of the prescription. If no refills will be allowed, this should be clearly written out in words as well.

There should also be a place in which to write the prescribing doctor’s DEA number. This number must be written on all prescriptions for controlled substances. It is usually best if this number is not preprinted on the prescription so that in the case that the prescription pad is stolen from the practice, the thief will not be able to forge a prescription for a controlled substance. Over the years the government has developed laws that are designed to regulate the production, distribution, and sale of drugs. One of these laws, the Controlled Substance Act of 1970, regulates drugs that have the potential for abuse. The drugs are divided into five schedules based on their potential for abuse and physical and psychological dependence. The DEA is responsible for the enforcement of this Act. Drugs are constantly being evaluated and added to the schedule, or moved from one schedule to another.

Documenting Instructions

In addition to treatment and prescriptions, documentation of preoperative and postoperative instructions is included in the patient record. Preoperative instructions may include what the patient is to do prior to a particular dental appointment, such as refraining from eating 6 to 8 hours prior to a surgical procedure in which general anesthesia will be used. Postoperative instructions can include variations to regular brushing and flossing, foods to avoid for a specified time and what the patient can expect as far as signs and symptoms of discomfort. Having everything documented not only protects the practice from a legal standpoint, but also makes it convenient should the patient call before or after their appointment in question.

HIPAA

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requires that the transactions of all patient healthcare information be designed in a standardized electronic style. In addition to protecting the privacy and security of patient information, HIPAA includes legislation on the formation of health savings accounts (HSAs), the authorization of a fraud and abuse control program, the easy transport of health insurance coverage and the simplification of administrative terms and conditions.

HIPAA privacy requirements can be broken down into three types: privacy standards, patients’ rights, and administrative requirements.

Privacy Standards

A fundamental concern of HIPAA is the careful use and disclosure of protected health information (PHI). PHI is commonly electronically controlled health information that can be recognized individually, typically through the use of Social Security numbers or other individually designated identifiers. PHI also refers to verbal communication, although the HIPAA Privacy Rule is not intended to obstruct necessary verbal communication. The United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) does not require restructuring of the dental practice, such as soundproofing, architectural changes, and so forth, but some caution is necessary when exchanging health information by conversation.

An Acknowledgment of Receipt Notice of Privacy Practices, which allows patient information to be used or divulged for healthcare treatment, payment or operations (TPO), should be obtained from each patient. The patient must sign a statement acknowledging receipt of the practice’s written privacy policy and is kept in the patient’s record for a minimum of 6 years. A detailed and time sensitive authorization can also be issued, which allows the dentist to release information in special circumstances other than TPOs. A written consent is also an option. Dentists can disclose PHI without acknowledgment, consent, or authorization in very special situations such as any of the following:

• Fraud investigation

• Law enforcement with valid permission (ie, a warrant)

• Perceived child abuse

• Public health supervision

When divulging PHI, a dentist must try to disclose only the minimum necessary information to help safeguard the patient’s information as much as possible. It is important that dental professionals adhere to HIPAA standards because healthcare providers (as well as healthcare clearinghouses and healthcare plans) who convey electronically formatted health information via an outside billing service or merchants, are considered covered entities. Covered entities may be dealt serious civil and criminal penalties for violation of HIPAA legislation. Failure to comply with HIPAA privacy requirements may result in civil penalties of up to $100 per offense with an annual maximum of $25,000 for repeated failure to comply with the same requirement. Criminal penalties resulting from the illegal mishandling of private health information can range from $50,000 and/or 1 year in prison to $250,000 and/or 10 years in prison.

Patient Rights

HIPAA allows patients, authorized representatives and parents of minors, as well as minors, to become more aware of the health information privacy to which they are entitled. If any health information is released for any reason other than TPO, the patient is entitled to an account of the transaction. Therefore, it is important for dentists to keep accurate records of such information and to provide them when necessary.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule determines that the parents of a minor have access to their child’s health information. This privilege may be overruled, for example, in cases where there is suspected child abuse or the parent consents to a term of confidentiality between the dentist and the minor. The parents’ rights to access their child’s PHI also may be restricted in situations when a legal entity, such as a court, intervenes and when a law does not require a parent’s consent. A full list of patient rights are listed in the most current version of HIPAA Standards.

Administrative Requirements

Complying with HIPAA legislation may seem like a chore, but it does not need to be. It is recommended that you become appropriately familiar with the law, organize the requirements into simpler tasks, begin compliance early and document your compliance progress.

An important first step is to evaluate the current information and practices of your office. Dentists will need to write a privacy policy for their office, which is a document for their patients detailing the office’s practices concerning PHI. It is useful to try to understand the role of healthcare information for your patients and the ways in which they deal with the information while they are visiting your office. Staff training is a must. Make sure staff are familiar with the terms of HIPAA and the practice’s privacy policy and related forms. HIPAA requires that a privacy officer be designated. A privacy officer is a person in the practice who is responsible for applying the new policies in the practice, fielding complaints, and making choices involving the minimum necessary requirements. Another employee assigned the role of contact person will process complaints.

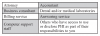

A Notice of Privacy Practices, a document detailing the patient’s rights and the dental practice’s obligations concerning PHI, also must be drawn up. Further, any role of a third party with access to PHI must be clearly documented. This third party is known as a business associate (BA) and is defined as any entity that, on behalf of the dentist, takes part in any activity that involves exposure or disclosure of PHI (Figure 21).

The following are not considered to be Business Associates: a member of the staff, such as an employed dental associate, assistant, receptionist or hygienist; the US Postal Service; or a janitorial service (Figure 22).

HIPAA Security

The final version of the HIPAA Security Rule was released in 2003 with a compliance date of April 20, 2005. The Security Rule defines highly detailed standards for the integrity, accessibility and confidentiality of electronic protected health information (EPHI) and addresses both external and internal security issues.

Entities covered by HIPAA are required to:

• Assess potential risks and vulnerabilities

• Protect against threats to information security or integrity, and guard against unauthorized use or disclosure of information

• Implement and maintain security measures that are appropriate to their needs, capabilities, and conditions

• Ensure entire staff compliance with these safeguards

The HIPAA Security Standard is broken into three separate parts:

Administrative Safeguards: This segment, which makes up half of the complete standard, limits information access to proper individuals and shields information from all others. It must include documented policies and procedures for daily operations; address the conduct and access of workforce members to EPHI; and describe the selection, development, and use of security controls in the workplace.

Physical Safeguards: Physical safeguards prevent unauthorized individuals from gaining access to EPHI via computerized systems and the Internet.

Technical Safeguards: This section includes using technology to protect and control assess to EPHI.

Records Management

The patient chart is a legal record of dental services. Information noted must be accurate, comprehensive, concise, and current.

Legal Aspects of the Patient Record

Legal aspects of the patient record include everything on the patient registration form. Most of the information in the dental record should be clinical in nature. It is imperative that this form is filled out completely and accurately. Without accurate and current information, the dental practice, namely the dentist, does not have legal backing should a lawsuit ensue.

When recording anything in the patient record, it is important that whoever is doing the documentation write the date first. Without a date, whatever is being documented never occurred. If it is a patient visit that is being documented, the next entry should make reference to updating the patient’s medical history. This is a step that must be done at every visit as conditions change and it is important that the team be aware of any changes so they may be serve their patient.

• When using the SOAP format for documentation, it is easy to remember what areas need to be documented. For practices that do not utilize this format, the next step would be to record the reason for the visit, listing the primary dental complaint as well as any other concerns the patient may have. Part of the standard of care is listening to the patient.

• Before beginning any treatment, a signed informed consent form should be obtained from the patient. Informed refusal forms should be obtained when a patient refuses a recommended treatment plan (for example, for radiographs, a dental examination or scaling and root planing) and should be documented on the patient record.

• Any diagnostic tests performed to derive a diagnosis must be documented. This may include any radiographs, study models, pulp vitality tests, and photographs. Radiographs should be individually listed (eg, periapical #9, right molar bitewing). Diagnostic testing cannot be performed without an examination, which also must be recorded in detail. When dentists perform an oral exam, he or she is doing more than just glancing at the teeth; soft tissues are palpitated, periodontal health is established through probing, oral cancer screenings charted, as well as any deviances in mobility, appearance, and texture. Any negative findings must also be recorded.

• Treatment rendered should be broken down as much as possible when documenting. When restoring a tooth, merely writing “#31 MO” is not enough. Details need to be included on the type and quantity of anesthetic, the type of restorative material used, all materials used in the process of placing the restorative material and shade, if applicable. Document how the patient tolerated the procedure and describe any other events that were relevant to the procedure.

• Copies of the instructions given to the dental laboratory concerning the fabrication of patient appliances or cast restorations should be kept along with the patient record. There may be an occasion when the dentist may need to refer back to the information in cases of suspected allergies or defective product.

• Never talk to patients over the phone without first pulling their charts so the conversation can be immediately documented and, should you need to refer to something in the record, the information is readily available. Quotation marks (“ ”) should be used whenever possible when recording an actual conversation and record the identity of the person being quoted. Always give patients the opportunity to talk to or see the doctor; never dismiss their concerns as something petty. To maintain confidentiality, always hold telephone conversations out of earshot of other patients. At the end of treatment, document when patients are satisfied or happy with a certain outcome. Equally, document if the patient is dissatisfied with the treatment rendered or service received and note any steps taken to alleviate patient concerns or discomfort.

• When a patient is referred to another practitioner, simply writing down that a patient was “referred out” is inadequate. Reference the consulting specialist by name, cite the rationale for the referral and how soon the patient should make an appointment with the specialist. Usually, when a general dentist refers a patient to a specialist, the referring dentist is not held accountable for any negligence on the part of the specialist provided the referrer has no control over and provides no direction on the mode of treatment used by the specialist. Follow up with the specialist and include the consulting dentist’s reports in the patient chart.

• When medications are prescribed, always document the full name of the drug prescribed, the dosage amount, strength, duration, administration and refills, if any. If a prescription is called in, make sure to pull the patient’s chart and record the call. Discuss, inform, and record possible side effects to show that the patient was made aware of any ill effects.

• Outline any instructions given to the patient for services that require home care. Never misjudge the ability of your patient to comprehend instructions, no matter how simple they may seem to you or your team. Instructions should be given verbally and in writing then documented in their chart. If you provide a pamphlet or additional information to your patient, note it in the record. Even simple directions on brushing and flossing should be cited, as should any instructions for follow-up by phone or recare visit.

• Document when and why the patient is returning back to the practice. If the patient fails to return as instructed, note it in the record. In the event of a claim against the dentist, evidence of noncompliance from the patient may be labeled as “contributory negligence” by a court. This verifies that the patient has contributed to the supposed injuries and must likely accept some of the blame for an unsatisfactory treatment outcome, shifting the entire blame away from the dentist and the dental practice.

Patients’ Right to Privacy

Under HIPAA, all patients, medical or dental, have a right to privacy. The outside cover of the clinical record should only exhibit the patient’s name and/or the account number. Because records are private, any notations of medical conditions, allergies, and other health-history information should not be recorded on the outside folder. Likewise, no financial notations should be on the outside folder. All notations belong inside the chart for authorized personnel use only. If the chart must be identified, an abstract system should be used that only the dental team understands.

Transferring Patient Records

The dentist owns the physical record of the patient and is the legal custodian of the document. If a dentist is an employee of a group practice, ownership usually lies with the practice.

Patients do not have the legal right to possess their original record, but they do have the right to view, evaluate, scrutinize, request, and obtain a copy of their personal dental records. It is important to become familiar with the laws of your particular state governing this issue. Information for each state can be found through the state board of dentistry/dental examiners. Typically, patients must be able to gain access to their records within a reasonable time frame. Practices may charge a small fee for copying records, which is often defined within the state’s privacy laws. A practice may not refuse to release a patient’s record because of an outstanding account, especially if another practitioner is requesting the record or the patient is transferring to another for care.

Radiographs are a vital part of a patient’s clinical record, and laymen cannot interpret them. When radiographs are taken, the patient is paying for the interpretation of the radiograph(s) and not the actual film itself. Therefore, in most states dentists typically maintain ownership of patient radiographs. However, patients have the right to obtain copies of their radiographs. Under no circumstances should original records, including radiographs, be released to anyone. Copies should always be forwarded. The one exception to this rule is Subpoena Ducus Tecum, which commands that the dentist present his or herself at court with the original records. Under these circumstances, copies of the original records should be made and retained in the dental practice.

Due to the confidential nature of the dental record, always make sure that you have a valid, signed Release of Information form from the patient before sending out any copies to the patient, the patient’s representative or another provider. Verify the signature on the form with the one you have on file. Never send anything out of the office without the dentist’s knowledge and approval. Document on the original record the date, as well as where and to whom the copies were sent.

Financial Records Organization

A practice’s financial records must be kept for a minimum of 7 years, but most practices keep them indefinitely. No financial information should be kept in the patient chart. Ledger cards, insurance benefit breakdowns, insurance claims, and payments vouchers are not part of the patient’s clinical record and should not be included in or on the front cover of the record. If such information must be filed, keep it under separate cover in a different location of the practice.

There are several methods of organizing active insurance explanation of benefits (EOBs). One method is to have a separate folder for each business day of the year where all EOBs processed on that particular day would be found in that folder. Another more common method of organization is to have a folder for each letter of the alphabet, organizing the EOBs alphabetically with the most recent visit on top for patients who have more than one EOB in a given year. At the end of the year, some practices will retain the previous year’s EOBs for the first quarter in a convenient location until all claims have been received from the previous year. Then the records are stored as inactive. Most practices maintain 3 year’s worth of inactive EOBs onsite. Each year, destroy the oldest file of retained EOBs by shredding or consider hiring a professional company to come and collect sensitive documents and shred them onsite.

Retention of Clinical Records

Regardless of particular state laws regarding record retention, it is recommended that all clinical records, including radiographs, be kept for an indefinite period of time. If space is a concern, consider alternative methods of storage. Old, inactive records can be committed to microfilm or microfiche. Some companies specialize in record retention; they can help you with storage or create microfilms and microfiches from paper records. If a practice opts to dispose of old, inactive charts, these companies also can furnish a “Certificate of Destruction.” Common practice for many dental practices today is to destroy inactive patient records.

Record Protection

Computers are now a fundamental part of most dental practices. Electronic communications for patient-care purposes must meet the standards of HIPAA. Confidentiality remains a prime concern and certain measures must be taken to ensure that patient information is neither shared nor accessible to unofficial parties. Also, the authenticity of the original record must be maintained with electronic transmissions. It is important to make sure dental software packages contain features that address both confidentiality and the integrity of the original records. When choosing a computerized charting program, the inability to change records must be considered. Once an entry is made, the only way to modify that entry should be to amend it in the form of an addition; once entered, an existing entry should not be able to be altered. At the end of each business day, dental practices with computerized systems run a back up of all data and patient information. This is sometimes done in the middle of the night automatically, or manually at the end of the day or first thing the following morning. A copy of the back-up is brought offsite in case of an event that would wipe out practice electronic information, such as a fire.

Standard of Care

Standard of care is generally misinterpreted within the dental profession. Many believe that it is a state law or set of regulations listing specific steps a dentist must follow. It is not a state law or regulation, but a legal concept that provides common limits that a dentist must comply with in a given situation. The standard of care that a dentist must meet is the basic practices of highly regarded dentists who have comparable education and knowledge, who practice in similar disciplines and those who practice in a comparable area. When a dentist fails to meet the standard of care and the patient is wronged due to negligence, the dentist may be held liable for malpractice.

Most medical and dental malpractice claims arise from an unfavorable interaction with the doctor and not necessarily from a poor treatment outcome. The statute of limitations for filing a lawsuit varies from state to state. Generally, plaintiffs must file within 5 years of the last date of service or within 3 years of the date of discovery. As a point of reference, it takes approximately 7 years to settle a claim.

If a dental team member is notified that he or she is involved in a complaint, immediately inform the doctor. Do not call or to contact the patient and do not add anything to the patient’s record, no matter how important or helpful you think it might be; an addendum on a separate sheet of paper can be created with the additional information. It cannot be stressed enough—never send out copies of a record to anyone without first notifying the dentist and verifying there is a signed Release of Information form in the record. The dentist must be aware of all duplicates of records that are transferred or sent out, no matter the reason. It is very important not to document in the clinical record conversations with attorneys and/or the malpractice insurer. Additionally, do not file in the clinical record any lawsuit correspondence or letters from attorneys and/or the malpractice insurance company. Keep this documentation under separate cover in a secure location.

Legal Responsibilities

The legal responsibilities of a dentist to a patient include many areas of patient treatment (Figure 23). The dentist may refuse to treat a patient; however, this decision must not be based on the patient’s ethnicity, color, or faith. Additionally, the Americans with Disabilities Act protects individuals with infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). A patient infected with HIV cannot be refused treatment simply because of the disease. The only exception would be if the HIV patient had a unique condition, such as an endodontic infection of a salvageable tooth that required the care of a specialist, where the dentist would refer any patient with the same condition to a specialist, regardless of their medical status. Individuals cannot be refused treatment on the sole basis of their medical condition.

Patient abandonment refers to the discontinuation of care after treatment has begun, but before the treatment has been completed. The dentist may be liable for abandonment if the dentist terminated the dentist–patient relationship without giving the patient reasonable notice, usually 30 days. Even if the patient refuses to follow treatment instructions or fails to keep appointments, the dentist is obligated to give the patient another appointment. After notification of termination of the dentist–patient relationship, the dentist is obligated to continue care during those 30 days so the patient has time to find another provider. The dentist can be accused of abandonment if he/she chooses to go out of town without making arrangements for another dentist to be available for emergencies, or without leaving a forwarding telephone number for the patient to call for care. Patients also have responsibilities to their dentist. The patient is legally required to pay a reasonable and agreed upon fee for services rendered. The patient is also expected to cooperate and follow instructions regarding treatment and home care.

Due care is a legal term referring to the appropriate and satisfactory care or the absence of negligence. The dentist has a legal commitment to use due care in treating all patients and this commitment applies to all treatment procedures. For example, when prescribing an antibiotic for an oral infection, due care implies that the dentist is familiar with the medication, its properties and side effects. The dentist must also have adequate information about the patient’s health to know whether the drug is suitable for the patient.

Prevention of Lawsuits

While patients may bring a lawsuit against the dentist, it does not guarantee that they will win. The following four circumstances, often referred to as the “Four Ds,” all must be present for the malpractice suit to be victorious:

• Duty: a dentist–patient relationship must exist to establish the duty

• Derelict: negligence occurred as a result of not meeting the standard of care

• Direct cause: the negligent act was the direct cause of injury

• Damages: the pain and suffering of the patient, loss of income, medical bills incurred are all included in damages

Malpractice is professional negligence. In dentistry there are two types of malpractice: acts of omission and acts of commission. An act of omission is the failure to perform an act that a “reasonable and prudent professional” would perform. An example would include the dentist who failed to diagnose a carious lesion because radiographs were never taken. An act of commission is performance of an act that a “reasonable and prudent professional” would not perform. An example would include the dentist prescribing an antibiotic that the patient is allergic to, without glancing at the medical history or conferring with the patient about allergies to medications. In most malpractice cases an expert witness is not needed. Under the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur, “the action speaks for itself,” the evidence is quite clear. An example is performing a root canal on the wrong tooth.

The major areas of risk management involve three simple concepts:

• Maintaining accurate and complete records

• Gaining informed consent prior to an examination or treatment procedure

• Doing everything possible to maintain the highest standards of clinical excellence

Perhaps the greatest factor in preventing legal issues is maintaining an atmosphere of excellent rapport and open communication with all patients. When patients become frustrated and feel they are not being heard, lawsuits are more likely to occur in order to get the attention of the dentist.

Informed Consent

One of the best ways a dental practice can prevent lawsuits is by obtaining informed consent from patients. The concept of informed consent is based on the idea that it is the patient who must pay the bill and endure the pain and suffering that may result from treatment. Informed consent from the patient is based on the information provided by the dentist about the dental treatment in question. Two things must occur for the patient to give informed consent: the patient must be fully informed of the treatment and be allowed to ask questions, and the patient must be of legal age and sound mind to give consent. The dentist must give the patient enough information about the oral condition and all available treatment options. If there are any contraindications or possible undesirable outcomes they are typically presented with each treatment option. The patient and the dentist then openly discuss these options and the patient chooses the most suitable treatment choice.

Informed consent is further broken down into implied and written consent. Implied consent can be described as the case where a dental patient enters the office for an appointment as a new patient, implying consent for at least a dental examination. Likewise, when a dentist recommends a new restoration to replace a deteriorating restoration, the patient is implying consent if he or she does not object to the proposed treatment. Implied consent is a less reliable form of consent in a malpractice suit. The preferred means of gaining consent is through written consent, which is to physically obtain and document the patient’s consent so a paper record exists.

The patient, at any time, has the right to refuse treatment. If a patient refuses proposed treatment options, it is the duty of the dentist to inform the patient about the likely negative outcomes and obtain the patient’s informed refusal. By obtaining the patient’s informed refusal, the dentist is still responsible for providing the standard of care. A patient cannot consent to poor quality care and the dentist cannot legally or ethically agree to perform such care. For example, if a patient refuses periodic examinations and radiographs, the dentist may refer the patient to another provider for treatment because the dentist considers that both periodic examinations and radiographs are an essential standard of care. Another practitioner, however, may be willing to treat the patient without radiographs or periodic examinations and may request a written statement signed and dated by the patient documenting this agreement. The statement is then filed with the patient record.

There are some exceptions to disclosure of information when referring to informed consent. The dentist is not under any legal obligation to disclose information about the proposed treatment in the following circumstances:

• The patient requests not to be advised.

• The proposed procedure is straightforward and life-threatening risk is unlikely (eg, death from a sealant).

• The treatment is minor and rarely results in serious side effects (eg, the taking of an impression with alginate material).

• The information would be so upsetting that the patient would be unable to make a rational decision; known as therapeutic exception.

Patients who are minors must have parental, custodial parent, or legal guardian consent before any dental treatment is rendered. The dental practice must have on record the name of the custodial parent in the case that the child lives with one parent. In situations of joint custody of child patients, letters of consent, authorization, and billing information on record from both parents are key in the instances where emergency treatment is needed and only one parent is in the practice with the child.

Documenting Informed Consent

In many states there is no specific protocol for the documentation of informed consent. At the very least, the patient’s record should show that the patient received information about the benefits, risks, and alternatives of the proposed treatment and whether the patient consented or refused the options. Any time treatment is extensive, invasive, or has an uncertain outcome, a written consent from the patient is recommended. The patient, dentist, and a witness sign the document, the patient receives a copy, and the original is filed in the patient record (Figure 24).

Informed consent is a process involving in-person discussion between the treating dentist and the patient. Adequate time should be allowed to answer all of the patient’s concerns and questions. If the patient is uncertain, treatment should be delayed and the patient should be allowed to go home and think it over. The dentist should then follow up with a courtesy telephone call inquiring if the patient has any additional questions.

Consent forms should contain the following information:

• The nature of the proposed treatment

• Benefits and alternatives

• Risks and potential consequences of not performing treatment

• Other information specific to a particular situation

Whenever a patient’s case may be outside the scope of practice for a dentist, the patient should be referred to another practice. The dentist must inform the patient that the needed treatment cannot be properly performed in the practice and requires the services of a specialist. The dentist should assist the patient in finding a suitable specialist. Many malpractice claims involve the failure of a dentist to refer a patient to a specialist. This is frequently seen in general dentistry. It is important that the dentist establishes the patient’s periodontal baseline, as well as existing conditions of the teeth and restorations. When referring a patient to a specialist, the following information must be documented in the patient record:

• Description of the problem

• Reasons for referral

• Name and specialty of the referral dentist

• Whether patient has consented to the referral or not

Another area of risk management is the documentation of broken appointments or last-minute cancellations. These actions can be interpreted as contributory negligence on the part of the patient. Contributory negligence occurs when the patient’s actions, or lack of action, negatively affect the treatment outcome. With proper documentation, the practice is protected against legal recourse should the patient decide to claim negligence against the dentist. An example would include the patient who was told a deep area of decay was found on a radiograph that was close to the nerve of the tooth and needed immediate treatment before the condition worsened. The patient broke several appointments (contributory negligence) and 12 months later requires extraction of the tooth as a result of the continued, extensive decay.

The primary goal of keeping good dental records is to maintain continuity of care. Diligent and complete documentation and charting procedures are essential. Also, because dental records are considered legal documents, they help protect the interest of the doctor and/or the patient by establishing the details of the services rendered. In malpractices cases, an expert witness usually helps the court decide if a dentist did or did not perform in accordance with the accepted norms, guidelines and degrees of competence that can be reasonably expected from such a professional. Dental associations and state dental boards propagate standards and recommendations that typically determine the standard of care.

The outcomes of dentistry can be unpredictable. With proper documentation, the dental practice will be armed to fight any legal issues directed its way.

Conclusion

The practice administrator must act as a professional liaison between the dental team members and the patients they serve. The person employed in the position of practice administrator must be capable to effectively utilize the many forms concerning dental documentation and HIPAA protection laws. The responsibilities of records management and legal documentation are best handled by a knowledgeable practice administrator. To be able to handle those duties with educated efficiency, the practice administrator must understand the language and procedures of dentistry and be able to effectively communicate them to the patient for proper consent to serve all parties best interests.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Natalie Kaweckyj, LDARF, CDA, CDPMA, COMSA, COA, MADAA, BA has worked in the dental assisting profession as an administrator, a clinician, and an educator. She is currently a Licensed Dental Assistant in Restorative Functions, Certified Dental Assistant, Certified Dental Practice Management Administrator, Certified Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery Assistant, Certified Orthodontic Assistant, a Master of the American Dental Assistants Association, and holds several expanded function certificates. Natalie graduated from an ADA accredited dental assisting program at Concorde Career Institute and graduated with a BA in Biology and Psychology from Metropolitan State University. She is currently pursuing her Master’s in Public Health with a focus on epidemiology through Independence University.

Natalie is currently serving as ADAA President-Elect. She has served in many capacities at the local and state levels of her state association, and is a past ADAA Secretary, Seventh District Trustee, and Director to the ADAA Foundation. In addition to her association duties, Natalie is very involved legislatively with her state board of dentistry and state legislature in the expansion of the dental assisting profession. She volunteers at two community dental clinics, serves on the MN RDA Exam Committee in Expanded Functions and is an advisory board member to the Century College Hygiene Department. Natalie is also affiliated with OSAP, the National Association of Dental Assistants, and the American Association of Dental Office Managers. She has authored several other courses on a wide variety of topics for the ADAA and is a speaker on dental topics locally and nationally.

Acknowledgement of Contributing Authors

Wendy Frye, CDA, RDA, FADAA, currently lives in Fenton, Missouri, where she is a chairside dental assistant and implant treatment coordinator in a periodontal office. She is a Certified Dental Assistant, Registered Dental Assistant and Fellow of the American Dental Assistants Association. Wendy graduated from the ADA accredited dental assisting program at Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Wendy has served in many various capacities on the local and state levels of the Iowa and California Dental Assisting Associations.

Lynda Hilling, CDA, MADAA, lives in Billings, Montana. She is a Certified Dental Assistant and has been employed in the private practice of Michael W. Stuart, DDS, for the last 10 years as a chairside assistant. Lynda began her dental assisting career as an on-the-job trained assistant and then challenged the CDA exam in 1999. Lynda is a Master in the American Dental Assistants Association. Lynda has served on the Executive Board of the Montana Dental Assistants Association, including the Presidency.

Lisa Lovering, CDA, CDPMA, MADAA, is a Certified Dental Assistant and a Certified Dental Practice Administrator and is employed chairside in the private practice of Michael W. Stuart, DDS. Lisa began her dental assisting career as an on-the-job trained assistant and then challenged the CDA and CDPMA exams.

As a member of the American Dental Assistants Association, Lisa has received her Mastership. Lisa has served on the Montana Dental Assistants Dental Assistants Association Executive Board, including the Presidency. She is currently the Tenth District Trustee.

Linette Schmitt, CDA, LDA, MADAA, is a graduate from the ADA accredited dental assisting program at Hibbing Community College. Linette currently works as a chairside assistant in a large group practice. She is a Minnesota Registered Dental Assistant and a Certified Dental Assistant, and is also certified to administer nitrous oxide analgesia. She is a member of the American Dental Assistants Association and holds an ADAA Mastership.

She has served in many capacities at the local and state levels of her association, and is currently serving as ADAA Seventh District Trustee. Linette is legislatively involved with the Minnesota Board of Dentistry’s Policy Committee.

Wilhemina R. Leeuw, MS, CDA, is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Dental Education at Indiana University Purdue University, Fort Wayne. A DANB Certified Dental Assistant since 1985, she worked in private practice over 12 years before beginning her teaching career in the Dental Assisting Program at IPFW. She is very active in her local and Indiana state dental assisting organizations. Professor Leeuw’s educational background includes dental assisting both in clinical and office management capacities, and she received her Master’s degree in Organizational Leadership and Supervision. She is also the Continuing Education Coordinator for the American Dental Assistants Association.

References

1. Andujo E. Dental Assistant: Program Review and Exam Preparation (PREP). Stamford, CT: Appleton and Lange, 1997.

2. Bird D, Robinson D. Modern Dental Assisting. 8th ed, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2005.

3. Finkbeiner BL, Johnson CS. Mosby’s Comprehensive Dental Assisting: A Clinical Approach. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1995.

4. Finkbeiner BL, Finkbeiner CA. Practice Management for the Dental Team, 6th ed, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Inc, 2006.

5. Finkbeiner BL. Basic Concepts of Dental Practice Management. American Dental Assistants Association. 2006.

6. Gaylord LJ. The Administrative Dental Assistant. 2nd ed, St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2007.

7. Metivier AP, Bland KD. General Chairside Assisting: A Review for a National General Chairside Exam. American Dental Assistants Association. 2006.

8. Phinney Donna J, Haldstead JH. Delmar’s Dental Assisting: A Comprehensive Approach. 2nd ed; Clifton Park, NY: Delmar, 2004.

9. Requa-Clark B, Holroyd SV. Applied Pharmacology for the Dental Hygienist. 3rd ed, St. Louis: MO: Mosby, 1995.