You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Glossary:

Etiquette—Correct social behaviors and good manners according to members of a community

Communication—The exchange of thoughts or messages that are understood between a sender and receiver

Loudness—Referring to the volume of a speaking voice

Pitch—Referring to the tone quality of someone’s voice

Rate—Referring to how fast someone is speaking

BUSINESS OFFICE ETIQUETTE

Professional business etiquette refers to the social guidelines and manners to be followed in business situations when dealing with patients, staff, and other clients. The professional behavior may be based on custom and morality. In reality, business etiquette in the dental office is applying acceptable social guidelines, demonstrating social manners, and communicating effectively with all the persons who come into the dental office on a daily basis.

Because this course is about verbal and non-verbal communication, the emphasis will be placed on these specific topics. However, Figure 1 includes tips for professional etiquette in the dental office that can aid in all communication.

VERBAL COMMUNICATION

The Speaking Voice

Face-to-face communication is generally more effective than telecommunication because it provides the following advantages:

Participants are able to:

• talk informally before and after an appointment or meeting.

• observe others’ body language and facial expressions.

• discuss difficult issues more effectively.

• have an interactive conversation with several people.

Whether speaking person-to-person or on the telephone, the speaker’s voice is important in all forms of verbal communication. Typically, by the time a person completes their professional education, voice qualities have matured and changes have generally been made to eliminate annoying habits. However, a person can often glide into old habits and it is beneficial to examine the speaker’s voice to ensure that the best voice is being put forward during daily communication.

The components of the speaking voice include loudness, pitch, quality, and rate.

Loudness is the volume of the voice. It should be of moderate volume so that the conversation can be properly heard but that others are not distracted. If a person asks for a repeated message, the speaker may need to increase their volume. If those around that speaker mention that they can always hear the conversations in other areas of the office, the speaker should make an effort to lower the volume. This takes some practice but a little effort can make a world of difference.

Pitch is the tone of the voice. This is not as readily modified as the voice volume. A low, gravelly voice or a high-pitched, squeaky voice can both be very annoying to the listener. To modify either of these situations may require some exercises that must be followed routinely. The library, telephone company, and online video resources offer references for modifying voice pitch. If necessary, it may require working with a voice therapist or coach, but it is worth the effort to improve verbal communication.

Voice quality refers to the physical and psychological factors of the voice. Factors such as depression, excitement, anger, or a cold can all impact the quality of the voice. Care should be taken to avoid sarcasm or caustic tones in the voice. To aid in improving the quality of the voice one should be alert, expressive, interested, natural, and speak distinctly. To speak distinctly, avoid chewing gum, biting on a pencil, or covering the mouth with the hand.

Rate is a quality that we have all observed when speaking with other people. Some people speak so rapidly that it is difficult to understand the message. On the other hand, someone who speaks very slowly can cause the listener to become impatient. The speaker can take time to consult with others and ask if voice rate is adequate to promote good understanding. If not, again, the speaker can practice increasing or decreasing their voice rate to ensure proper understanding.

Verbal Image

To present a good voice image the speaker should be alert, expressive, interested, natural, and speak distinctly. Patients and clients can easily detect a phony image and it will only lead to a lack of patient confidence in the end. Avoid slang as it is not in good taste nor does it present a good professional image.

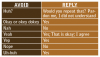

Often the way a phrase or sentence is stated will prompt a negative response from the patient. For instance, a dental assistant may say to a patient in the reception room, “Mrs. Vazquez, would you like to come in now?” The obvious response is “No,” from Mrs. Vazquez. However, if rephrased to say, “Mrs. Vazquez, come in please,” or, “Mrs. Vazquez, the doctor will see you now,” any possible dissention from the patient is avoided.

The speaker should think about phrasing and determine if what is said is positive and provides a sense of comfort to the patient. It is wise to have a list of these words or phrases for new employees with substitute words or phrases for each (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

The Use of Proper Grammar

It is impossible in a course of this length to provide an entire grammar course. However, it is necessary to draw attention to some of the most common errors in grammar. It is important that the entire staff is aware of the need to use proper grammar and, when necessary, should be willing to make the proper changes in grammar to ensure a good professional image. There are a couple of good grammar reference books on the market that can be purchased on the Internet. These would be good additions to the dental office library and the administrative assistant may want to assign readings to staff members who are using poor grammar in the office. The Only Grammar Book You’ll Ever Need by Susan Thurman, Adams Media, Avon, MA, and The Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation by Jane Strauss, 10th ed., Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, are both excellent references.

Following are a few explanations with examples of common misuses of nouns, verbs, prepositions, adverbs, and adjectives. This is provided in a form that requires a decision—which sentence is correct—and then the rationale is provided for the proper choice as indicated.

Subjects and Verbs

Be certain the subject and verb are in agreement. A singular subject takes a singular verb and a plural subject takes a plural verb. A hint is to recognize which verb to use with he or she and which verb would be used with they. See the following examples in the right-hand margin for subject and verb agreement (Example 1 through Example 5).

Can or May

Both of these words are verbs. Can and could are used to indicate the ability to do something. May or might are verbs that are basically alike, in the senses of possibility and permission (Example 6).

Pronouns

A pronoun is a word that is used in the place of a noun. Pronouns may be in one of three cases: Subject, Object, or Possessive. Common subject pronouns are: I, you, she, he, we, and they. Common object pronouns are: you, me, him, her, it, us, or them. Common possessive pronouns are: yours, mine, his, hers, ours, theirs, and its. Possessive pronouns show ownership and do not need an apostrophe.

Adjectives and Adverbs

Though there appears not to be as many errors when using adjectives, there are often errors in the verbal use of adverbs. Here are some examples.

An adjective is a word that modifies a noun or pronoun. The pronoun may come before or after the word it describes. For instance: She is an efficient hygienist. The hygienist is efficient. Try to identify the adjective in each of the following sentences.

a. The new doctor prefers to use computer imaging.

b. The smaller boy is the first patient.

c. The grey cabinet is used for storage.

d. The clinical record is complete.

Below the italicized word is an adjective. The word modifies the noun. In reality, it adds a description to the noun to more clearly define it.

a. The new doctor prefers to use computer imaging.

b. The smaller boy is the first patient.

c. The grey cabinet is used for storage.

d. The clinical record is complete.

If the speaker refers back to basic English classes, they will recall that the adverb answers, how, when, where, and why. An adverb can modify adjectives, verbs, and other adverbs but not a noun. Generally when a word answers the question of how, it is an adverb. For instance:

a. The doctor works rapidly.

This statement answers how the doctor works. So rapidly modifies the verb works.

b. The doctor works very rapidly.

This statement answers the question of how rapidly. Thus, very modifies the adverb rapidly.

If the adverb can have a “ly” added to it, place the “ly” on the end of the word.

The new assistant thinks slowly. Slowly tells how the assistant thinks. “She is a slow thinker” does not answer how. Thus, slow is an adjective.

There are some words to which a “ly” cannot be added. For instance, “She drives fast.” No one can drive fastly. However, fast does answer how and is an adverb.

Here are just a few more hints that deal with the use of certain words that can often be confusing in grammar.

Well versus Good

Good is an adjective, whereas well is an adverb.

He did a good job filing. Good describes the job.

He did the job well. Well answers how.

Use well when describing health.

Correct: He does not feel well today.

Incorrect: He does not feel good today.

Complications Using a Preposition

A general rule is to never end the sentence with a preposition. However, it is sometimes difficult so just do not use extra prepositions when the meaning is clear without them.

Correct: That is something I cannot agree with.

Correct: That is something with which I cannot agree.

Incorrect: Where did the doctor go to?

Correct: Where did the doctor go?

Correct: I should have placed the instruments in the drawer.

Incorrect: I should of placed the instruments in the drawer.

As stated earlier it is not feasible to cover all parts of grammar but this has been a short review of the basic concepts and has provided examples of some common errors.

LISTENING SKILLS

A valuable step in effective communication is listening. A person can hear the words and yet not be able to understand them. Listening requires that both the speaker and receiver actively listen for the meaning as well as the individual words. The following suggestions may help in improving a person’s active listening skills. Take time to review these suggestions and put them into practice.

• Be prepared to listen. Avoid distractions from outside thoughts and direct full attention to the speaker.

• Also listen with the eyes. Observe the person’s body language such as facial expressions, gestures, and posture.

• Listen for facts. Listen for key words and mentally repeat the ideas and points.

• Listen for feelings. Attempt to determine if what is being said is really what is meant or if there is hidden meaning below the surface.

• Avoid allowing the mind to wander. A person can generally absorb more words per minute than are spoken. Actively listening to the conversation is important to keep the mind focused.

• Avoid biases and prejudices that may surface and lead to false assumptions.

• Use reflective listening. Listen to what has been said, reflect on it, and then restate or paraphrase to ensure understanding and acceptance.

Good listening skills require that the listener understands a person before speaking. Such action will ensure improved relations with the patients, staff, and other persons and may even result in fewer conflicts and better understanding.

NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION

Appearance is part of non-verbal communication. The first image a person forms is from the appearance that the speaker presents. Like it or not, when a person dresses differently than is our style or differently than what is expected of a professional, a person tends to assume that the personalities are very different. This is not true. It is very difficult to set aside these images and look beyond the person’s personal appearance. However, in the dental office it is important that the image be acceptable to the general public. Visible piercings and tattoos are looked on unfavorably in the dental profession. In addition, brightly colored nails and extreme make-up do not create a professional image.

When working with the patients, dental staff, community, business people, and colleagues, the following characteristics should be displayed to create a successful image:

• Good self-esteem

• Self-confidence

• Good vocabulary

• Caring attitude

• Appropriate facial expressions

• Good eye contact

Often the eyes and facial expressions tell a different story than the words that are spoken. Time must be taken to observe the facial expressions of the receiver of the information to be certain that the message being heard is really the message being transmitted by the speaker. Both the speaker and receiver need to be cautious with facial and eye expressions so that they are not misinterpreted during the conversation.

There are many gestures used in non-verbal communication. The following are typical gestures often recognized in the dental practice.

Grasping the Arms of the Dental Chair

This gesture indicates nervousness or fear. The patient who locks their ankles together or clenches their hands may be expressing fear by holding back emotions. Attempt to relax the patient by talking to them about something of interest and ask if anything can be done to help them relax.

Crossed Arms and Legs

A patient or staff member may use the gesture of crossed arms or clenched fists to indicate disagreement or defensiveness. It may occur when the person is being ignored. Therefore, attempt to involve the person in conversation or ask them if they may need help. Often simply talking to the person will cause them to relax the defensive attitude and they will relax. Another gesture that indicates this same type of attitude is indicated when a person turns their back away from the speaker.

Hand Over Mouth

This is a gesture that is more common in a dental office than it is in routine activities. This gesture often indicates a person’s embarrassment about their teeth, either to cover up missing or decayed teeth.

Rolling Eyes

This is a gesture that often indicates doubt or disbelief of another person’s action. Letting the eyes roam and seldom making eye contact can signal that the person is not paying attention when listening to the speaker.

Touching

Touch is a powerful gesture. The soft placement of someone’s hand or a kind pat on the back or shoulder can relay a comforting message. However, in the dental profession, touch can be comforting or it can lead to a sexual harassment suit. Therefore, one must be extremely careful when using this effective communication tool. Any nonconsensual touching can be considered battery. Thus, the dental professional must be cautious and if the patient is displaying discomfort or fear, ask if they want their hand held. In fact, they may even be anxious to grab a hand for security. Typically, a gentle touch and smile can do wonders in promoting care and concern.

Posture

A person’s posture can often indicate depression, excitement, or even anger. Though this is not often resolved in a dental office, one should be aware of the patient’s posture as it may indicate some form of medical condition.

Positioning of the dental staff can impact the patient. When consulting with a patient, it is more comforting for the dental professional to sit in front of the patient and lean forward to present a feeling of caring and interest. Sitting behind a desk indicates an air of authority. Standing or sitting across the room may also convey a negative message of reluctance to talk. The dental professional should practice good postural techniques to create a positive image and this will also promote good personal health.

Pointing

Pointing is often an accusatory gesture and causes discomfort. People should avoid such gestures unless pointing to a visual aid during a discussion with the patient or staff person.

PERSONAL SPACE

Personal space is important to an individual. It is often obvious when someone’s personal space has been invaded, as the person will tend to back up a step or two (Figure 4).

Personal space is evident in the reception room, too. Look at the seating arrangement when a person enters the reception room. If there is a seat available so that the person can leave an empty chair between him and a stranger, the new person is likely to leave the chair vacant. Personal space ranges from 1.5 to 4 feet and intimate contact includes space from physical touching to 1.5 feet. The more familiar and comfortable a person is, the closer the space they will allow.

SUMMARY

Communication is a key component to the success of a dental practice. Whether the message is a verbal or non-verbal, the information delivered must be professional in manner. Communication requires active listening from both parties to ensure understanding. Proper use of basic grammar and non-verbal cues will enhance communication throughout the dental practice.

REFERENCES

Finkbeiner B, Finkbeiner C. Practice Management for the Dental Team. 7th ed. 2011; Mosby Inc.

Oliverio, Pasewark, White, The Office – Procedures and Technology. 5th ed. 2006; Thomson.

Strauss J. The Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation. Jossey-Bass, 10th ed., San Francisco, CA.

Thurman S. The Only Grammar Book You’ll Ever Need. 2003; Adams Media, Avon, MA.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Betty Ladley Finkbeiner, CDA-Emeritus, BS, MS, is a Faculty Emeritus at Washtenaw Community College in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where she served as chairperson of the dental assisting program for over three decades. Betty began her career as an on-the-job trained dental assistant for the late Joseph S. Ellis, DDS, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and later became a CDA and an RDA in the state of Michigan. She received bachelors and masters degrees from the School of Education at the University of Michigan. She has served as a consultant and staff representative for the American Dental Association’s (ADA) Commission on Dental Accreditation and as a consultant to the Dental Assisting National Board. She was appointed to the Michigan Board of Dentistry from 1999–2004.

Ms. Finkbeiner has authored articles in professional journals, authored several continuing education classes, and co-authored several textbooks including: Practice Management for the Dental Team; Comprehensive Dental Assisting: A Clinical Approach; Review of Comprehensive Dental Assisting; and a handbook entitled, Four-handed Dentistry: A Handbook of Clinical Application and Ergonomic Concepts. She has co-authored videotape productions including Medical Emergencies for the Dental Team; Four-handed Dentistry, An Ergonomic Concept; and Infection Control for the Dental Team, and lectured to University of Michigan dental school classes and many dental meetings. Currently retired, she continues to write, lecture, and provide consultant services in ergonomic concepts to practicing dentists throughout the country.