You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Ideally, implant therapy in the maxillary anterior region ends with natural-looking restorations that are harmonious with the surrounding dentition. However, when an implant fixture is positioned or angulated too far facially, the esthetics and long-term success of the restoration can be compromised.

Prosthetically Driven Implant Planning

In implant dentistry, beginning with the end in mind means "crown-down" planning, starting with the teeth in space and designing the surgery accordingly. The crown contours, however, can be deceiving in this process. The facial crown contours of a maxillary anterior tooth generally follow two planes: one that is parallel to the facial root surface and another that is inclined approximately 12° to 15° palatal to the incisal plane.1 Following the first plane will over-angulate the implant facially, and following the second plane will likely position the body of the implant too far facially. These malpositions can result in implant-restoration axis problems and obstruct facial hard and soft tissues, which can make the implant challenging to restore and potentially contribute to failure. The ideal implant-restoration relationship exists when the implant fixture is angulated along the long axis of the tooth in the sagittal plane and positioned palatally to the incisal edge of the adjacent teeth in the transverse (ie, occlusal) plane (Figure 1).

Osseous Anatomy and Volume

The anatomy of the available bone at an anterior implant site will inform the positioning of the implant as well as the selection of the restoration. An analysis of the sagittal bone volume permits assessment of an individual's bone phenotype and the potential need for grafting.2 In the "triangle of bone" concept, bone volume is analyzed by visualizing a triangle connecting the points at the widest part of the facial bone and the widest part of the palatal bone with a final point that bisects the alveolar crest.3 Evaluating bone volume within this triangle can help to determine the ideal implant position, any grafting requirements, the necessity of placing an angled abutment or cement-retained restoration, and the thickness of the bone that will ultimately be facial to the implant.

After tooth loss, a decrease in the width and height of the alveolar ridge is expected.4 Even after guided bone regeneration, the implant will still need to be placed in a position that is more palatal when compared with the original root position. The immediate placement of implants introduces additional dangers regarding facial positioning. Kan and colleagues proposed a classification system for sagittal root position, with the most prevalent root position being against the labial cortical plate.5 Although this position is ideal for engaging palatal bone, it requires osteotomy penetration through the palatal wall at an oblique angle, and without caution, the osteotomy drill or implant may slide on the palatal wall and migrate facially if a non-guided surgical approach is used.

The thickness of the facial bone is of paramount concern due to the scarcity of blood supply in this region. The majority of the sites in the anterior maxilla present with less than 1 mm of buccal wall thickness, which implies minimal, if any, cancellous blood supply.6 The dimensional changes of bundle bone that accompany extraction are related to eliminating another source of bony blood supply-the periodontal ligament.7 Appropriate implant placement that allows for what Buser and colleagues described as a 1.5-mm to 2.0-mm facial bone thickness "safety zone" permits perfusion and thus dimensional stability of the bone.8 When an implant is facially malpositioned, the thickness of the facial bone wall is reduced, compromising perfusion and dimensional stability over time.

Risk Assessment and Management

Proper planning prevents poor performance. Ideally, implant treatment planning involves the use of checklists and risk assessments to anticipate and mitigate adverse outcomes. An example of such a checklist is the 10 Keys for Successful Esthetic-Zone Single Immediate Implants.9 In addition to a patient-centered esthetic risk assessment, implant treatment planning should include the use of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) to determine the correct implant size and position, forward-thinking hard- and soft-tissue management during implant placement, and a purposeful provisional and final restorative plan. Another practical risk identification and assessment tool, the International Team for Implantology's SAC: Straightforward, Advanced, Complex classification system, provides an evidence-based framework to assess the potential difficulty of implant treatments.10 These tools can help to minimize hard and soft tissue complications that result from diagnostic and treatment errors. In addition, they can help to facilitate the early identification of complications when they arise, which enables treatment to be less invasive and more predictable, and they can aid in patient education and informed consent.

Periodontal and Prosthetic Challenges

So far, the emphasis of this article has been on implant position and bony dimensions. Although facial positioning of an implant negatively influences bone volume, esthetically, this typically manifests as a scarcity of soft tissue.

Recession around a natural tooth is defined as the apical migration of the gingival margin in relation to the cementoenamel junction. However, this definition is inconsistent for recession around implant-supported restorations, given the lack of reference points. Regardless of the reference points used, the apical migration of peri-implant marginal tissue is a common esthetic concern. The incidence of implant recession defects varies, ranging from 10% to 60%.11,12Among other causes, implants that are positioned or angulated too far facially create anatomical conditions that favor apical migration of the marginal soft tissues.

Marginal tissue migration around implants occurs as a result of interrelated factors, which include deficiencies in the bone, a thin soft-tissue phenotype, and inflammation. Implants that are too facially positioned can precipitate both hard- and soft-tissue deficiencies. The bony crest supports the supracrestal soft tissue at its base, typically 3.5-mm to 4.0-mm apical to the peri-implant margin. When an implant is placed with insufficient facial bone volume, it can result in bony dehiscences, which can predispose the site to soft tissue dehiscences. Thicker gingival phenotypes prevent soft-tissue involution by maintaining a sufficient thickness of healthy connective tissue, even with an inflammatory response.13 In thin soft-tissue phenotypes, an inflammatory process, whether stimulated by bacterial biofilm or mechanical trauma, encompasses a more significant portion of the connective tissue. Inflammatory loss of collagen can result in dissolution of the entire width of the connective tissue and subsequent apical migration of the tissue margin.14 These problems manifest as a loss of supracrestal soft tissue volume, and a soft-tissue problem requires a soft-tissue solution.

Strategies for Esthetic Management

The approach chosen from the perio-prosthetic continuum of treatment options for facially positioned implants naturally depends on the problem's severity. In cases in which an implant is positioned outside of the emergence of adjacent teeth, Zucchelli and colleagues recommend removing it.12 In cases in which the implant is within the emergence of adjacent teeth, soft-tissue augmentation is the treatment of choice. Prosthetically, treatment then focuses on planning a restoration that accommodates the implant position and minimizes the facial aspect. Treatment options include using angulated screw abutments, reducing the facial extent of a non-angulated healing abutment, and planning for cement- or screw-retained restorations with abutment/crown screw accesses on the facial surfaces. The following two cases demonstrate perio-prosthetic strategies for treatment.

Case Report 1

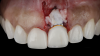

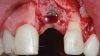

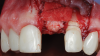

The patient in this case had undergone implant therapy at the site of tooth No. 9 and was restored with a cement-retained restoration more than 5 years prior. At presentation, the site demonstrated a peri-implant soft-tissue dehiscence that extended approximately 3-mm apical to the gingival margin of tooth No. 8. Thin and erythematous marginal tissue was evident at the zenith (Figure 2). The crown was removed, and a partial thickness flap was reflected using a papilla-sparing incision design. This revealed that the implant was positioned too far facially and that its body was visible through a very thin layer of bone (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The first objective of treatment was to minimize the facial extent of the emerging abutment and crown. To accomplish this, the facially positioned abutment and implant crown margin were both recontoured. The second treatment objective was to provide additional supracrestal soft tissue that would more adequately maintain the peri-implant margin. The tuberosity was selected as a donor site due to its dense, high-quality connective tissue, low propensity for shrinkage, and association with minimal patient discomfort. Once the graft was secured (Figure 5 through Figure 7), the flap was coronally positioned (Figure 8). After a healing period of 2 weeks, the margin of tooth No. 9 exhibited an ideal position in relation to its contralateral counterpart and demonstrated increased soft tissue thickness (Figure 9). Three months postoperatively, further healing had improved the esthetics and the position of the margin had been maintained (Figure 10).

Case Report 2

A patient presented for the restoration of an implant that had been placed at the site of tooth No. 9, which exhibited a residual soft-tissue deficiency and an undulating facial soft-tissue morphology (Figure 11). The objective of the treatment was to change the appearance and thickness of the facial soft tissue prior to crown placement to optimize the esthetics and prevent future soft-tissue dehiscence. After flap reflection (Figure 12), a graft was acquired from the patient's tuberosity to augment the supracrestal soft tissue (Figure 13). A volume-stable collagen matrix was then placed to further increase the thickness of the soft tissue adjacent to the implant body (Figure 14), and the flap was sutured closed (Figure 15). Following a 3-month healing period, a positive change in the soft tissue's morphology was apparent; however, its volume remained deficient when compared with that of tooth No. 8 (Figure 16). When the screw-retained crown was delivered, a second graft was acquired from the tuberosity and placed to further increase the volume of the supracrestal soft tissue (Figure 17 and Figure 18). A postoperative healing period of 4 months resulted in an ideal position of the margin of tooth No. 9 with regard to its contralateral counterpart as well as more natural looking soft-tissue morphology and excellent supracrestal soft-tissue thickness (Figure 19 and Figure 20). Eight months postoperatively, the position of the gingival margin and the thickness of the soft tissue had been maintained (Figure 21 and Figure 22).

Conclusion

Implant therapy requires forward thinking and robust pre-, peri- and postoperative risk assessment and monitoring. Implants that are positioned too far facially threaten the stability of the facial bone and soft tissue and hinder the predictable fabrication of esthetic crowns. These problems can be avoided with the use of CBCT-informed digital implant planning and a meticulous surgical technique. If soft-tissue deficiencies occur following implant placement, the treatment depends on the extent to which the implant is facially positioned. If the implant is positioned within the emergence of the adjacent teeth, a combination of soft-tissue grafting, abutment modification, and prosthetic accommodation can be leveraged to curtail future soft-tissue issues and reestablish an esthetic result.

Queries regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@broadcastmed.com

About the Authors

Michael Z. Lamb, DMD

Periodontics Resident

Lackland Air Force Base

San Antonio, Texas

Fadi K. Hasan, DDS, MSD

Diplomate

American Board of Periodontology

Private Practice

McLean, Virginia

References

1. Resnik R. Misch's Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 4th ed. Mosby; 2020.

2. Quirynen M, Lahoud P, Teughels W, et al. Individual "alveolar phenotype" limits dimensions of lateral bone augmentation. J Clin Periodontol. 2023;50(4):500-510.

3. Ganz SD. The reality of anatomy and the triangle of bone. Inside Dentistry. 2006;2(5):72-77.

4. Tan WL, Wong TLT, Wong MCM, Lang NP. A systematic review of post-extractional alveolar hard and soft tissue dimensional changes in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(Suppl 5):1-21.

5. Kan JYK, Roe P, Rungcharassaeng K, et al. Classification of sagittal root position in relation to the anterior maxillary osseous housing for immediate implant placement: a cone beam computed tomography study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011;26(4):873-876.

6. Huynh-Ba G, Pjetursson BE, Sanz M, et al. Analysis of the socket bone wall dimensions in the upper maxilla in relation to immediate implant placement. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21(1):37-42.

7. Araújo MG, Lindhe J. Dimensional ridge alterations following tooth extraction. An experimental study in the dog. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(2):212-218.

8. Buser D, Martin W, Belser UC. Optimizing esthetics for implant restorations in the anterior maxilla: anatomic and surgical considerations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004;19(Suppl):43-61.

9. Levine RA, Ganeles J, Kan J, Fava PL. 10 keys for successful esthetic-zone single implants: importance of biotype conversion for lasting success. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2018;39(8):522-530.

10. Dawson A, Martin WC, Polido WD, eds. The SAC Classification in Implant Dentistry. 2nd ed. Quintessence Publishing; 2022.

11. Thoma D, Alfonso G, Hämmerle CHF, Jung RE. Management and prevention of soft tissue complications in implant dentistry. Periodontol 2000. 2022;88(1):116-129.

12. Zucchelli G, Felice P, Mazzotti C, et al. 5-year outcomes after coverage of soft tissue dehiscence around single implants: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2018;11(2):215-224.

13. Zucchelli G, Mazzotti C, Monaco C, Stefanini M. Mucogingival Esthetic Surgery Around Implants. 1st ed. Quintessence Publishing; 2022.

14. Novaes AB, Ruben MP, Kon S, et al. The development of the periodontal cleft. A clinical and histopathologic study. J Periodontol. 1975;46(12):701-709.