You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

There are several barriers that prevent patient compliance and adherence concerning treatment. For example, a patient's preconceived beliefs about oral health and incorrect information gathered from outside sources may act as barriers to making a well-informed treatment decision.1Educating patients in order to increase comprehension and motivation is one of the many goals a dental hygienist faces within patient care. Patient education not only leads to increased patient comprehension but plays a direct role in patients' compliance with treatment.2

Currently, dental hygienists use visual aids, such as the analogue periodontal chart and digital radiographs, to illustrate individual patient probe depths and bone loss. While these methods are effective, they may be unfamiliar to patients and difficult to synthesize into understandable facts.3 Research has shown that the use of multimedia methods for patient education yields a higher level of patient comprehension.4 Unlike the traditional periodontal chart, the use of digital scan technology provides accurate gingival recession measurements and produces presentable visual images of the periodontal data acquired.5 Images acquired through a digital scan of the gingival tissue can be used as visual aids to enhance the explanation of each patient's individual periodontal status and promote patient involvement.6 Owing to the high prevalence of periodontal disease and its effects on overall health, the United States Department of Health and Human Services has declared that improving practitioner-to-patient communication on periodontal disease and increasing patient health literacy is a vital step in the betterment of the oral health status of American adults.7 Currently there is a lack of research on the effectiveness of a 3D intraoral scan used as a personalized visual aid for periodontal disease education.

METHODS

Participants

This study was implemented in a private dental practice setting because of its accessibility to the iTero Element scan technology that was used for the intraoral scan. The private practice where the study was conducted has a database of approximately 1,000 patients. To achieve a confidence level of 95% and confidence interval of 21.7, a sample of 21 participants was needed.

A randomized controlled method was employed through the use of the private practice's database. The population was chosen through the study's inclusion and exclusion criteria, and participants were invited to enroll in the study on a volunteer basis.

Inclusioncriteria for participation in the study were a history of periodontal disease with clinical attachment loss measurements of at least 5 mm, at least 2 mm of bone loss visible on radiographs, gingival recession of 2 to 3 mm, and at least five pocket depths of 4 mm or greater. Participants had to be at least 21 years of age and have English as their primary language, with access to email. Participants were also required to be existing patients of the private practice. Exclusion criteria included previous formal dental education.

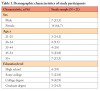

The study population (N = 21) consisted of 14 women and 7 men. Comparative research used larger participant samples ranging from 50 to 875 participants.1,8-11 For pragmatic purposes, the principal investigator (PI) recruited 21 participants to meet the minimum confidence level of 95%. Participants were assigned to an experimental group (n= 11) or a control group (n = 10) through an online random number generator. Age was split into five different ranges (21-25, 26-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55+ years). Within these age ranges, 9.5% (n= 2) participants were in the 26 to 34 years range, the lowest age group represented, while 33.3% (n= 7) of participants were in the 55+ years age group, representing the largest participant population in the study. The majority of participants (42.9%; n = 9) indicated that they had a college degree, while 19% (n= 4) indicated that they have a high school degree. See Table I for full list of participant demographics.

Standard Protocols, Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Approval was obtained from the Eastern Washington University Institutional Review Board, and informed consent from each participant before the study was obtained (see Appendix A1, A2). Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. In order to ensure confidentiality, participant information was de-identified before data were analyzed, and participants were given subject identifiers.

Study Design and Procedures

This research study used a parallel experimental quantitative research design, with pre-tests and post-tests administered to study participants in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the intraoral scan as a visual aid for demonstrating periodontal recession and risk. Two groups were evaluated for the study.

The control group received a periodontal evaluation presentation with a 2D periodontal chart, and the experimental group received a periodontal evaluation presentation with a 2D periodontal chart with the addition of a 3D scan of their teeth and gingiva showing periodontal recession. The iTero Element scan (Figure 1) was used to acquire a 3D intraoral scan of the teeth and gingival tissues. The experimental group also viewed a time lapse of Dentoform (Henry Schein) (model teeth and gingival tissue) recession using the iTero Element's TimeLapse demo mode (Figure 2). The TimeLapse demo mode function on the iTero Element is a preset function created by iTero to demonstrate gingival recession that may occur within a 6-month period. Owing to the limited time allotted for this study, the iTero Element TimeLapse demo mode was used to illustrate progression of recession. Using the preset demo mode function ensured all experimental group participants received the same gingival recession progression demo. The PI presented to both groups to ensure continuity of presentation content, and a script was used to ensure each group participant received the same presentation (see Appendix B and Appendix C). The methods used for data collection included the use of a pre-test with the self-efficacy Ask, Understand, Remember Assessment (AURA) Likert-scale instrument (see Appendix D). The AURA survey contains questions regarding communication self-efficacy of periodontitis diagnosis and treatment. The pre-test also contained the Protection Motivation Survey (PMS), which comprises seven sliding-scale questions evaluating patient periodontal disease risk literacy (see Appendix D). Two post-tests were given (see Appendix E and Appendix F). The post-test administered to the control group contained the same AURA and PMS questionnaires, with the addition of four Likert-scale questions regarding participant experience and the understandability of the 2D periodontal chart as a visual aid. The post-test administered to the experimental group also contained the same AURA and PMS questionnaires, with the addition of eight Likert-scale questions regarding understandability and participant experience with the 2D periodontal chart and 3D intraoral scan. Each post-test was given directly after periodontal evaluations were complete. A second post-test was given via email 1 week after the initial presentation with AURA and PMS questionnaires only, to measure comprehension data.

Each presentation (control and experimental) was allotted 90 minutes from the start of the pre-test to the completion of the post-test. Upon completion of the pre-test, each participant was shown to the operatory set-up for either the control presentation or the experimental presentation. After the completion of the presentation (control or experimental), participants were allowed to ask the PI questions regarding their periodontitis status, treatment options, and prevention strategies. Directly after the presentation and question time, a paper post-test was completed by each participant. The experimental group's post-test was identical to the pre-test, with the addition of eight Likert-scale questions regarding the patient experience with the 3D iTero Element scan and 2D periodontal chart. The control group's post-test contained the addition of four Likert-scale questions regarding the patient experience with the 2D periodontal chart as a visual aid. In order to test long-term comprehension and patient experience, 1 week after the initial study, a post-test SurveyMonkey link, corresponding to each group, was sent out via a secure email.

Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS version 2.4 software was used to collect and analyze the data. All participants (100%; N= 21) completed all three surveys (pre-test, post-test, emailed post-test). The additional questions added to the first post-test surveys, which tested for patient experience/comprehension with the periodontal chart and the 3D intraoral scan, were completed by only 85.7% (n =18) of participants.

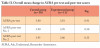

Upon statistical analysis, it was shown that participant communication self-efficacy (AURA survey) in the 3D intraoral scan experimental group (n = 11) did not statistically improve compared with the control group (n= 10) (Table II and Table III). After breaking down each AURA question for comparison and statistical change in score from pre-test to post-test, there was still no statistical significance found. Similarly, when evaluating the quantitative data for change in risk-literacy (PMS questionnaire) between the control and experimental groups, no statistical significance was found between average PMS scores for pre- and post-tests and individual questions (see Table IV and Table V). Among the whole study population, statistical significance (P< .03) was found between an elevated PMS post-test No. 1 score and elevated Experience Post-test score (both taken directly after interventions). This statistically significant correlation indicates that the addition of periodontal disease risk education and explanation of a patient's periodontal chart is beneficial to a patient's perceived comprehension and motivation. Statistical significance (P< .03) was found between the control group post-test No. 1 and the questions regarding patient experience (taken on the day of the study), and no statistical significance was noted between control post-test No. 2 (taken 1 week after the study) and the patient experience questions (taken on the day of the study). Likewise, there was no statistical significance found for the experimental group's PMS post-tests and the patient experience questions.

DISCUSSION

At the end of each session with the control (n= 10) and experimental (n= 11) groups, the PI left time for participants to ask questions concerning their periodontal disease risk and clarify any information presented. Participants from both the control and experimental groups asked questions that revealed a higher level of comprehension. The PI fielded questions concerning the bacterial cause of periodontal disease, the genetic and oral systemic link, and the risks of not adhering to homecare suggestions. In the experimental group, the addition of the 3D intraoral scan produced more questions concerning the causes of gingival recession and why gingival tissue cannot grow back after recession has occurred. The 3D intraoral scan produced a deeper level of discussion regarding how periodontal disease causes gingival recession and what prevention measures could be taken to prevent disease progression, while the control group did not ask higher-level questions pertaining to treatment options and home care. This anecdotal finding concerning communication relates to providing effective communication for better periodontal health outcomes within the American adult population.12 Discussion within the control group did not produce any questions concerning periodontal recession or prevention measures that may reduce clinical attachment loss. Both groups were concerned about their periodontal disease after periodontal disease education was completed and were fixated on the concept of bone loss. The PI noted that the majority of participants from both the control and experimental groups voiced desire to change home care habits because they did not want to experience bone loss from periodontal disease. Owing to the experimental group's higher level of questioning, the PI sent out a questionnaire (Table VI) to participants from the experimental group 1 month after the study to evaluate how the 3D intraoral scan impacted their thoughts on periodontal disease and their current home care routine. The questionnaire was completed by six of the experimental group participants.

Conversation between providers and participants was enhanced by allotting time for periodontal disease education and discussion, and the addition of the 3D intraoral scan resulted in a deeper level of critical thinking among participants in the experimental group concerning the etiology of periodontal disease and how prevention and treatment recommendations impact periodontal health.

Currently 3D intraoral scan technology is not being utilized by dental hygienists as a way to visually track gingival recession or as an interactive personalized visual aid during patient education. For a student of dental hygiene, learning how to successfully communicate with a patient is foundational. According to the self-efficacy theory, increased practice of complex educational concepts (i.e., instrumentation, patient education, treatment planning) leads practitioners to become more confident in their ability to perform these actions and behaviors.13 Intraoral scan technology, as a personalized visual aid demonstrating periodontal recession, may be used by dental hygienists to help create discussion points regarding disease diagnosis, treatment options, and home care suggestions. In order for dental hygienists to be contributing practitioners within the rapidly evolving world of digital dentistry, training and competency with the 3D intraoral scan is needed.

Patient Risk-Literacy

Before the implementation of this study,the PI theorized that the addition of a personalized 3D intraoral scan of a patient's gingival tissue would increase understanding of periodontal recession and help clarify the meaning of the patient's periodontal chart and disease status. This improved understanding would lead to increased risk literacy of periodontal disease and open channels for robust conversation between the patient and his or her provider regarding the patient's periodontal disease status and treatment. The results of this study showed no statistical significance for risk-literacy improvement in either the control (with no 3D scan) or experimental (with 3D scan) group. In a similarly designed study with a larger sample size, Asimakopoulou et al11 found that an individualized risk communication session between patient and provider increases a patient's risk literacy concerning their periodontal disease. While Asimakopoulou et al found significant change within their experimental group's risk literacy, they also saw significant change within their control group's risk-literacy scores.11 These researchers concluded that both routine (control group) and individualized (experimental group) periodontal education with patients positively impacts patients' perception of their disease.11 The study conducted by Asimakopoulou et al used a significantly larger study population (N = 102) than the present study, and therefore significant difference in scores was seen between the control and experimental groups.11

Patient Communication Self-Efficacy

A patient's perceived confidence in their ability to communicate with their provider (communication self-efficacy) plays a large part in how they make decisions regarding their health. Effective communication between provider and patient leads to increased patient comprehension of their disease and an increased ability to ask pertinent questions concerning their health.14,15 In order to evaluate the impact of the 3D intraoral scan as a visual aid for the enhancement of a patient's communication self-efficacy, the PI used the AURA survey within a pre-test and two post-tests. Before the study, the PI anticipated that using the 3D intraoral scan as a visual aid during periodontal disease education would open lines of communication between provider and patient regarding the risk of disease and treatment, thus increasing patient communication self-efficacy. The PI expected a higher AURA survey score for those who received periodontal disease education with the addition of a 3D intraoral scan as a visual aid (experimental group) compared with those who did not have a 3D intraoral scan as a visual aid (control group). No statistical significance was found within the control group or experimental group in terms of scores from pre-test to post-test. Because neither group demonstrated any significant change from AURA pre-test to post-test, the PI attributed the results of this study to the small population sample size, and high education level among the population sampled. As stated above, similarly designed studies that found statistical significance among control and experimental groups had sample sizes of 50 to 875 study participants.1,8-11 The present study had a small sample size of 21 participants, with the majority (57.2%; n = 12) reporting an education level of college degree or higher. Populations with low education levels (less than a high school degree) are the most likely to have low health literacy (Health.gov). In their study concerning health literacy, Clayman et al14 found that participants (n= 100) with low health literacy scores scored low on the AURA assessment (P< .05). Seeing significant changes in AURA survey scores may not have been achievable because the population of this study possessed a high education level. Both the control (n= 10) and experimental (n= 11) group had a high mean baseline AURA score of 3.80 and 3.81, respectively. Minor changes were seen between pre-test and post-test, but none with any statistical significance.

The high level of education (college degree or higher) in the study population contributed to a high baseline score for the PMS (risk literacy) and therefore made it difficult to observe statistical significance from pre-test to post-test. A low level of risk literacy is correlated with a low level of education. For results to be more generalizable, the education level among participants would need be evenly distributed. The limitations of this study should be considered when conducting future research.

RECOMMENDATIONS/SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

During the implementation of the study, the PI noted ways in which the study could be enhanced for future research. The PI suggests using two control groups and one experimental group in order to better evaluate the effectiveness of the 3D intraoral scan and visual aids as educational tools. Participants from the first control group would receive verbal periodontal education concerning their periodontal chart, those from the second control group would receive verbal education with the addition of seeing their periodontal chart, and those from the experimental group would receive verbal education along with seeing their periodontal chart and 3D intraoral scan. A larger sample size is also encouraged for future research, as well as recruiting examiners who do not have previous affiliation with the patients enrolled in the study. This would ensure a more accurate AURA score and eliminate participant bias. The PI also suggests conducting the study over a 1-year time frame in order to test adherence to home care suggestions, and to allow two 3D intraoral scans to be performed. These two separate scans could be compared and shown to participants in order to show the progression of their own gingival recession. These recommendations may improve future research and unveil how effective the 3D intraoral scan is concerning patient risk-literacy education and communication self-efficacy improvement.

LIMITATIONS

Data were collected from a small convenience sample size of 21 participants. This small sample size was significantly less than that of comparative research and makes finding statistical significance and correlations between control and experimental group data less generalizable. A limitation to the results of the AURA survey is possible participant bias. Study participants were current patients of Kois Dentistry, which is the workplace of the PI. The study participants have known the PI for several years, and therefore participant pre-test AURA scores may have been inflated by the fact that participants already experience open communication concerning their periodontal disease and feel comfortable asking questions of their provider (the PI). This may have contributed to the finding of no statistical significance between the control and the experimental groups' pre-test and post-test scores.

CONCLUSION

Further research on the effects of the 3D intraoral scan on patient risk literacy and communication self-efficacy should continue to be conducted and evaluated. Increasing the periodontal disease knowledge level of a patient alone does not equal patient behavioral change, nor does it equal patient adherence to treatment suggestions. Patients who feel comfortable stating opinions and asking questions tend to have better overall health outcomes.15 Using the 3D intraoral scan to help inspire constructive talking points between provider and patient is one way in which this tool could enhance treatment adherence success rates. Knowing the stage of change a patient is currently in may also be helpful in determining how receptive a patient is to the intraoral scan. Providing avenues for patients and providers to successfully communicate regarding the patient's periodontal disease is needed in order for successful treatment adherence and patient behavioral change to occur. In order to understand and appreciate 3D intraoral scan technology in the field of dental hygiene, continuing education courses concerning the use and applications of this new technology should be developed.

REFERENCES

1. Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people's health care decisions: Is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making.2005;25(4):398-405.

2. Collins SM. An overview of health behavioral change theories and models: interventions for the dental hygienist to improve client motivation and compliance. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene.2011;45(2):109-115.

3. Hughes B, Heo G, Levin L. Associations between patients' understanding of periodontal disease, treatment compliance, and disease status. Quintessence Int.2018;49(1):17-23.

4. Winter M, Kam J, Nalavenkata S, et al. The use of portable video media vs standard verbal communication in the urological consent process: a multicentre, randomised controlled, crossover trial. BJU Int. 2016;118(5):823-828.

5. Corraini P, Baelum V, Lopez R. Reliability of direct and indirect clinical attachment level measurements. J Clin Periodontol.2013;40(9):896-905.

6. Stenman J, Wennström JL, Abrahamsson KH. Dental hygienists' views on communicative factors and interpersonal processes in prevention and treatment of periodontal disease. Int J Dent Hyg.2010;8(3):213-218.

7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Oral Health Coordinating Committee. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Oral Health Strategic Framework, 2014-2017. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(2):242-257.

8. Brock TP, Smith SR. Using digital videos displayed on personal digital assistants (PDAs) to enhance patient education in clinical settings. Int J Med Inform.2007;76(11-12):829-835.

9. Austin PE, Matlack R 2nd, Dunn KA, et al. Discharge instructions: do illustrations help our patients understand them? Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(3):317-320.

10. Cleeren G, Quirynen M, Ozcelik O, Teughels W. Role of 3D animation in periodontal patient education: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol.2014;41(1):38-45.

11. Asimakopoulou K, Newton JT, Daly B, et al. The effects of providing periodontal disease risk information on psychological outcomes - a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(4):350-355.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in oral health. https://www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/oral_health_disparities. Updated February 5, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2021.

13. Jenkins LS, Shaivone K, Budd N, Waltz CF, Griffith KA. Use of genitourinary teaching associates (GUTAs) to teach nurse practitioner students: is self-efficacy theory a useful framework? J Nurs Educ. 2006;45(1):35-37.

14. Clayman ML, Pandit AU, Bergeron AR, Cameron KA, Ross E, Wolf MS. Ask, understand, remember: a brief measure of patient communication self-efficacy within clinical encounters. J Health Commun.2010;15(Suppl 2):72-79.

15. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Ware JE Jr. Characteristics of physicians with participatory decision-making styles. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(5):497-504.