You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Despite improvements in oral health prevention and treatment, many individuals lack adequate access to oral health services and consequently experience oral health disparities.1 Integrating preventive oral health services into primary care has expanded over the past decades, yet, has faced challenges.2-4 In a recent scoping review of medical-dental integration, various models of integration were described; however, none described the integration of dental hygienists into primary care medical teams.5 More commonly, the term medical-dental integration has been used to describe the delivery of preventive oral health services by medical providers/teams (e.g. caries risk assessment, oral health examination, fluoride varnish application and a coordinated dental referral) at medical visits.2, 6, 7 Patients have direct access to dental hygienists in 42 states.8 Most literature describing dental hygienists working in non-traditional settings includes examples of employment in school settings and/or public health environments.9,10 There are emerging descriptions of the dental therapists' experience,11-13 but there is a paucity of literature describing or evaluating models that integrate dental hygienists into medical teams in primary care practices.

Colorado has been testing models of integrating dental hygienists into medical teams with the goal of expanding access to dental services for populations who have limited access to dental care due to insurance status, living in dental professional shortage areas and other barriers. Over the past decade, the Delta Dental of Colorado Foundation (DDCOF) has supported medical-dental integration, beginning with the co-location of direct-access dental hygienists into medical practices (2007-2011).14 In 2014 DDCOF expanded their original approach to a new model which integrated dental hygienists directly into medical care teams, allowing for the full scope of dental hygiene services to be delivered within the medical practices. Using a level-of-integration scale of one to six, where a level five or six includes having a common workspace, support staff members, electronic health record, workflows and treatment goals,15 dental hygienists were integrated at a level of five or six with coordinated referrals to co-located dentists (when available) or outside community dentists. The purpose of this study was to explore dental hygienists' perceptions of working as a member of an integrated medical team and patients' perceptions regarding medical-dental integration (MDI) care. Factors impacting implementation of MDI, the level-of-integration of dental into medical teams, and how MDI expanded access to dental services were also examined.

Methods

This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, Protocol 15-0263. A concurrent, mixed-methods approach was used; qualitative interviews were conducted with the MDI dental hygienist participants and a quantitative survey was administered to patient-participants who had received MDI care. Participants in each approach were independent, therefore both approaches were considered primary and analyzed independently. Results were integrated in the interpretation phase.

Key Informant Interviews

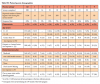

A semi-structured interview guide to explore dental hygienists' perceptions related to MDI was developed by the study team (Table I). A qualitative research expert piloted the interview guide and refined it to improve its validity and fit for the setting. All dental hygienists from the healthcare organizations participating in the MDI (n=15) project were invited to complete a semi-structured telephone interview during a two-month period in 2018. At that point in time, organizations were 18-24 months into MDI implementation. Each MDI dental hygienist received up to four email-invitations over a 2-month period. Two investigators conducted all interviews with only the interviewer and interviewee present. Interviews lasted approximately 30-60 minutes. Summary notes were made following each interview and reviewed by the study team during analysis. All interviews were audio-recorded and securely sent for verbatim transcription by an independent professional transcription service. No compensation was provided for participation.

Content analysis was used to identify themes and subthemes within and across all interviews.16 A hybrid of both deductive and inductive approaches from data collection throughout the analysis was applied.17 Themes and subthemes were formulated using team-based analysis. Trained qualitative data analysts iteratively read transcripts, individually coded three transcripts to develop and refine both the codebook and coding approach and met to discuss emergent themes. One analyst was a content expert and provided subject matter context to the evaluation. The team compared the individually coded text, discussed code definitions, and edited codes to accurately describe these data. All remaining transcripts were then coded using these agreed upon definitions.

Open and axial coding of transcripts were used to form the basis of analysis: open coding included labeling concepts and defining and developing categories based on the interview data and axial coding was used to confirm and explore relations between transcripts by applying a priori concepts to the data.18 The analyst team met regularly to check biases and understand emergent themes and intercoder reliability was confirmed. A software program (ATLAS.ti 7.0; Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used to complete coding and analysis.

Patient Satisfaction Survey

The parents of children and adult patients seen by the integrated dental hygienists in the MDI project (2016 and 2018) were asked to complete a paper survey (English/Spanish). The MDI clinical teams were instructed to ask all patients seen by the dental hygienist within the specific time frame of the study, to complete the survey and place it in an anonymous collection box/area. Surveys were written in English/Spanish and did not include participant identifiers. Six practices were excluded from the survey collection process: one practice exclusively served refugee patients (language/translation barriers), two school-based practices (parents did not attend visits), two practices had transitioned to a co-located model, and one practice had a dental hygienist on leave.

The survey was developed using questions from a previous study on co-location care satisfaction14 and measured participants' perceptions regarding MDI care. The 20-item survey was piloted in a convenience sample of participants and then refined prior to administration. Four-point Likert scales were used to measure perceptions: satisfaction (extremely to not-at-all satisfied), barriers (big problem to not a problem) and attitudes (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe baseline socio- demographics of the study population, and baseline and follow-up variables. Data are presented as means and ranges for continuous data and percent of whole for categorical data.

Results

The 15 participating MDI health care organizations included federally qualified health centers (n=6), nonprofit practices (n=5), school-based health centers (n=2), and private for-profit practices (n=2). A total of 17 dental hygienists employed as part of the MDI project agreed to participate, only one declined. Dental hygienists practicing in the MDI settings provided a variety of services including caries risk assessments, fluoride varnish applications, sealants, dental radiographs, scaling and root-planing. Characteristics of the MDI health care organizations are shown in Table II.

Qualitative Findings

Interview themes

Three major themes emerged as factors impacting successful medical-dental integration. Individual-level impacts included dental hygiene skills and personal characteristics. Practice-level impacts related to leadership support, workflow support (billing and front office/medical assistant (MA) support), scheduling DH visits, patient volume, and a lack of onsite dentist. The system-level impacts included areas such as insurance policy limitations and insufficient reimbursements. Overall, the participant perceptions did not differ based on the type of health care organization in which they were employed.

Dental hygiene skills and personal characteristics

Certain dental hygiene skill sets and characteristics emerged as important for MDI success. Integration into the medical system was universally new to the participants and they possessed a range of professional skills and personalities. When asked what characteristics were necessary for this kind of work, participants replied that it was important for dental hygienists to be adaptable, problem-solvers, good negotiators, and able to work independently yet also build professional and clinical relationships. Participants also emphasized that willingness to "learn-by-doing" was required for success. One dental hygienist summarized:

"It's a hard position…I am a one-person dental office, less the dentist, because I literally do everything, except for the scheduling. You have to be someone who is willing to be very thorough, be willing to switch up doing something at the drop-of-a-hat, be able to ‘multitask on steroids."

Participants also expressed the importance of a being willing to work with challenging patient populations. Many of the MDI practices cared for vulnerable populations which required the dental hygienist to be compassionate and willing to meet the individual needs of the patient population.

"…you definitely want someone here who has compassion for the demographic of people that we work with-a lot of homeless men. And I specifically work with foster care kids. I see a lot of child abuse and neglect."

Leadership support

The individual health care organization's support of the integration of the dental hygienist into the medical teams was essential. At medical practices where integration was successful participants described a supportive practice-site leader; within the practices with failed integration, participants described a lack of clinic leaders' support for the dental hygienist and/or the MDI concept. Successful practice leaders provided enabling/enforcing support such as clerical staff to schedule dental hygiene patients, billing staff to bill for the dental hygiene services provided, and medical assistants to screen patients who were eligible for integrated care and/or to complete warm hand-offs to dental hygienists for same-day services. One participant from a successfully integrated practice shared how initial challenges were solved through the practice leadership.

"It took almost 3 months to get her [a receptionist] trained and willing to just change the schedule…everyone is so resistant to doing additional work…the only way to get that done was to have leadership tell them they have to do it."

Participants reported that when a practice lacked leader support for dental hygiene appointment scheduling and billing, it appeared to impair the MDI process. One participant from a practice struggling with the MDI process stated that she had to do her own scheduling.

"The dental program was not a priority for anyone...the lady who was in charge of scheduling…she really didn't care much about it and her staff, which is the front desk, they didn't care either."

Anecdotally, this particular practice's chief operating officer ended their MDI project work citing that the dental hygienist did not see enough patients.

Workflow support

Another practice-level theme that influenced the dental hygienists' integration was the delegation of work to other team members to support dental hygiene workflows. When work was delegated to other team members and the leadership was able to motivate staff to support integrated dental hygiene care, the MDI practice was more likely-to-succeed. For instance, when leaders delegated dental screening tasks to medical assistants and motivated them to complete these added tasks, practices were more successful with completing integrated dental hygiene visits. Also, at successful practices, medical assistants also helped check in DH patients and monitor patient flow. A participant from one successful MDI site described a strong working relationship between dental and medical staff.

"We all work really well together. I can go straight to the MAs and MD and just tell them what we need and…if they see where there is a patient that needs [dental hygiene] care right away, they can come straight to us, and we are able to see that patient immediately."

Furthermore, this practice developed a check-in process that included each medical assistant routinely mentioning to their patients that dental hygiene services were available and "…if the patients are willing to be seen, we are able to see them. That isn't a problem for us." This was in contrast to what was experienced at practices with less-successful integration. For example, one participant from a practice that struggled with integration stated, onboard to let the patient know that there is a hygienist in the office, and they can have their dental hygiene services here. In my opinion, I seem to be put as the low man on the totem pole."

However, a participant from a practice that had successfully integrated the dental hygienist into their setting shared,

"The longer I was there, and the more people got accustomed to me, the more I felt a part of the team."

Also, a significant barrier to dental hygiene integration was the expectation that it was incumbent upon the dental hygienist (at some sites, sole responsibility) to fit the dental practice needs, billing, and identification of new patients, into the established medical practices' processes, patients, and practice billing structure and procedures. Yet, some practices had leaders who supported a culture that promoted the medical staff and providers working with the dental hygienist and made incremental changes in their culture to increase staff awareness and held them accountable for their role in making MDI successful (a "continuous improvement culture"). The ability of the medical practice to implement practice change incrementally appeared to be associated with successful integration. One participant shared,

"We have weekly clinic meetings and we have biweekly staff meetings and bring up issues that we have, as well as the supervisors also discuss what issues that we're having that aren't working…[and] need to be dealt with."

Dental hygiene appointments

Participants reported a range of experiences with scheduling patients across the practices. The act of scheduling new and returning dental hygiene care visits was a key factor in how the participants perceived successful/unsuccessful integration. The MDI practice benefited when the administrative staff scheduled the dental hygiene patients. One example was a MDI within a school-based health center practice, co-located where children spent their days in the classroom. In such settings, the dental hygienists could more easily see patients,

"…[I have] a list of kiddos I can pull from class…being able to schedule and do that from the get-go was a huge thing that played a huge role in it for families [to access dental care at her site").

Workflow support in regard to scheduling dental hygiene care visits was mentioned by other participants as important factors to MDI success.

Low patient volume

Participants working in small practices with low patient volume faced particular challenges including the frequency of low-patient visit days impacting the opportunities for MDI visits, combined with a high no-show rate. One DH shared,

"Well, it was slow. It was real slow; a typical day, three patients, probably if lucky enough, 4 to 5….and there would be days that I had nobody…and there were a lot of patients who would not show up."

Lack of an onsite dentist

Another practice-level challenge was not having an onsite-dentist for restorative dental services. A few of the participants expressed that they believed it was a unique and exciting opportunity to practice independently from dentists, however, most participants described difficulties associated with not having an onsite dentist. This created a barrier for patients to access restorative dental care and was particularly concerning to the participants. Low-income and patients with emergent needs were noted to be particularly vulnerable. One participant stated,

"…sending children to off-site clinics is kind of a barrier to care because it's hard for families to get to the clinic where the dentist is."

Challenges for patients to receive dental care from a dentist also included a lack of capacity on referral dentists' schedules to absorb the dental hygienists' patients. One participant noted that,

"…there are not enough dentists providing the actual dental care, even with a ‘backdoor' clinical relationship between the dental hygienist and dental practice."

Finally, participants described challenges with practicing solo and not having a dentist, "…just to run things by" to help make a clinical determination or, for instance, to approve their use of anesthesia or nitric oxide with a periodontal patient.

Insurance eligibility

Though it was mentioned less frequently, the need to verify the patients' insurance status was described as a barrier for several MDI practices. In Colorado, medical and dental insurance portals are separate. Additionally, medical claims are traditionally paid by diagnosis and dental claims are paid by procedure (with frequency limitations). Since few of the front office administrators had started this program with in-house knowledge or experience with handling dental insurance, MDI practices had to invest time into teaching the staff how to check and confirm dental insurance eligibility and coverages for patients, or else the dental hygienists in each MDI practice were required to complete these activities.

Dental insurance reimbursement

Some participants described frustration with providing services that were eventually not reimbursed. A variety of reasons were cited for denying dental claims including dental insurance benefit changes, lack of expertise in accurately submitting the insurance claims, providing services prior to coverage, and changes in coverage. Some participants stated that keeping up with benefit changes took time away from providing direct care and was a frustrating aspect of the MDI project. One participant expressed, "I wish that Medicaid would settle down. They just change the rules all of the time."

Quantitative Results

Patient and parent surveys

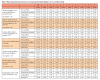

A total of 1,196 patient-participants were provided integrated dental hygiene care during the months surveyed in the participating MDI practices. One-third of the participants (n=390) completed the paper survey. Respondent demographics are shown in Table III. In general, the respondents favored the MDI care they received. A majority reported being satisfied with the care (100% extremely/very), more likely to recommend the MDI practice with a dental hygienist to friend/family than one without (95% strongly agree) and were likely to return to the dental hygienist in the future (95% strongly agree). Most reported that they were more likely to take self/child to a dental hygienist located within the medical office than outside (75% strongly agree). More than three-quarters (78%) agreed that MDI care was more convenient than traditional care. Patient and parent perspectives regarding MDI care are shown in Table IV.

Regarding barriers to utilizing dental hygiene care in a MDI setting, a little more than one half of the respondents (52%) reported that it was problematic that the dental hygienist was not able to fill cavities. General barriers to receiving MDI care are shown in Table V.

Discussion

In this mixed-methods investigation into the perceptions of dental hygienists and patients/parents participating in medical dental integration programs, both the dental hygienists and patient/parents endorsed the benefits of integrated dental hygiene services. Dental hygienist participants reported various, but not unsurmountable, barriers to providing integrated care. Dental hygienists working in this non-traditional MDI model were enthusiastic about providing care to an underserved population, however they identified challenges and reported that working in this non-traditional setting required unique skills. These skills have been similarly described in an investigation of extended-function dental hygienists by Delinger et al.9 Dental hygienists working in an extended function capacity needed to be entrepreneurs with good communication skills, demonstrate the ability to network, problem solve, think critically, and possess strong administrative skills.9 Patient and parent satisfaction levels were similar to perceptions previously reported by recipients of dental hygiene services co-located with medical providers.14

Medical-dental integration studies reported in the literature have primarily focused on preventive oral health services delivered by medical providers/teams such as caries risk assessments, oral health examinations, fluoride varnish applications and coordinated dental referrals.2,6,7 Barriers reported by medical teams relating to the provision of these services in the medical office setting have been almost exclusively at the provider- or practice-levels.3,4 Additional barriers have included lack of training,3 and lack of sufficient time to plan for change or the logistics of providing these services.3, 4

In comparison, this study employed a unique model of oral health promotion in the medical setting and provides new results to the literature. The embedded dental hygienists in this MDI project provided full-scope dental hygiene care within the medical practice. While some of the reported practice-level barriers were similar regardless of the approach, such as lack of efficient workflow/logistics, it is noteworthy that lack of time did not emerge as a theme in this study. Rather, a low patient volume was mentioned by some participants. This may be due to the finding that medical providers providing oral health services commonly focus on young children and already incorporate oral care into the existing medical care visit,2,6,7 whereas the embedded dental hygienists in MDI practices provided care to a broader spectrum of patients and the appointments were separate from medical visits.

Dental hygienist participants in this study also commonly mentioned the healthcare organizations' lack of experience with providing dental services such as unfamiliarity with dental insurance and lack of leadership support, issues that were less commonly reported in investigations of medical providers providing preventive dental services themselves. Regardless of the approach, barriers to providing preventive oral health services in the medical office exist but are surmountable. Evidence supports the efficacy of oral health promotion by medical providers on reducing dental disease,6, 7 however, more investigation is needed to explore the impact of integrating dental hygienists into medical care teams on oral health outcomes.

System-level challenges, including insurance payment policy restrictions, have been cited in the literature when describing the barriers to providing dental hygiene services outside of traditional dental practice settings.9,19 Dental hygienists interviewed in this study shared that insurance barriers included not being able to bill under a medical providers' license (which led to limited reimbursement) as well as providing dental hygiene care within the constraints of dental-insurance-recall-frequencies. These arbitrary con-straints limited the type of care provided and the frequency of the dental hygiene care visits despite the risk for oral diseases. In a survey of expanded-access dental hygienists in Oregon, barriers to working outside of traditional dental practices included challenges with insurance reimbursement and difficulty obtaining a collaborative agreement/cooperating facility.19 An investigation of direct-access dental hygiene care in Kansas reported similar barriers in addition to dental hygienists not being able to directly bill for services rendered.9 Participants interviewed in this study also mentioned reimbursement concerns including the lack of dental insurance in addition to challenges in keeping appraised of dental-benefit updates.

Study participants rarely mentioned challenges with establishing a collaborative agreement with a dentist. More commonly, dental hygienists in this study noted challenges in finding dentists to refer patients with untreated dental decay. This barrier has also been cited in previous work investigating barriers to medical providers providing preventive dental services.4 While integrating dental hygiene care into medical settings expanded access to dental services, system-level barriers persisted including disparities in dental insurance coverage and differences in how medical and dental claims are reimbursed. Comprehensive healthcare insurance, which includes both medical and dental coverage, has the potential to reduce these barriers.

Findings from this study are similar to those describing behavioral health integration in medicine. Specifically, factors cited to be important to behavioral health integration include having an empowered leadership team, integrated care processes, and workflows.20 In a qualitative study of integrated behavioral health specialists, similar facilitators and barriers were identified, including the importance of leadership support for building new models, the benefits of any prior experience with integration, and the importance of support from others doing similar work.21-23 Developing efficient workflows was also cited by the dental hygienist participants interviewed in this study and have been noted as critical to the successful of behavioral health integration.

This study adds to the literature describing stakeholders' perceptions with integrating dental hygienists into medical care teams. Strengths include reporting comprehensive perceptions of dental hygienists working in a variety of MDI healthcare systems. Limitations of this study include a lack of generalizability. Although 42 states allow direct-access to dental hygienists, practice acts vary state-by-state so the level of independent care provided in Colorado may not apply to all direct-access states. While patients/parents were intentionally surveyed 18 months into their practices' participation in MDI, patients' experiences varied as each practices' approach to the MDI model were customized based on the practice size and population. The participating dental hygienists reported the number of patients seen during the month that the survey was collected, and the authors cannot confirm that all patients received a survey. Additionally, while the survey had been used previously in a similar study,14 the instrument was not validated. Also, reporting bias may have impacted the responses as well as missing data.

Conclusions

Results from this study support that this innovative approach of integrating dental hygienists into medical practice settings provided patients with a favorable alternative access to oral health care services. Challenges to this medical-dental integration approach included dental insurance limitations, challenges with integrating the dental hygiene care workflows, limitations on the dental hygienists' ability to restore decay, and a lack of available dentists to provide restorative care to vulnerable populations. However, many of these challenges were surmountable. Building a dental hygiene workforce ready to deliver integrated care is warranted for the future.

Disclosure

Delta Dental of Colorado Foundation (DDCOF) provided the funding for the Colorado Medical-Dental Integration Project (CO MDI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the DDCOF.

Patricia A. Braun MD, MPH, FAAP is an oral health services researcher, pediatrician at Denver Health, and professor in the School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA.

Samantha Budzyn, MPH, CHES is a Centers for Disease Control Evaluation Fellow; Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education; Catia Chavez, MPH is a senior professional research assistant; both at the Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA.

Juliana G. Barnard, MA is an instructor in the School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA.

Corresponding author: Patricia A. Braun MD, MPH, FAAP; patricia.braun@cuanschutz.edu

References

1. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral health in America: a report of the surgeon general [Internet]. Washington (DC): United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [cited 2020 March 15] Available from: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-10/hck1ocv.%40www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf.

2. Braun PA, Racich KW, Ling SB, et al. Impact of an interprofessional oral health education program on health care professional and practice behaviors: a RE-AIM analysis. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2015;6:101-9.

3. Close K, Rozier RG, Zeldin LP, Gilbert AR. Barriers to the adoption and implementation of preventive dental services in primary medical care. Pediatrics. 2010 Mar;125(3):509-17.

4. Lewis C, Lynch H, Richardson L. Fluoride varnish use in primary care: what do providers think? Pediatrics. 2005 Jan;115(1):e69-76.

5. Harnagea H, Couturier Y, Shrivastava R, et al. Barriers and facilitators in the integration of oral health into primary care: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017 Sep 25;7(9):e016078.

6. Braun PA, Widmer-Racich K, Sevick C, et al. Effectiveness on early childhood caries of an oral health promotion program for medical providers. Am J Public Health. 2017 May;107(S1):S97-S103.

7. Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Stearns SC, Quiñonez RB. Effectiveness of preventive dental treatments by physicians for young Medicaid enrollees. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar;127(3):e682-9.

8. ADHA. Dental hygiene practice act overview 2019 [Internet]. Chicago (IL): American Dental Hygienists' Association; 2020 [cited 2020 March 15]. Available from: https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/7511_Permitted_Services_Supervision_Levels_by_State.pdf.

9. Delinger J, Gadbury-Amyot CC, Mitchell TV, Williams KB. A qualitative study of extended care permit dental hygienists in Kansas. J Dent Hyg. 2014 Jun;88(3):160-72.

10. Bowen DM. Interprofessional collaborative care by dental hygienists to foster medical-dental integration. J Dent Hyg. 2016 Aug;90(4):217-20.

11. Nash DA, Mathu-Muju KR, Friedman JW. The dental therapist movement in the United States: a critique of current trends. J Public Health Dent. 2018 Mar;78(2):127-33.

12. Lenaker D. The dental health aide therapist program in Alaska: an example for the 21st Century. Am J Public Health. 2017 May;107(S1):S24-5.

13. Glenn S. The dental team concept and where the CDHC and dental therapist fit in. J Okla Dent Assoc. 2017 Jan;108(1):6-12.

14. Braun, P.A., Kahl, S., Ellison, M.C., et al. Colocation of dental hygienists. J Public Health Dent, 73: 187-194.

15. Heath B WRP, Reynolds K. A. Review and proposed standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. [internet]. Washington, (D.C): SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions; 2013 March [cited 2020 March 23] Available from: https://healtorture.org/sites/healtorture.org/files/CIHS_ICCframework.pdf.

16. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004 Feb;24(2):105-12.

17. Tolley E, Ulin, PR, Mack, N, et al. Qualitative methods in public health: a feld guide for applied research. 2nd Edition ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; c2016. Chapter 6, Qualitative data analysis: p. 175-215.

18. Miles MB, Huberman, A M, Saldaña, J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2019. Chapter 4. Fundamentals of data analysis: p. 61-99.

19. Coplen AE, Bell KP. Barriers faced by expanded practice dental hygienists in Oregon. J Dent Hyg. 2015 Apr;89(2):91-100.

20. Schlesinger AB. Behavioral health integration in large multi-group pediatric practice. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017 Mar;19(3):19.

21. Carroll AJ, Jaffe AE, Stanton K, et al. Program evaluation of an integrated behavioral health clinic in an outpatient women's health clinic: challenges and considerations. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2020 Jun;27(2):207-16.

22. Aggarwal M, Knifed E, Howell NA. A qualitative study on the barriers to learning in a primary care-behavioral health integration program in an academic hospital: the family medicine perspective. Acad Psychiatry. 2020 Feb;44(1):46-52.

23. Fong HF, Tamene M, Morley DS, et al. Perceptions of the implementation of pediatric behavioral health integration in 3 community health centers. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019 Oct;58(11-12):1201-11.