You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Alexander traced the use of silver back to ancient Persia.1 Cyrus the Great (600-530 B.C.), founder of the Achaemenid Empire (the first Persian empire), used silver vessels to keep drinking water fresh. Although the people then did not know about microbiology, they knew that water kept in silver containers did not spoil. Hippocrates (460-377 B.C.) treated ulcers and promoted wound healing using silver formulations, and the use of silver nitrate is mentioned in a 69 B.C. pharmacopeia from Rome.1 In modern times, silver nitrate has been used to prevent ophthalmia neonatorum in newborns' eyes. Today, erythromycin ointment is usually used for that purpose. Silver nitrate currently is used for treatment of common warts and for other antiseptic and antimicrobial purposes.

The authors traced the use of silver nitrate (AgNO3) for oral conditions back to 1827. Dr. D. Francis Condie (1847) reported that "Nitrate of silver was the only local remedy employed in the cases of gangrene of the mouth, that occurred in the Children's Asylum of Philadelphia, from June 1st, 1827, to January 1st, 1830, the greater portion of which terminated favourably. As soon as the disease of the mouth was detected, the nitrate of silver, either in pencil or solution, was applied, freely, to the parts affected."2 Dr. Chapin A. Harris (1850) recommended that "spongy gums that manifest no disposition to heal, their edges should be touched with a solution of the nitratum argentum (aka, silver nitrate), which will seldom fail to impart to them a healthy action."3 He also cautioned to keep the solution from "getting into the fauces, as in that case, it will cause a disagreeable nausea."3

The use of silver nitrate to chemically interfere with the course of dental caries infections dates back at least to the mid 19th century. In 1846, under the title "MISCELLANIA" in ZAHNARTZ, a German dentistry publication, a paragraph was featured with instructions for the use of "Hollenstein" (aka, hellstone, or silver nitrate) to treat dental caries lesions.4 Since 1846, there have been many other writings about silver nitrate. Prinz wrote that "Clark, Chupein, Shanasy, Tomes, Salter, Bauer, Black, Miller, Pierce, Conrad, and many others have greatly lauded the value of silver nitrate as a means of abating the progress of dental caries, and especially Taft, (Taft: Operative Dentistry, 1859, p.214)."5 Pedley's 1895 book had six references to "lunar caustic" (silver nitrate) for the treatment of tooth sensitivity and caries lesions.6 In their 1924 text, Dr. G.V. Black and his son, Dr. Arthur Black, described using silver nitrate and pictured the use the black stain that results.7 Likewise, Hogeboom,8 McBride,9 and Muhler and Hine10 in their texts described silver nitrate use for a chemical rather than mechanical approach for treating dental caries infections. Some dentists use silver nitrate for chemical treatment of dental caries to this day.

Silver diammine fluoride (SDF) (AgF[NH3]) is a liquid chemical agent made up of silver, ammonia, and fluoride that interrupts progression of dental caries infections. The solution is often referred to as silver "diamine" fluoride (with one "m"), which although chemically incorrect, has become common usage. Other terms for SDF are "silver ammonium fluoride" and "ammoniacal silver fluoride." For decades SDF has been used in other parts of the world to treat tooth sensitivity and dental caries, and it entered the dentistry marketplace in North America in 2014. As of 2019, SDF solution has been approved to treat only tooth sensitivity but has achieved wide off-label use as a chemical attenuation agent against dental caries. SDF is currently the subject of a considerable amount of dental research, continuing education lecture presentations, and published dentistry articles. Research reports, clinical case reports, technique articles with associated treatment protocols, reviews, and policy reports of university programs and professional organizations have filled contemporary scientific and commercial dental journals.11-30

Advantages in using SDF in dentistry include ease of application, no need for local anesthetic, and virtually instant and comfortable results, and it permits safe delay of more definitive treatment in patients who may not be able to tolerate or cooperate for routine restorative treatment due to age, anxiety, or financial restrictions. The biggest drawback of treatment with SDF is, as with silver nitrate treatment, the caries-infected regions of the teeth turn black. A minor disadvantage is that care must be taken when handling the SDF liquid, because it stains clothing, countertops, skin surfaces, and oral soft tissues.

Besides significant chemical interference of progression of caries infections, SDF has the ability to prevent initiation of the caries process. Horst and Heima emphasized this point in their recent erudite comprehensive review of the preventive possibilities of SDF.30 Their work included a summary of clinical trials, a comparison to other topical preventive agents, esthetics considerations, costs, SDF's effect on bonding of adhesive restorative materials, safety issues and dose limitations, application methods, reapplication frequency, tooth sites to be treated, treatment coding for third-party carriers, and billing considerations.

Commercially available soft interdental picks of various thicknesses are not only effective for clearing debris from in between contacting teeth, but their irregular side surfaces also are useful for carrying fluoride solutions into interproximal sites and agitating the fluids once inserted. This article describes and illustrates materials and methods used for saturating contacting proximal surfaces of teeth with SDF with the goal of not only attenuating dental caries lesions, but also preventing them.

Technique

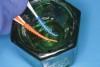

The authors' protocol for insertion of SDF-coated soft dental picks involves isolating the teeth with cotton rolls or other means, flossing the interproximal site to clear food debris and dental plaque, and then inserting a SDF-coated pick (Figure 1 and Figure 2) to saturate the contacting surfaces of the teeth with the fluid. This treatment is painless and requires no anesthetic. The pick should remain in place for at least 60 seconds and can be gently pulled in and out to agitate the fluid for enhanced surface coverage by capillary action. Additional SDF can be wiped on, using a small applicator, above the contact and in the buccal and lingual sluiceways. Excess fluid and any blood elicited may be blotted with a cotton swab. An additional 60-second insertion may be applied in the same way if there is radiographic evidence of a deeper decalcification or caries lesion. With the pick still in place, 5% (or 2.5%) fluoride varnish is painted over the treatment area, and the pick is then withdrawn.

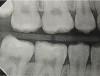

Interproximal insertion of SDF is demonstrated in different patients in Figure 3 through Figure 11. Various diameters and brands of soft dental picks may be used depending on the closeness of the proximal surfaces and ease of insertion; for example, some picks are designed for use in wider spaces between teeth. This protocol also offers versatility. Figure 3, for example, shows the simultaneous use of three thin soft dental picks to saturate proximal surfaces with SDF in a teenaged patient; the treated regions were subsequently covered with fluoride varnish (Figure 4). This patient was initially treated in April 2019 (Figure 5), with an identical re-application 3 months later. As shown in Figure 6, the December 2019 bitewing film revealed good results with the possible exception of the contact regions of the maxillary first and second molars. New SDF application was completed in the December appointment.

Figure 7 illustrates the use of thicker picks in premolar interproximal sites. Additionally, multiple picks can be used in one quadrant or in one proximal site with good isolation to maximize fluid saturation (Figure 9), which the authors have found to be an excellent time-saving strategy. Preventive or interceptive applications of SDF may also be effectively used in interproximal sites in orthodontic patients (Figure 10).

Discussion

The senior author's (TPC) private practice experience with soft-tip insertion of SDF into contacting proximal surfaces of teeth is that most beginning proximal surface caries lesions cease to progress, as evidenced by subsequent bitewing radiographic comparisons (Figure 3 through Figure 6, Figure 12 through Figure 18). The chances for success vary, however, depending on frequency of application, subsequent flossing by patients or adults flossing younger children, diet control, individual mouth chemistries, and use of fluorides for the topical effect. It must also be emphasized that office staff should make extensive efforts to inform children and parents that subsequent daily flossing is needed to accompany SDF treatments; otherwise, SDF applications will only delay the inevitable progression of caries. Flossing methods should be demonstrated for patients and for parents so they may see how to floss younger children. Showing them enlarged graphic photographs of flossing results may be helpful in this regard. Parents and patients should be made aware that if interproximal dental plaque accumulations persist without daily interruption by flossing, the acid insult will eventually take its toll on the proximal surfaces and caries lesions will progress to the point where restorative intervention may be required.

Optimal frequency of reapplication of SDF for patients logically will vary, and dentists will need to make judgments in each case. A usual protocol can be 2- or 3-month follow-up with a second SDF/fluoride varnish application after an initial treatment. Then, 6- or 12-month follow-up bitewing radiographs may be recorded to assess the status of the treated surfaces. Some dental offices do not charge additional fees within a year after a standard fee has been charged for the first application.

The authors examined the actual fluid dynamics that occur with soft-tip interproximal insertion of SDF and the suspected capillary flow that saturates a caries lesion, using an exfoliated carious primary molar and an extracted third molar (Figure 19 through Figure 25). Saturation of the caries lesion was distinct in this in vitro model. The protocol involved two 60-second applications of SDF, as well as the painting of SDF into the contact region and sluiceways.

An actual clinical result in a patient after exfoliation of the contacting primary tooth is shown in Figure 26. A year after a distal surface caries lesion on the primary second molar was attenuated with SDF, it was evident that mesial surface caries progression was intercepted and stopped on the permanent first molar.

A recent CR Foundation report on the epidemic of cervical caries in Class 2 resin box forms found that 43% of clinicians (out of 1,255 respondents) "often see caries at cervical margins" of Class 2 composites.31 That report offers an excellent evaluation of this problem and describes multiple methods of how to avoid such defects at the base of proximal sites in Class 2 restorations.

The present authors encourage research studies, perhaps done in a similar manner to the dental stone demonstration presented herein, to evaluate whether periodic interproximal soft-pick insertion of SDF to saturate proximal surfaces and gingival floor cavosurface margins may be successful to attenuate and prevent such caries infections around Class 2 restorative margins.

It may be noted that the term "arrested" is commonly used to describe the action of 38% SDF on dental caries infection. This, however, is not completely accurate. Christensen's team at TRAC Research has shown that "Recovery of a high number of viable microbes throughout SDF-treated lesions indicates significant doubt that silver diamine fluoride arrests dental caries lesion progression."32 That same report states, "Currently, there is no dental product or treatment that arrests dental caries progression; the best outcome possible today is delay of progression."32 Of course, frequency of SDF applications, home care, diet considerations, virulence of the individual's caries infection, and the patient's caries susceptibility all can influence how successful any SDF regimen might be.

Conclusion

In the senior author's practical experience in pediatric practice over 4 years, judicious use of multiple applications of SDF in primary dentitions and for permanent posterior teeth in older children and teenaged patients has shown clear and positive attenuation of the dental caries infection process. Moreover, patients, parents, and caregivers alike have been complementary of its use. In addition, because SDF intervention precludes the need for local anesthetic injections, greatly reduces behavior management concerns, and conserves clinical time, clinicians may consider it as a renewed "older style" method of approaching treatment for dental caries infections.

About the Authors

Theodore P. Croll, DDS

Adjunct Professor, Pediatric Dentistry, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (Dental School), San Antonio, Texas; Clinical Professor, Pediatric Dentistry, Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio; Clinic Director, Cavity Busters Doylestown, LLC, specializing in Pediatric Dentistry, Doylestown, Pennsylvania

Joel H. Berg, DDS, MS

Professor Emeritus, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, University of Washington School of Dentistry, Seattle, Washington

Queries to the author regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@aegiscomm.com.

References

1. Alexander JW. History of the medical use of silver. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2009;10(3):289-292.

2. Condie DF. A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Children. Philadelphia, PA: Blanchard and Lea; 1847:151.

3. Harris CA. The Principles and Practice of Dental Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lindsay & Blakiston; 1850:444.

4. Miszellen. Hollenstein bei sehr ausgehohlten Zahnen. Zahnartz. Berlin: Verlag von Albert Forstner; 1846:375.

5. Prinz P. Dental Materia Medica and Therapeutics. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 1916:217-230.

6. Pedley RD. The Diseases of Children's Teeth: Their Prevention and Treatment. London: JP Segg & Co.; 1895:189-190,196,209,219-220,231,258.

7. Black GV. A Work on Operative Dentistry in Two Volumes (Volume One), The Pathology of the Hard Tissues of the Teeth. (Treatment of decays of the deciduous incisors and canines). With revision by Arthur D. Black. 6th ed. Chicago, IL: Medico-Dental Publishing Company; 1924:247-253.

8. Hogeboom FE. Filling materials used in deciduous teeth. In: Practical Pedodontia or Juvenile Operative Dentistry and Public Health Dentistry. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 1924:60,61.

9. McBride WC. Silver nitrate precipitation. In: Juvenile Dentistry. 2nd ed. London: Henry Kimpton; 1937:192-195.

10. Muhler JC, Hine MK. Operative treatment as a method of dental caries control. In: A Symposium on Preventive Dentistry: With Specific Emphasis on Dental Caries and Periodontial Diseases. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 1956:161.

11. Nishino M. Studies on the topical application of ammoniacal silver fluoride for the arrest of dental caries [in Japanese]. Osaka Daigaku Shigaku Zasshi. 1969;14(1):1-14.

12. Yamaga R, Nishino M, Yoshida S, Yokomizo I. Diammine silver fluoride and its clinical application. J Osaka Univ Dent Sch. 1972;12:1-20.

13. Tsutsumi N. Studies on topical application of Ag(NH3)2F for the control of interproximal caries in human primary molars: 3. Clinical trial of Ag(NH3)2F on interproximal caries in human primary molars. Jpn J Pediatr Dent. 1981;19(3):537-545.

14. Chu CH, Lo EC, Lin HC. Effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride and sodium fluoride varnish in arresting dentin caries in Chinese pre-school children. J Dent Res. 2002;81(11):767-770.

15. Llodra JC, Rodriguez A, Ferrer B, et al. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for caries reduction in primary teeth and first permanent molars of schoolchildren: 36-month clinical trial. J Dent Res. 2005;84(8):721-724.

16. Braga MM, Mendes FM, De Benedetto MS, Imparato JC. Effect of silver diammine fluoride on incipient caries lesions in erupting permanent first molars: a pilot study. J Dent Child (Chic). 2009;76(1):28-33.

17. Peng JJ, Botelho MG, Matinlinna JP. Silver compounds used in dentistry for caries management: a review. J Dent. 2012;40(7):531-541.

18. Liu BY, Lo EC, Li CM. Effect of silver and fluoride ions on enamel demineralization: a quantitative study using micro-computed tomography. Aust Dent J. 2012;57(1):65-70.

19. Mattos-Silveira J, Floriano I, Ferreira FR, et al. New proposal of silver diamine fluoride use in arresting approximal caries: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:448. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-448.

20. Horst JA, Ellenikiotis H, Milgrom PM. UCSF protocol for caries arrest using silver diamine fluoride: rationale, indications and consent. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2016;44(1):16-28.

21. Mei ML, Lo EC, Chu CH. Clinical use of silver diamine fluoride in dental treatment. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2016;37(2):93-98.

22. Gao SS, Zhao IS, Hiraishi N, et al. Clinical trials of silver diamine fluoride in arresting caries among children: a systematic review. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2016;1(3):201-210.

23. Crystal YO, Niederman RN. Silver diamine fluoride treatment considerations in children's caries management. Pediatr Dent. 2106;38(7):466-471.

24. Crystal YO, Marghalani AA, Ureles SD, et al. Use of silver diamine fluoride for dental caries management in children and adolescents, including those with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39(5):135-145.

25. Chibinski AC, Wambier LM, Feltrin J, at al. Silver diamine fluoride has efficacy in controlling caries progression in primary teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2017;51(5):527-541.

26. Nguyen YHT, Ueno M, Zaitsu T, et al. Caries arresting effect of silver diamine fluoride in Vietnamese preschool children. Int J Clin Prev Dent. 2017;13(3):147-154.

27. Milgrom P, Horst JA, Ludwig S, et al. Topical silver diamine fluoride for dental caries arrest in preschool children: a randomized controlled trial and microbiological analysis of caries associated microbes and resistance gene expression. J Dent. 2018;68:72-78.

28. Horst JA. Silver fluoride as a treatment for dental caries. Adv Dent Res. 2018;29(1):135-140.

29. Zhao IS, Gao SS, Hiraishi N, et al. Mechanisms of silver diamine fluoride on arresting caries: a literature review. Int Dent J. 2018;68(2):67-76.

30. Horst JA, Heima M. Prevention of dental caries by silver diamine fluoride. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2019;40(3):158-163.

31. Clinicians Report Foundation. The epidemic of cervical caries in Class II resin box forms. Clinicians Report. 2018;11(6):1-3.

32. Clinicians Report Foundation. 38% silver diamine fluoride (SDF): does it arrest dental caries lesion progression? Clinicians Report. 2018;11(1):1-3.