You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Over 53 million people in the United States (U.S.) were identified in 2017 as residing in locations designated by the federal government as dental health professional shortage areas.1 As the U.S. continues to face disparities related to access to oral health care, one of the main contributory factors is an insufficient number of dental providers.1,2 This void is particularly apparent for underserved populations of minorities and children.1,3 Studies have shown pain and infection from untreated tooth decay is the chief complaint for dental related emergency room visits within the hospital system, leading many states to explore the incorporation of a dental therapist (DT) into the oral health workforce.4

Use of dental therapists, defined as midlevel oral healthcare providers, is being promoted as one of the ways to alleviate the nationwide access to oral care crisis and expand care to underserved populations.1,5,6 In addition to the preventive clinical skills already possessed in most states by dental hygienists (DH), the scope of practice of a DT usually includes the ability to clinically diagnose oral conditions, perform restorative procedures including filling decayed teeth and simple extractions. The dental therapy trend is spreading throughout the U.S. and approximately a dozen state legislatures are either currently contemplating proposals to incorporate some form of a midlevel provider model or have recently passed legislation for this new provider category.1 Initial reports from Alaska and Minnesota, where DT education programs have been implemented and DTs are licensed to practice, demonstrate that safe and effective care is being delivered.5,7 States including Vermont, Maine, New Mexico and Michigan have passed DT legislation and are in various stages of developing education programs. Each state has the ability to regulate the scope and level of practice to govern the adopted midlevel provider models.6,8-10

Initial perceptions among dental educators regarding the DT model have improved over time due to the observed benefits of DTs in patient care, exposure to new professionals, and information sharing among colleagues.5 Evidence of safe and effective care provided by DTs has ignited an interest in a number of states, including Oregon.5,7 The state of Oregon has been working for over twenty years to reach individuals with limited access to dental care by utilizing expanded practice dental hygienists (EPDH), a credential formerly known as the Limited Access Permit. EPDHs are RDHs who hold an expanded practice permit (EPP) to provide preventative dental hygiene services to populations with limited access to care without the supervision of a dentist. However, research by Bell et al. showed that EPDHs in Oregon may have a limited impact, due to an inability to practice to the full extent of their license.11 While a variety of settings have been approved for EPDHs to provide care, the vast majority are working with either elderly individuals or children.11 EPDHs in Oregon have identified limited knowledge regarding owning and operating a business, and difficulties in being reimbursed for services rendered as barriers to providing care.12,13 A midlevel provider, such as a DT, may be better suited to help diminish these challenges and increase access to care.

Legislation was passed in Oregon allowing for dental pilot projects for alternative providers in 2011. The language states that the project must achieve at least one of the following: teach new skills to existing categories of dental personnel, develop new categories of dental personnel, accelerate the training of existing categories of dental personnel, or teach new oral health care roles to previously untrained persons.14 As a result, two programs have been launched under the Oregon Health Authority.15,16 Workforce Pilot Project 100, approved in 2016, has an emphasis on developing a new level of dental provider and follows a model similar to the Alaska Dental Health Aide Therapist (DHAT). Short-term objectives of the pilot program are to increase the efficiency of the dental clinic and team, increase the capability of Native American tribal health programs to meet unmet needs, and the provider job and patient satisfaction. Long term goals include decreasing the rate of decay in pilot populations while increasing the treatment of decay, develop better understanding of oral health and improve oral health behaviors in the pilot communities.16

A second pilot project, "Training Dental Hygienists to Place Interim Therapeutic Restorations," focuses on teaching new skills to existing categories of dental personnel.17 The purpose of Workforce Pilot Project 200 is to demonstrate the capability of expanded practice dental hygienists (EPDH) in placing interim therapeutic restorations (ITR), restorations intended to halt the progression of dental caries until the patient is able to receive treatment by a dentist.17 The Oregon Health Authority hopes to see additional innovative pilot programs come forward.16,17

The American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) supports the expansion of the scope of practice for DHs and for the promotion of DT programs in order to provide healthcare to populations with limited access.18 Research conducted among DHs in Oregon has revealed strong support for a midlevel provider in the state and many DHs surveyed expressed a personal interest in becoming a DT.19 Furthermore, respondents also indicated that if a midlevel provider model were to be developed in Oregon, the provider should be a DH first.19 While the ADHA supports a Master's degree level education for DTs, the majority of the respondents in the Oregon study indicated that a bachelor's degree would be sufficient education.20,21 Post-graduate education can be viewed as a barrier for many associate degree educated DHs since they would have to first earn a bachelor's degree before becoming eligible to apply for a DT program at the master's degree level. It is noteworthy that the Workforce Pilot Project 100 does not require the participants to be DHs, nor does the project include the full scope of practice for the DT provider model being tested.14

With an abundance of rural communities in Oregon, along with the continued oral health need of the underserved populations, the addition of a DT midlevel provider could potentially close the care gap. While there is documented support for DTs by DHs in Oregon, the opinions of dentists remain unknown. The purpose of this study was to assess the opinions of dentists and DHs about incorporating a dental therapist (DT) into a regional dental group (RDG) located in the Pacific Northwestern states of Oregon, Washington and Idaho and the interest of the DHs employed by the RDG in becoming a DT.

Methods

This study was approved as exempt by the Pacific University, Forest Grove, Oregon Institutional Review Board. A sample population of dentists (n=220) and DHs (187) employed by a RDG in the states of Oregon, Washington and Idaho was selected for the study. Cross-sectional surveys were developed by revising a previously validated survey used with DHs in the state of Oregon.19 New questions were added to the survey and were reviewed by experts in the field to establish face validity and revisions were made. Separate surveys were created for the dentist and DH sample populations.

The 14-item survey developed for dentists contained open and closed-ended questions, including Likert-scale items. The following items were included: demographic questions, perceptions on the need for a DT, level of comfort in working with a DT, supervision and scope of practice of DT, education of a DT, proposed costs of a DT program, and compensation for DTs. Regarding the DT scope of practice question, the following description was provided: The scope of practice of a dental therapist varies, however the Commission on Dental Accreditation states that, at minimum, graduates of dental therapy programs must be able to perform pulpotomies, place crowns on primary teeth, extract primary teeth, along with preventive procedures within the scope of practice for a dental hygienist.

A 13-item survey was developed for DHs and included open and closed-ended questions, and Likert-scale items from the dentist survey. However, the DH survey included items regarding interest in becoming a DT and the desired delivery system for a DT education program.

Online survey software (Qualtrics; Provo, UT) was used to distribute the survey via the Director of Operations of the RDG, during the winter of 2017. A reminder email was sent two weeks after the original recruitment email. Participation was voluntary and respondents' identities remained anonymous.

Responses were exported into SPSS (version 24, IBM) for data analysis. The only open-ended question related to projected income levels of a DT. It was determined by two investigators to convert responses into a projected yearly salary. Hourly wage figures were converted to a weekly salary by multiplying by 40 hours and further converted to a yearly salary by multiplying by 52 weeks. In cases where a salary range was given, the middle of the range was recorded. Each of the two investigators converted the answers individually and the answers were compared manually to assess for interrater reliability. Any discrepancies were due to oversight and differing interpretation. Oversights were corrected and differing interpretation was resolved through discussion. Frequency distributions were used to describe the findings. Chi-Square tests were used to investigate possible differences between the dentist and DH respondents. An independent t-test was conducted to compare opinions of appropriate salary ranges between dentists and DHs.

Results

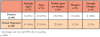

Eighty-four dentists and 187 DHs employed by a RDG in the Pacific Northwest participated in the electronic survey for response rates of 38% and 46% respectively. Collectively, 60% of the respondents practiced in Oregon (n=103), 32% in Washington (n=55) and 6% in Idaho (n=11). There were statistically significant differences between dentists' and DHs' opinions in several areas. Only 38% of the responding dentists (n=32), as compared to 65% of the DHs (n=56), believed that there was a need for a dental therapist in their community (p<0.001). DHs were more likely than dentists to believe that DTs should be an integral part of the dental team as shown in Table I (p<0.001). The vast majority of DHs (90%, n=77) as compared to a little more than half of the dentists (56%, n=48), believed that a DT should already be a DH (p<0.001). Over three-fourths of DHs (76%, n= 65) were open to having a DT in their current work setting as compared to a little more than half of the dentists (56%, n=48).

Levels of agreement of DHs regarding the DT scope of practice definition as compared to dentists are shown in Table II (p<0.001). Respondents demonstrated significant differences in perceptions regarding the appropriate level of supervision for a dental therapist, with 48% of dentists (n=39) indicating direct supervision and 57% of DHs (n=49) indicating either indirect or general supervision as shown in Table III (p<0.001). Most respondents felt that either a bachelor's degree or master's degree would be appropriate level of training for DTs provided they were already a DH (p=.160, Table IV).

Opinions regarding the level of tuition and fees appropriate for a DT educational program varied significantly between dentists and DHs; dentists indicated significantly higher tuition and fees for DT programs (p<0.001, Table V). Seventy-five percent of responding dental hygienists indicated they were very interested (n=41) or somewhat interested (n=22) in expanding their scope of practice to become a dental therapist. When asked about the most feasible avenue to obtain the necessary education to become a dental therapist, 56% (n=50) indicated an online training program with clinical internship, followed by 25% (n=22) indicating an on-site night and weekend program and 18% (n=16) indicating a traditional, on-site program.

Respondents were asked to indicate an appropriate annual salary for a DT in an open-ended question. Dentists' opinions ($78,767) varied significantly from those of DH's regarding an average annual salary ($108,434) (p<0.001).

Dentists were asked if a DT were to be employed at the RDG, whether they would be willing to supervise and oversee their work. Sixty-three percent responded yes (n=53), 19% indicated they were neutral (n=16), and 18% indicated an unwillingness (n=15). Dentists indicating an unwillingness to supervise a DT were asked to indicate what would increase their comfort level in overseeing a DT. Primary themes included appropriate training of the DT and demonstration of the DT's competency in regard to liability and supervision issues.

Discussion

Research indicates that with the future anticipated shortage of dental providers, the need for a midlevel oral healthcare provider such as the DT is growing.1,2,22 However results from this study indicate that only 38% of the dentists surveyed, as compared to 65% of the DHs, believe that a DT midlevel provider is needed as a part of the solution. Conversely, over half of the respondents in both groups agreed that a DT plays an integral part of the oral health care workforce. In addition, the majority of both dentists and DHs were open to having a DT in their current work setting. Consistent with previous studies,19 opinions of DHs indicate approval and interest in dental therapy and results from this study suggest a willingness to a strong interest from many DHs for becoming a DT.

Dentists expressed a greater concern regarding the level of supervision needed for a DT to practice and were more likely to support direct supervision as compared to DHs who supported indirect and general supervision. Dentists were also less supportive of the full scope of practice (filling decayed teeth and simple extractions) of a DT than DHs. This may be due to a lack of knowledge or appreciation towards the DHs' clinical knowledge and abilities. Studies of dentists' opinion on the professional role and expanding the practice of the dental hygienist have shown that the higher a dentist rated the importance of DHs' clinical contributions, the more often the DHs were allowed to perform diagnostic and additional procedures.21

However, a meta analysis of dentist and dental hygienists' opinions on scope of practice and independent practice of dental hygienists demonstrated no differences as a result of negative attitudes towards an expanded scope of practice for dental hygienists.21 Without corroborating studies to provide additional evidence for DT, the authors believe that this difference may be due to the DHs' desire to practice to the full extent of their license and gain more autonomy in the profession. Conversely, it is possible that dentists may have reservations because of uncertainties regarding the quality of care a DT would be capable of providing due to differences in education and experience.

Over half of dentists in this sample stated they would feel comfortable supervising a DT. Dentists may be willing to oversee a DT to ensure that the care is safe and meets the standard of care independent of other opinions regarding dental therapy. Respondents who did not feel comfortable or reported hesitation about overseeing a DT stated reasons related to liability, supervision, and training, demonstrating the need for more outcome assessment studies of currently practicing DTs.

Dentists and DHs agreed that the level of education for a DT should be either a bachelor's or master's degree; a slightly higher number of respondents believed a bachelor's degree was sufficient. Dentists' and DHs' opinions regarding the need for a master's degree more closely aligned when the potential DT was not already an RDH. The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) has developed accreditation standards for dental therapy education programs, however CODA is not prescriptive regarding the degree that should be awarded.8 Individual states will continue to make their own determination of the appropriate level of a degree for a DT.

Parallels between DTs and nurse practitioner (NP) midlevel providers can potentially be utilized to help shape the growth of DT education.23 The NP model was established to advance the education and training of a RN as a response to demands for increased cost-effective access to healthcare.23,24 Registered nurses (RNs) must achieve levels of education culminating in a Master's degree to become a NP; a similar pathway could be developed for DHs to matriculate to a DT. While NPs are able to perform limited invasive treatment procedures similar to the DT, they also focus on health promotion, disease prevention and expanding access to care.23,24

A majority of the DH respondents were interested in possibly becoming a DT. Oregon and Washington DHs are allowed to practice restorative procedures and these duties are heavily utilized within the RDG group in the study sample. While restorative permits are required for employment by the RDG, the permit is not a required for licensure in the state of Oregon. Transitioning to a DT may be viewed as an easier process by DHs who already possess a restorative permit. In terms of delivery options for the DT education program, the majority of the DH respondents stated that an online program with a clinical internship would be preferable to meeting face-to-face in the evening and weekends or a traditional onsite program. These findings concur with another survey of Oregon dental hygienists.19

Comparisons of dentists' and DHs' opinions regarding the acceptable costs of a DT educational differed significantly. Results show that DHs believe that tuition should be lower with most selecting the range from less than $10,000 to $20,000 and nearly half of dentists believing it should be higher than $41,000. The price point indicated by DHs was also similar to survey responses suggesting that the program could be delivered online, which could reduce some of the costs of face-to-face, on-site instruction. The higher tuition and fees suggested by responding dentists could potentially deter a prospective student from applying to an educational program, particularly if the potential salary is not significantly higher than that of a clinical DH.

Cost of the proposed education program is another factor that may influence interest of prospective DT students. Opinions of dentists on this topic may not be significant considering that they would not be impacted by the cost of education. However, if a DH model is developed, the opinions of DHs regarding the burden of tuition costs is worth considering by stakeholders designing DT programs or those implementing pilot programs. While the dentist respondents in this study considered higher tuition and fees to be appropriate for DT education, they also felt that the salary of a DT should be significantly lower, by approximately $30,000, than the DH respondents. Dentists' beliefs regarding DT salary levels may be attributed to their perspective of the scope of practice of a DT as compared to that of a dentist. It can be expected that a DT would earn more based on their increased level of responsibility and greater scope of practice.

Although there are currently two workforce pilot programs underway in Oregon, neither program fully encompasses the scope of practice of a DT. Based on the results of the current study, there may be adequate support from both dentists and DHs within this RDG for development of another pilot program utilizing DHs with a scope of practice paralleling that of a DT. Exactly what duties would be included in that scope of practice would need to be determined. A pilot program may be of particular interest for this RDG since two of the three states in their service area are exploring legislation for DT based midlevel providers.1

Generalization of the results from this study are limited as it was a regional survey conducted within a regional dental corporation. Opinions of dentists employed by a RDG are likely to be different as compared to self-employed, private practitioners. Additionally, dentists' opinions regarding delegating restorative functions in general may vary regionally.

Oregon and Washington have two of the most progressive practice acts for DHs which include restorative functions. National surveys would be beneficial and provide a more well-rounded understanding of the opinions of dentists and RDHs towards the midlevel DT provider model. Furthermore, outcomes assessments of the current pilot programs in Oregon can provide data demonstrating the effectiveness the alternative provider models in meeting the access to care challenges.

Conclusion

Dentists and DHs employed by a RDG in the Pacific Northwest were supportive of the concept of integrating a midlevel provider such as the DT into their practice settings. However, dentists and DHs differed significantly on a variety of aspects of the DT provider model including scope of practice and salary levels. Future studies, conducted at the national level, should survey dentists and DHs in other types of practice settings to more broadly assess acceptance and help inform the development of midlevel provider education programs.

About the Author

Yvette Ly, RDH, BSDH; Elizabeth Schuberg, RDH, BSDH; Janet Lee, RDH, BSDH; Courtney Gallaway, RDH, BSDH are graduates of the School of Dental Hygiene Studies; Kathryn Bell, RDH, MS is an associate professor in the School of Dental Hygiene Studies and Associate Dean for Inter-professional Education; Amy E. Coplen, RDH, EPDH, MS is an associate professor and Director of the School of Dental Hygiene Studies; all at Pacific University, Hillsboro, OR.

Corresponding author: Amy E. Coplen, RDH, EPDH, MS; amy.coplen@pacificu.edu

References

1. Koppelman J, Singer-Cohen R. A workforce strategy for reducing oral health disparities: dental therapists. Am J Public Health. 2017 May; 107(S1): S13-S17.

2. Blue CM, Funkhouser DE, Riggs S, et al. Utilization of nondentist providers and attitudes toward new provider models: findings from the national dental practice-based research network. J Public Health Dent. 2013 Summer;73(3):237-44.

3. Nash DA, Friedman JW, Mathu-Muju KR, et al. A review of the global literature on dental therapists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014 Feb;42(1):1-10.

4. Allareddy V, Rampa S, Lee MK, et al. Hospital-based emergency department visits involving dental conditions: profile and predictors of poor outcomes and resource utilization. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014 Apr;145(4):331-7.

5. Self KD, Lopez N, Blue CM. Dental school faculty attitudes toward dental therapy: a four-year follow-up. J Dent Educ. 2017 May;81(5);517-25.

6. American Dental Hygienists' Association. Direct access states [Internet]. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists' Association; 2016 Dec. [cited 2018 Jan 22]; Available from: https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/7513_Direct_Access_to_Care_from_DH.pdf.

7. Aksu MN, Phillips E, Shaefer HL. U.S. Dental school deans' attitudes about mid-level providers. J Dent Educ. 2013 Nov;77(11):1469-76.

8. Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental therapy education Programs [Internet]. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2015 Feb 6. [cited 2018 Jan 22]; Available from: http://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/dt.ashx.

9. American Dental Hygienists' Association. Transforming dental hygiene education and the profession for the 21st century [Internet]. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists' Association 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 29]. Available from: adha.org/adha-transformational-whitepaper.

10. Battrell A, Lynch A. Standards for dental therapy and dental hygiene education. Perpectives on the midlevel practitioner. Dimens Dent Hyg. Oct 2017;4(10):24-27.

11. Bell KP, Coplen, AE. Evaluating the impact of expanded practice dental hygienists in Oregon: an outcomes assessment. J Dent Hyg. 2015 Feb;89(1):17-25.

12. Battrell AM, Gadbury-Amyot CC, Overman, PR. A qualitative study of limited access permit dental hygienists in Oregon. J Dent Educ. 2008 Mar;72(3):329-43.

13. Coplen AE, Bell KP. Barriers faced by expanded practice dental hygienists in Oregon. J Dent Educ. 2015 Apr;89(2):91-100.

14. 76th Oregon Legislative Assembly. Senate bill 738 [Internet]. Eugene: Oregon State Legislature; 2011 Jun 1. [cited 2018 Jan 22]. Available from: https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2011R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/SB0738/B-Engrossed.

15. Indian Country Today Media Network. Oregon approves Coos Bay tribes to integrate mid-level native dental therapists [Internet]. Washington, DC: 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 22]. Available from: http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2016/02/10/oregon-approves-coos-bay-tribes-integrate-mid-level-native-dental-therapists-16337.

16. Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board. Oregon tribe's dental health aide therapist pilot project [Internet]. Portland; Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board; 2016 Jun 1 [cited 2017 Dec 19]. Available from: http://www.npaihb.org/ndti/#1508789956036-ee0a875f-a510

17. Oregon Health Authority. Dental pilot project program: training dental hygienists to place interim therapeutic restorations [Internet]. Portland: Oregon Health Authority; 2016 Mar 18 [cited 2017 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PREVENTIONWELLNESS/ORALHEALTH/DENTALPILOTPROJECTS/Pages/projects.aspx

18. American Dental Hygienists' Association. The benefits of dental hygiene-based oral health provider models [Internet]. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists' Association; 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/75112_Hygiene_Based_Workforce_Models.pdf

19. Coplen AE., Bell KP, Aamodt GL. A mid-level dental provider in Oregon: dental hygienists' perceptions. J Dent Hyg. 2017 Oct;91(5):6-14.

20. American Dental Hygienists' Association. Access to care position paper [Internet]. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists' Association; 2001 [cited 2018 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.adha.org/resources-docs/7112_Access_to_Care_Position_Paper.pdf.

21. Reinders JJ, Krijnen WP, Onclin P, et al. Attitudes among dentists and dental hygienists towards extended scope and independent practice of dental hygienists. Int Dent J. 2017 Feb;67(1):46-58.

22. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Shortage designation: health professional shortage areas & medically underserved areas/populations [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012 [cited 2018 Jan 22]. Available from: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/shortage/.

23. Taylor H. Parallels between the development of the nurse practitioner and the advancement of dental hygienist. J Dent Hyg. 2016 Feb;90(1):6-11.

24. GraduateNursingEDU.org. Nurse practitioner scope of practice [Internet]. GraduateNursingEDU.org; 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.graduatenursingedu.org/nurse-practitioner-scope-of-practice/.