You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Workplace bullying is a problem associated with occupational health and safety, negative job satisfaction and overall adverse health effects.1-12 Within healthcare, bullying is such a significant and persistent problem it is considered an occupational hazard.9-10 Workplace bullying is characterized by abusive, repetitive, health-harming mistreatment by a perpetrator that is broadly defined as persistent abusive behavior that is considered humiliating, offensive, intimidating, threatening and or demeaning to an individual or a group.8-10 Vertical bullying occurs between a boss and subordinate while lateral bullying takes place between co-workers. Consciously or unconsciously, bullies thrive on immediate power. Several types of workplace bullying have been identified, including intimidation, harassment, victimization, aggression, emotional abuse, and psychological harassment or mistreatment.13-15 Bullying behaviors offend, degrade, insult, and or threaten the target and undermine an individual's right to self-esteem or dignity in the workplace.13-15

Bullying in the workplace is a serious issue and has been reported in healthcare settings throughout the world.2-9 Portuguese researchers found that 8% of health care workers surveyed experienced bullying and in Australia almost 25% of the allied health professionals surveyed reported being a victim of workplace bullying.3,4 In the Pacific Northwest, researchers found 48% of nurses surveyed reported being victimized in the workplace, with 12% reporting being bullied at least weekly.9 Additionally, Simons studied bullying in a group of Massachusetts nurses and found a 31% prevalence rate.5 Consequently, with the increase in workplace bullying, researchers discovered that as bullying intensified, participants indicated their intention to leave the employment setting.5,6

Victims of bullying who are subjected to repeated negativity find it difficult to defend themselves against a perpetrator who engages in systematized, focused, long-term abuse. Patterns of abusive conduct associated with bullying create an ineffective work and learning environment, and targeted victims report experiencing physiological and psychological stress.7-11 Employee career satisfaction, mental health, burnout, and overall patient outcomes may be affected by bullying.11,12,15-19 Health professionals who are bullied may be more likely to make errors in judgement and treatment, which consequently affects all parties involved.18-20

Research suggests workplace bullying fosters an ineffective work environment and ongoing destruction of confidence and skills. In addition, it can cultivate negative attitudes toward a chosen job.11-15 Studies by both Lahari et al and Yildirim suggest bullying leads to low self-esteem, poor physical health and low self-confidence that can be manifested in self-doubt and a lack of work initiative and innovation.10,11 Research in the nursing profession suggests victims of bullying experience adverse occupational health outcomes that are both physiological and psychological in nature.15-18Headaches, sleep disturbances, memory problems, weight changes, substance abuse, anxiety, loss of concentration and depression were common stress related manifestations reported by those experiencing bullying.11-15 Both Spence et al and Takaki et al found that a toxic work environment created by bullying can cause nurses to experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a serious anxiety condition.16,21 Moreover, it is common for health professionals to blame themselves for being bullied, resulting in increased stress, depression, and psychological distress.18

A toxic work environment perpetuated by bullying may cause health professionals to practice less competently, leading to clinical errors and ultimately lowering the quality of patient care and negatively impacting patient outcomes.19-21 Additionally, research suggests bullying negatively affects the work performance of health care providers.19-21 Burnes and Pope found that nurses who were bullied withdrew from certain tasks, reduced their commitment to certain job responsibilities, and many decreased their amount of time in the workplace to avoid encountering the bully.22 A person bullied often feels incompetent and incapable of doing his or her job. Carter and colleagues determined that nurses experiencing workplace bullying felt their performance was impaired as they were unable to think clearly and concentrate on procedures and tasks.2 The impact of prolonged workplace bullying means that the workplace becomes dysfunctional; for the perpetrator, the bystander-patient or employee, and for the target of bullying.15

Victims of bullying have a larger propensity to be less productive, have more frequent missed work days and even leave the work force more compared to those who are not bullied.16-17 Interestingly, Simons et al discussed the bullying behaviors of more experienced nurses as "eating their young," causing newer nurses to want to quit their jobs, consequently creating an un-helpful, hostile work environment.6 As individuals terminate their positions, high staff turnover reflects poorly on the organization and places an undue burden on employers and employees as the result of hiring and orienting new staff. Interestingly, Erikson et al found that bullying increased women's long-term work-related absenteeism due to illness; however, men who were bullied just left their jobs.7 All health care professionals have the right to practice in a safe workplace, free from bullying; dental hygienists are no exception. The hierarchical nature of dentistry, gender and cultural stereotypes combined with the competitive nature of production goals may reinforce a culture of bullying in dental settings.

Few studies are available in the dental literature investigating the prevalence of bullying. In a study of 156 post graduate dental students in India, Lahari et al found that 79% of students experienced bullying although it was reported to administrators as only 34%.10 Steadman and colleagues found that out of 136 respondents, 25% of hospital dentists surveyed in the U.K. reported being victims of bullying; 60% reported experience with at least one of the identified bullying behaviors in the past year.23 Similarly, Demir at al found 24% of the 166 allied health professionals surveyed reported being bullied.24 In a multi-national study involving 655 participants from five dental schools, 10% of respondents from the American dental school surveyed reported being victims of bullying.25 Overall, results of the international study revealed 35% of all dental students surveyed reported bullying.25

Currently, there is a gap in the research related to dental hygienists and whether or not they are affected by workplace bullying. The purpose of this study was to explore the prevalence of workplace bullying in a convenience sample of Virginia (VA) dental hygienists. Information garnered from this study will help individuals and employers recognize and manage bullying behaviors in order to minimize adverse consequences.

Methods

A descriptive survey design was utilized to generate information regarding the extent to which dental hygienists in the state of Virginia (VA) perceived experiencing workplace bullying. The Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R), a valid and reliable instrument designed to measure workplace bullying, was used to survey a convenience sample of 240 VA dental hygienists attending a continuing education (CE) progam.26 The NAQ-R questionnaire determines how frequently participants experience various negative acts or behaviors that characterize bullying. The Institutional Review Board approved, online survey was available to the target population during the duration of the 3-day CE program. An introductory statement informed individuals that participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained prior to beginning of the survey. Computers were available throughout the conference, or participants could complete the survey on their personal mobile device. The instrument focused on 22 specific negative acts or behaviors with a Cronbach alpha value of .90. Three types of bullying were measured with the NAQ-R: work related, personal and physical intimidation. In order to avoid possible response bias, the term "bullying" was not used at the beginning of the survey or in any of the survey questions. Participants indicated how often they experienced each negative behavior or act (never, now and then, or monthly, weekly or daily) in the workplace within the past six months. According to Einarson et al, experiencing at least two negative behaviors at least weekly over the past six months indicates bullying.26 In addition to the NAQ-R, participants responded to six demographic questions (age, gender, education, ethnicity, employment and position), a question on recent workplace bullying, and if their current employment setting had written policies on bullying. Data was collected with Qualtrics statistical program (Provo, Utah). The survey program was set with the option "Prevent Ballot Box Stuffing," so respondents could respond only one time to the survey.

Results

Of the 240 VA hygienists invited to participate, 153 completed the survey in its entirety (n=153) for a response rate of 64%. Data revealed that 42% of the participants were employed in a solo dental practice, followed by 39% in a group practice. The vast majority of participants were female (97%) and white (84%). Approximately two thirds, 62%, had obtained a baccalaureate degree and 26% an associate's degree. Just over one half (53%) of the respondents were under the age of 50 and 10% over the age of 60 (Table I). The prevalence of negative behaviors experienced by all participants in each of the three categories (work-related, physical intimidation, personal) are shown in Table II. Within the three categories (work-related, physical and personal), experiences of work-related bullying were the most common, followed by personal and physical intimidation (Table II).

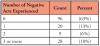

Results suggest that approximately 24% of the participants experienced work related bullying weekly or daily in the past 6 months as defined by the NAQ-R. Of these, 18% reported experiencing three or more negative acts at least weekly (Table III). Results of the negative act survey responses from all candidates, as compared to the 24% of respondents who met the criteria for bullying are shown in Table IV. The most frequent negative behaviors experienced on a weekly or daily basis by those who met the criteria for bullying were: opinions and views ignored (73%), experiencing unmanageable workloads (68%) and having one's work excessively monitored (68%) (Table IV).

At the end of the survey a definition of bullying was provided, and all participants were asked the question, "are you experiencing workplace bullying?" to which 14% indicated yes. However, based on the criteria for bullying (2 or more negative acts), 24% of respondents actually experienced workplace bullying as defined. These results suggest some participants were being bullied but were unaware.

One-half of all respondents reported no workplace bullying policy existed in their place of employment and 25% of the respondents stated they were unsure if a policy existed. Of the 24% of respondents who met the criteria for being bullied, slightly less than a third, 32%, reported that their employment setting had a bullying policy, 54% reported no policy existed, and 14% reported they did not know if a policy existed in their employment setting.

Discussion

Workplace bullying has become a serious and escalating problem that negatively affects a significant proportion of healthcare professionals. As a result of its negative consequences on the overall health and well-being of employees, the importance of understanding its prevalence, as well as factors that contribute to the emergence of bullying is critical. Study results show that nearly one-quarter (24%) of the respondents reported experiencing workplace bullying over the past 6 months. These findings are similar to other studies in health care, with rates ranging from 20% to 27%.2,24,27 Results suggest nearly one in four participants in the present study experienced bullying, but only one in seven recognized that workplace bullying was occurring. In order to address workplace bullying, dental hygienists must first identify if bullying exists, then develop proactive action plans to counter negative acts of bullying. A significant number of participants were not aware they were bullied, suggesting that awareness, education and policies are needed. The psychological and physical stressors associated with bullying can take a negative toll on victims, leading to dissatisfied employees who may be prone to make patient care mistakes, call in sick, as well as leave the work setting and even the profession.28 Therefore, the dental hygiene profession should advocate for bullying education and policies that promote zero tolerance in the workplace.

As a profession of predominately women, dental hygienists may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of workplace bullying. The most likely victims of workplace bullying are frequently women associated with differing positions of power held between men and women. Notably, in 2014, the Workplace Bullying Institute polled a national sample of 1,000 adults, demonstrating that 62% of the bullies were men and 58% of the targets were women.29 Another study in a medical school setting reported that 50% of participants had been bullied and of these, 70% were women.30 Moreover, Townsend et al found young women who experienced bullying were more likely than men to use tobacco or illicit drugs, be obese and be at risk of poor physical health, psychological distress, suicidal thoughts and self-harm.31

Leymann identified four factors contributing to workplace bullying: low morale, deficiencies in work design, poor behavior of leaders and socially exposed position of the target.32 Individuals in positions of power who are cognizant of these factors may be more adept at preventing and managing workplace bullying. Dental personnel need to be educated in how to identify bullying, manage conflict and handle grievances. Bullies are toxic to the work environment and hold the team back from achieving goals and positive outcomes. An employee creating an unhealthy work environment, no matter how great their clinical expertise, is detrimental to the practice. Education to ensure identification and management of bullying may promote greater self-advocacy and a healthier work environment for dental professionals. Professional associations could offer seminars or CE related to the topic. Furthermore, dental hygiene students could benefit from the addition of curriculum on bullying in practice management courses.

Dental professionals should learn to eliminate bullying from their own behavior and promote a culture of safety and respect. In the present study, the majority of dental hygienists who indicated bullying occurring at their place of employment were over the age of 40. It is possible that older participants are more aware and better able to identify and manage bullying behaviors through increased life and work experiences; however, these results could also indicate that younger employees may be more likely to bully older employees. Since the researchers relied on respondents' self-reporting, individuals may have been hesitant to express their true opinions. Results of the present study differ from those of Simons et al, which found increased bullying affecting younger, newly graduated nurses.6 Effective role modeling will help minimize negative behaviors and acts, foster better individual health, as well as promote a positive work culture.23

Most respondents were not aware if their employment setting had a workplace bullying policy or stated none existed. A well thought-out, written bullying policy plays an important role in fostering a collaborative, healthy workplace and should be communicated to all employees. Policies should outline steps to prevent bullying, protect staff that report bullying and/or cooperate in investigations, and have clear consequences and repercussions for perpetrators. Additionally, policies should be visible, reviewed, and regularly updated by all employees. Without written policies, dental hygienists may be fearful of retaliation if they report workplace bullying. Polices must be implemented and enforced, otherwise victims may not feel comfortable reporting incidents of bullying.33 Dental professionals can employ questionnaires such as the NAQ-R when developing polices and prevention plans to provide an ongoing analysis of negative behaviors and work to proactively target the most frequently reported negative behaviors. Most importantly, the root cause of bullying should be identified and steps put in place to remedy this behavior.20 All members of the dental team need to be treated with respect and focus on collaboration and teamwork, which ultimately promotes higher quality patient care. A clearer understanding of the manifestation of bullying can lead to a reduction or elimination of negative workplace behaviors.

Study Limitations

Intrinsic methodological limitations of this study should be recognized. The incidences of bullying were measured through self-report, which might have impacted findings, causing one to assume a corresponding bias in the key variables. There is a risk of over or under estimating the prevalence of bullying as reported by a convenience sample of dental hygienists in the same geographic location. Future research should focus on identifying the specific perpetrator of the bullying and identify whether it is vertical or horizontal bullying, in addition to the role of patients in workplace bullying. The survey was only available for a 3-day period, which may have affected response rate. Study replication with a national sample of dental hygienists is warranted to determine which factors in dental practice settings contribute to workplace bullying. Results should be assessed cautiously as they represent only the viewpoint of the victim of the bullying, not the perpetrator. This partial perspective of this phenomenon should be considered in future research.

Conclusion

Approximately 24% of the study participants experienced workplace bullying on a daily or weekly basis. The most common negative behaviors revealed were having their views and opinions ignored, receiving unmanageable workloads, and having their work excessively monitored. Over half of the respondents meeting the criteria for bullying reported that their employment setting had no bullying policy and 14% did not know if a policy existed. Study findings support the need for additional research on the prevalence and impact of workplace bullying, as well as the need to develop effective strategies and policies to eliminate these behaviors. Workplace bullying can take many forms and is a problem that can have detrimental effects on the overall well-being of those targeted by this behavior and the culture of the organization. Proactive strategies through intra and inter-collaborations with dental and other health professionals could help effectively address the broader issue of workplace bullying.

About the Authors

Gayle B. McCombs, RDH, MS, is an emeritus faculty professor; S. Lynn Tolle, RDH, MS is a university professor; Tara L. Newcomb, RDH, MS is an associate professor and director of clinical affairs; Ann M. Bruhn, RDH, MS is an associate professor and interim program chair; Amber W. Hunt, RDH, MS is a visiting lecturer; all at the School of Dental Hygiene, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA

Lanah K. Stafford, MA is a senior research associate, Office of Institutional Effectiveness and Assessment, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA.

Corresponding Author: Gayle McCombs, RDH, MS; gmccombs@odu.edu

References

1. Giorgi G, Mancuso S, Fiz PF, et al. Bullying among nurses and its relationship with burnout and organizational climate. Int J Nurs Pract. 2016 Apr;22(2):160-8.

2. Carter M, Thompson N, Crampton P, et al. Workplace bullying in the UK NHS: a questionnaire and interview study on prevalence, impact and barriers to reporting. BMJ Open. 2013 Jun; 3(6): e002628.

3. Norton P, Costa V, Teixeira J, et al. Prevalence and determinants of bullying among health care workers in Portugal. Workplace Health Saf. 2017 May;65(5):188- 96.

4. Askew DA, Schluter PJ, Dick ML, et al. Bullying in the Australian medical workforce: cross-sectional data from an Australian e-Cohort study. Aust Health Rev. 2012 May;36(2):197-204.

5. Simons S. Workplace bullying experienced by Massachusetts registered nurses and the relationship to intention to leave the organization. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2008 Apr-Jun;31(2):48-59.

6. Simons SR, Mawn B. Bullying in the workplace--a qualitative study of newly licensed registered nurses. AAOHN J. 2010 Jul;58(7):305-11.

7. Erikson T, Hogh A, Hansen A. Long-term consequences of workplace bullying on sickness absence. Lab. Econ. 2016 Dec; 43:129-150.

8. D'Cruz P, Paull M, Omari M, et al. Target experiences of workplace bullying: insights from Australia, India and Turkey. Empl. Rel. 2016 Aug 1;38(5):805-23.

9. Etienne E. Exploring workplace bullying in nursing. Workplace Health Saf. 2014 Jan;62(1): 6-11.

10. Lahari A, Fareed N, Sufhir K. Bullying perceptions among post graduate dental students of Andra Pradesh India. J of Ed and Ethics in Dent. 2012 Jan-Jun;2(1):20-24.

11. Yildirim D. Bullying among nurses and its effects. Int Nurs Rev. 2009 Dec;56(4):504-11.

12. Khubchandani J, Price JH. Workplace harassment and morbidity among US adults: results from the national health interview survey. J Community Health. 2015 Jun;40(3):555-63.

13. Aquino K, Lamertz K. A relational model of workplace victimization: social roles and patterns of victimization in dyadic relationships. J Appl Psychol. 2004 Dec;89(6):1023-34.

14. Birks M, Cant RP, Budden LM, et al. Uncovering degrees of workplace bullying: a comparison of baccalaureate nursing students' experiences during clinical placement in Australia and the UK. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017 Jul; 25:14-21.

15. Cleary M, Hunt GE, Horsfall J. Identifying and addressing bullying in nursing. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010 May;31(5):331-5

16. Takaki J, Taniguchi T, Fukuoka E, et al. Workplace bullying could play important roles in the relationship between job strain and symptoms of depression and sleep disturbance. J Occup Health 2010 Jan;52: 367-74.

17. Reknes I, Pallesen S, Magerøy N, et al. Exposure to bullying behaviors as a predictor of mental health problems among Norwegian nurses: results from the prospective SUSSH-survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014 Mar;51(3):479-87.

18. Houck NM, Colbert AM. Patient safety and workplace bullying: An integrative review. J Nurs Care Qual. 2017 Apr-Jun;32(2):164-71.

19. Laschinger HK. Impact of workplace mistreatment on patient safety risk and nurse-assessed patient outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2014 May;44(5):284-90.

20. Wallace CS, Gipson K, Wallace CS. Bullying in healthcare: a disruptive force linked to compromised patient safety. Pa Pat Saf Advis. 2017 Jun;14(2):64-70.

21. Spence HK, Nosko A. Exposure to workplace bullying and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology: the role of protective psychological resources. J Nurs Manag. 2015 Mar;23(2):252-62.

22. Burnes B and Pope R. Looking beyond bullying to assess the impact of negative behaviours on healthcare staff. Nurs Times. 2009 Oct;105(39):20-4.

23. Steadman L, Quine L, Jack K, et al. Experience of workplace bullying behaviours in postgraduate hospital dentists: questionnaire survey. Br Dent J. 2009 Oct;207(8):379-80

24. Demir D, Rodwell J, Flower R. Workplace bullying among allied health professionals: prevalence, causes and consequences. Asia Pacific J of HR. 2013 Oct;51(4):392-405.

25. Rowland ML, Naidoo S, AbdulKadir R, et al. Perceptions of intimidation and bullying in dental schools: a multi-national study. Int Dent J. 2010 Apr;60(2):106-12.

26. Einarsen S, Hoel H, Notelaers G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the negative acts questionnaire-revised. Work & Stress. 2009 Jan 1;23(1):24-44.

27. Johnson SL, Rea RE. Workplace bullying: concerns for nurse leaders. J Nurs Adm. 2009 Feb;39(2):84-90.

28. Wilson JL. An exploration of bullying behaviours in nursing: a review of the literature. Br J Nurs. 2016 Mar- Apr;25(6):303-6.

29. 2014 WBI U.S. Workplace bullying survey [Internet]. Clarkston: Workplace Bullying Institute; 2018 [cited 2018 Jan 23]. Available from: http://workplacebullying.org/multi/pdf/WBI-2014-US-Survey.

30. Mukhtar F, Daud S, Manzoor I, et al. Bullying of medical students. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010 Dec;20(12):814-8.

31. Townsend N, Powers J, Loxton D. Bullying among 18 to 23-year-old women in 2013. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017 Aug;41(4):394-98.

32. Leymann H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 1996 Jun 1;5(2):165-84.

33. Murray JS. Workplace bullying in nursing: a problem that can't be ignored. Medsurg Nurs. 2009 Sep-Oct;18(5):273-76.