You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Patients with sleep-related breathing disorders may have a simple diagnosis such as snoring or more complicated challenges such as upper airway resistance syndrome. or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which can result in excessive daytime sleepiness, drowsiness, impaired neurocognitive function, and potentially higher risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality.1,2 OSA, which is somewhat common, occurs when the muscles in the back of the throat relax excessively, causing the airway to narrow and completely close due to a lack of support for the soft palate, uvula, tonsils, and tongue.3 Risk factors for sleep-related breathing disorders include obesity, narrow airway, hypertension, chronic nasal congestion, smoking, diabetes, and a family history of sleep apnea.3

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Lifestyle Changes

Several options are available for patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, exercise, reducing alcohol consumption, and quitting smoking, may help reduce symptoms, but many patients need more advanced therapy to help with these disorders.3 Certain devices worn during sleep can help patients open their airways.

Sleep Devices

The most common type of sleep device is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), a machine that delivers air pressure through a mask that fits in or over the patient's nose and mouth, which helps keep the airway open.3 Although CPAP is an effective treatment, the challenges of this therapy include low acceptance and patient adherence; some patients find the mask or machine uncomfortable or noisy.2,3

Oral appliance therapy with a custom-fit device is an alternative treatment option for these disorders.2 With oral appliance therapy, the mandible is held in a forward position, which keeps the airway open and prevents collapse.2 Similar to a mouthpiece worn as a sports mouthguard or retainer, the appliance fits in the mouth and supports the jaw position.4 Oral appliances may be more comfortable than CPAP devices and are small, quiet, and portable, although they may have adverse effects such as mouth or teeth discomfort, orthodontic changes, and excessive salivation.4,5

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine's previous guidelines noted that oral appliances should be used as first-line therapy for patients with mild to moderate OSA or those patients for whom CPAP is not successful in more severe cases of OSA.6 However, newer guidelines indicate that oral appliance therapy should be considered in all cases of CPAP-intolerant adult OSA patients or those patients who prefer an alternative treatment option as opposed to no therapy at all.7To properly fabricate a custom oral appliance, it is imperative to obtain dental impressions or intraoral digital scans of the patient's dentition and bite registration.

BITE REGISTRATION

Bite registration is an important factor in oral appliance fabrication. If the patient is not set in a position that will open the airway when the bite registration is completed, the device is unlikely to be successful. A few tools may be used to create the bite registration, such as the Airway Metrics system and the George Gauge. These tools allow clinicians to find the optimal position at the beginning of treatment.

The George Gauge technique measures the patient's maximum protrusion and uses that measurement to calculate where to set the patient in the given position to open the airway. For example, if a patient has a 10-mm range of motion and the objective is to set them at 60% to 70%, the patient would be set at a 6-mm or 7-mm anterior-posterior position.8

The Airway Metrics system consists of a snore screener and 15 mandibular positioning simulators (MPS) in a cassette, along with nine vertical titration keys.9 The snore screener pro-vides an estimate of how the position affects the airway. It is then fine-tuned with the MPS by asking the patient to make a snore sound at different protrusive and vertical positions while laying supine. This helps determine the optimum airway and comfortable treatment position for the patient. A bite fork and handle are then used to obtain a bite registration at the desired anterior/vertical starting position. The titration keys enable vertical shimming after the initial anterior/vertical position is obtained. This technique engages the patient in treatment to help determine the correct bite for the oral appliance.

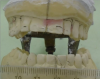

Regardless of the combination of tools used to obtain the bite registration, when the material is setting, the patient may tend to move because it is not a natural position for him or her, which may result in midline shifts (Figure 1 and Figure 2). After the bite registration is taken, the excess material should be trimmed before putting it back into the patient's mouth. The midlines should be checked again, with the patient sitting for several minutes to make sure he or she is comfortable in that position. There are many moving parts, so this helps give the patient and doctor an idea of how comfortable they are with this measurement.

Another factor to remember is the Curve of Spee, which will often dictate the vertical dimension. When the Curve of Spee is high, the distal of the last molar of the lower arch will determine the height of the device. Placing occlusal rests or finger rests on the mesial of the last molar allows the clinician to keep the vertical in the desired position. Otherwise, the vertical may need to be increased to cover the distal of the last molar (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

When taking a bite registration, providing more occlusal detail will help the laboratory develop the oral appliance without guesswork. Lack of occlusal detail makes it difficult to position the models well, which leaves too many variables for the technicians. Greater detail of all occlusal surfaces inform the technician exactly where the arches need to be set.

There is also the digital process, which still requires a similar bite registration. After the bite has been taken, the posterior quadrants are cut away until the clinician is left with just the anterior portion of the bite. When this is in the patient's mouth, it allows the posterior area to be scanned with the software to map the bite, essentially showing the sleep bite within the digital scan.

IMPRESSION MATERIAL: POLYVINYL SILOXANE (PVS) VS ALGINATE

Taking impressions of the patient's dentition after the final position is determined involves the impression material of one's choosing. It is possible to get good impressions with both alginate and PVS (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The challenge with alginate is the distance in shipping to the laboratory. If models are poured in the dental office, they can be damaged during shipment, and the laboratory cannot do anything until the patient is back in the office for new impressions, which will delay the process. It is also possible that alginate will yield some distortions, chips, and air pockets. PVS is another option that offers good detail for impressions. Sleep devices cover every surface of the tooth, so good definition is important when taking an impression. The gingival margins aid the laboratory technicians in surveying the undercuts to fabricate a properly fitted device.

ORAL APPLIANCE FABRICATION OPTIONS

Hard vs Hard/Soft Fitting Surfaces

Oral appliances are offered in both hard and hard/soft fitting surfaces. The benefit of the hard-fitting surface is that it can be adjusted easily. If the patient has a filling or restoration, one can grind the material easily and realign it if necessary. It also has ball clasps for retention to tighten it if it ever becomes loose. Essentially, the hard material has the advantages of easy adjustment and longevity. The soft material may be more suitable for patients with veneers, or when more retention is needed with short clinical crowns for which better suction is needed against the teeth. The challenge of soft material is that it is porous and can absorb moisture.

Modifications

Oral appliances can be modified to the needs of each patient. Various options, such as adding retrusive ability into the device, ball clasps, reduced lingual material, occlusal or finger rests, anterior bumps, and elastic hooks, can be used in some combination to increase comfort and effectiveness.

It is possible to add retrusive ability into the oral appliance if it is felt that the position is going to be successful, but he or she is uncomfortable because the lower jaw is protruded too far. The device can be brought back from the starting position by 1 or 2 mm, which is useful in patients with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) concerns. Note: this should be indicated on the laboratory sheet if needed because it does not come as standard.

Ball clasps are used as auxiliary retention in conjunction with tooth undercuts. Reduced lingual is another common option, where the lingual material is cut away to create more space in the oral cavity. This may help patients with a larger tongue or sensitive gag reflex. However, it is important not to choose the reduced lingual option if the patient has small undercuts.

For those patients with a larger tongue or sensitive gag reflex, occlusal or finger rests are another good alternative. They are also recommended for those patients with a high Curve of Spee. With this selection, the material does not go all the way back, so it does not encroach on tongue space.

Anterior bumps are often used in patients with TMJ disfunction. This alternative takes the pressure off the posterior so that the patient is only contacting in the anterior. Another option is to add elastic hooks that are designed to guide the patient back to a closed position to create lip seal, an important factor when trying to encourage nasal breathing. They do not hold the patient in a locked position, but they may be suitable for a patient who sleeps on his or her back or with an open mouth to help guide the lower jaw back to a closed position.

Product Options

Several companies offer a variety of oral appliances, including the SomnoDent® sleep apnea oral appliance (SomnoMed, somnomed.com); Respire Blue, Blue EF, Pink, Pink EF, and Pink EF Micro (Whole You™, wholeyou.com); and the O2Vent™ (Oventus, oventusmedical.com). These devices can all be modified according to the individual patient to offer the best possible position for sleep and comfort.

Summary

Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to their patients with sleep-related breathing disorders because severe OSA and related conditions are potentially dangerous. For the clinician to be most effective, it is important to understand the treatment options and modifications of available devices. Accurate and detailed bite registration along with determining the perfect jaw position using various tools are imperative initial steps in successful treatment.

References

1. Doff MH, Finnema KJ, Hoekema A, et al. Long-term oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea syn-drome: a controlled study on dental side effects. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(2):475-482.

2. Tsuda H, Wada N, Ando S. Practical considerations for effective oral appliance use in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a clinical review. Sleep Science and Practice. 2017;1:12. doi: 10.1186/s41606-017-0013-8.

3. Mayo Clinic. Obstructive sleep apnea. https://www. mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/obstructive-sleep-apnea/symptoms-causes/syc-20352090. Accessed August 31, 2018.

4. American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. Oral appliance therapy. https://www.aadsm.org/oral_appli-ance_therapy.php#. Accessed August 31, 2018.

5. American Dental Association. Evidence brief: oral appliances for sleep-related breathing disorders. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/ADA_SCI_OralAppl_SRBD_Brief_Final_15.pdf?la=en. Accessed August 31, 2018.

6. Kushida CA, Morgenthaler TI, Littner MR, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances: an update for 2005.Sleep. 2006;29(2):240-243.

7. Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring with oral appliance therapy: an update for 2015. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(7):773-827.

8. Space Maintainers Laboratories. The George Gauge. https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/b1b2ce0c/files/uploaded/George%20Gauge%20Instructions%20%282%29.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed September 25, 2018.

9. Welcome to Airway Metrics. http://www.airwaymet-rics.com/index.html. Accessed September 13, 2018.