You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Today, more than ever, consumers are being bombarded via social media, the Internet, and traditional media outlets regarding quick and inexpensive methods for smile enhancement through tooth whitening. A recent search on YouTube for "teeth whitening" resulted in over 662,000 videos, with most focused on at-home tooth whitening remedies that included everything from oil pulling to use of activated charcoal. This comes as no surprise, considering a survey conducted by the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry that confirmed the desire for whiter, brighter teeth and belief that a smile is an important social asset.1

The significance of societal aspects in relation to oral health has been acknowledged through definitions of oral health from the American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) in 1999 and by the FDI World Dental Federation in 2016. ADHA defines optimal oral health as a standard of health of the oral and related tissues that enables an individual to eat, speak, and socialize without active disease, discomfort, or embarrassment, and which contributes to general well-being and overall health.2

FDI defines oral health as follows: Oral health is multi-faceted and includes the ability to speak, smile, smell, taste, touch, chew, swallow, and convey a range of emotions through facial expressions with confidence and without pain, discomfort, and disease of the craniofacial complex.3 Clearly the interest in whitening exists, and it is important that the dental hygienist be involved in this process to assure long-term success and optimal oral health.4 Surveys have also confirmed that patients who undergo esthetic procedures such as whitening may be more inclined to maintain that result, thereby improving their daily oral care routines.5

The Role of the Dental Hygienist

The Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice define the role and practice responsibilities of the dental hygienist.6 Dental hygienists are viewed as experts in their field; are consulted about appropriate dental hygiene interventions; are expected to make clinical dental hygiene decisions; and are expected to plan, implement, and evaluate the dental hygiene component of the overall care plan.

The Standards can be downloaded at: https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf and should be a part of every dental hygienist's resources. Whitening, while certainly cosmetic, plays a significant role in oral health and self-esteem. As such, patient education on the plethora of whitening options should be included as well as an assessment of whitening candidacy for every patient.4 In an ADHA Access Standards column, professional whitening was the focus7; this article reviews the whitening process and how the Standards for Clinical Practice are applied and met. The overview provides key information on the best practices and clinical strategies for successful professionally supervised whitening and can be downloaded at: http://adha.org/resources under the ADHA Standards in Clinical Practice Column tab, in the Resources section of the website.

The opportunity to deter clients from selecting over-the-counter and Internet-touted products or at-home remedies that do not whiten and may even harm dentition and soft tissue can be managed in the dental hygiene appointment. Further, professionally supervised whitening is recommended by the American Dental Association (ADA) to assure clients are appropriately evaluated and treatment-planned according to dental health, individual needs, and use of effective tooth whitening systems.8,9

Top Trends in Tooth Whitening

A consumer survey regarding whitening practices reported a disturbing trend of patients self-diagnosing and selecting over-the-counter products to whiten their teeth. The survey, conducted by Mintel, showed that 41% of respondents have tried to whiten their teeth using toothpaste, 17% used mouthwash, and 15% tried over-the-counter whitening strips. Only 10% were using professional whitening.10 This has been compounded via the Internet, social media, and traditional media outlets. The ADA consumer web site www.MouthHealthy.org features an overview of natural tooth whitening remedies, which include use of fruits, scrubs, and spices/oils.11

The use of lemons/apple cider combined with baking soda is hyped as a natural whitener with no evidence to support the claims, and it may even harm enamel. One of the biggest trends has been the use of activated charcoal (scrubs), where capsules or specifically designed oral pastes, creams, and powders are applied via a toothbrush. A recently published review of literature showed insufficient clinical and laboratory data to substantiate the safety and efficacy claims of charcoal and charcoal-based dentifrices.12 Neither whitening via oil pulling, in which users "swish" with coconut oil (which starts out as a solid) for up to 20 minutes daily, nor the use of turmeric is supported by scientific evidence.

Clients who use these methods or ask questions about them, or the numerous other at-home remedies featured online, demonstrates an interest in smile enhancement and an opportunity for clinicians to educate and redirect accordingly. Professionally supervised whitening continues to be the most well-researched and effective means for tooth whitening.

Trends in Professionally Supervised Whitening

Professionally supervised whitening can be separated into two distinct categories: chairside/in-office-administered whitening and professionally dispensed/recommended whitening. Carbamide and hydrogen peroxide are used in varying concentrations and have been proven effective and safe.13 When peroxide-based agents come into contact with tooth surfaces, they break down and remove or dissolve stain molecules within both the dentin and enamel surfaces through oxidation. Both external and internal stains deep in the tooth structure are impacted. As this process continues, the enamel surface becomes more opaque and reflects light, making the teeth appear whiter and brighter.14 A regimen consisting of in-office whitening for two sessions with a 1-week interval, followed by home whitening once a month for 3 months, gave more persistence in color change over a 6-month period than in-office bleaching alone.15

Sensitivity has been the leading reported side-effect of professional whitening products, which has been addressed through the addition of desensitizing agents such as sodium fluoride, amorphous calcium phosphate, and potassium nitrate. With the plethora of professionally administered and dispensed options available today, an important resource for the clinician continues to be manufacturers of whitening technologies and published research. It is important to note that peroxide-containing options are available direct to consumers on the Internet, social media, and traditional media outlets. As such, clinicians should be familiar with these options or at minimum be prepared to research these products for efficacy and safety. Additionally, there are numerous products available over-the-counter that claim to whiten that do not contain peroxide that will either reduce stain adherence or minimize extrinsic staining. Other considerations include gingival irritation as a side effect16 and that whitening may be contraindicated for children, pregnant women, and patients with anterior restorations and caries.8,17-19

Trends in Whitening Maintenance

After ideal tooth color has been achieved, numerous options are available to maintain whitening results. App-connected power toothbrushes with "whitening" modes; various peroxide-containing and non-peroxide-containing strips, pastes, gels, and rinses; and a recently introduced water irrigation whitening system can assist clients in maintaining results and minimizing extrinsic stain accumulation. It is important for clinicians to respond to clients' needs with up-to-date information and education with respect to selecting strategies that are effective and safe.

As the desire for whitening continues to grow, it has become important for clinicians to incorporate whitening knowledge to provide clients with the latest in trends and technologies. An understanding that social factors greatly influence oral health has paved the way for dental hygienists and their role in education and facilitation of tooth whitening. Professionally supervised whitening is the best method to achieve optimal results and may even impact overall oral health.

Updates on Air Polishing

Dental hygienists understand that stain removal is important because patients want cleaner, brighter smiles. Clinicians balance appointment time to provide therapeutic subgingival debridement while also meeting esthetic goals by removing supragingival deposits and tooth stain. Although polishing is often considered cosmetic, it is time to think of air polishing as both an esthetic and therapeutic procedure with the use of subgingival powders such as glycine.

Although hand or power-driven instruments are necessary to remove calculus deposits, subgingival air-polishing applications can effectively remove biofilm and contribute to the periodontal health of patients.20-22 Supragingival air polishing directed into the periodontal pocket with glycine powder removes biofilm subgingivally up to 4 mm, and research shows that subgingival air polishing removes biofilm and reduces periodontal pathogens greater than or equal to 5 mm in periodontal pockets better than curettes and in less time than debridement with hand or power-driven instruments.23

Potential Periodontal Benefits

Evidence of potential periodontal health advantages is based primarily on the use of subgingival air polishing in periodontal maintenance. Findings for air polishing with glycine powder indicate:

• Supragingival air polishing reduced gingival inflammation and plaque index scores.24

• Supragingival air polishing with glycine powder resulted in significantly less gingival abrasion and damage to dentin and cementum than air polishing with sodium bicarbonate powder.24,25

• Supragingival air polishing is as effective as curettes or ultrasonic instruments in removing biofilm subgingivally in 3 to 4 mm probing depths.26

• Full-mouth air polishing significantly reduces Porphyromonas gingivalis and F. nucleatum counts associated with periodontal disease.20,22

• Evidence supports use of subgingival air polishing with a low abrasive powder and a subgingival nozzle in moderate periodontal pockets (greater than or equal to 5 mm) to remove periodontal pathogens equally as well as hand instruments.20,23

• Studies have shown, in probing depths greater than or equal to 5 mm, air polishing using a subgingival nozzle is more effective in subgingival biofilm removal than manual or ultrasonic instruments.22,23

• For peri-implant mucositis, air polishing or an ultrasonic device is effective in reducing plaque scores, bleeding on probing, and number of pockets greater than or equal to 4 mm compared with baseline.27

• No adverse effects have been shown when using glycine powder air polishing for nonsurgical treatment of peri-implant diseases.28,29

Patient Preference

Although debridement with ultrasonic or hand instruments is effective in reducing inflammation and bleeding on probing in periodontal maintenance therapy,20 it is time-consuming, and patients can perceive it as uncomfortable. Full-mouth supra- and subgingival air polishing removes biofilm and light stain, saving time during maintenance appointments.24 Patients often report a salty taste when sodium bicarbonate powder is used. Use of a glycine powder supra- or subgingivally addresses this concern, especially in patients without significant or heavy stain, because it does not have an objectionable taste. Glycine powder used for supra- and subgingival air polishing is odorless, low-abrasive, and water-soluble, and patients find it more comfortable than other modalities used in nonsurgical periodontal therapy30 as well as more acceptable compared with ultrasonic instrumentation.22 One recent study showed that glycine air polishing could save half the treatment time and double the patient's comfort compared with power scaling and rubber-cup polishing.31

Choosing an Air Polishing Device and Powder

For safe and effective air polishing, the dental hygienist must choose the appropriate powder. Powders indicated for supragingival use, such as the commonly used sodium bicarbonate or calcium carbonate powders (or aluminum trihydroxide for sodium intolerant patients), have particle shapes or hardness that make them effective at stain removal but too abrasive for subgingival use. Subgingival powders, such as glycine and erythritol powders, are the least abrasive on cementum, implants, and dental materials. While these powders are also appropriate for supragingival biofilm removal, they may require additional time for moderate to heavy stain removal. Currently, glycine powder is the only subgingival powder available for use in the United States. Glycine has the following advantages30:

• Indicated for supragingival and subgingival use

• Safe for use on the gingiva and mucosa

• Safe for use on implants

• Safe for orthodontic brackets

• Perceived to be more comfortable than other powders30,31

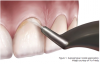

Glycine powder can be used in most commercially available air-polishing devices. Low-abrasive glycine powder is time-efficient and recommended both supra- and subgingivally when stain is light and/or root surfaces are exposed to air polishing. Evidence indicates that a standard supragingival air-polishing tip angled correctly (see Table 1 for technique tips) can remove subgingival biofilm and result in clinical findings in probing depths less than 4 mm during periodontal maintenance therapy20-22 (Figure 1); however, studies have indicated a device accommodating a subgingival nozzle can be effective for subgingival air polishing in pockets of 5 mm to 9 mm and in implants (Figure 2).23,25,28 FDA approval for use in the United States is limited to 5 mm probing depths or less, and HealthCanada approval for use in Canada is limited to 10 mm or less.

Effects on Soft and Hard Tissues, Restorations, and Dental Implants

Gingival bleeding and abrasion are the most common soft-tissue effects of air polishing with sodium bicarbonate or other traditional powders. Even though these outcomes are temporary, the tip of the air polisher should be pointed away from the gingiva to avoid tissue trauma when using more-abrasive air-polishing powders supragingivally. Even with glycine powder and a subgingival nozzle, 5 seconds per subgingival site and continuous movement are recommended to curtail damage to dental and periodontal tissues. When appropriate technique is used, there is no evidence of soft-tissue abrasion when using glycine powder in an air-polishing device.23,26

Use of traditional supragingival air-polishing powders should be minimized on all restorative materials (composite, gold, glass-ionomer, and amalgam). The lower abrasiveness and water solubility of glycine powder offer an advantage in cases with extensive restorative or cosmetic dental work. This powder is also preferred for treatment of implants and bacterially induced peri-implant mucositis or peri-implantitis.28,29 Additional evidence is evolving regarding prevention and treatment of peri-implant diseases.

Precautions for Safety

Air polishing can cause safety concerns for the patient and dental hygienist, although safety issues are fewer for the patient when using glycine powder. A patient's health and dental history should be reviewed (accompanied by an examination of the oral hard and soft tissues) before air polishing to ensure that air polishing is not contraindicated. Sodium-bicarbonate air-polishing powders are contraindicated for use in patients with hypertension, sodium-restricted diets, and end-stage renal disease. Regardless of powder selection, air polishing is contraindicated for individuals with respiratory diseases or immunosuppressed individuals. The patient should also remove contact lenses and wear eye protection to prevent the spray from entering the eyes. Any use of a pressurized handpiece would require a physician consultation for patients with severe respiratory disorders before air polishing.23 Although extremely rare, all instruments that use pressurized air (eg, high-speed handpiece, air-water syringe) present a risk of air emphysema. Risks can be minimized by following the manufacturer's instructions and using the appropriate air pressure, handpiece, and technique.

Additional health hazards can exist for patients and healthcare professionals due to the aerosols generated during air polishing. As with all aerosol-producing procedures, the practitioner should use a high-volume evacuation (HVE) device to reduce the spread of contaminated aerosols, as well as standard infection-control precautions. Dental hygienists should wear a well-fitting face mask with appropriate bacterial-filtration efficiency. Surfaces within 3 feet of the treatment area should be covered with disposable plastic drapes or disinfected with a high-level surface disinfectant.

Patient Education and Motivation

With the dental hygienist's assistance, patients should remove all visible biofilm to learn how to improve self-care practices before air-polishing procedures. Individualized education should connect tooth stains, biofilm, and calculus deposits and relate them to recommended changes in oral hygiene practices as well as lifestyle and diet.

For patients with tooth stains, gingival inflammation, or periodontal pockets, it is important to recommend powered toothbrushes, effective interdental cleaning aids selected collaboratively by the patient and the hygienist, and frequent professional prophylaxis or periodontal maintenance visits to reduce supra- and subgingival biofilm and potential for stains on the teeth. Goal setting, self-monitoring, and planning can be effective to reduce the potential causes of staining and improve oral hygiene.

Conclusion

In addition to potentially saving time and improving the patient experience, supra- and subgingival air polishing with glycine powder has proven effective for biofilm removal and periodontal health benefits as well as light stain removal. Given these benefits, combined with its ability to be safely used on restorations and prosthetics, including implants, dental hygienists may want to consider adding air polishing with glycine powder in their treatment plans as a therapeutic procedure to change the subgingival environment in patients with gingivitis, periodontitis, and peri-implant diseases.

About the Authors

Kristy Menage Bernie, RDH, MS, RYT, the director of Educational Designs and assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Francisco, in the MS-DH program, is an international speaker and on the editorial review board for the Journal of Dental Hygiene. Her professional memberships include the Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry, the American Dental Education Association, and the American Dental Hygienists' Association. She can be reached via www.EducationalDesigns.com.

Jennifer Pieren, RDH, MS, is a faculty member at Youngstown State University and a faculty expert and presenter for the ADHA National Board Review. Denise Bowen, RDH, MS, is professor emeritus at Idaho State University and an internationally renowned speaker and author. Bowen and Pieren are the co-editors of the upcoming Darby & Walsh Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice, 5th ed.

References

1. American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. Whitening survey. Summer 2012. https://www.aacd.com/proxy/files/Publications%20and%20Resources/Whitening%20Survey_Aug12(1).pdf. Accessed March 28, 2018.

2. American Dental Hygienists' Association. Policy manual. Glossary definition of optimal oral health, HOD, 1999. Chicago: ADHA, 2016.

3. FDI World Dental Federation. Oral health definition executive summary. 2016. https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/media/images/oral_health_definition-exec_summary-en.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2018.

4. Pieren JA, Bowen DM. Tooth polishing and whitening. In: Bowen DM, Pieren JA,eds. Darby and Walsh Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 5th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; ahead of print 2019.

5. Lazarchik DA, Haywood VB. Use of tray-applied 10 percent carbamide peroxide gels for improving oral health in patients with special-care needs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:639-646.

6. American Dental Hygienists' Association. Standards for clinical dental hygiene practice. Access. 2016;30(8):Supplement.

7. Menage Bernie K. Professional whitening: standards in practice. Access. 2011;25(10):12-15. http://www.adha.org/sites/default/files/7122_Phillips_Whitening.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2018.

8. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Tooth whitening/bleaching: treatment considerations for dentists and their patients. September 2009 (revised November 2010). https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/About%20the%20ADA/Files/whitening_bleaching_treatment_considrations_for_patients_and_dentists.pdf?la=en. Accessed March 28, 2018.

9. Mark AM. Getting whiter teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148:280.

10. Impressions: most Americans choose to whiten teeth at home. CA Dent Assoc J. 2012;40(12):914.

11. American Dental Association. Natural tooth whitening: fact vs. fiction. https://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/w/natural-teeth-whitening. Accessed March 28, 2018.

12. Brooks JK, Bashirelahi N, Reynolds MA. Charcoal and charcoal-based dentifrices. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148(9):661-670.

13.Carey CM. Tooth whitening: what we know. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14(Suppl):70-76.

14. Nathoo SA. The chemistry and mechanisms of extrinsic and intrinsic discoloration. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128(Suppl):6S-10S.

15. Al Quran FAM, Mansour Y, Al-Hyarl S, et al. Efficacy and persistence of tooth bleaching using a diode laser with three different treatment regimens. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2011;6:436-445.

16. Kim YM, Ha AN, Kim JW, Kim SJ. Double-blind randomized study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of over-the-counter tooth-whitening agents containing 2.9% hydrogen peroxide. Oper Dent. 2018;43(3):272-281.

17. Lee SS, Zhang W, Lee DH, Li Y. Tooth whitening in children and adolescents: a literature review. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27(5):362-368.

18. Bonafé E, Loguercio AD, Reis A, Kossatz S. Effectiveness of a desensitizing agent before in-office tooth bleaching in restored teeth. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18(3):839-845.

19. Kim Y, Son HH, Yi K, et al. Bleaching effects on color, chemical, and mechanical properties of white spot lesions. Oper Dent. 2016;41(3):318-326.

20. Sawai SA, et al. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:475-477.

21. Laleman I, Cortellini S, De Winter S, et al. Subgingival debridement: end point, methods and how often? Periodontol 2000. 2017;75(1):189-204.

22. Lu H, He L, Zhao Y, Meng H. The effect of supragingival glycine air polishing on periodontitis during maintenance therapy: a randomized controlled trial. PeerJ 6:e4371 2018; doi: 10.7717/peerj.4371.

23. Cobb CM, Daubert DM, Davis K, et al. Consensus conference findings on supragingival and subgingival air polishing. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2017;38(2):e1.

24. Simon CJ, Munivenkatappa Lakshmaiah Venkatesh P, Chickanna R. Efficacy of glycine powder air polishing in comparison with sodium bicarbonate air polishing and ultrasonic scaling - a double-blind clinico-histopathologic study. Int J Dent Hyg. 2015;13(3):177-183.

25. Petersilka GJ. Subgingival air-polishing in the treatment of periodontal biofilm infections. Periodontol 2000. 2011;55:124-142.

26. Beuhler J, Amato M, Weiger R, Walter C. A systematic review on the effects of air polishing devices on oral tissues. Int J Dent Hyg. 2016;14:15-28.

27. Riben-Grundstrom C, Norderyd O, Andre U, Renvert S. Treatment of peri-implant mucositis using a glycine powder air-polishing or ultrasonic device: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:462-469.

28. Schwarz F, Becker K, Sager M. Efficacy of professionally administered plaque removal with or without adjunctive measures for the treatment of peri-implant mucositis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(Suppl 16):S202-S213.

29. Schwarz F, Becker K, Bastendorf KD, et al. Recommendations on the clinical application of air polishing for the management of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Quintessence Int. 2016;47(4):293-296.

30. Zhao Y, He L, Meng H. Clinical observation of glycine powder air-polishing during periodontal maintenance phase. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2015;50:544-547.

31. Bühler J, Amato M, Weiger R, Walter C. A systematic review on the patient perception of periodontal treatment using air polishing devices. Int J Dent Hyg. 2016;14(1):4-14.