You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

The US population is becoming increasingly more diverse. According to data from the US Census Bureau, ethnic minorities account for almost one-third of the current US population and are expected to make up 54% of the total US population by 2050.1,2 These estimations suggest that in the near future, many patients seeking dental care will be from culturally and ethnically diverse groups.

The US Surgeon General’s Oral Health in America Report discusses how race and ethnicity play a role in a person’s ability to access oral healthcare.3,4 As a result, the US Health and Human Services (HHS) developed an action plan outlining the need for a workforce and healthcare system able to identify racial and ethnic health disparities and develop sensitivity for culture and ethnic differences.5 This action plan continues to be a top priority for HHS, as objectives in its Healthy People 2010 and Healthy People 2020 documents describe an oral health workforce that can meet the needs of all citizens of the United States.6,7

Cultural competence has been highlighted in the literature as a key component in addressing the needs of a diverse society and reducing health disparities among diverse populations.3-7 One of the most widely accepted definitions of cultural competency emerges from the pediatric mental health literature: “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency or amongst professionals and enables that system, agency or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.”8 The process by which students acquire the necessary attitudes, beliefs, and skills in order to deliver culturally competent care is known as cultural competency education (CCE).9-12

Educational and professional organizations have recognized the need for cultural competency education and responded through formal educational recommendations and standards.13-17 The American Dental Association encourages cultural competency amongst its members, stating that dental professionals must possess the expertise and skills needed to provide services to a growing diverse patient population.18 The American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) in its Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice document directs dental hygienists’ to recognize diversity and integrate cultural and religious sensitivity in all professional interactions.19 As the voice of dental educators, the American Dental Education Association contends that dental education institutions have a “distinct responsibility to educate dental and allied dental professionals who are competent to care for the changing needs of our society.”20

The accrediting body for dental and dental hygiene programs, the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA), has established accreditation standards addressing cultural competency education.16,17 CODA contends that “dental and dental hygiene graduates must possess the necessary interpersonal and communication skills needed to successfully interact with and further manage a diverse patient population.”16,17 Consequently, a newly revised Dental Hygiene Standard 2-15 was implemented January 1, 2013, and states, “dental hygiene graduates must be competent in interpersonal and communication skills to effectively interact with diverse population groups and other members of the healthcare team.”17 As a result of these recent initiatives, dental hygiene programs across the country are trying to identify the most effective means of incorporating this content into the curriculum.

CCE in the Curricula

Studies in medicine, dentistry, and other healthcare professions have been conducted to determine the extent to which CCE has been incorporated into professional programs.21-26 The literature suggests that most US dental schools have integrated some form of CCE into the dental curricula.23-25,27-30 A 2006 survey of US dental schools found that 91% of the responding dental schools had some form of cultural competency instruction in their curricula.24 The majority of these dental schools reported that cultural competency has been integrated into existing dental courses with specific goals and objectives.24,25 These results pre-date the newly revised CODA standards for dental and dental hygiene programs. Updated data is needed to identify if these statistics have changed since the implementation of the new CODA standards in 2013.

Conceptual Approaches for CCE

According to Betancourt et al, cultural competency education pedagogy can be divided into three conceptual approaches: cultural sensitivity approach, multicultural or categorical approach, and the cross-cultural approach.21 Each of these approaches concentrates on a different aspect of CCE, attitudes, knowledge, and skills.21 The cultural sensitivity approach focuses on the attitudes of the provider or student as they relate to culture influences of the patient and their health beliefs and practices.21 A 2008 dental study by Rubin et al employed this approach. Outcomes of that study found significant differences in student cultural competency attitudes after participating in service learning experiences.23

The multicultural or categorical approach of cultural competency focuses on the knowledge of values, beliefs, and behaviors of certain cultural groups.21 Because traditional educational methodologies, such as lectures and group discussions, are utilized in this approach to increase knowledge, it may be the easiest to utilize.21 This approach was used in a 2008 study by Pilcher et al to determine if curricular changes would increase dental students’ knowledge of cultural competency topics.27 In this study, students were asked to complete an online survey before and after exposure to the cultural competency content of the didactic components of the dental curriculum. Based on the findings, Pilcher et al concluded that curricular changes had produced changes in the students’ knowledge of cultural competency topics.27

Betancourt et al claim that the cross-cultural approach focuses on clinical skills related to the ability to care for diverse populations.21 Dental researchers Broder et al utilized this approach in their 2006 study employing trained patients or patient instructors to act out real-life cultural scenarios, coupled with self-reflection exercises to teach students how to effectively interview and communicate with patients in a clinical setting.28 These researchers concluded that the use of patient instructors is an effective instructional method for enhancing students’ interpersonal communication skills but not an effective tool for enhancing students’ clinical interviewing skills.28 Broder et al further concluded that the use of reflective learning after each patient instructor encounter is a critical element for students to recognize their own cultural biases, a key element in the cultural competency continuum.28

Instructional and Evaluation Methods for CCE

An array of instructional methods has been utilized by healthcare educational programs to teach CCE. Lectures/seminars seem to be the preferred curricular method.24,25 Case studies, small group discussions, and community outreach/service learning programs are also popular methods. To a lesser extent vignettes, problem-based learning, and role play exercises are also employed to teach cultural competency.24,25 Due to limited research on CCE in dental hygiene, very little is known about the instructional methods used by dental hygiene programs to teach CCE.

Like instructional methods, a variety of evaluation measures have been employed to assess student attainment of cultural competency. While several types of evaluation have been reported, each seems to be dependent on the approach used to teach CCE.22,24,27 According to their 2006 study of US dental schools, Saleh et al reported written examinations and direct observation by faculty to be the most common forms of evaluation.24 Gregorczyk et al concluded in a 2008 assessment of methods of evaluating CCE that “there are no widely accepted instruments to evaluate health professions students’ cultural competency knowledge.”31 What seems to be missing in the literature regardless of discipline, is long-term outcome assessment for cultural competency knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

The Need for CCE Research in the Dental Hygiene Curricula

While the literature suggests that CCE has been incorporated into professional healthcare programs, it provides little information regarding the status, strategies, and guiding measures of cultural competency education in US dental hygiene schools. Further studies are needed to examine to what extent dental hygiene programs are incorporating cultural competency education into the dental hygiene curriculum and if the characteristics of the dental hygiene program impact the degree to which cultural competency education is incorporated. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine the degree to which US dental hygiene programs are incorporating cultural competency education into the dental hygiene curriculum and to identify associated program characteristics.

Methods and Materials

A survey instrument patterned after previous dental studies by Saleh et al24 and Rowland et al25 was developed by the principle investigator and a team of experienced researchers. The questionnaire was distributed in electronic format to 334 dental hygiene program directors in the United States. The questionnaire consisted of 19 questions that covered topics related to curricular methods, evaluations measures, program goals and implementation of CCE as well as perception and demographic questions. While all questions were forced-choice for ease of data analysis, participants were given the opportunity to provide additional information for five questions. Following Institutional Review Board approval, the survey was pilot tested by five US dental hygiene program directors for question content, clarity, and understanding. Based on feedback received from the pilot group, revisions were made to the survey.

An invitation to participate in the study was electronically delivered to the email addresses of the 334 US dental hygiene program directors, which were obtained from ADHA. The email directed participants to a URL with instructions on how to access the questionnaire, complete the survey, and electronically return responses as provided by SurveyGizmo.com©. Two weeks after the initial email message was sent, a second message was sent to program directors inviting them to participate in the study if they had not already done so. All responses were anonymous to the principle researcher and delivered back via an Excel file created by SurveyGizmo©. All data values were provided in aggregate form. Data sets were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Additionally, Chi-Square analyses utilizing Statistics Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (IBM Corporation, 2011) were conducted on two questions to determine if relationships existed between several variables and programs that have CCE as an overall program learning outcome and specific learning objectives for community outreach/service learning programs.

Results

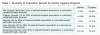

Sixty-eight (76%) Associate of Science programs and 21 (24%) Bachelors of Science programs returned the questionnaire for an overall response rate of 27%. Nearly half (47%) reported their last CODA site visit was within the last 3 years. While cultural competency encompasses far more than cultural, racial, and ethnic diversity, study participants were asked to rate the diversity of patient and student populations served by their institutions based on these factors alone. A close examination of Table 1 reveals that the majority of responding program directors (84%) rated the patient population served by their program as diverse, very diverse, or extremely diverse (20% or greater of patient population is culturally/racial/ethnically diverse). In contrast, 61% of program directors rated the student population served by their program as not diverse or slightly diverse (20% or less of student population is culturally/racial/ethnically diverse) (Table 1).

When asked about the presence of cultural competency in the curriculum, 91% reported that CCE has been incorporated into the curriculum in some manner, with 83% of programs reporting cultural competency is addressed as an overall program learning outcome. Only 9% of the responding programs reported that CCE had not been incorporated into the curriculum, with a majority (75%) reporting plans to incorporate CCE in the future. Of the programs that had already incorporated CCE into the curriculum, three top reasons were given for doing so, including:

1. Reporting diverse patient populations served by the program (54%)

2. Reporting accreditation requirements (35%)

3. Reporting leadership/administration commitment to cultural competency/diversity issues (23%)

Conversely, of the remaining 9% that indicated that their programs had not incorporated CCE, 50% of those reported not having enough curricular time to cover topics. Additionally, 43% reported a lack of faculty expertise or training in the subject matter, and 33% indicated limited financial resources as their primary reasons for not incorporating CCE into the curriculum.

Program directors were asked several questions relating to their program’s CCE curriculum, including primary approach or goals (skills, attitudes, and knowledge) for CCE, types of courses offered, as well as teaching and evaluation methods for CCE. Improvement of students’ skills to treat diverse patient populations (52%) was the most reported approach or goal for CCE, followed by increasing students’ attitudes or self-awareness of prejudices or biases towards other cultures (32%) and enhancing student’s knowledge of other cultures (11%). A select few (5%) indicated that their programs did not have a specific approach or goal for their CCE curriculum.

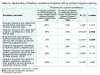

Seventy-two percent of the responding program directors reported CCE has been incorporated into existing dental hygiene courses with specific goals, objectives, and evaluation methods for cultural competency. Twenty-eight percent reported CCE had been incorporated into existing dental hygiene courses but without specific goals, objectives, and evaluation methods for cultural competency. Only 8% indicated that CCE had been incorporated into a separate, independent dental hygiene course. Lectures/seminars (83.1%) and community outreach programs (76.4%) were the most frequently reported teaching methods for CCE. Problem-based learning (25.8%) and the use of videos or vignettes (21.8%) were the least frequently reported teaching methods (Table 2).

Ninety-nine percent of the responding program directors indicated that their students participate in some type of community outreach/service learning program. A variety of community outreach/service learning projects were reported, with health fairs (86%) topping the list (Table 3). Fifty-four percent of the programs reported having specific learning objectives related to cultural competency for community outreach/service learning activities, however numerous directors (42%) indicated that their students are not formally evaluated during community outreach/service learning projects. A small group (19%) indicated that their students are evaluated in all three constructs: attitudes, skills, and knowledge.

Participants were asked a number of perception questions related to the incorporation of CCE into the curriculum. A Likert scale ranging from very effective (1) to very ineffective (5) was utilized for program directors to rate incorporation of CCE into the curriculum. A large majority (85%) felt that their program had been effective or very effective at incorporating CCE into the existing dental hygiene curriculum. When asked to rate the importance of CCE to their dental hygiene program, 93% rated CCE as important or extremely important.

The Fishers Exact Test was conducted to determine if relationships existed between several program demographics and the responses given. Table 4 summarizes the proportions of programs with or without program learning outcomes for cultural competency across several different program characteristics. Statistically significant relationships were found between programs that had program learning outcomes for CCE and directors who rated their programs’ incorporation of CCE into the curriculum as effective or highly effective (x^2 = 28.046, P = .000). Programs that had program learning outcomes for CCE were also more likely to have specific learning objectives for CCE in community outreach/service learning programs (x^2 = 12.651, P = .000). This suggests that programs that have overall program learning outcomes for CCE are more likely to perceive that their program had effectively incorporated CCE into the curriculum and have specific learning objectives for CCE in community outreach programs. Type of degree awarded, diversity of patient or student population, and directors’ rating of importance of CCE was not associated with having program learning outcomes for CCE.

Table 5 shows the proportional relationships between programs with or without specific learning objectives for CCE for community outreach/service learning programs and several program characteristics. A statistically significant relationship was found between programs that had specific learning objectives for CCE in community outreach/service learning programs and programs that indicated that CCE was addressed as one of its overall program learning outcomes (x^2 = 12.651, P = .000). Programs that had specific learning objectives for CCE in community outreach/service learning programs were also more likely to have program directors who rated incorporation of CCE into the curriculum as effective or very effective (x^2 = 12.83, P = .000) and have very diverse or extremely diverse patient populations (x^2 = 4.805, P = .048). Type of degree awarded, diversity of student population, or directors’ rating of importance for CCE had no impact on whether or not a program had specific learning objectives for CCE in community outreach/service learning programs.

Discussion

With an increasingly diverse population, coupled with a very slow increase in the diversity of students in the allied health professions, the need to educate a workforce that can better address the oral healthcare needs of a diverse society is critical.1-7,25 As per accreditation standards, today’s dental hygiene graduates must possess the interpersonal and communication skills needed to successfully interact with and manage a diverse patient population.17 This study sought to examine the level to which US dental hygiene programs are incorporating CCE into the curriculum.

Results of this study indicate that more dental hygiene programs have incorporated CCE into the curriculum (91%) than those that have not (9%). Similar to dental schools24,25 most (72%) dental hygiene schools incorporate CCE into other courses with specific goals, objectives, and evaluation measures for cultural competency. The results of this study are comparable to the 2006 study findings by Saleh et al, who reported that only 4.5% of US dental schools offer a separate, independent course in cultural competency.24 Similarly, this current study revealed that 8% of the reporting programs offer a separate, independent course. Due to the self-reporting nature of this study, programs may over- or under-rate their incorporation of CCE. However, the findings do suggest that dental hygiene programs find cultural competency to have value and relevance.

Demographic findings related to diversity of patient and student populations were not surprising. The results, like the results from previous dental studies,24,25 hint at a diverse patient population being served by a dental hygiene student population that lacks cultural and ethnic diversity. Further research is warranted to investigate why students from ethnically and racially diverse populations are not seeking allied health professions such as dental hygiene as a career choice.

The reasons for incorporating CCE into the curriculum were also not surprising. Serving a diverse patient population was the most frequently reported reason for incorporating CCE, followed by accreditation requirements. It would appear that dental hygiene programs are aware of and responding to the needs of their patients by including cultural competency topics into the curriculum. Since 47% of the responding programs had a CODA site visit within the last 3 years, this might suggest dental hygiene programs are responding to recent accreditation standard changes relating to cultural competence issues.17

This study elicited program directors’ perceptions on CCE and if these perceptions translate to incorporation of CCE into the curriculum through program learning outcomes, teaching methods, and evaluation measures. Study findings on perception questions imply that program directors appreciate CCE and most perceive CCE to be an important aspect of the dental hygiene curriculum. The findings also allude to a perception from program directors that their own programs have effectively incorporated CCE into the curriculum, which may be a reason for the majority of programs indicating they have CCE addressed as an overall program learning outcome and have community outreach/service learning programs with objectives for CCE. Further long-term investigations are warranted to see if positive correlations can be established between directors’ perceptions of CCE and the incorporation of CCE into the curriculum.

A 2003 medical study by Dolhun et al22 and 2006 dental studies by Saleh et al24 and Rowland et al25 revealed considerable variations in curricular approaches and course content related to CCE in US medical and dental schools. This study of US dental hygiene programs yielded similar results finding dental hygiene programs to be employing an array of curricular methods to teach CCE. Like the findings from earlier studies on CCE in professional programs,24,25 most dental hygiene programs (83%) rely on lectures/seminars to introduce cultural competency concepts. Pilcher et al concluded lectures/seminars enhance knowledge of CCE concepts.27 With over half of the programs (52%) indicating that their program’s primary goal for CCE is to improve students’ skills to treat diverse populations, clearly dental hygiene programs need to align their teaching methods to their CCE curriculum goals. The findings from this study indicate that 76% of programs have their students participate in some type of community outreach/service learning programs, which, according to Betancourt et al, do enhance skills.21 However, these results point to a wide variance in the type of community outreach/service learning programs employed by US dental hygiene programs (Table 3). Of further interest is the fact that 54% of programs have specific learning objectives for CCE in community outreach/service learning programs but much fewer (42%) go on to evaluate their students during these programs. This finding could be problematic for dental hygiene programs, as it is up to individual programs to demonstrate accreditation standards related to CCE are being met. Further studies need to focus efforts on determining how programs are evaluating cultural competency knowledge, skills, and attitudes of students. Although cultural competency skills and attitudes can often be difficult to access and evaluate, the importance of outcome assessment cannot be understated, as the results of this study indicate that dental hygiene programs could be lacking in this area. Additional research is indicated to determine the long-term effects of dental hygiene programs’ efforts to incorporate cultural competency education into the curriculum.

Other studies have not investigated program directors’ perceptions of effectiveness of incorporation of CCE. As expected, the results of this study indicate that programs that had overall program learning outcomes for CCE were more likely to have directors who feel that they had effectively incorporated CCE into the curriculum. They were also more likely to have specific learning objectives related to CCE in community outreach programs. The results suggest that program director’s perception of importance of CCE, student diversity, and type of degree awarded by the program had no influence on a program’s program learning outcomes status and specific learning objectives for community outreach/service learning programs. One might expect that a program with a diverse patient population would have program learning outcomes for treating a diverse population. Surprisingly, this study found that a program’s program learning outcomes status was not affected by program demographics such as patient diversity. This study did however find a positive correlation between programs that had specific learning objectives for community outreach/service learning programs and having a diverse patient population. Similar correlations were found by dental researchers Rowland et al who concluded that dental schools are offering CCE courses to meet the needs of a diverse patient population. The results of this study are promising and suggest that dental hygiene programs are incorporating CCE into their existing curricula.

This study is limited by the self-reporting nature of the study and overall response rate of 27%. The timing and electronic distribution of this survey, as well as large numbers of survey requests that directors receive may be responsible in part for the low response rate. This survey was emailed to each US dental hygiene program director in the first part of the spring semester. Future researchers should consider mailing surveys and conduct follow-up personal interviews, which may increase the overall response rate.

Conclusion

In this descriptive study of CCE in US dental hygiene schools, the findings suggest that US dental hygiene programs value CCE and are making efforts to incorporate CCE into the curriculum. Variations in teaching methods and evaluation for CCE measures were found. In addition to differences in teaching methodology, this study found that dental hygiene programs rely on community outreach/service learning as a way of introducing CCE concepts without formal evaluation of knowledge, skills, or attitudes. This finding provides evidence that further research is needed to determine if dental hygiene programs are sending their students to community outreach/service learning programs as a way to meet new accreditation requirements for CCE and/or simply as a way to enhance the students’ sensitivity to cultural competency as a whole. Further long-term studies are warranted and should be aimed at determining the extent and effectiveness of community outreach/service learning programs to produce changes in students’ attitudes, skills, and knowledge as they relate to CCE. Additionally, further studies are indicated in the area of outcome assessment for CCE to determine if the curricular methods employed by dental hygiene programs are making a difference in the cultural competency of US dental hygiene students. The focus of further studies should be on types of assessments or evaluation methods used to measure cultural competency. This may assist in the development of and establishing standards for incorporating CCE into the curriculum. Future research efforts should also be directed at identifying potential barriers that may hinder diverse student populations from seeking dental hygiene as a profession.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Danette R. Ocegueda, RDH, MS, is the Professional Educator Manager-West for Philips Oral Healthcare and an adjunct clinical professor in the Department of Dental Hygiene at Sacramento City College. Christopher J. Van Ness, PhD, is a research associate professor and Director of Assessment, Department of Public Health and Behavioral Science at the University of Missouri- Kanas City, School of Dentistry. Carrie L. Hanson, RDH, MS, EdD, is Director of Dental Hygiene at Johnson County Community College. Lorie A. Holt, RDH, MS, is an associate professor and Director of Degree Completion Studies, Division of Dental Hygiene at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Dentistry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The principle investigator would like to thank Arturo Baichii, PhD, for his guidance and assistance with data analysis of this project.

REFERENCES

1. Humes HR, Jones NA, Ramirez, RR. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010. US Bureau of the Census, 2010 Census Data. The United States Census Bureau [Internet]. 2011 March [cited 2012 March 23]. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf.

2. US Census Bureau Projections Show a Slower Growing, Older, More Diverse Nation a Half Century from Now. The United States Census Bureau [Internet]. 2012 December 12 [cited 2016 March 11]. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial research, National Institutes of Health. 2000.

4. Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academic Press. 2002.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities: A Nation Free of Disparities in Health and Health Care. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health [Internet]. 2011 April [cited 2016 March 11]. http://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/files/Plans/HHS/HHS_Plan_complete.pdf.

6. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2000.

7. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2014.

8. Cross TL, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Isaacs MR. Toward a culturally competent system of care. Volume one: a monograph of effective service for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center. 1989.

9. Hobgood C, Sawning S, Bowen J, Savage K. Teaching culturally appropriate care: A review of educational models and methods. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(12):1288-1295.

10. Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence care in the delivery of healthcare services: A model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181-184.

11. Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117-125.

12. Wagner JA, Badwal DR. Dental students’ beliefs about culture in patient care: self-reported knowledge and importance. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(5):571-576.

13. Accreditation Standards. Liaison Committee on Medical Education [Internet]. [cited 2012 October 25]. http://lcme.org/publications.

14. AACN position statement: Diversity and equality of opportunity. American Association of Colleges of Nursing [Internet]. 1997 [cited 2012 October 25]. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/Publications/positions/diverse.htm.

15. Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing. ACEN Accreditation Manual: Section III Standards and Criteria Glossary. Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 October 5]. http://www.acenursing.net/manuals/SC2013.pdf.

16. Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental education programs. Standard 2-16. American Dental Association [Internet]. [cited 2016 March 15]. http://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/2016_predoc.pdf?la=en.

17. Commission on Dental Accreditation. American Dental Association Accreditation standards for allied dental education programs/dental hygiene. Standard 2-15. Chicago. American Dental Association [Internet]. [cited 2016 March 15]. http://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/DH_Standards.pdf?la=en.

18. Future of Dentistry. American Health Policy Resources Center. American Dental Association [Internet]. [cited 2012 March 23]. http://www.ada.org/en/~/media/ADA/About%20the%20ADA/Files/future_execsum_fullreport.

19. ADHA standards for clinical dental hygiene practice. American Dental Hygienists’ Association [Internet]. [cited 2016 March 11]. https://www.adha.org/resourcdocs/7261_Standards_Clinical_Practice.pdf/.

20. American Dental Education Association. Position Paper - Statement of the roles and responsibilities of academic dental institutions in improving the oral health status of all Americans. J Dent Educ. 2004;68(7):759-767.

21. Betancourt JR, Cervantes MC. Cross-cultural medical education in the United States: Key principles and experiences. Kaohswing J Med Sci. 2009;25(9):471-478.

22. Dolhun, EP, Munoz, C, Grumbach, K. Cross-cultural Education in U.S. Medical Schools: Development of an assessment tool. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):615-622.

23. Rubin RW, Rustveld LO, Weyant RJ, Close JM. Exploring dental students perceptions of cultural competency and social responsibility. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(10):1114-1121.

24. Saleh L, Kuthy RA, Chalkey Y, Mescher KM. An assessment of cross-cultural education in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(6):610-623.

25. Rowland ML, Bean CY, Casamassimo PS. A snapshot of cultural competency education in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(9):982-990.

26. Chapman S, Bates T, O’Neil E, et al. Teaching cultural competency in allied health professions in California. Center Health Profess. 2008:1-5.

27. Pilcher ES, Charles LT, Lancaster CJ. Development and assessment of a cultural competency curriculum. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(9):1020-1028.

28. Broder HL, Janal M. Promoting interpersonal skills and cultural sensitivity among dental students. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(4):409-416.

29. Wagner J, Arteaga S, D’Ambrosio J, et al. Dental students’ attitudes towards treating diverse patients: Effects of a cross-cultural patient-instructor program. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(10):1128-1134.

30. Hewlett ER, Davidson PL, Nakazono TT, et al. Effect of school environment on dental students’ perceptions of cultural competency curricula and preparedness to care for diverse populations. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(6):810-818.

31. Gregorczyk SM, Bailit HL. Assessing the cultural competency of dental students and residents. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(10):1122-1127.