You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Research in medical settings reports that patients’ satisfaction with their provider is an important predictor of their willingness to return for follow-up visits, their cooperation with treatment recommendations, and the likelihood that they recommend their provider to other patients.1-3 Several studies in dentistry have shown similar findings. For example, Patel et al concluded that the relationship with a periodontist was related to patients’ decision to accept a recommendation to have surgical treatment.4 Inglehart et al documented that the level of satisfaction with their dentist affected whether and how long patients had used a bite splint they had received because they suffered from bruxism.5 Numerous other studies provided additional support for the importance of dental patients’ satisfaction with their provider, for reducing patients’ dental fear and anxiety, for increasing their confidence in their dentist, and for achieving more positive treatment outcomes.6-14

One aspect of a patient visit that was identified as having a negative effect on patients’ satisfaction with their provider was the length of time the patients spent in a waiting room. This relationship was documented for patients in many different medical settings, such as when seeking care in emergency rooms, receiving chemotherapy treatment, visiting a primary care provider, or a gynecologist, obstetrician, or other medical specialists.15-20 In dental offices, patients’ dissatisfaction with long waiting times has been documented as well.21-23 However, no study so far explored how the exact length of the patient’s time in the waiting room would affect their satisfaction with their provider, their intentions to cooperate with treatment recommendations, and their intentions to return for future dental visits. The first objective of this study is to explore if having a long waiting time versus not having to wait or having a dentist who is early affects a patient’s response to their providers and their intended treatment cooperation.

In addition to exploring this relationship in general, it is also interesting to reflect whether certain groups of patients will respond to longer waiting times more negatively than other groups of patients. One potential moderating factor could be the patient’s level of education. Research found that there is a general relationship between patient satisfaction and level of education. Patients with lower levels of education were on average more satisfied with their medical care and providers than patients with higher levels of education.24-26 In the context of exploring the effects of length of waiting time on dental patients’ satisfaction, these earlier findings might not only result in the prediction that less educated patients would be more satisfied than better educated patients, but there might be a differential effect of waiting time length in these groups. The second objective is to explore whether a patient’s level of formal education (more precisely, the years of schooling they had received) will differentially affect their satisfaction as a function of the length of their waiting time. It is hypothesized that patients with more formal education will be less satisfied than patients with less formal education, and that this effect would be especially large when patients had a long waiting time.

A second moderating factor might be whether a dental visit is a patient’s first encounter with a provider or whether a patient has an already established relationship. At a new-patient visit, dental care providers do not only need to assure that they collect all the necessary medical and dental information to provide safe and the best possible care for a patient, but they also have to develop good rapport with a patient. The question is how the length of waiting time affects a new patient versus an established patient’s response to their providers.

Methods and Materials

This research was determined to be exempt from oversight by the Institutional Review Board for the Health and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

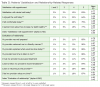

Respondents: An a priori power analysis with the program package G*Power 3.1.2 was conducted to compute the needed sample size given alpha = 0.05, the power = 0.95, and a medium effect size of 0.20 when using a univariate of analysis to test for significant differences in the average responses of respondents whose provider was early, late, or on time. The result showed that a sample size of 390 patients was needed. Data were collected from 399 regularly scheduled adult dental/dental hygiene patients. Table 1 shows that the sample was quite heterogeneous in regard to gender, age, and years of education. There were approximately equal numbers of male (n = 196) and female (n = 203) patients. The patients ranged in age from 19 to 93 years (mean = 52 years), and their years of education ranged from 6 to 30 years (mean = 14 years).

Procedure: The patients were informed about the study when they arrived for a regularly scheduled appointment in the waiting room area of a Midwestern dental school. If they agreed to respond to a self-administered survey after their appointment, they received the survey and a voucher for free parking during the visit from the research assistant. They responded to the anonymous survey after their appointment and returned it in a sealed envelope to the research assistant. The return of the survey was seen as giving implicit consent. No written consent was required because the survey was anonymous.

Materials: A survey instrument was developed by the research team and then pilot tested with a group of 10 patients. The pilot data showed that the questions were easy to understand and that only formatting changes were needed. The final survey consisted of four sets of questions. The first set asked the patients about some background characteristics such as their gender, age, years of education, and whether this dental visit was their first visit with this provider. Part 2 consisted of two questions related to the length of their waiting time. Question 1 inquired about the length of the waiting time in minutes, and Question 2 asked the patients to indicate categorically if their student provider was early, on time, or late for their appointment.

The third set of questions was concerned with the patients’ satisfaction with the appointment. The first of these four satisfaction questions asked about the patient’s “Satisfaction with the dental visit today,” with answers ranging from 1 = Not at all to 5 = Very satisfied. Three additional questions had a Likert-style answer format. They consisted of the statements “I enjoyed the visit today,” “I felt comfortable today,” and “I learned more about how to keep my teeth healthy.” Answers ranged from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. The Cronbach alpha inter-item consistency reliability coefficient for these four items was 0.763.

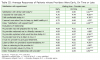

The final set of questions consisted of eight Likert-type questions concerning the patients’ evaluations of their relationship with their provider and their responses related to cooperating with their provider’s recommendations (“I plan to follow my provider’s recommendations”) and their likelihood to return to the provider (“I plan to return to this provider”). These answers also ranged from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. Table 2 provides an overview of the wording of these statements. The Cronbach alpha inter-item consistency reliability index for these eight items was 0.962.

Statistical analyses: The data were entered into SPSS (Version 21). Descriptive statistics such as percentages, means, standard deviations, and ranges were provided to give an overview of the responses. Inferential statistics were used to compare the responses of subgroups of patients. Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) with the three independent variables “Length of waiting time” (with the three levels: Provider was late, on time, or early), “Education” (≤ 12 years of education vs. > 12 years of education), and “Type of visit” (first vs. repeat visit), and the dependent variables satisfaction with appointment (four items) and evaluations or relationship with provider (eight items) were computed. An index “Satisfaction with the appointment” and an index “Evaluation of the patient-provider relationship” were calculated by averaging the responses to the single items in these two item sets. The inter-item consistency of these two scales was determined with Cronbach alpha coefficients. Univariate analyses of variance with the independent variable “Waiting time,” “Level of education,” and “First vs. not first visit” and the two indices as the dependent variables were conducted. A level of P < .05 was accepted as significant.

Results

Table 1 shows that 196 male and 203 female patients participated in this study. The patients were on average 52 years old (range 19 to 93 years) and had an average of 14 years of education (range 6 to 30 years), with 151 patients having a high school diploma or fewer years of education and 221 having more years of education than a high school diploma. Nine percent of the patients reported that this was their first visit to the dental school, and 29% indicated that it was the first visit with this particular student provider. When the patients were asked how long they had to wait in the waiting room area, the average answer was 8.59 minutes (range 0 to 75 minutes). In response to the question whether their provider had been early, on time, or late, 17% reported that their provider was early, 75% that their provider was on time, and 9% that their provider was late (Table 1).

The vast majority of patients was very satisfied with their dental visit (83%), agreed strongly that they enjoyed their visit (64%), had felt comfortable (75%), and had learned more about how to keep their teeth healthy (77%) (Table 2). When a satisfaction index was constructed by averaging the responses to these four items, the average response was 4.64 on a 5-point scale with 5 being the most satisfied response. The responses to the eight items that measured the patients’ evaluations of their relationship with their provider and their intentions to follow treatment recommendations and return for a follow-up visit were also very positive. Again, over 80% of the respondents strongly agreed that their provider was well prepared, welcomed them in a friendly manner, explained what would be done, and took time to listen to them. Over 80% also trusted their provider, planned on following the provider’s recommendations and returning to the provider, and felt their provider valued their time. When an index was constructed based on the average of the responses to these eight items, the average response was 4.83.

The first objective was to compare the responses of patients who had reported that their provider had been early, on time, or late. Table 3 shows that the patients whose provider was early were significantly more satisfied with their dental visit than the patients whose provider was on time, and that the least satisfied patients were those whose provider was late for the appointment (4.96 vs. 4.80 vs. 4.21; P < .001). The same pattern of responses was also found in the answers to the statements “I enjoyed the visit today,” “I felt comfortable today,” and “I learned more about how to keep my teeth healthy.” In each instance, patients whose provider was late were least positive in their responses, and the patients whose provider was early were most positive (MANOVA: F(4/754) = 5.15; P < .001). A univariate analysis of variance with the dependent variable “Satisfaction with appointment” index showed the same overall pattern of responses.

Table 3 also shows that the three groups of respondents whose providers were early, on time, or late differed in the same way in their evaluations of their relationship with their provider. For each of the eight statements, patients whose provider had been late were significantly less positive about their relationship than patients whose providers were early or on time (MANOVA F(16/742) = 2.51; P = .001).

In addition to comparing the responses of patients whose providers were early, on time, or late, it was also explored how the patients’ level of education affected the responses of these three groups. Figure 1 shows the average level of satisfaction of patients with lower (12 years or less) vs. higher (more than 12 years) levels of education in each of the three waiting time groups. This figure shows that patients with a lower level of education were more satisfied in each of the three groups than patients with higher levels of education (4.82 vs. 4.48; P < .001). In addition, patients with a higher level of education whose provider was late were on average least satisfied with their appointment (mean: 4.07) compared to all other groups (P < .01). Table 4 provides the detailed information concerning the effects of level of education on satisfaction and provider evaluations of patients in the three groups. Patients with lower levels of education had more positive average overall evaluations of their relationship with their provider than patients with higher levels of education (4.91 vs. 4.71; P < .01). While the interaction effects between the factors “Waiting time” and “Level of education” were not significant for most of the evaluation items, the average responses to the item “I feel that my provider values my time” showed again that patients with higher levels of education were least positive in response to this item compared to all other groups.

The final question was whether the fact that a patient had a first visit with a provider affected their responses to whether their provider was early, on time, or late. Figure 2 shows that the average overall evaluations of patients whose provider had been late and for whom this visit was a first visit were least positive (mean: 4.40), while the responses of patients with a first visit whose provider were early were most positive (mean: 5.00) compared to the evaluations of all other respondents. Table 5 shows that the fact that a patient had a first vs. not a first visit with a provider did not affect how satisfied they were, how much they enjoyed the visit, and how comfortable they felt. However, patients with a first visit agreed less strongly that they had learned more about how to keep their teeth healthy than patients for whom this visit was a repeat visit. In addition, patients who saw providers for the first time agreed less strongly that their provider was well prepared for their visit, welcomed them in a friendly manner, explained what would be done during the visit, took time to listen, and valued their time than patients for whom this visit was not a first visit with this provider. Patients with a first visit whose provider was late had the least positive response to the statements “My provider explained what would be done today” and “My provider took time to listen” compared to all other respondent groups.

Discussion

Patients’ satisfaction with their medical and dental visits and their provider is crucial for their willingness to cooperate with treatment recommendations, to return for a follow-up visit, and to recommend a provider to other patients.1-5 While a lack of treatment cooperation ultimately might affect patients’ health, not returning for follow-up appointments and not recommending a provider to other patients can clearly affect the success of a dental practice.5 Avoiding situations that negatively affect patients’ satisfaction is therefore crucial. The results of this study showed that letting patients wait for their appointments and not being on time affects their satisfaction negatively. Managing appointment times carefully is therefore important. However, there are times when patients might have to wait due to unforeseen events. The way these situations are being managed seem to determine ultimately how much the length of waiting affects patients’ satisfaction, at least in the short term. Research in medical settings found that when medical care providers were late for their appointment with a patient, spending more time with the patient during the appointment could moderate the negative effects of a long waiting time.19,27,28

The results of this study showed that patient characteristics might also affect the degree to which longer waiting times affect patients’ satisfaction. While previous research clearly documented that patients’ level of education was related to their treatment satisfaction,24-26 this is the first study that documents that patients’ level of education might moderate their responses to longer waiting times. In addition, there is some evidence that whether a dental visit is a new patient visit could further moderate patients’ responses. Future studies could explore whether other patient characteristics such as patients’ age might also affect responses to longer waiting times.29

In addition to considering how longer waiting times affect patients’ responses, it is also noteworthy to consider that research showed that providers’ satisfaction with an appointment was also lower when they could not provide on-time care for their patients and the patients had to wait.18 Running late for appointments might induce stress that affects patient-provider interactions and providers’ professional quality of life. In summary, longer waiting times for patients are not only likely to result in reduced patient and provider satisfaction in a given situation, but might affect the success of a practice in the long run.

This study had several limitations. First, the data were collected in a dental school setting where dental care is relatively less expensive but takes longer than in a private office. Answers to the question concerning the patients’ intent to return might be affected by the fact that they were seeking dental treatment for a reduced price. In private practice settings, patients’ intentions to return to a provider, especially if a dental visit is their first visit, might therefore be more affected by their level of satisfaction with an appointment. Second, given that these data were collected in a dental school, the patients might be more likely to come from a lower socio-economic background. Future research might therefore consider patients’ economic situation in connection with their level of education as a factor that might determine the patients’ responses to long waiting times. Third, no data were collected concerning whether these patients were treated by dental or dental hygiene students. It is therefore not possible to answer the question whether a longer waiting time for an appointment with a dental hygienist vs. a dentist would affect patients’ responses differentially. Finally, all dependent variables were assessed with patients’ responses to a survey. In future studies, it would be interesting to collect objective data such as whether patients actually return to a provider after having had to wait for a long time. In addition, several possible variables that might have affected the outcomes such as the procedure performed and the amount of experience of the provider were not included and should be considered in future studies. Assessing patients’ responses at later points in time could also be helpful because it would clarify if the findings in this study hold up over time.

Conclusion

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that the length of time patients have to wait in a waiting room area for their dental care provider negatively affects their level of satisfaction with the appointment, their evaluations of the patient-provider relationship, as well as their intentions to cooperate with the providers’ recommendations. These negative effects on patients’ level of appointment satisfaction are especially severe for patients with higher levels of education. In addition, if a provider is late for a first visit with a new patient, it can be expected that the patient’s overall evaluations of the patient-provider relationships will be least positive compared to the evaluations of all other patient groups.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Marita Rohr Inglehart, Dr. phil. habil, is a Professor, Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry & Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychology, College of Literature, Science & Arts, University of Michigan. Alexander H. Lee, BS, is a Research assistant, University of Michigan – School of Dentistry. Kristin G. Koltuniak, BS, RDH, is a dental hygienist in private practice of Dr. Diana Wolf Abbott, DDS, MS, PC, in Rochester Hills, MI. Taylor A. Morton, RDH, BS, is a dental hygienist in private practice at Children’s Dental Specialists in Warren, NJ. Jenna M. Wheaton, RDA, RDH, BSDH, is a dental hygienist in private practice at Shortt Dental in South Lyon, MI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank Chukwuka Akunne, Gopaldeep Kaur, Elizabeth Ly, and Paul Yoon for their help with collecting the data and preparing the data for analysis.

References

1. Federman AD, Cook EF, Phillips RS, et al. Intention to discontinue care among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):668-674.

2. Wartman SA, Morlock LL, Malitz FE, Palm EA. Patient understanding and satisfaction as predictors of compliance. Med Care. 1983;21(9):886-891.

3. Halfon N, Moira I, Ritesh M, Lynn MO. Satisfaction with health care for young children. Pediatrics.2004;113(6):1965-1972.

4. Patel AM, Richards RS, Wang H, Inglehart MR. Surgical or non-surgical periodontal treatment? Factors affecting decision making. J Periodontol. 2006;77(4):678-683.

5. Inglehart MR, Widmalm SE, Syriac PJ. Occlusal splints and quality of life – does the quality of the patient-provider relationship matter? Oral Health Prev Dent. 2014;12(3):249-258.

6. Kim JS, Boynton JR, Inglehart MR. Parents’ Presence in the operatory during their child’s dental visit: a person-environmental fit analysis of parents’ responses. Ped Dent. 2012;34(5):337-343.

7. Okullo I, Astrom AN, Haugerjorden O. Influence of perceived provider performance on satisfaction with oral health care among adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32(6):447-455.

8. Shouten BC, Eijkman MA, Hoogstraten J. Dentists’ and patients’ communicative behavior and their satisfaction with the dental encounter. Community Dent Health. 2003;20(1):11-15.

9. Sondell K, Soderfeldt B, Palmqvist S. Dentist-patient communication and patient satisfaction in prosthetic dentistry. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15(1):28-37.

10. Hottel TL, Hardigan OC. Improvement in the interpersonal communication skills of dental students. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(2):281-284.

11. Corah N, O’Shea R, Bissell G. The dentist-patient relationship: perceptions by patients of dentist behavior in relation to satisfaction and anxiety. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;111(3):443-446.

12. Corah N, O’Shea R, Bissell G, et al. The dentist-patient relationship: perceived dentist behaviors that reduce patient anxiety and increase satisfaction. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;116(1):73-76.

13. Van der Molen HT, Klaver AA, Duyx MP. Effectiveness of a communication skills training programme for the management of dental anxiety. Br Dent J. 2004;196:101-107.

14. Carey JA, Madill A, Manogue M. Communication skills in dental education: A systematic research review. Eur J Dent Educ.2010;14(2):69-78.

15. Booth AJ, Harrison CJ, Gardener GJ, Gray AJ. Waiting times and patient satisfaction in the accident and emergency department. Arch Emerg Med. 1992;9(2):162-168.

16. Thompson DA, Yarnold PR. Relating patient satisfaction to waiting time perceptions and expectations: the disconfirmation paradigm. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2(12):1057-1062.

17. Spaite DW, Bartholomeaux F, Guisto J, et al. Rapid process redesign in a university based emergency department: decreasing waiting time intervals and improving patient satisfaction. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(2):168-177.

18. Kallen MA, Terrell JA, Lewis-Patterson P, Hwang JP. Improving wait time for chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic at a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Prac. 2012;8(1):e1-e7.

19. Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait? the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(31):1-5.

20. Patel I, Chang J, Srivastava J, et al. Patient satisfaction with obstetricians compared with other specialties: analysis of us self-reported survey data. Patient Relat Outcome Meas.2011;2(21):21-26.

21. Chu CH, Lo EC. Patients’ satisfaction with dental services provided by a university in Hong Kong. Int Den J. 1999;49(1):53-59.

22. Al-Mudaf BA, Moussa MA, Al-Terky MA, et al. Patient satisfaction with three dental specialty services: a centre-based study. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12(1):39-43.

23. Tuominem R, Eriksson AL. Patient experiences during waiting time for dental treatment. Acta Odontol Scand. 2012;70(1):21-26.

24. Hall JA, Dornan MC. Patient sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with medical care. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(7):811-818.

25. Anderson LA, Zimmerman MA. Patient and physician perceptions of their relationship and patient satisfaction: a study of chronic disease management. Patient Educ Couns. 1993;20(1):27-36.

26. Schutz SM, Lee JG, Schmitt CM, et al. Clues to patient dissatisfaction with conscious sedation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(9):1476-1479.

27. Camacho F, Anderson RT, Safrit A, et al. The relationship between patient’s perceived waiting time and office-based practice satisfaction. NC Med J. 2006;67(6):409-413.

28. Feddock CA, Hoellein AR, Griffith III CH, et al. Can physician improve patient satisfaction with long waiting times? Eval Health Prof. 2005;28(40):40-52.

29. Kong MC, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. Correlates of patient satisfaction with physician visit: differences between elderly and non-elderly survey respondents. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(62):1-6.