You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

The American Dental Association's 1996 Preventive Health Statement on Nutrition and Oral Health "encourages dentists to maintain current knowledge of nutrition recommendation such as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans as they relate to general and oral health and disease." This statement also encourages dentists "to effectively educate and counsel their patients about proper nutrition and oral health."1 According to the Commission on Dental Accreditation's Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs, effective January 1, 2000, graduates must be competent in providing the dental hygiene process of care. This includes the implementation of health education, preventive and nutritional counseling, reevaluation, and continuing care.2,3 All dentists take at least one course containing nutrition information during their education. However, most dental professionals do not incorporate nutritional counseling as a service in their practices. The reasons most commonly given for not including nutrition counseling in the dental practice setting are: time constraints, questions concerning dental insurance coverage, greater prioritization placed on dental procedures, and last, but perhaps the most important, is inadequate knowledge of the importance of nutrition as it relates to the dental patient. Many patients also do not realize that the dentist and dental professionals are resources for nutrition information.4

Oral health practitioners, however, are in a unique position to provide nutritional screening, assessment, and basic counseling, which can promote oral health and encourage healthier lifestyles. And the benefits can directly affect treatment outcomes—poor dietary practices can increase the risk of developing dental caries, increase susceptibility to periodontal disease, and delay tissue healing. Behavior changes to modify these practices can be implemented by working with the patient to establish goals during regular oral healthcare visits. From a dental perspective, diet and nutrition may affect the development and progression of disease of the oral cavity, and oral infectious diseases, in turn, can affect nutritional status.

Dietary counseling in a dental practice can be as simplistic as emphasizing the importance of fluoride, encouraging the use of dental sealants, discussing the frequency and types of foods eaten, and discussing the length of time that foods and beverages are retained in the mouth. Nutrition needs throughout the life cycle vary according to the age of the patient. It is often necessary to discuss with parents about establishing in their children good eating habits and oral hygiene skills at an early age. Baby bottle tooth decay/early childhood caries can result when infants are allowed to nurse continuously from a bottle of milk or from a mother's breast. Sugary drinks should be avoided during naps and throughout the night. Good nutrition and dietary practices should be discussed with women both before and after delivery. Adolescents are especially susceptible to oral disease because they can make more of their own food selections outside the home. Oral changes caused by diabetes, vitamin deficiencies, and hormonal irregularities are issues of concern among adult patients. Irregularities associated with these conditions can be determined and discussed after the oral exam at recare appointments.5

Comprehensive dental care includes consideration of the nutritional aspects of oral health and disease.6 Today's dental practitioner is not only concerned with educating patients for the prevention of caries and periodontal disease, but also involved in determining other potential health risks.7 Therefore, the focus needs to be on treating the whole person, not just the mouth. Recent research findings have pointed to possible associations between chronic oral infections and diabetes, heart and lung diseases, osteoporosis, stroke, and low-birth-weight infants.8-11 Although often overlooked, nutrition counseling can play an important role in the modern dental practice.12 By incorporating nutritional counseling as an integral component of regular dental checkups, dental practitioners can provide patients with an optimum level of care.

The impact of nutrition on dental education and clinical practice has created a greater awareness of the need for mainstream dentistry to form liaisons with other professionals in the health care delivery system.13 For patients with chronic health problems, the dental professional can provide referrals to health care providers who can offer specialized treatment. Extensive nutritional counseling must be referred to someone with the appropriate education and skills to provide guidance in this area. Thus, dietary counseling beyond the realm of dental practice must be referred to a medical doctor and/or a registered dietitian.

Learning About the Dietary Habits of Patients

Concern is growing about the food we eat and the "art" of staying in shape through regular physical exercise. Because of this, new diets draw media attention and many individuals react quickly to adopt them. Some individuals have psychological issues with weight (bulimic or anorexic patients) or have weight concerns because of a medical condition (eg, heart disease, AIDS, recovering cancer patient, etc). Any and all of these situations are part of the patient profiles seen in the dental office.

A method for collecting baseline patient dietary data should be developed and include:

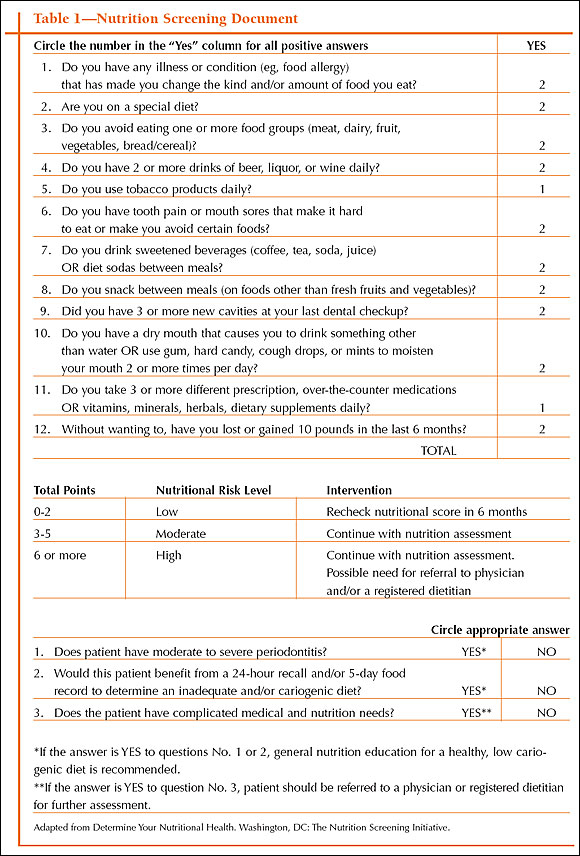

- a clinician-administered nutrition screening form completed with the patient by the office manager or the dental assistant (Table 1)

- a medical/psychosocial/dental history filled out by a new patient and updated at all subsequent appointments

- recorded findings from the intraoral/extraoral exam

Combined responses noted on these forms should be used to determine the patient's level of nutritional risk. A preplanned set of criteria should be established. Most screening tools have a cumulative score that aids in identifying those at nutritional risk.

Open-ended questions will provide further insight into a dental patient's nutritional habits. Patients should be asked to describe their eating patterns on a typical day. Eating frequency, variety in the diet, and missing food groups can be identified. General indications of nutritional inadequacy can be documented during a routine oral examination. The presence of intraoral/extraoral manifestations of malnutrition, rampant caries, a report of an unbalanced diet or high daily sugar intake, signs of an eating disorder, disorientation, extreme weight loss or gain since the last dental visit, or a critical medical condition all warrant further investigation of a patient's nutrition habits.

Additional tools are available to aid the dental professional during the dietary counseling process. Food diaries or a food frequency questionnaire can be used in the analysis of the patient's dietary intake. Careful observation, screening, and conversation with the patient will alert the dental professional to the nature and extent of nutritional counseling necessary. Adolescents; pregnant women; patients with rampant caries, periodontal disease, and edentulous conditions; oral surgery candidates; or oral cancer patients have specific dietary needs that must be considered before counseling. Based on the practice's established criteria, the dental professional must determine whether to provide nutrition services in the dental office or make appropriate referrals to a medical doctor or registered dietitian for further consultation. If the decision is made to counsel in the dental office, it is important to consider patients as individuals, to listen to what they say, and then help them to set goals that are reasonable and obtainable. Short follow-up visits should be scheduled for those patients who receive dietary counseling.4

Stages of Change

Providing clients with adequate knowledge alone will not help them make the changes necessary to adopt new healthful behaviors. Knowledge may empower, but it is the individual who actually controls change.14 Health care providers make a big mistake when they assume that knowledge alone will lead to a change in attitude that ultimately will lead to a new behavior.

Prochaska's Transtheoretical Model of Change14 acknowledges that all individuals do not translate knowledge into action at the same pace; rather our level of change occurs in stages. Individuals move through 5 stages of motivational readiness when adopting any new habit. It is helpful for both the clinician and the patient to understand the stages of readiness before attempting to make changes. Certain strategies can help people move through the different stages. Decisional balance is a component of the stages of change model and involves the discussion of possible barriers and benefits that the patient may have regarding a specific change.

Prochaska's 5 stages are:

1. Precontemplation

2. Contemplation

3. Preparation

4. Action

5. Maintenance

Change is a process. The degree of readiness or willingness to change is self-determined. As an individual moves through the stages, he or she is likely to move forward and backward. Every move is part of the learning process. It is important to create awareness among patients that moving backward after they have moved forward is not a sign of failure, but a sign that they are trying. There is an assumption that dietary habits are learned behaviors and that they can be unlearned and replaced with new behaviors. Increasing knowledge and awareness is important, but the actual change occurs through a patient's decision to do so. Health practitioners must be open to a variety of cultural values and beliefs, and regardless of the counseling style, the patient's unique needs must be the target.

Stages of Change 14,15 |

| Precontemplation: "I am not intending to change." |

| |

| Contemplation: "I am intending to change in the next 6 months." |

| |

| Preparation: "I am doing the new habit, but not consistently." |

| |

| Action: "I am doing the new habit regularly, but for less than 6 months." |

| |

| Maintenance: "I have maintained the new habit for more than 6 months." |

Providing Nutrition Education

Nutrition services provided in the dental practice should focus on educating the patient about the relationship between diet and dental health. Basic dietary information can be evaluated by comparing the patient's diet to the MyPyramid Food Guidance System (www.mypyramid.gov). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans can provide further guidance.16 Recommendations can then be made based on this information.

Providing nutrition information in a unique and innovative way can spark the patient's interest as opposed to simply being handed a brochure. A dental practice in Pacific Grove, California, developed what they called a nutrition nook. Foods high in sugar vs low-sugar alternatives were displayed. Informational brochures were located beneath the shelves. Comfortable seats were provided so that the patient could sit down and read through materials before the dental appointment.17 Another alternative involves audiovisual tapes, which can be viewed while the patient is seated in the dental chair.18 Food labels provide an excellent source of discussion of the fat and sugar content as well as the sodium content of the patient's commonly consumed foods, and are just one example of how the dental professional can create a "teaching moment."

Direct and Nondirect Counseling

The medical model is a commonly used direct approach to counseling. In this instance, the health professional assumes an authoritative role focused on the patient's dietary problem.19,20 The patient provides information about the diet, but otherwise remains passive. The health professional usually controls the session by giving detailed instructions. The advantage of the direct approach of counseling is that it usually requires little time, but it limits the chance of long-term success because the patient is not committed to dietary changes; he or she is merely listening to what is being said. However, the direct approach toward changing food behaviors may be necessary when a patient has a life-threatening condition, such as kidney failure.

When a health professional assumes the facilitator role, he or she makes things easier by providing appropriate sources of knowledge to achieve the patient's desired objectives.19 Facilitators give support and create a comfortable environment that encourages self-disclosure of personal issues. A facilitative approach encourages patient involvement so that the methods of change are designed according to the patient's individual goals and desires. This type of approach is nondirect with the patient actively participating.19,20 The health professional provides information on the etiology of dental disease, the diet, and the use of dietary assessment tools. The likelihood of success increases because the patient is actively involved in the process.

Setting Goals/Monitoring

Setting goals is an important step in the success of any counseling program. Certain principles of goal setting can improve a patient's chance of success21:

- Being specific

- Setting short-term goals to reach long-term goals

- Encouraging self-monitoring to track progress

It is important for the patient to develop specific and realistic goals. Encourage patients to create a plan that involves small, achievable goals. This will help them gain the self-confidence needed to continue working toward a long-term goal. The patients can identify those things that they feel are the most important about making the change, and discuss those things they perceive as barriers. Encourage the patient to develop a priority list, which should include those things that the patient would like to work on before the next meeting. Finally, have the patient self-monitor. By tracking progress, a patient will identify areas that are strengths and weaknesses. This will allow greater focus as they continue toward their long-term goal.

Establishing Personal Rewards

Making changes can be discouraging and frustrating, especially if expectations are not met immediately. To deal with this difficulty, patients should reward themselves throughout their process of change. Rewards can be set for both short-term and long-term goals. Rewards can be tangible, such as books, or tickets to a movie, concert, or sporting event. Rewards also can be intangible, such as praise, feeling happier, having more energy, or feeling more confident. Patients should learn how to reward themselves so that the discouraging moments are a little easier to handle. Self-monitoring is of key importance because it allows patients to notice when an improvement occurs. Also important is enlisting the support of others. Encourage patients to create support groups that will help keep them on track. Remind them that progress, not perfection, is what counts.

Providing Follow-up

The success of a dietary behavior change depends on the patient. Goals must be established and clearly understood. An evaluation of the patient's desire to change dietary habits can be done immediately following the dietary counseling session. Demonstrated interest and cooperation will indicate the patient's level of motivation. Future appointments should be set so that ongoing feedback and reevaluation can be provided. Although desirable, a short time between visits is probably not feasible. Instead, 3-month and 6-month reevaluation appointments should be established.

Before the 3-month recall, the patient could be sent information with directions for keeping a 3- to 7-day food record to be reviewed during the appointment. Plaque control procedures should be reviewed if the dietary concerns are related to an increase in caries rate. Also, the patient's eating habits should be reviewed and any needed suggestions should be made. Because the primary focus is on the types of foods the patient consumes that could affect dental health, particular emphasis should be placed on sticky foods, liquid sugar, and slowly dissolving sugar. However, it is also important to look at any lack of nutrients in the patient's diet, which could indicate a need for referral to a registered dietitian or medical doctor. Modifications of goals also may be necessary. Smaller goals may be needed to encourage the patient to stick with the plan. Progress should be documented in the chart. If needed, additional materials should be distributed and plans for continued change discussed.

A dietary follow-up can be incorporated as part of the regularly scheduled recall appointment. Updating the medical/dental history, extraoral/intraoral exam, dental charting, and periodontal charting will be necessary. Charting should be compared with recorded data from the previous recall appointment, whether 3-, 4-, or 6-month interval. Caries incidence and extraoral/intraoral changes that would denote nutritional concern should be noted. If caries continues to be a problem, a topical application of fluoride might be recommended. Finally, dietary recommendations should be made in accordance with information derived from the updated assessment. Progress should be documented, education should be provided, and a continued plan of action established. This evaluation process should continue until the desired behavior change has been accomplished. It is important to continually ask for feedback to make sure that the patient's needs are being met. Remember, success depends on learning by the patient and, to learn, the patient must be involved in the whole process. The patient will set the goals, and the healthcare provider will be the cheerleader who encourages achievement of those goals.

Conclusion

Nutritional counseling is an important aspect of the dental hygiene process of care, one that can be easily incorporated into the dental practice setting. It allows the dental professional to identify patients at nutritional risk and make appropriate recommendations or referrals. It is a value-added service that not only enhances a practice, but also provides the dental professional with an opportunity to make a difference in the lives of patients.

References

1. American Dental Association. Preventive Health Statement on Nutrition and Oral Health. 1996 Transactions: 682.

2. Commission on Dental Accreditation, American Dental Association. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs. Chicago, Ill: American Dental Association; 2000.

3. Sovereign CB. Dental hygiene's role in nutrition education. Contact Int. 1999;13:1-3.

4. Boyd LD, Dwyer JT, Palmer CA. Current Concepts for the Application of Nutrition in Oral Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Boston, Mass: Joint Project of Frances Stern Nutrition Center, Tufts University School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University School of Medicine, Dept of Preventive Dentistry and Dept of Continuing Education; 1998.

5. IFIC review: nutrition and oral health: making the connection. September 1998. International Food Information Council Foundation Web site. Available at: http: //ific.org/publications/reviews/oralhealthir.cfm. Accessed May 8, 2006.

6. Cutter CR. Oral health emphasis in dietetic internship programs. J Am Diet Assoc. 1986;86:84-85.

7. Palmer CA. Nutrition, diet and oral conditions. In: Harris NO, Garcia-Godoy F, eds. Primary Preventative Dentistry. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2003: 419-447.

8. Krall EA. Osteoporosis and the risk of tooth loss. Clin Calcium. 2006;16:63-66.

9. Miley DD, Terezhalmy GT. The patient with diabetes mellitus: etiology, epidemiology, principles of medical management, oral disease burden, and principles of dental management. Quintessence Int. 2005;36:779-795.

10. Lowry RJ, Maunder P, Steele JG, et al. Hearts and mouths: perceptions of oral hygiene by at-risk heart surgery patients. Br Dent J. 2005;199:449-451.

11. Khader YS, Ta'ani Q. Periodontal diseases and the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: a meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2005;76:161-165.

12. Elborn S, Karp WR. The dietitian as a member of the dental health care team. J Am Diet Assoc. 1987;87: 1062-1063.

13. Furlong A. Nutrition and dentistry. AGD Impact. Jul 1999;27:9-13.

14. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1982;19:276-288.

15. Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Inc; 1997: 60-84.

16. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. 6th ed. Hyattsville, Md: US Depts of Agriculture and Health and Human Services. Home and Garden Bulletin No. 232-CP.

17. Lackey HB. Developing a nutrition nook in a dental office. J Nutr Educ. 1976;8(1):34.

18. Robinson LG, Paulbitski A, Jones A, et al. Nutrition counseling and children's dental health. J Nutr Educ. 1976;8: 33.

19. Holli BB, Calabrese RJ. Group dynamics, leadership and facilitiation. In: Communication and Education Skills for Dietetics Professionals. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1998:181-198.

20. Holli BB, Calabrese RJ. Counseling. In: Communication and Education Skills for Dietetics Professionals. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1998:45-58.

21. Holli BB, Calabrese RJ. Motivation. In: Communication and Education Skills for Dietetics Professionals. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1998:121-135.