You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

The code of ethics of the American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) states that dental hygiene professionals should promote access to dental hygiene services for all, supporting justice and fairness in the distribution of healthcare resources.1 This same concept is reflected in the American Dental Assisting Association's policy, which states that their organization is committed to providing access to oral healthcare services for all individuals.2 In both statements, there is an important focus placed on all individuals which includes those from diverse backgrounds, experiences, and socio-economic levels. Students enrolled in dental assisting (DA) or dental hygiene (DH) programs work with diverse patients as they progress through the curriculum, including those currently living in poverty. The United States (U.S.) Census defines poverty using income thresholds, which vary by family size and composition;3 a family of four earning $24,849 or less a year is considered impoverished.3 In 2016, 40.6 million Americans were reported as living in poverty.3

DA and DH students in their second year are required to rotate through a wide range of community-based dental facilities during their course of study at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). Settings include local health department dental clinics, federally qualified health centers, correctional institutions, Veteran's Administration and community hospitals, local private practice dental offices, preschool, elementary, and middle schools, senior citizen centers, and assisted living or long-term care facilities. Through these rotation experiences, DA and DH students will likely work with and treat low-income patients and families. Discovering and implementing educational approaches to help students become cognizant of the economic challenges and hardships that low-income patients experience is an important step to helping them develop a clearer picture of how social factors influence patient health decisions.

Yang et al wrote that, given the rising number of U.S families living below the poverty level, health professional students need to develop and become aware of the barriers and stress factors faced by low-income patients.4 Health professional students need to be able to move beyond stereotypes and generalizations and examine the reasons why low-income patients may not be able to continue with treatment recommendations or complete a treatment plan. In addition, Noone et al emphasized the goal of learning activities related to poverty in health education is to help change perceptions from a negative categorization to a more positive understanding and perspective.5 Simulations have been shown to help learners acquire new knowledge, and to better understand conceptual relations and dynamics.6 Gaba defines simulation as a technique which replaces or amplifies real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive manner.6 Fanning et al demonstrated that adults learn best when they are actively engaged in the process, participate, play a role, and experience not only concrete events in a cognitive fashion, but also transactional events in an emotional fashion. Learners must be able to make sense of the events experienced in terms of their own world. The combination of an active experience, particularly when accompanied by intense emotions, may result in long-lasting learning.7

The Missouri Community Action Poverty Simulation (MCAPS) has been used across health profession disciplines for both undergraduate and graduate level students to help them understand poverty.4,5,8-10 Evidence suggests that participants who have completed a simulation using MCAPS demonstrated changes in their knowledge and attitudes regarding poverty, experienced heightened awareness of the realities of living in poverty, and were able to identify factors contributing to poverty.10-15 Using simulations to assist future health care providers in cultivating their ability to reason, tap into their emotional intelligence, and improve their skills has been shown to be an exceptional learning modality that can be used to facilitate change.

Dental assisting and second-year dental hygiene students attending the UNC Chapel Hill Adams School of Dentistry participated in a MCAPS exercise with the goal of providing the students with an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of poverty on health and health-related behaviors for low-income families. The aim of this replicated study8 was to determine whether DA and DH students' understanding of the daily challenges faced by families identified as low-income was changed as a result of a poverty simulation exercise (PSE) and whether they found the experience valuable.

Methods

This exploratory descriptive study was determined exempt from further review by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Office of Human Research Ethics (study #16- 2886). In January 2017, 34 second-year DH and 23 DA students were required to participate in a 3-hour Missouri Association for Community Action Poverty Simulation (CAPS) exercise. Using methodology replicated from a previous study,8 students participated in the simulation experience before beginning their mandatory 3-week practicums and weekly spring rotations.

The PSE was designed for participants to role-play the lives of low-income families ranging from single parents trying to care for their children to senior citizens trying to maintain their self-sufficiency on Social Security.16 The PSE experience included a registration process, simulation experience, and debriefing session. During the registration process, participants were randomly assigned their new identities and families (Figure 1). These identities were based on family profiles created by the Missouri Community Action Network (MCAN). Once assigned their roles, participants reported to their simulation homes labeled with their new family names. Homes were set up in the center of the room surrounded by resource centers (Figure 2). At each home site, families received a packet of information, providing background information on each family member's responsibilities and expectations. The packet also included identification documents, specific items the family needed to keep in their possession, money for various costs including bills that needed to be paid, and transportation passes to move from resource to resource throughout the exercise.

The PSE was facilitated by 4 MCAN trained facilitators, with the primary facilitator acting as the town mayor. The remaining co-facilitators assisted with the resource centers and answered any questions participants had throughout the experience. The primary facilitator provided instructions, ground rules, defined terms, and allowed for the family units to open and read through their packets before the start of the simulation. Community resources, which the families needed to utilize in order to meet the objectives of the PSE, were also introduced and described prior to starting the simulation. Resources included for profit, nonprofit and governmental organizations. PSE resource units included the social service office, mortgage/rent collector, supercenter (Food-o-rama), employment agency and interfaith services. The PSE occurred over one hour of time. For the purpose of the simulation the time was divided into four 15-minute weeks and three 3-minute weekends, representing one month in the life of the family. During the 15-minute weeks, the main goal was to provide the necessities of their family and maintain shelter.16 Participants had to make sure they attended work or school, paid bills, provided childcare for children, and had some form of transportation. The 3-minute weekend allowed the resource centers the opportunity to regroup and gave families a moment to discuss steps to take for the upcoming week.

A debriefing session took place immediately following the PSE. Facilitators asked the DH and DA students reflective questions regarding the PSE. Questions used to guide discussion included asking how participants felt about the issues they encountered and whether they discovered any emotions and attitudes regarding the challenges and barriers faced by low-income families as a result of the simulation. The debrief session allowed the group the opportunity to express their feelings and build off each other's answers during the open discussion. Following the debrief session, a support specialist familiar with the PSE read a verbal consent script to the participants to complete the paper survey. Participants were informed that the completion of the survey implied consent and that participation was entirely voluntary. The survey instrument was identical to one used in two previous studies that sought to evaluate the impact of a PSE on student understanding4,8 and consisted of eight items. Five statements asked the participants to focus on their level of understanding of low-income patient challenges prior to and following the simulation. Each before and after item was rated on a scale of 1 (no understanding) to 5 (almost complete understanding). Participants were also asked to rate the value of the simulation exercise on a scale of 1 (no value) to 10 (extremely valuable) in preparing them to understand the challenges faced by patients who have limited incomes/resources during their rotation. The final two questions were open-ended; "In your opinion, what do you think was the best part of the activity?" and "Please list any suggestions you have to improve this activity." Surveys were returned to an unmonitored drop box in the same room as the PSE.

Participants received a second survey following their community practicum and rotations in April 2017. Data was collected for the DH and DA groups separately due to differing schedules. The same support specialist read the verbal consent script to participants. Following the verbal consent, the post-rotation survey consisting of the same five items regarding understanding levels of low-income populations was delivered. Participants were asked to reflect using a scale of 1 (no understanding) to 5 (almost complete understanding) on their level of understanding of the challenges facing low-income patients following their practicum and/or community rotation experiences. Participants returned their surveys to an unmonitored drop box. Descriptive statistics were calculated and summarized using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS®, Armonk, NY) software.

Results

Fifty-seven DH and DA students participated in the PSE. Following the simulation and debrief, 55 students completed the survey (n=55) for a response rate of 96%. Three months following the PSE and upon completion of all community rotations, 55 students completed the second survey (n=55) for a response rate of 96%. Incomplete surveys were received from several participants during the first and second survey; questions that the individuals responded to were included in the analysis. Findings from the post-simulation survey showed that 40% (n=22) of participants believed or thought they had a moderate to complete understanding of the financial pressures faced by low-income families prior to participating in the PSE. Responses to the follow-up question regarding the participants level of understanding the financial pressures of this population as a result of the PSE indicated that the majority of the participants (91%, n=49) felt they had a moderate to complete understanding of their financial stress. Statements reported in the open-ended portion of the survey provided insight regarding participants feelings about the experience. One respondent reported that the PSE provided the ability "to see how much stress income puts on families." Another respondent wrote how the PSE allowed them "to see how the parents of low-income families worked to keep their head above water, to keep life going."

Following the simulation, a majority (87%, n=48) felt they had a moderate to complete understanding of difficult choices people with low resources must make each month when stretching limited income. In reflecting on their level of understanding regarding the difficulties in improving one's situation and becoming more self-sufficient on a limited income prior to the PSE, less than half (42%, n=23) thought they had little to no understanding following the PSE, while 100% (n=55) of respondents felt they had a moderate to complete understanding.

Positive increases were also identified when looking at levels of understanding in relationship to emotional stressors and frustrations created due to lack of resources. Prior to the simulation, 67% (n=37) of respondents thought they had a moderate to complete understanding. However, post simulation 98% (n=53) indicated a moderate to complete understanding (Table 1). One participant wrote, "Although poverty can't be replicated for real, this showed some of the stress that it can put on someone." Another stated, "The actual act of going through the day and life in poverty, made you realize the challenges. I knew they existed but didn't realize how limiting they were."

A majority of the respondents (89%, n=47) felt the PSE was moderately to extremely valuable in preparing them to understand the challenges faced by the patients with limited incomes that they would likely see in future practicum experiences and rotations. Only 6% (n=3) felt neutral towards how the PSE had prepared them and 6% (n=3) responded that the PSE had little to no value in preparing them to care for future patients living in poverty. When looking at the sum of respondent's perceptions before and after the PSE, the overall impact of the experience showed a positive increase in understanding by an average of 5 units.

Three months after completing the PSE, and after completing their community practicum and rotations, students completed a second questionnaire. There were slight increases in the levels of understanding of the financial challenges of poverty (Figure 3). A majority (85%, n=47) of participants indicated encountering families living in situations similar to those portrayed during the PSE. Of those surveyed, 89% (n=48) reported that during the practicums or community rotations they gained a moderate to complete understanding of the effects of poverty on the oral health status of low-income families, while 11% (n=6) revealed having little to no understanding. When asked about the effect of the simulation exercises' ability to increase their level of empathy towards the low-income patients served during their practicum or rotations, over three-fourths (80%, n=44) felt that they became moderately to completely empathetic.

The PSE also had a positive effect on (81%, n=44) participants' ability to be less judgmental toward the low-income patients served during their practicum or community rotations. Over three fourths of the participants (76%, n=41) found the PSE to be valuable in helping to prepare and understand the challenges faced by patients with limited incomes/resources encountered during their practicums or rotations. One respondent wrote, "It was a wonderful way of understanding how people strive to live in day to day life. It was overall an eye opener for people who do not experience these things."

Regarding the value of the PSE in relationship to practicums and community rotations suggest that participants who may have experienced poverty themselves felt that some participants did not take the PSE seriously. One participant wrote, "This isn't new to me, my mother raised 3 kids on her own while my dad was on drugs. It was nice to see others come and try to see how people in poverty live/grew up. But I felt others thought it was a waste of time. Some laughed and did not take it seriously." Another wrote, "I feel that my own experiences as a member of a low-income family helps me understand others. I felt that some students, who perhaps do not share these experiences, took the simulation as a game." In contrast another respondent wrote, "The simulation was very valuable for me. It opened my eyes to the struggle people face trying to improve their socioeconomic status. It's not as simple as I once thought." An additional comment stated, "I think it was very helpful to have the simulation because during rotations we will see certain situations and will know how to approach them." (Table 2)

Discussion

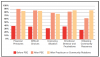

The purpose of this study was to increase DH and DA students' understanding of the daily challenges faced by families living with low incomes. Results confirmed that the participants' level of understanding changed substantially in all categories following the PSE (Figure 3). When comparing results from this study to a previous study focusing on dental students, a similar percentage of students in both studies reported that the PSE was moderately to very valuable8 (Figure 4). Participants in both studies displayed an increased understanding of the financial pressures, difficult choices, difficulty in improving one's situation, emotional stressors and the impact of community resources experienced by low-income families.

Unlike previous studies, this study included a second evaluation of the PSE after students returned from their community rotations, two months following the initial poverty simulation. Results suggest the knowledge and impact gained from the initial PSE continued to influence the participants far beyond the day of the simulation and levels of understanding remained high or increased in some categories.

Several other studies with a focus on the use of simulation to teach about poverty were noted as being effective in causing significant changes in knowledge and attitudes in relation to poverty.11-14,17 Disciplines affected by these simulation studies included nursing, social sciences, health and human services, as well as others.11 It is noteworthy that these studies also used the same MCAPS kit utilized in this study and increases in participant knowledge and attitudes in several categories are similar to findings previously cited in the literature.

Findings from this study capture the goal of simulation when improving practice as described by Zigmont et al. In simulation, the learner moves from comprehension, to application, and analysis; bringing all aspects of the experience together.18 Allied dental health students and practicing clinicians taking part in simulations such as the MCAPS should be able to take their learning to a higher level. Through the PSE, participants learn not only based on the exposure received from working within their roles and family problems that arise in the "simulated world" but they are also able to transfer their feelings and use the knowledge and empathy gained to help them work through real life clinical situations. In the Zigmont et al study, it was also found that learner competencies in analytical and knowledge application were more evident following simulation experiences.18

Oral health disparities continue to persist in the U.S. Both the dental hygiene and dental assisting professions can act as key stakeholders in helping to close the gaps that still exist. Incorporating immersive simulation exercises that initiate change in attitudes, and increase awareness on issues, can be beneficial additions to the DH and DA curriculum. Increased understanding of struggling families unable to afford the basics of life can influence healthcare providers' perceptions and decisions when providing care.

Limitations of this study include not identifying within the questionnaire any mixed experiences with poverty brought to the experience by the participants. Several of the students grew up in poverty and knew the challenges people face. Another limitation of the study is that the PSE lasted only one hour. Subsequent discussions on socio-economic status and its impact of dental care may help to increase understanding and change perceptions following the simulation. Future research should focus on how simulation experiences focusing on poverty also connect with greater understanding of diversity/inclusion and levels of cultural competency. Incorporating questions on cultural competency during the debrief section of the PSE to stimulate discussion could demonstrate the need for additional cultural competency training or activities.

Conclusion

Results from this study demonstrated that a PSE was effective in eliciting change in allied dental health students' affective perceptions regarding poverty and raised their understanding of challenges faced by low-income populations. Understanding the impact and barriers impoverished families and individuals face is of importance for all dental health providers across all settings.

About the Authors

Lattice D. Sams, RDH, MS is an associate professor and Assistant Director of the Dental Hygiene Programs in the Division of Comprehensive Oral Health, Adams School of Dentistry; Lewis N. Lampiris, DDS, MPH is Assistant Dean for Community Engagement and Outreach, Division of Pediatric and Public Health, Adams School of Dentistry; Tiffanie White, RDH, MS is an assistant professor in the Division of Comprehensive Oral Health, Adams School of Dentistry; Alex White, DDS, DrPH is an associate professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health; all at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

Corresponding author: Lattice D. Sams, RDH, MS; lattice_sams@unc.edu

References

1. American Dental Hygienists' Association. Bylaws and code of ethics. [Internet]. Chicago, IL: American Dental Hygienists' Association [updated 2018 Jun 25; cited 2019 March 1]. Available from: https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/7611_Bylaws_and_Code_of_Ethics.pdf

2. American Dental Assistants' Association. Manual of policies and resolutions. [Internet]. Bloomindale, IL: American Dental Assistants' Association [updated 2016 March; cited 2019 March 1]. Available from: https://www.adaausa.org/about-adaa/policies-and-resolutions.

3. Proctor BD, Semega JL, Kollar MA. Income and poverty in the United States: 2016. US Census Bureau current population reports [Internet]. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2017 [cited 2019 March 1]; Available from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/demo/P60-259.pdf

4. Yang K, Woomer GR, Agbemenu K, Williams L. Relate better and judge less: poverty simulation promoting culturally competent care in community health nursing. Nurse Educ Pract; 2014 Nov; 14 (6): 680-5.

5. Noone J, Sideras S, Gubrud-Howe P, et al. Influence of a poverty simulation on nursing student attitudes toward poverty. J Nurs Educ 2012 Nov; 51(11):617-22.

6. Gaba, D. The future vision of simulation in health care. BMJ Qual Saf Health Care 2004 Oct;13 (suppl 1) i2-i10.

7. Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Health. 2007 Jul; 2(2):115-25.

8. Lampiris LN, White A, Sams LD, et. al. Enhancing dental students' understanding of poverty through simulation. J Dent Educ. 2017 Sep; 81(9):1053-61.

9. Clarke C, Sedlacek RK, Watson SB. Impact of a stimulation exercise on pharmacy student attitude toward poverty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016 Mar 25; 80(2):21

10. Turk MT, Colbert AM. Using simulation to help beginning nursing students learn about the experience of poverty: A descriptive study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018 Dec; 71:174-9.

11. Reid CA, Evanson TA. Using simulation to teach about poverty in nursing education: a review of available tools. J Prof Nurs. 2016 Mar-Apr; 32(2):130-40.

12. Nickols S. Y., Nielsen R.B. Developing social empathy through a poverty stimulation. J Poverty. 2011 Jan; 15: 22-42.

13. Patterson N, Hulton LJ. Enhancing nursing students' understanding of poverty through simulation. Public Health Nurs. 2012 Mar-Apr; 29(2):143-51.

14. Steck, LW, Engler JN, Ligon M, et al. Doing poverty: learning outcomes among students participating in the community action poverty stimulation program. Teach Sociol 2011Jul; 39: 259-73.

15. Strasser S, Smith MO, Denny DP, et. al. A poverty stimulation to inform public health practice. J Health Educ 2014 Sep; 44: 259-64.

16. Missouri Community Action Network. Poverty

simulations. [Internet]. Jefferson City, MO Missouri Community Action Network; [cited 2019 March 1]. Available from: http://www.communityaction.org/povertysimulations/.

17. Todd M, de Guzman MR, Zhang X. Using poverty stimulation for college students: a mixed-methods evaluation. J Youth Dev 2011Jun; 6: 75-9.

18. Zigmont, JJ, Kappus, LJ, Sudikoff, SN. Theoretical foundations of learning through simulation. Semin Perinatol 2011 Apr; 35(2): 47-51