You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

The ADAA has an obligation to disseminate knowledge in the field of dentistry. Sponsorship of a continuing education program by the ADAA does not necessarily imply endorsement of a particular philosophy, product, or technique.

In recent years, the stage has been set for all oral healthcare professionals to become actively involved as facilitators and leaders in tobacco dependence education and control efforts. One goal of Healthy People 2020 is to increase the proportion of adults who received information from a dentist or dental hygienist focusing on reducing tobacco use or on smoking cessation.1

In this millennium, we expect an ever-increasing number of dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants to participate in clinical and community interventions that focus on both tobacco prevention and cessation strategies. Although upwards of 90% of dental providers have reported that they routinely ask patients about tobacco use, only 50-76% counsel patients, and less than half routinely offer cessation assistance such as self-help materials, referral to cessation counseling or a prescription for pharmacotherapy.2-4 Many lack confidence in providing cessation advice.5-7 The fact is, helping dental patients to quit using tobacco can be practically accomplished in clinical settings by oral healthcare professionals. More than twenty years of accumulated evidence has shown the efficacy of this approach. Oral healthcare providers are able to offer this service with few interruptions in their daily routine.8-10 Additionally, many patients who are helped respond with gratitude and loyalty.

Oral healthcare professionals and other health care workers have an ethical obligation to inform patients about the hazards of tobacco use and to encourage tobacco users to stop. Additionally, the oral healthcare team needs to praise and support those patients (especially impressionable young people who have never used tobacco in any form). Currently, 14% of U.S. adults aged 18 and above are smokers11and 3.4% are smokeless tobacco users.12 About 480,000 tobacco-related premature deaths occur each year in the United States.11 However, nearly 70% of adult smokers desire to quit and U.S. adult smoking rate has decreased substantially from its peak of nearly 45% in the mid-1960s.13 Nonetheless, approximately 34 million adults continue to smoke and oral health professionals can be effective in motivating and assisting these individuals to quit tobacco.11,14

The purpose of this course is to alert professionals to the harmful effects of tobacco, both to oral and systemic health. The course is also designed to teach oral health professionals specific skills that they may utilize to help individuals become free of their nicotine addiction. A significant amount of the course material applies to both smoked and smokeless tobacco; however, a discussion of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) is also included. Additional information on smokeless tobacco is presented in the ADAA continuing educational course, "Understanding the Dangers and Health Consequences of Spit (Smokeless) Tobacco Use."15

Effects of Tobacco Use

Health Hazards of Tobacco Use

According to the numerous U.S. Surgeon General's Reports on Smoking and Health, issued since 1964, smoking has been causally linked to heart disease, vascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer of the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, lung, pancreas, and bladder. It is also implicated in the development of gastric ulcers, chronic obstructive lung disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, sinusitis, and other respiratory disorders. Pregnant women who smoke are more likely to have premature, low birth-weight infants or spontaneous abortions. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that nonsmokers who inhale the secondary side-stream smoke from tobacco products are also at greater risk for these conditions.13

Tobacco use is a pediatric concern. Children raised in homes where parents smoke are more prone to respiratory diseases and ear infections.13,16-18 They are also more likely to use tobacco than those who are raised in tobacco-free homes.19 Additionally, although limited, current evidence suggests a causal relationship between exposure to tobacco smoke and dental caries in children.13

Nearly 90% of adult smokers started smoking before the age of 18 years.16 In the United States, approximately 2000 children and adolescents try their first cigarette each with more than 200 each day going on to become regular daily smokers. Although the rate of cigarette smoking among kids and teens has declined in recent years, their use of other tobacco products such as electronic cigarettes and hookah has increased. Furthermore, many young people use multiple tobacco products which put them at higher risk for developing nicotine dependence and continued tobacco use. In 2017, 27.1% of high school students and roughly 7.2% of middle school students used some form of tobacco. E-cigarettes are the most popular form of tobacco product used by youth today.16,20

By the time they are high school seniors, 8.1% of adolescents smoke cigarettes daily, 5.9% use smokeless tobacco, and 20.8% are e-cigarette users.16,20 Young people experiment with or begin regular use of tobacco for a variety of reasons including the following: simple curiosity, social norms, mass media influences, biological and genetic factors, peer and social media influences, parental smoking, and weight control. Other influences and risk factors include: lower socioeconomic status, low self-esteem and academic achievement, lack of support and skills to resist tobacco influences, exposure to product advertising, accessibility to tobacco products and mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.2 Nicotine dependence, however, is established rapidly even among adolescents, sometimes as early as two weeks. Because of the importance of primary prevention in this population, the oral healthcare team should pay particular attention to delivering these messages. Specifically, because tobacco use often begins during preadolescence, dental professionals should routinely assess and intervene with this population.

Oral Effects of Tobacco Use on Oral Health

Tobacco's damaging effects to oral health are well documented and should be easy for members of the oral healthcare team to identify. All oral healthcare professionals should deliver personalized tobacco cessation messages to patients, especially when they learn that these individuals have adverse oral conditions that are linked to tobacco usage. Dentists, dental assistants and dental hygienists have access to "teachable moments" at chairside when they can explain to their patients the tobacco-related, oral ill-effects from which they are currently suffering.21-23

People who smoke are very likely to have bad breath (halitosis). The breath of cigar and pipe smokers is more offensive than that of cigarette smokers because of the intense odors that emanate from cigar and pipe tobaccos. Inhaled smoke can create lung odors which often results in halitosis; its severity is generally in direct proportion to the amount of tobacco routinely consumed and the duration of the usage.

A condition known as hairy tongue occurs when the solids and gases in tobacco prevent the tongue's surface cells from sloughing off normally. As a result, yellowish, white, brown or black papillae are formed. Resembling fur-like projections, they trap bacteria and food debris on the tongue's surface (Figure 1). This phenomenon also contributes to halitosis.21-23

Smokers have significantly more stains and calculus deposits on their teeth than nonsmokers. These discolorations may become heavy on teeth, dentures and restorations. Smoking also has a detrimental effect on gingival tissues. Conditions such as acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) are more common in smokers; additionally, other periodontal conditions are frequently seen in the mouths of tobacco users.21-23,25 Of patients with periodontal disease, roughly 64% are current smokers.26 Dental providers need to inform their patients that current scientific evidence has shown a causal relationship between smoking and periodontal disease.13 Furthermore, continued smoking is extremely detrimental to the success of periodontal therapy. With smokeless tobacco use, recession and irritation of the gingiva routinely occur adjacent to where the quid, or tobacco product, is held.21-23

Over 7,000 chemicals and gases in tobacco smoke as well as their by-products may irritate the oral cavity.27 Chemicals such as ammonia, aldehydes, arsenic, benzo(a)pyrene, volatile acids, hydrogen cyanide, ketones, lead, pesticides, hydrocarbons, and radioactive polonium may all be present in smoke and smokeless tobacco. Sinusitis is a potentially disabling condition that causes an acute or chronic inflammation of the tissues lining the maxillary and frontal sinus air spaces. It occurs about 75% more often among smokers than nonsmokers and may be related to the chemical make-up of tobacco smoke. Furthermore, exposure to second-hand smoke is also associated with about 40% of the sinusitis cases in nonsmokers.28,29

As a powerful vasoconstrictor, nicotine also reduces blood flow to many tissues. This drug action may lead to delayed wound healing following oral surgery. Additionally, the incidence of alveolar osteitis (dry socket) among smokers is more than four times greater than among nonsmokers. This condition can occur when negative oral pressure, created as smoke is drawn into the mouth, disrupts the bloods clot in the postoperative extraction socket.21-22

Leukoplakia is an oral white patch or plaque that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease (Figure 2). Considered a precancerous condition, it is often associated with tobacco use. Any intraoral white lesions of this nature should be considered malignant until ruled out by microscopic examination (biopsy). Some leukoplakia lesions will regress if tobacco use is discontinued.

Another condition commonly seen in smokers is nicotine stomatitis or "smokers palate." Here, the roof of the mouth becomes thickened and white, with elevated bumps, which look like areas of cobblestone, and form around the partially blocked openings of salivary gland ducts. This abnormality, most commonly seen in pipe and cigar smokers, often disappears when the smoker quits and rarely develops into cancer.21-23

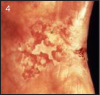

Epidermoid carcinoma (squamous cell carcinoma) is the most common oral cancer (Figure 3). Most typically seen in cigarette smokers, it is frequently found on the buccal mucosa or tongue. In addition, pipe smokers are more likely than other tobacco users to develop lip cancer. Erythroplakia, a red lesion, may also be associated with malignancy (Figure 4). Any red or white lesion, even those which are innocent looking, must have biopsies performed if they do not heal within a few weeks. Treatment of oral cancers may consist of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy or a combination of these approaches.21-23

Nicotine Addiction

Many U.S. Surgeon General's Reports have presented scientific evidence that cigarettes and other forms of tobacco are addictive.13 Numerous other studies on animals and humans have verified this report, showing that nicotine is the agent in tobacco that leads to addiction. A major conclusion of these documents is that the pharmacologic and behavioral processes that determine tobacco addiction are similar to those that determine addiction to other drugs, such as heroin and cocaine. Evidence of the addictive nature of nicotine has existed in the medical literature since the early 1900's, but the concept gained much greater acceptance and credibility with the release of these important government publications.13

Nicotine is found chiefly in the tobacco plant and all tobacco products contain significant amounts of nicotine. This drug is readily absorbed into the bloodstream from tobacco smoke, which enters the lungs, nicotine aerosolized through a vaping device (ENDS), or from smokeless tobacco, which is present in the mouth or nose. The blood levels of nicotine are relatively similar among subjects using different forms of tobacco. Once in the bloodstream, this powerful pharmacologic agent is rapidly distributed throughout the body in a variety of ways.30

Nicotine enters the brain within seven to ten seconds after inhalation. It interacts with specific receptors in brain tissue and initiates very diverse physiologic effects, which are quickly experienced by the user. Nicotine causes skeletal muscle relaxation and cardiovascular and hormonal alterations, including increased heart and breathing rates, blood vessel constriction (which raises blood pressure), and paradoxically, feelings of both stimulation and relaxation, depending on the circumstances under which it is used. Smokers may use tobacco to aid concentration, as an energy boost, or for its calming effects.30

Addiction

Addiction may be defined as an overwhelming compulsion to ingest a substance or engage in a process with increasing frequency and intensity, in order to experience its mind-altering effects and/or to avoid the pain of its withdrawal.30 As with many other addictive substances, users develop a tolerance to nicotine over a period of time; that is, they begin to require increasing amounts of nicotine in order to achieve the same effects.30,31

While human beings have no inborn need for tobacco, they often learn to use tobacco during childhood or adolescence. Initially, they may be influenced by role models, the mass media, and peers. Once they become accustomed to the effects of the nicotine and the socially rewarding aspects of tobacco use, their need to continue usage becomes strongly reinforced. At this point, both physiological and psychological factors begin to exert a powerful influence on them.30,31

Physical and Psychological Characteristics of Nicotine Addiction

The characteristics of nicotine addiction include:

• Stimulation - tobacco and nicotine help to organize thoughts and actions

• Handling - enjoyment in watching smoke and manipulating cigarettes, cigarette packages, matches, ashes, etc.

• Relaxation - nicotine has a tranquilizing effect especially after a meal or sexual activity, or during coffee or alcohol consumption

• Craving - "hunger" for nicotine when not using a form of tobacco

• Tension reduction - short-term stress relief caused by nicotine's overall effect(s) on the brain

• Habit - reinforcement of certain behaviors by associating them with pleasurable activities

Physiological dependency occurs when brain cells adapt so completely to a drug that they require it for "normal" functioning; when sudden drug abstinence occurs, signs and symptoms of withdrawal also occur. In nicotine dependency, nicotine craving is often the most predominant physiological symptom. Other withdrawal manifestations include irritability, restlessness, headache, drowsiness, gastrointestinal disturbances, reduced heart rate, sleep disturbances and impaired concentration, judgment, and psychomotor performance.30,31

Roughly half of all smokers attempt to quit each year, but less than 10% are successful in remaining smoke-free for more than one year.9 It has been suggested that in light of decades of declining smoking rates, those who still continue to smoke may be more resistant or "hardened" smokers.32-35 However, as the prevalence of smoking has declined, the proportion of heavy smokers (25+ cigarettes/day) has also decreased and constitutes less than 6% of the total smoking population.32 In Western industrialized nations, there is little evidence supporting the so-called hardening hypothesis, with the exception of two specific subgroups of smokers - women and those of low socioeconomic status. The high drive to smoke and regularity of smoking in individuals in these groups may make it more difficult for them to quit tobacco.32-35

Because the obstacles to stopping are great, it is important to offer sincere support to those who are motivated to quit tobacco. Many tobacco users try several times before they are successful. Rather than viewing their previous attempts as failures, tobacco users should be encouraged to credit themselves for achieving any degree of abstinence whatsoever. The most important message that can be relayed to these people is "Try, try again!" Additionally, by offering them self-help materials and informing them of available community tobacco dependence treatment programs, oral health professionals can actively help these persons to quit.36-39

One of the most positive sociocultural changes in recent years is the move toward smoke-free public buildings, restaurants and bars, transportation, and places of employment. This shift in our national attitude exerts additional pressure to give up tobacco. The public has become informed about the harmful effects produced by second hand smoke, also known as passive smoke or ETS (Environmental Tobacco Smoke). However, the increasing popularity and use of ENDS, particularly e-cigarettes, threatens to alter society's negative perception of smoking.

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS)

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) is an umbrella term for devices that are used to "vape" or inhale and exhale the aerosol or vapor that is generated during the use of noncombustible tobacco products (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes, e-cigs) represent a type of ENDS which have recently become a popular alternative to traditional cigarettes. Some e-cigarettes resemble regular cigarettes, cigars, or pipes, while others look like pens, USB sticks, and other ordinary items. The larger ENDS such as tank systems, or those modified by the user ("mods"), don't look like traditional tobacco products. A traditional e-cigarette kit includes a lithium battery, charger, power cord and nicotine cartridges; refill cartridges are purchased as needed. The cartridges come in many different flavors and nicotine strengths. One cartridge approximates a pack of cigarettes and the cost of using e-cigarettes is roughly half the cost of traditional cigarettes.40,41,42 E-cigarettes vaporize liquid from a cartridge containing nicotine, and a humectant such as propylene glycol, glycerin, and/or polyethylene glycol, flavorings, and other chemicals. Known as "vaping," the fine mist is then inhaled by the user. The vapor does not contain carbon monoxide or smoke but does consist of fine particles which contain various amounts of heavy metals such as lead, and toxic chemicals associated with cancer as well as heart and respiratory conditions.

Among U.S. young people, e-cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product. Compared to adults, kids and teens are more likely to use these products. In 2018, 4.9% of middle school students and 20.8% of high schoolers were current e-cigarette users. In contrast, in the prior year, current e-cigarette use by adult Americans was only 2.8%.

Overall, among adult e-cigarette users in 2015, 58.8% were also current regular cigarette smokers, that is dual tobacco users, while 29.8% were former smokers, and 11.4% had never smoked cigarettes. Of current e-cigarette users aged 45 and up, most were either current or former regular cigarette smokers, and less than 2% had never been cigarette smokers. Conversely, among young adults currently using e-cigarettes, 40% were never regular cigarette smokers.44

Electronic cigarettes are sold in stores and on the internet; they are marketed via the mass media, including television, movies, and various social media outlets. A recent study, for example, found that on YouTube, e-cigarettes are most often depicted in a positive light via non-traditional or covert advertisements featuring young people.45 The most common reasons cited by adults for using e-cigarettes are as a means to reduce or quit smoking, to reduce the costs of tobacco use, and to use a product perceived to be less toxic than conventional cigarettes.40,41 However, although limited, current research does not indicate that e-cigarettes are an effective aid in tobacco cessation.

Furthermore, although the body of literature on the health effects of e-cigarettes use is growing, because the products are still relatively new and evolving, research on the long-term health effects of these products is limited.41 However, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has reported that regular use of electronic cigarettes has resulted in minor systemic and oral adverse events such as headache, chest pain, cough, mouth irritation, sore throat, and dry mouth. More serious consequences of e-cig use have also been reported including pneumonia, congestive heart failure, seizure, rapid heart rate and burn injuries.41,46 Furthermore, a recent study noted that a chemical found in e-cigarette liquid, diacetyl, has been linked to severe respiratory disease.47 E-cigarettes can also be harmful to non-users; for example, the CDC has reported that from 2010 to 2014 the number of calls to poison centers involving nicotine-containing e-cigarette liquids has dramatically increased.48 Currently, ENDS including e-cigarettes are classified as tobacco products and are regulated by the FDA. However, while the FDA continues to mull regulations for the products, local communities and states have instituted additional restrictions on availability and sale of e-cigarettes.

Oral health care providers have an ethical obligation to advise patients and families on effective, evidence-based tobacco cessation methods. Therefore, in light of the lack of current research on the long-term effects of e-cigarettes, health care professionals should not recommend their use as a tobacco cessation aid over existing evidence-based therapies. For patients who are already using e-cigarettes to help quit smoking, the clinician should support their quit attempt, advise them to stop using conventional tobacco altogether, and then plan to set a quit date for e-cigarette use.41

Delivering the Tobacco-Free Message: Programs That Work

In 2008, an updated, 276 page Clinical Practice Guideline, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, was released by the Public Health Service.9 The Guideline, a comprehensive review of over 6,000 scientific articles, offers simple and effective interventions for all current and former tobacco using patients and recommends that "all patients should be asked if they use tobacco and should have their tobacco use status documented on a regular basis."9 For a copy, telephone 1-800-4-CANCER, or search the title at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/).

Findings and Recommendations

The key recommendations of the updated Guideline, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence,9 based on the literature review and expert panel opinion, are as follows:

1. Tobacco dependence is a chronic condition that often requires repeated intervention and multiple attempts to quit. Effective treatments exist, however, that can significantly increase rates of long-term abstinence.

2. It is essential that clinicians and health care delivery systems consistently identify and document tobacco use status and treat every tobacco user seen in a health care setting.

3. Tobacco dependence treatments are effective, across a broad range of populations. Clinicians should encourage every patient willing to make a quit attempt to use the counseling.

4. Brief tobacco dependence treatment is effective. Clinicians should offer every patient who uses tobacco at least the brief treatments shown to be effective in this Guideline.

5. Individual, group, and telephone counseling are effective, and their effectiveness increases with treatment intensity. Two components of counseling are especially effective, and clinicians should use these when counseling patients making a quit attempt:

• Practical counseling (problem solving/skills training)

• Social support delivered as part of treatment

6. Numerous effective medications are available for tobacco dependence and clinicians should encourage their use by all patients attempting to quit smoking - except when medically contraindicated or with specific populations for which there is insufficient evidence of effectiveness (i.e. pregnant women, smokeless tobacco users, light smokers, and adolescents).

• Seven first-line medications (5 nicotine and 2 non-nicotine) reliably increase long-term smoking abstinence rates:

o Bupropion SR

o Nicotine gum

o Nicotine inhaler

o Nicotine lozenge

o Nicotine nasal spray

o Nicotine patch

o Varenicline

-

• Clinicians also should consider the use of certain combinations of medications identified as effective in this Guideline.

7. Counseling and medication are effective when used by themselves for treating tobacco dependence. The combination of counseling and medication, however, is more effective than either alone. Thus, clinicians should encourage all individuals making a quit attempt to use both counseling and medication.

8. Telephone quitline counseling is effective with diverse populations and has broad reach. Therefore, both clinicians and health care delivery systems should ensure patient access to quitlines and promote quitline use.

9. If a tobacco user currently is unwilling to make a quit attempt, clinicians should use the motivational treatments shown in this guideline to be effective in increasing future quit attempts.

10. Tobacco dependence treatments are both clinically effective and highly cost-effective relative to interventions for other clinical disorders. Providing coverage for these treatments increases quit rates. Insurers and purchasers should ensure that all insurance plans include the counseling and medication identified as effective in this guideline as covered benefits.

The basic intervention techniques chosen for the above programs include the systematic use of a protocol known as the "Five A's." These are:

• ASK patients about their tobacco use at every appropriate opportunity. Identify and document tobacco use status for each patient.

• ADVISE all tobacco users to stop. In a clear, strong and personalized manner, urge every tobacco user to quit.

• ASSESS willingness to make a quit attempt. Determine the patient's readiness to make a change.

• ASSIST patients in stopping. Use counseling and pharmacotherapy to help a patient quit.

• ARRANGE for supportive follow-up procedures. Schedule a follow-up contact, preferably within the first week after the quit date.Tobacco Cessation Programs for the Dental Practice

It is realistic for most dental practices to incorporate tobacco education into existing office procedures (Table 1). Many patients will stop using tobacco if they receive cessation advice from a trusted health professional. By asking patients to complete the necessary cessation related forms while waiting in the reception area, the staff will need only a few appointment minutes to ask about tobacco use and offer advice accordingly. Additionally, when a lesion or any abnormality associated with tobacco use is found, the oral health professional has a unique and potent opportunity, a teachable moment, to present the tobacco-recovery message. Tobacco cessation can be mentioned in some manner at every dental visit, however brief the message may be. Repetition is often a key factor in success. Individual patients will need varying amounts of time. Some people will be self-starters, while others may need more guidance. For instance, they may need to gain insight into their personal strengths and support systems, which can help them through the cessation process, or they may need to create a group of individualized quitting strategies.36-39

By providing patients with a smoke-free professional environment, the dental office and other health care settings can exert a positive influence on tobacco users and those in the process of quitting. To establish credibility, a dental office "No Smoking" policy is essential. A prominent sign such as "Thank You for Not Smoking" should be displayed in the reception area. Free quit-smoking pamphlets and self-help material, published by the American Cancer Society, the state tobacco quitline (1-800-QUIT NOW), or American Lung Association, should also be available for interested patients to read and take home. Because tobacco advertising is very prevalent in popular magazines, those in charge of reception room reading material might consider displaying only those publications that do not include tobacco ads.36-38

The medical/dental health history must address tobacco use by asking patients to note whether they use tobacco, which forms of tobacco they use, how long they have taken the product(s), and how much they are consuming daily. After reviewing this information, the dental assistant can place an appropriate sticker or an alert in the electronic record of each patient who smokes to remind the staff to ask about tobacco usage at every appropriate opportunity.36-39,49

During the oral examination, the oral healthcare team can increase patient awareness by delivering a personalized message about tobacco use and relating it to any pertinent systemic health history finding or oral condition that has been noted. These findings might include chronic bronchitis, sinusitis, heart disease, emphysema, hypertension, respiratory disease, dental stains, calculus build-up, periodontal pocketing, or suspicious soft-tissue lesions, such as leukoplakia. A good time to recommend that a patient quit tobacco use is at the end of a dental procedure, when the person's mouth is clean and fresh. While some patients will appreciate this concern and be ready to act, others will resist. If the information is presented in a caring and nonjudgmental manner, usually the patient will not respond to it defensively, even those who are not ready to quit. The suggestions given and the patient's responses should be documented in the dental record. Accurate record keeping will remind the oral healthcare professional to ASK, ADVISE, and ASSESS effectively and appropriately during subsequent appointments.36-39,48,49

5R's Motivating a patient to quit smoking9

Relevance: Provide information that has the greatest impact on the patient's disease status, family, or social situation (e.g., children and second-hand smoke).

Risks: Acute risks-shortness of breath, exacerbation of asthma, harm to pregnancy, impotence, infertility, increased blood carbon monoxide, bacterial pneumonia, increased risk for surgery. Long-term risks-heart attacks, strokes, lung and other cancers, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, long-term disability and need for extended care. Environmental risks-increased risks of lung cancer and heart disease in spouses, higher rate of smoking by children of tobacco users, increased risk of low birth weight babies, SIDS, asthma, middle ear disease, and respiratory infections in children of smokers.

Rewards: Highlight benefits most relevant to the patient, such as better health, improved sense of taste and smell, money saved, good example for children, more physically fit, and reduced wrinkling and aging of skin.

Roadblocks: Ask the patient to identify barriers to quitting, such as withdrawal symptoms, fear of failure, weight gain, lack of support and depression. Note elements of cessation treatment, such as problem solving or pharmacotherapy.

Repetition: Repeat the motivational intervention each time the patient has an office visit. Let the patient know that most people make repeated attempts to quit before they are successful.

Without internal motivation, it is unlikely that an individual will stop using tobacco. If a patient's interest and motivation to quit are low, oral health professionals should simply state they are available to help whenever necessary. Health professionals should not badger patients to quit or display any judgmental or condescending attitudes when dealing with current or recovering tobacco users.36-39,49

Those who are highly motivated and ready to quit tobacco should be asked to select a quit date. While most who quit manage to accomplish this on their own, some may require assistance. At this point, patients and the oral health professional should discuss all available options. If the patient is interested in a formalized quitting procedure, s/he can be provided with a written list of telephone numbers, dates and locations of all reputable community programs and their fees. The American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, Seventh Day Adventists, Smoker Stoppers and numerous community-oriented quit smoking programs, such as State Health Departments and telephone quit lines are involved in effective cessation programs, which are offered free or at nominal cost. Smokers Anonymous support groups, based on the same principles as Alcoholics Anonymous, are active in many regions of the country and may be helpful to the would-be quitter, as well as to those who have already given up tobacco.36-39,49,50

For heavy smokers who are highly motivated to quit, nicotine reduction therapy is a viable option. This approach is based on the use of a nicotine-containing product. When nicotine-containing gum is chewed slowly it gradually releases nicotine directly into the bloodstream through the oral mucosa. It is designed to maintain blood levels that will help to offset withdrawal symptoms, which are a common cause of relapse during the first three months of smoking abstinence. The prescription for certain nicotine-containing medication can be obtained from the physician or dentist. It is important to use current prescribing guidelines and to carefully instruct patients on its proper usage.9,36-39,51

The American Dental Association (ADA) Guide to Dental Therapeutics (fifth edition)52 provides concise information related to the use of prescription and non-prescription medications used by dentists to help their patients quit using tobacco. It discusses all commercially available products covering their generic and brand names, indications for use, dosage ranges and interactions with other agents.52 The ADA is firmly behind the utilization of these products in clinical practice. Every dental practice should have this publication for office use. When dentists prescribe a tobacco cessation product, they are actually practicing preventive dentistry, promoting oral health and/or treating existing oral conditions.

According to the Public Health Service, at present, long-term smoking abstinence rates are currently and reliably being increased by seven first-line pharmacotherapies: Buproprion SR; varenicline; nicotine gum; nicotine inhaler; nicotine nasal spray and nicotine patch, and nicotine lozenge.9

Several days after the quit-smoking dates, dental office personnel can contact the patients who are using Nicotine Replacement Therapy and re-emphasize proper medication usage. At this time, it may be necessary to adjust dosages or review usage techniques. Conduct follow-up monitoring of the patient's progress at monthly intervals thereafter.52

While nicotine reduction therapy or the use of Zyban or Chantix are the only FDA approved clinically proven approach for smoking cessation available at this time, it is to be expected that the FDA will approve new pharmaceutic agents for the purposes of smoking cessation. Although their efficacy is not supported by research, the following methods have been used with varying degrees of success: hypnosis, acupuncture, laser therapy, aversion therapy (rapid smoking or smoking in an enclosed chamber), tapering (decreasing the number of cigarettes smoked over a period of time) and nicotine fading (e.g. using filtered brands to gradually reduce the amount of smoke inhaled). Switching to a lower tar or nicotine cigarette is not advisable as studies show that smokers who change to these brands usually will compensate for the nicotine loss by either inhaling more deeply, smoking more cigarettes, or taking more puffs. Presently, a wide array of over-the-counter self-help products are also being developed and marketed. However, most smokers can actually quit on their own when their motivation becomes strong enough.9,36-38,52

The oral healthcare team must work together to help their patients become smoke-free. But first, they must cooperate with one another. The ASSIST protocol can be applied to coworkers and patients alike. Dental assistants frequently have chair side time with patients and are in a unique position to show concern, empathy, and encouragement toward potential quitters. Those who are former smokers can serve as credible role models of success.36-38,49,50

Because of the traditional way in which dental appointments are scheduled, it is relatively easy to ARRANGE smoking cessation follow-up visits. A telephone call to a client on the designated quit day, notes in the office newsletter, and continual reassurance at subsequent appointments can all contribute to a patient's success. Fortunately, a great deal of the damage caused by tobacco use is reversible. Any positive changes in oral health (such as less stain and calculus on the teeth) can be noted during office visits.36-38,49,50

The Oral Healthcare Professional's Role in a Tobacco Cessation Program

Oral healthcare professionals can actively help patients to stop using tobacco by taking the following actions:

• Become nonsmoking role models. Encourage coworkers to become smoke-free, at least during working hours.

• Promote a smoke-free environment throughout the dental clinic. Provide patients with stop-smoking pamphlets and attractive smoking cessation displays. The American Lung Association, American Cancer Society, National Cancer Institute, state health department tobacco prevention and cessation area, and American Dental Association are all excellent resources for free or reasonably priced materials. Maintain an inventory of appropriate educational handouts.

• Make certain that medical/dental health history forms include questions which address tobacco use.

• Identify charts of all tobacco users with an appropriate sticker on the inside of the patient record, or an alert within the electronic dental record. Change to a "Quit Tobacco" sticker/alert when appropriate to reinforce and support the patient at each visit.

• Provide information about practice-based tobacco cessation efforts in the office newsletter (e.g., a list of healthy, sugar-free snacks, which those giving up tobacco may enjoy).

• Post or release via the newsletter an "I QUIT" list of patients in the practice (after obtaining their individual permission). This activity can serve as a practice-builder as well as a positive reinforcement to those who have been successful.

• Communicate to the whole oral healthcare team any relevant personal information that might positively or negatively influence the patient's ability to quit. Make notes in the patient's chart.

• Telephone potential quitters on or shortly after their designated quit day to see how they are doing. Answer any questions as needed. This can be done at the same time as appointments are being confirmed.

• Compliment those (especially young patients) who do not use tobacco in any form. Tobacco is considered a "gateway drug" for marijuana, since marijuana use is generally preceded by tobacco use. Individuals, particularly youth, can initially become addicted to nicotine through smokeless tobacco or ENDS use; as time passes, they frequently switch to traditional combustible tobacco products.

• Talk with tobacco-using patients about quitting and support those who have already stopped.Some health care professionals are concerned that if they approach their smoking patients with cessation advice, they will alienate or offend them. In reality, a vast majority of tobacco users would like to stop, but do not know how to do it. To relate to the smokers or recovering smokers in a supportive nonthreatening way, oral health professionals need to understand the general levels of quitting motivation, and their specific applications to individual patients.36-38,49,50

Stages of Change - What to Say

Prochaska and DiClemente53 have identified six stages through which people pass in attempting to stop using tobacco. As oral health professionals learn to meet individual patient needs, they should be aware of these various motivational levels of readiness for quitting smoking. The stages are as follows:

• Pre-contemplation: The person has not yet considered stopping.

• Contemplation: The person has thought about stopping but is not ready to act.

• Desire or Readiness: The person admits to sincerely wanting to quit.

• Action: The person is ready to attempt the quitting process, has selected a quit date and individualized strategies.

• Maintenance: The person is no longer using tobacco and is attempting to remain tobacco-free.

• Relapse: The person has returned to smoking one or more cigarettes daily, after stopping for a significant period of time.Suggested Dialogue

The following scenarios suggest possible dialogues which dental health professionals can have with patients, after assessing their motivational level or commitment to tobacco cessation.36-38,50,53

Pre-contemplation Stage

Question: "Have you thought about stopping smoking (or using smokeless tobacco or electronic cigarettes)?" If the answer is "no," express your concern about the patient's health, and help identify health advantages which would be gained by quitting. (Use information from the health history form.) Respect the patient's right to continue smoking. If they do not decide to quit, indicate that you will inquire again at future visits.

Contemplation Stage

Question: "Have you thought about stopping?" If the answer is "yes," assess past experience ("Have you ever quit before?") and discuss available recovery resources. "What has worked for you previously, in past attempts to stop?" Stress that most individuals make multiple attempts to quit, and the chances for success increase with each effort. "Would you be interested in accepting our help?" Oral health professionals should express the desire to help when patients are ready. Identify personal barriers (such as fears of weight gain and failure) and review all available resources that offer help (e.g., self-help materials, office counseling, group participation, and outside referrals.)

Desire/Readiness and Action Stages

Question: "Are you ready to set a quit date?" "Which strategies for stopping do you prefer?" At this level, the oral health team is preparing to negotiate a recovery plan with the patient. The patient should be asked to set a reasonable quit date (e.g., within one to four weeks in the future), and to consider a range of possible cessation strategies for personal use. Substitute activities for tobacco use (exercise, hobbies, etc.) can be explored if the patient shows interest or asks for help.

Maintenance Stage

Question: "How are you doing in your effort to stop smoking/quit tobacco?" "Is there something else we can do to help?" A follow-up telephone call can serve as a positive reinforcement to patients, offering them needed reassurance and support. Even when patients have not been successful, the staff should interpret quitting attempts positively and express empathy. If patients raise questions about coping skills or proper use of nicotine replacement products, address their concerns immediately.

Relapse Stage

Question: "Have you smoked (even taken a puff) in the past seven days?" If the answer is "yes," ask "What seemed to cause the SLIP ?" "Is there a way you might have avoided it?" Patients who have returned to smoking may benefit from learning to distinguish between a SLIP and a relapse. A SLIP involves for example, the occasional smoking of only a few cigarettes, while a relapse is characterized by a return to former levels of smoking, or in some cases, even higher levels. Stress to the patient that a slip can be viewed as "a slight lapse in progress." Reassure patients that relapses are common. The likelihood of permanent success increases with repeated attempts to stop.

Question: "Are you still interested in becoming tobacco-free?" Oral healthcare providers must continue to offer nonjudgmental, sympathetic support and encouragement to those who have relapsed; however, tobacco users must personally confront and "own" their habit, and choose to return to the action and maintenance steps of the quitting process.

As an oral healthcare professional, what do I say to patients about smoking/tobacco cessation? Many practitioners want to know what messages will have the most impact, and how they can be delivered in a meaningful and effective way. An effective cessation message focuses on the benefits of becoming a nonsmoker, rather than the detriments of continuing to smoke or use any form of tobacco. However, when responding to this perspective, some smokers for example, may rationalize that the damage caused by their smoking is already done. In keeping with a positive theme of hope, the practitioner can say:

• "It is never too late to quit smoking."

• "When you quit, most of the effects of smoking are reversible."

• Smoking cessation is the single most important step that you can take to enhance the length and quality of your life."

• "Your mouth will be a lot healthier and fresher when you quit smoking."

• "When you quit smoking, you will no longer be inhaling more than 4,000 harmful chemicals and gases."Make Your Message Relevant

It is critically important for the oral healthcare team to interact with patients who use tobacco, particularly combustible tobacco like cigarettes, and to carefully explain how their specific oral health problems are linked to their tobacco use behaviors. For example, during treatment, if a team member notes an oral condition related to tobacco use, not only can they discuss the problem with the patient, but also can encourage the patient to observe this condition by using a hand mirror. Additionally, the team member can assess the individual's readiness to set a quit date. Through discussion with the other oral healthcare team members and a review of well-documented notes (kept in the treatment record), the dentist can make a diagnosis and arrange for appropriate follow-up. As they gain experience in discussing tobacco issues with patients, oral healthcare professionals can become as comfortable with cessation issues as they are with details concerning periodontal pocket depths and plaque control.36-39

During subsequent appointments, as oral healthcare providers interact with their patients who use tobacco products, they can relay the following messages:

• "As your dentist (dental assistant or dental hygienist), I must advise you to stop tobacco use now."

• "Have you ever thought about quitting? Have you ever tried to stop before?" If so, "What happened?"

• "Did you know that you have periodontal disease? Quitting smoking would really help to slow down the rate of gum disease that is developing in your mouth."

• "You need to have gum surgery, but you will not heal properly unless you quit smoking."

• "Smoking is a common cause of bad breath. You may be able to solve this problem completely if you quit using cigarettes."

• "How about choosing a quit date within the next few weeks, now that you have decided to stop smoking?"Fear of Weight Gain

The fear of weight gain discourages many smokers (especially women) from trying to quit. Weight issues should be acknowledged and dealt with openly.9,36-38 The following responses may help to diffuse weight issues:

• "Did you know that as many as a third of people who quit smoking do not gain any weight? And those who do generally gain only 5 to 9 pounds."

• "The health risks that you are taking by smoking are far greater than the risk of nominal weight gain."

• "If you exercise regularly, you can ease withdrawal symptoms and counteract weight gain."

• "Now that you have given up smoking and want to eat more often, you need to avoid high-calorie snacks. Many of the foods that are good for oral health will also help you to avoid weight gain. Be careful about substituting high sugar items like gum or breath mints for tobacco."Encourage individuals with weight gain concerns to closely monitor their calories, sugar, and fat intake and to increase their activity levels. Regular exercise not only speeds metabolism, tones muscles, improves cardiovascular function, reduces tension, and burns calories; it also stimulates the release of endorphins, which can positively affect mood and disposition.9

While general health gains resulting from smoking cessation are well documented and dramatic, the psychological benefits associated with quitting are equally valid and impressive. Compared with current smokers, former smokers have a greater sense of self-efficacy, freedom, and control over their personal circumstances.9,36-38

The following supportive comments may motivate the patient who smokes to make a commitment to cessation:

• "It sounds to me as if you would like to regain control of your life again by quitting smoking. That's a worthy goal!"

• "Just think of all the freedom you'll have when you quit! Every cigarette that you do not smoke represents a bit of freedom that you have gained."These encouraging statements can be offered to patients from a health professional who is a former smoker/tobacco user:

• "Although this has been one of the most difficult tasks that I have ever accomplished as an adult, it is one of the most satisfying things I have ever done."

• "More than 3 million Americans quit every year. In fact, there are now over 50 million of us who are ex-smokers. I can tell you from personal experience that it can be done. Why not give it a try? I will be here to support you."This empathic response can be given to tobacco users who tried to quit, but did not achieve cessation:

• "I really respect the fact that you gave quitting a good try. Not everyone succeeds on their first try, but many people are able to quit after making several attempts. Why not try again?"

The Cost of Smoking

Although very few people quit smoking to save money, they are quite surprised to discover the actual cost of their tobacco use. The following comments are examples of how a health professional might motivate a resistant smoker to a state of cessation readiness:

• "Do you realize that, as a pack-a-day smoker ($5.97 per pack multiplied by 365 days), you are spending over $2,180 a year on your addiction?"

• "When you smoke, you pay three times- first, with your money; second, with your health; and third, with more money as you try to regain your health."

• "When you quit smoking, why not set aside the money that you would have spent on cigarettes, and on your first anniversary as a nonsmoker, reward yourself with a special purchase?"Summary

The oral healthcare team can use their professional knowledge and skills to lead smoking patients toward recovery; additionally, they can display candor, sensitivity and empathy in helping these individuals to make this positive choice. As they work together cooperatively within these parameters, the entire team's efforts will be wisely invested.

Glossary

Addiction - an overwhelming compulsion to ingest a substance or engage in a process with increasing frequency and intensity in order to experience its mind-altering effects and/or to avoid the pain of its withdrawal.

Bupropion (Zyban™) - a non-nicotine prescription pill used to reduce tobacco cravings and withdrawal symptoms.

Craving - an intense and often prolonged desire, yearning, "hunger" or appetite for foods or substances.

Dependency, physiological - the physiological reliance upon a drug or substance, resulting in specific body cell alterations; a condition in which continued usage becomes necessary to maintain the body's state of normalcy and balance.

Dependency, psychological - an emotional reliance on addictive substances and/or ritualistic behaviors.

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) - a form of noncombustible tobacco; includes a variety of products including vapes, vaporizers, vape pens, hookah pens, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes or e-cigs).

Erythroplakia - a particularly dangerous form of oral cancer which appears as a red, velvety-appearing patch.

Habit - a highly automatic behavior intensively learned and practiced over a prolonged period of time.

Leukoplakia - a white intraoral patch related to all forms of tobacco usage and considered to be precancerous.

Malignant - cancerous, and therefore potentially life-threatening.

Nicotine - the principle alkaloid of tobacco and its addictive agent.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy ("NRT") - an effective smoking cessation strategy which utilizes nicotine-containing delivery devices (nicotine gum, inhaler, nasal spray, patch, or lozenge) which helps to reduce and control nicotine cravings and withdrawal symptoms; generally administered for a 3 to 6 month period, while the addictive, psychological, and sociocultural aspects of cigarette smoking are simultaneously being addressed and overcome.

Relapse - the reactivation of addictive behavior after abstinence has been achieved and maintained for a significant period of time.

Second Hand Smoke or Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) - smoke that comes from the burning of a tobacco product or exhaled by smokers. Inhaling ETS is called involuntary or passive smoking.

SLIP - a temporary, minor reversal to former addictive practices; of lesser intensity and duration than a relapse; Also called: "A Slight Lapse In Progress."

Sobriety - complete abstinence from cigarette smoking; a term used by Smokers Anonymous.

Smokers Anonymous - a self-help program adapted for smoking cessation and based on the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Tolerance - a state which requires increasing amounts of the addictive drug to achieve the same effects.

Vaping - the act of inhaling and exhaling the aerosol, referred to as vapor, which is produced by an e-cigarette or similar device.

Varenicline - also known as Chantix™in America, or Champix™in Europe; a non-nicotine prescription medicine that comes in pill form.

Vasoconstriction - a narrowing or constriction of blood vessels.

Withdrawal syndrome - predictable signs and symptoms caused by altered central nervous system activity and appearing after a routinely received drug dosage is discontinued or rapidly decreased.

Questions and Answers

1. Is there an up-to-date list of tobacco-use control and cessation web sites?

Yes. Refer to these sites:

The CDC website - http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/quit_smoking/how_to_quit/index.htm

Top 4 Quit Smoking Websites - http://copd.about.com/od/quittingsmoking/tp/Quit-Smoking-Websites.htm

The American Dental Association (ADA) - http://www.ada.org/2615.aspx

The Office of the Surgeon General - https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/tobacco/index.html

2. Where can I get authoritative information relating to tobacco that can be used at chairside?

The American Dental Association Annual Catalog has a number of current pamphlets, posters and videos relating to the ill-effects produced by smoke and smokeless tobacco. Some are even available in Spanish. This catalog is available to ADA members at 1-800-947-4746.

For useful information, call The American Dental Association's Council on Access, Prevention and InterProfessional Relations (312-440-2860). Also contact the National Institute of Dental and CranioFacial Research's Oral Health Information Clearing House (1-866-232-4528).

The following website has materials that can be obtained to use for educational purposes: http://smokefree.gov/free-resources

Check with the local dental society for continuing education courses that would help train the oral healthcare team in smoking cessation programs.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. http://www.healthypeople.gov/ Accessed May 5, 2019.

2. Jannat-Khah DP, McNeely J, Pereyra MR, et al: Dentists' self-perceived role in offering tobacco cessation services: results from a nationally representative survey, United States, 2010-2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014 Nov 6;11:E196. doi: 10.5888/ pcd11.140186

3. Hu S., Pallonen U., McAlister AL. Knowing How to Help Tobacco Users. Journal of the American Dental Association. 137(2):170-179, February 2006.

4. Agaku IT, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Vardavas CI.A comparison of cessation counseling received by current smokers at US dentist and physician offices during 2010-2011. Am J Public Health. 2014 Aug;104(8):e67-75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302049. Epub 2014 June 12.

5. Albert DA, Severson H, Gordon J, Ward A, Andrews J, Sadowsky D. Tobacco attitudes, practices, and behaviors: a survey of dentists participating in managed care. Nicotine Tob Res 2005;7(Suppl 1): S9-18. 6.

6. Prakash P, Belek MG, Grimes B, Silverstein S, Meckstroth R, Heckman B, et al. Dentists' attitudes, behaviors, and barriers related to tobacco-use cessation in the dental setting. J Public Health Dent 2013;73(2):94-102.

7. Patel AM; Blanchard SB; Christen AG; Bandy RW; Romito LM. A survey of United States periodontists' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to tobacco-cessation interventions. Journal of Periodontology. 82(3):367-76, 2011 Mar

8. Romito L, Budyn C, Oklak, M, Gotlib J, Eckert J. Tobacco use patterns and relationship to disease risk in two dental clinic populations and assessment of a targeted intervention. General Dentistry. Sep/Oct 2012;60(5):326-333.

9. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. May 2008.

10. Warnakulasuriya, S. Effectiveness of Tobacco Counseling in the Dental Office. Journal of Dental Education. 66(9):1079-1087; 2002

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/. Accessed May 1, 2019

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use. Smokeless Tobacco Use in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/smokeless/use_us/. Accessed May 1, 2019.

13. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014

14. Carr AB, Ebbert J. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 June 13;6:CD005084. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005084.pub3.

15. Morgan S, et al. Understanding the Dangers and Health Consequences of Spit (Smokeless) Tobacco Use. CDEWorld.com. https://adaa.cdeworld.com/courses/21335-Understanding_the_Dangers_and_Health_Consequences_of_Spit-Smokeless-Tobacco_Use

16. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012.

17. Snodgrass AM, Tan PT, Soh SE, Goh A, Shek LP, van Bever HP, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Chong YS, Saw SM, Kwek K, Teoh OH; GUSTO Study Group Tobacco smoke exposure and respiratory morbidity in young children. Tob Control. 2015 Oct 26. pii: tobaccocontrol-2015-052383. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052383.

18. Amani S, Yarmohammadi P.Study of Effect of Household Parental Smoking on Development of Acute Otitis Media in Children Under 12 Years. Glob J Health Sci. 2015 Sep 2;8(5):50477. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n5p81

19. Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, Abrams DB, Buka SL, Clark MA, Colby SM, Hitsman B, Kazura AN, Lipsitt LP, Lloyd- Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Stanton CA, Stroud LR, Niaura RS. Parental Smoking and Adolescent Smoking Initiation: An Intergenerational Perspective on Tobacco Control. Pediatrics. 2009 Feb;123(2): e274-81.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use. Youth and Tobacco Use. 2019 Feb. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/tobacco_use/index.htm. Accessed May 5, 2019.

21. Christen, A.G, "Tobacco and Your Mouth: The Oral Health's Team of What Tobacco Does to the Oral Cavity," 8-page Educational Pamphlet, The Health Connection, Hagerstown, Maryland. 1991.

22. Christen, A.G., Klein, J.A., Tobacco and Your Oral Health, Quintessence Publishing Co., Carol Stream, Illinois. 1997. pp.1-35.

23. Romito L, Christen A, Coan L. The Oral Effects of Tobacco Use- Recognition and Patient Management. MedEdPORTAL; 2012. Available from: www.mededportal.org/publication/9232.

24. Spiller, M.S. (2010) Dr Martin Spiller's Website - http://www.doctorspiller.com. Accessed October 27, 2010.

25. Tomar, SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: Findings From NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of Periodontology 71(5): 743-751, May, 2000.

26. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Periodontal disease: www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/periodontal_disease/ Accessed November 22, 2014

27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use. Chemicals in Tobacco Smoke. Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health. 2011. Promotion http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2010/consumer_booklet/chemicals_smoke/ Accessed December 24, 2015

28. Hur K, Liang J, Lin SY. The role of secondhand smoke in sinusitis: a systematic review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014 Jan;4(1):22-8. doi: 10.1002/alr.21232. Epub 2013 Oct 7.

29. Tammemagi CM1, Davis RM, Benninger MS, Holm AL, Krajenta R. Secondhand smoke as a potential cause of chronic rhinosinusitis: a case-control study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Apr;136(4):327-34. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.43.

30. Benowitz N. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med. 2010 June 17; 362(24): 2295-2303. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0809890.

31. Christen, J.A., Christen, A.G., "Defining and Addressing Addictions: A Psychological and Sociocultural Perspective," Indiana University School of Dentistry. March 1990. pp.1-182.

32. Smith PH, Rose JS, Mazure CM, Giovino GA, McKee SA. What is the evidence for hardening in the cigarette smoking population? Trends in nicotine dependence in the U.S., 2002-2012. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014 Sep 1;142:333-40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.003. Epub 2014 Jul 14.

33. Clare P, Bradford D, Courtney RJ, Martire K, Mattick RP. The relationship between socioeconomic status and ‘hardcore' smoking over time--greater accumulation of hardened smokers in low-SES than high-SES smokers. Tob Control. 2014 Nov;23(e2):e133-8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051436. Epub 2014 Apr 4.

34. Fernández E, Lugo A, Clancy L, Matsuo K, La Vecchia C, Gallus S. Smoking dependence in 18 European countries: Hard to maintain the hardening hypothesis. Prev Med. 2015 Dec;81:314-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.023. Epub 2015 Oct 9.

35. Gartner C, Scollo M, Marquart L, Mathews R, Hall W. Analysis of national data shows mixed evidence of hardening among Australian smokers. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012 Oct;36(5):408-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00908.x.

36. Christen, A.G., McDonald, J.L., Klein, J.A., et al. A Smoking Cessation Program for the Dental Office, 4th ed. Indiana University School of Dentistry, Indianapolis, IN, 1994. pp.1-51.

37. Christen, A.G., Helping Patients Quit Smoking: Lessons Learned in the Trenches, Quintessence International 29(4):253-259, April 1998.

38. Benson, W., Christen, A.G., Crews, K.M., Madden, T.E., Mecklenburg, R.E., "Tobacco-Use Prevention and Cessation: Dentistry's Role in Promoting Freedom From Tobacco," Journal of the American Dental Association. 131(8):1137-1144. August 2000.

39. Christen, A.G., Tobacco Cessation, the Dental Profession, and the Role of Dental Education. Journal Dental Education 65(4):368-374, April 2001.

40. Henry R, Henderson R. The rise of e-cigarettes. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene, May 2014. http://www.dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/2014/05_May/Features/The_Rise_of_E-Cigarettes.aspx Accessed November 22, 2014

41. Ebbert JO, Agunwamba AA, Rutten LJ Counseling patients on the use of electronic cigarettes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015 Jan;90(1):128-34. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004.

42. Center on Addiction. Recreational Vaping 101. 2018. https://www.centeronaddiction.org/e-cigarettes/recreational-vaping/what-vaping. Accessed May 5, 2019.

43. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quick facts on the use of ecigarettes for kids, teens and young adults. Smoking and Tobacco Use. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/Quick-Facts-on-the-Risks-of-E-cigarettes-for-Kids-Teens-and-Young-Adults.html#what-is-juul. Accessed 5.11.2019.

44. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use. About electroninc cigarettes. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/about-e-cigarettes.html#who-is-using-e-cigarettes

45. Romito LM, Hurwich RA, Eckert GJ. A Snapshot of the Depiction of Electronic Cigarettes in YouTube Videos. Am J Health Behav. 2015 Nov;39(6):823-31. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.6.10.

46. Chen IL. FDA summary of adverse events on electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):615-616.

47. Allen JG, Flanigan SS, LeBlanc M, Vallarino J, MacNaughton P, Stewart JH, Christiani DC Flavoring Chemicals in E-Cigarettes: Diacetyl, 2,3-Pentanedione, and Acetoin in a Sample of 51 Products, Including Fruit-, Candy-, and Cocktail-Flavored E-Cigarettes. Environ Health Perspect. 2015 Dec 8.

48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Newsroom. New CDC study finds dramatic increase in e-cigarette-related calls to poison centers. April 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0403-e-cigarette-poison.html Accessed December 20, 2015.

49. Svetanoff E, Romito LM, Ford PT, Palenik CJ, Davis JM. Tobacco dependence education in U.S. Dental assisting programs' curricula. J Dent Educ. 2015 Apr;79(4):378-87.

50. Romito L, Coan L, Christen A. Practical Counseling and Communication Strategies: Tobacco Cessation. MedEdPORTAL; 2013. Available from: www.mededportal.org/publication/9324.

51. Christen, A.G., Jay SJ, Christen, JA. Tobacco Cessation and Nicotine Replacement for Dental Practice. General Dentistry 51(6), November/December, 2003.

52. ADA®/PDR®Guide to Dental Therapeutics, 5th ed. Appendix P. Chicago, Illinois, American Dental Association, 2009.

53. DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO.Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: a comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addict Behav. 1982;7(2):133-142.

About the Authors

The author serves on the faculty of Indiana University Schools of Dentistry and Medicine, Indianapolis, and University of Southern Indiana, Evansville, IN.

Laura M. Romito, DDS, MS, MBA: Associate Professor, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Comprehensive Care. Director, Indiana University Nicotine Dependence Program.