You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

The ADAA has an obligation to disseminate knowledge in the field of dentistry. Sponsorship of a continuing education program by the ADAA does not necessarily imply endorsement of a particular philosophy, product, or technique.

Accessorizing is important in the fashion industry. Women carefully select shoes and jewelry to complement their clothing, and men choose a coordinating tie and cuff links for their suits. However, for the DHCP one of the most important accessories of their personal protective equipment (PPE) is a well-designed face mask.

Many dental professionals believe face masks protect them from breathing in or inhaling particles in the air. Masks, gloves, gowns, and goggles protect the wearer from large droplets or spatter that may contact the mucous membranes. Further, face masks will offer protection for the patient from the oral or nasal respiratory secretions of the clinician. For optimal patient and provider protection, face masks should cover both the nose and mouth and be worn whenever splash or spatter is anticipated. Masks should fit the face well, pinched onto the bridge of the nose, creating a light seal over the nose and mouth.

Selecting the appropriate face mask, gowns, goggles, and gloves is a key component to minimize the spread of potentially infectious diseases. The appropriate barrier level of the mask, gown, goggles, and gloves must be selected based on the anticipated level of exposure to infection materials during a given procedure.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for Healthcare Personnel

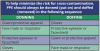

PPE refers to a variety of barriers and respirators used alone or in combination to protect mucous membranes, airways, skin, and clothing from contact with infectious agents. The selection of PPE is based on the nature of the patient interaction and/or the likely mode(s) of transmission. A suggested procedure for donning and removing PPE that will prevent skin or clothing contamination is presented in this lesson (see also Table 1). Designated containers for used disposable or reusable PPE should be placed in a location that is convenient to the site of removal to facilitate disposal and containment of contaminated materials. Hand hygiene is always the final step after removing and disposing of PPE. The following sections highlight the primary uses and methods for selecting this equipment.

Gloves are used to prevent contamination of healthcare personnel hands when 1) anticipating direct contact with blood or body fluids, mucous membranes, nonintact skin and other potentially infectious material; 2) having direct contact with patients who are colonized or infected with pathogens transmitted by the contact route; and 3) handling or touching visibly or potentially contaminated patient care equipment and environmental surfaces. Gloves can protect both patients and healthcare personnel from exposure to infectious material that may be carried on hands. The extent to which gloves will protect healthcare personnel from transmission of bloodborne pathogens following a needlestick or other puncture that penetrates the glove barrier has not been determined. Although gloves may reduce the volume of blood on the external surface of a sharp by 4686%, the residual blood in the lumen of a hollow bore needle would not be affected; therefore, the effect on transmission risk is unknown. Gloves manufactured for healthcare purposes are subject to Federal Drug Administration (FDA) evaluation and clearance. Nonsterile disposable medical gloves made of a variety of materials (e.g., latex, vinyl, nitrile) are available for routine patient care.

The selection of glove type for non-surgical use is based on a number of factors, including the task that is to be performed, anticipated contact with chemicals and chemotherapeutic agents, latex sensitivity, sizing, and facility policies for creating a latex-free environment. For contact with blood and body fluids during non-surgical patient care, a single pair of gloves generally provides adequate barrier protection. However, there is considerable variability among gloves; both the quality of the manufacturing process and type of material influence their barrier effectiveness. While there is little difference in the barrier properties of unused intact gloves, studies have shown repeatedly that vinyl gloves have higher failure rates than latex or nitrile gloves when tested under simulated and actual clinical conditions. For this reason either latex or nitrile gloves are preferable for clinical procedures that require manual dexterity and/or will involve more than brief patient contact. It may be necessary to stock gloves in several sizes. Heavier, reusable utility gloves are indicated for non-patient care activities, such as handling or cleaning contaminated equipment or surfaces.

During patient care, transmission of infectious organisms can be reduced by adhering to the principles of working from "clean" to "dirty" and confining or limiting contamination to surfaces that are directly needed for patient care. It may be necessary to change gloves during the care of a single patient to prevent cross-contamination of body sites. It also may be necessary to change gloves if the patient interaction also involves touching portable computer keyboards or other mobile equipment that is transported from room to room. Discarding gloves between patients is necessary to prevent transmission of infectious material. Gloves must not be washed for subsequent reuse because microorganisms cannot be removed reliably from glove surfaces and continued glove integrity cannot be ensured. Furthermore, glove reuse has been associated with transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and gram-negative bacilli. When gloves are worn in combination with other PPE, they are put on last. Gloves that fit snugly around the wrist are preferred for use with an isolation gown because they will cover the gown cuff and provide a more reliable continuous barrier for the arms, wrists, and hands. Gloves that are removed properly will prevent hand contamination (Figure 1). Hand hygiene following glove removal further ensures that the hands will not carry potentially infectious material that might have penetrated through unrecognized tears or that could contaminate the hands during glove removal.

Isolation Gowns

Isolation gowns are used as specified by Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions, to protect the DCHP's arms and exposed body areas and prevent contamination of clothing with blood, body fluids, and other potentially infectious material. The need for and type of isolation gown selected is based on the nature of the patient interaction, including the anticipated degree of contact with infectious material and potential for blood and body fluid penetration of the barrier. The wearing of isolation gowns and other protective apparel is mandated by the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Clinical and laboratory coats or jackets worn over personal clothing for comfort and/or purposes of identity are not considered PPE. When applying Standard Precautions, an isolation gown is worn only if contact with blood or body fluid is anticipated. However, when Contact Precautions are used (i.e., to prevent transmission of an infectious agent that is not interrupted by Standard Precautions alone and that is associated with environmental contamination), donning of both gown and gloves upon room entry is indicated to address unintentional contact with contaminated environmental surfaces. The routine donning of isolation gowns upon entry into an intensive care unit or other high-risk area does not prevent or influence potential colonization or infection of patients in those areas.

Isolation gowns are always worn in combination with gloves, and with other personal protective equipment (PPE) when indicated. Gowns are usually the first piece of PPE to be donned. Full coverage of the arms and body front from neck to the mid-thigh or below will ensure that clothing and exposed upper body areas are protected. Several gown sizes should be available in a healthcare facility to ensure appropriate coverage for staff members. Isolation gowns should be removed before leaving the patient care area to prevent possible contamination of the environment outside the patient's room. Isolation gowns should be removed in a manner that prevents contamination of clothing or skin. The outer, "contaminated" side of the gown is turned inward and rolled into a bundle, and then discarded into a designated container for waste or linen to contain contamination.

Goggles or Face Shields

Guidance on eye protection for infection control has been published. The eye protection chosen for specific work situations (e.g., goggles or face shield) depends upon the circumstances of exposure, other PPE used, and personal vision needs. Personal eyeglasses and contact lenses are NOT considered adequate eye protection (www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/eye/eye-infectious.html). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) states that eye protection must be comfortable, allow for sufficient peripheral vision, and must be adjustable to ensure a secure fit. It may be necessary to provide several different types, styles, and sizes of protective equipment. Indirectly vented goggles with a manufacturer's anti-fog coating may provide the most reliable practical eye protection from splashes, sprays, and respiratory droplets from multiple angles. Newer styles of goggles may provide better indirect airflow properties to reduce fogging, as well as better peripheral vision and more size options for fitting goggles to different workers. Many styles of goggles fit adequately over prescription glasses with minimal gaps. While effective as eye protection, goggles do not provide splash or spray protection to other parts of the face. The role of goggles, in addition to a mask, in preventing exposure to infectious agents transmitted via respiratory droplets has been studied only for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Reports published in the mid-1980s demonstrated that eye protection reduced occupational transmission of RSV. Whether this was due to preventing hand-eye contact or respiratory droplet-eye contact has not been determined. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that RSV transmission is effectively prevented by adherence to Standard plus Contact Precautions and that for this virus routine use of goggles is not necessary. As compared with goggles, a face shield can provide protection to other facial areas in addition to the eyes. Face shields extending from chin to crown provide better face and eye protection from splashes and sprays; face shields that wrap around the sides may reduce splashes around the edge of the shield. Removal of a face shield, goggles and mask can be performed safely after gloves have been removed, and hand hygiene performed. The ties, ear pieces and/or headband used to secure the equipment to the head are considered "clean" and therefore safe to touch with bare hands. The front of a mask, goggles and face shield are considered contaminated (Figure 2).

How does one appropriately wash eyewear?

Washing with soap and water should be sufficient for the decontamination of protective eyewear. If disinfectants are used, ensure all residual disinfectant is rinsed from all surfaces of the eyewear to prevent the potential for contact with potentially sensitizing disinfectants chemicals. If eyewear is visibly contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious materials, first clean, then disinfect the eyewear with an intermediate-level disinfectant compatible with the eyewear's materials. Consult the manufacturer of the safety glasses, goggles, or side shields to determine appropriate agents.

Hazards in a Dental Office

It is estimated that the human mouth contains trillions of individual bacteria representing well over 500 different species as well as various fungi and viruses. The mouth harbors bacteria and viruses from the nose, throat and respiratory tract; these sources may include various pathogenic organisms such as rhinovirus (common cold), influenza, herpetic viruses, tuberculosis (TB), and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

DHCP are exposed to these microorganisms in a variety of potential hazardous substances on a daily basis: airborne particles, sprays/splashes and aerosols from high speed handpieces and ultrasonic scalers; gases and vapors from waste nitrous oxygen gases and certain dental restorative materials; smoke/plume generated during the use of electrosurgery and lasers; and finally large droplets transmitted by coughing and sneezing.

The terms aerosol and splatter in the dental environment were defined by Micik and colleagues in 1971. Aerosols are particles less than 50 micrometers in diameter and small enough to stay airborne for hours before settling on surfaces or entering the respiratory tract. The smaller particles of an aerosol (0.5 to 10 micrometers in diameter) can pass through the filters of standard face masks and enter into a clinician's airway; however, the level of harm caused by aerosolized particles has not been established.

Splatter (some resources refer to the term "spatter") is defined as particles greater than 50 micrometers with heavier particles that behave in a ballistic manner (bullet-like trajectory arc) and remains airborne only briefly. Splatter can commonly be seen on face shields, protective eyewear, and other surfaces immediately after the dental procedure, but after a short time it may dry clear and not be easily detected. Proper selection and use of PPE (gloves, face mask, eyewear or face shield, and gowns) protect DCHP from these larger particulates. Please note, a face shield does not replace the use of a face mask.

Routes of Transmission

To understand the infection process is the chain of infection, Figure 3 is a circle of links, each representing a component in the cycle. Each link must be present and in sequential order for an infection to occur: there are an adequate number of disease-causing organisms, a reservoir or source for that pathogen, a mode of transmission for the microorganism, an entrance through which the pathogen may enter the host, and a host that is susceptible (i.e., who is not immune). The potential routes for the spread of infection in a dental office are direct contact with body fluids of an infected patient, contact with environmental surfaces or instruments that have been contaminated by the patient, and/or contact with infectious particles from the patient that have become airborne. Effective infection control strategies prevent disease transmission by interrupting one or more links in the chain of infection. This can be accomplished by hand hygiene, proper use of PPE, control of aerosols, and proper disinfection of the treatment room.

Standard Precautions

Introduced in the mid 1980s, universal precautions were a set of infection control and safety procedures to protect against bloodborne disease transmission applied when treating all patients, regardless of health history or presumed infection status.

Standard precautions were introduced in the 1990s which expanded on the major features of universal precautions (designed to reduce the risk of transmission of bloodborne pathogens) as to what fluids are considered infectious. The precautions are designed to reduce the risk of transmission of microorganisms from both recognized and unrecognized sources of infection and assume blood and body fluid of any patient could be infectious. Standard precautions guard against exposure not just to blood, but to all body fluids (except sweat, which is not infectious). This term has gradually replaced the term universal precautions in most health care settings. In dentistry, standard precautions include hand hygiene; engineering and work practice controls; proper handling of patient care items and contaminated surfaces; and PPE. Decisions about PPE use are determined by the type of clinical interaction with the patient.

Regulation and Testing

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the U.S. Government agency that oversees most medical products, foods, and cosmetics. FDA regulates medical devices by evaluating and approving/clearing the products to ensure they are safe and effective. PPE, including masks/respirators, medical gloves, and surgical gowns, intended for use in preventing or treating disease, is considered a medical device and is given a classification. The device/product classification is assigned to one of three regulatory classes based on the level of control necessary to assure the safety and effectiveness of the device. Face masks are considered a Class II (intermediate risk) device.

In 1983, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) made the first recommendations for the prevention of exposure to blood and body fluids through the use of universal precautions. In December 2003, the CDC published its "Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings" (www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5217a1.htm). Although the CDC has no regulatory authority, its recommendations are considered a standard of care and adopted by most state boards as requirements.

The recommendations state that a surgical mask and eye protection with solid side shields, or a full-face shield, be worn to protect mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and mouth during dental procedures likely to generate splashing or spattering of blood or other body fluids.

The CDC categorizes its recommendation on the basis of existing scientific data, theoretical rationale, and applicability. Categories are based on the system used by CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC).

The CDC Guidelines Regarding Face Masks, Protective Eyewear, and Face Shields

1. Wear a surgical mask and eye protection with solid side shields or a face shield to protect mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and mouth during procedures likely to generate splashing or spattering of blood or other body fluids.

2. Change masks between patients or during patient treatment if the mask becomes wet.

3. Clean with soap and water, or if visibly soiled, clean and disinfect reusable facial protective equipment (e.g., clinician and patient protective eyewear or face shields) between patients.

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Standard

The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) International is a globally recognized leader in the development and delivery of international voluntary consensus standards. In April 2011, a new version of the standard specifying performance of face masks was released, ASTM F2100-11. Face mask material performance is based on testing for fluid resistance, bacterial filtration efficiency (BFE), particulate filtration efficiency (PFE), breathability (P-Δ), and flammability. The FDA recognizes ASTM test standards. This standard specifies test results required for labeling mask levels of barrier performance. The ASTM 2100-11 does not evaluate face masks for regulatory approval as respirators, nor address all aspects of face mask design and performance.

Performance Characteristics

Fluid Resistance

Due to sprays, splashes, and splatter generated in dentistry, wearing a fluid resistant mask helps protect the DHCP from mucosal contact with, or inhaling these potentially infectious materials. Face masks are tested on a pass/fail basis at three velocities corresponding to the range of human blood pressure (80, 120, 160 mm Hg). The higher the pressure withstood, the greater the fluid spray and splash resistance. Surgical masks are available with fluid-resistant outer layers and tissue inner layers or fluid-resistant outer and inner layers. (ASTM F1862)

Bacterial (BFE) and Particle (PFE) Filtration Efficiency

Bacterial (BFE) and Particle (PFE) Filtration Efficiency is the effectiveness of a material to prevent passage of bacteria or particles. The results are expressed in the percentage (%) of bacteria or particles that do NOT pass through the fabric. A higher percentage indicates higher filtration efficiency; i.e., 95% BFE or PFE indicates 5% of the aerosolized bacteria or particles used in testing passed through the mask material. Even with high filtering efficiency, some inhaled and/or exhaled air can pass unfiltered around the edges of the mask. The greater the edge leakage of a mask, the lower the actual, in-use BFE and PFE values will be. The bottom line is that a mask is only as good as it fits. (ASTM F2101 and ASTM F2299 respectively)

P-Δ Delta P/Differential Pressure

This measures the resistance of mask materials to air flow which relates to the breathability of the mask. The values are expressed from 1 to 5; the higher the number, the lesser the air flow, and, therefore, the less breathable the material. A comfort scale is expressed as a 1-2 being very cool and a 4-5 being very warm. (Military Standard: MIL-M-36954C)

Flammability

The rate at which the material burns determines the level of flammability; a minimum of a 3.5 second burn rate is required to pass with a Class 1 rating. (Federal Standard: 16 CFR Part 1610)

ASTM Standard

Masks tested using the ASTM Standard F2100-11 specifications will be labeled with levels of barrier performance; the new standard changed mask classifications from performance CLASS (low, medium, high) to LEVELS (1,2,3). The new standard also requires a graphic display on the packaging stating the mask performance level.

ASTM Low Barrier Level 1. Protection Masks would be used for procedures where low amounts of fluid, spray, and/or aerosols are produced.

ASTM Moderate Barrier Level 2. Protection Masks would be used for procedures where moderate to light amounts of fluid, spray, and/or aerosols are produced.

ASTM High Barrier Level 3. Protection Masks would be used where heavy to moderate amounts of fluid, spray, and/or aerosols are produced.

Face Masks vs. Respirators

Following the outbreak of H1N1 in 2009 the CDC came out with interim guidelines for care of patients with confirmed or suspected cases of 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) Virus. Included in these guidelines were recommendations for the use of face masks and/or respirators. Respirators (N95) are designed to seal tightly to the face and filter out small particles that may be breathed in by the wearer.

In healthcare settings the term respirator refers to an N95 or higher filtering face piece as certified by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Respirators are harder to breathe through and are not recommended for long periods of time.

Although bloodborne pathogens such as hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cannot be transmitted by aerosols, other diseases such as tuberculosis can. These particulate respirators, which are designed to provide a tighter face seal than regular masks, can filter out more than 95% of the particles less than 0.1μ. They are appropriate for any health care provider requiring extraordinary respiratory protection, such as when treating patients with active TB.

The risk of tuberculosis transmission in the dental setting is likely very low and is not considered a major occupational health risk for DHCP. Detailed information regarding airborne-transmission precautions and respirator programs is available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/99-143.

Clinical Considerations

Personal protective equipment (PPE) should be worn whenever there is a possibility for occupational exposure to blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM). Even under the best of circumstances leakage can occur during inhalation and while exhaling.

Masks, gowns, goggles, and gloves are considered "appropriate" PPE only if they do not permit blood and OPIM to pass through and reach skin or mucous membranes of the nose, mouth, and hands. Protection can only be expected under normal conditions of use and for the duration of time for which a mask was designed. Various performance expectations require different types of masks, gowns, gloves and goggles.

Under Occupational Safety & Health Association (OSHA) standards, the employer must ensure that employees use appropriate PPE correctly. PPE (masks, gowns, goggles, and gloves) is required to be readily accessible in the correct sizes and proper types for the hazards present. Employers are required to provide PPE at no cost to the employee.

When a face mask is used, it should be changed between patients or during patient treatment if it becomes wet. Changing the mask at this point will reduce the risk of cross-contamination. Once a mask is moistened from either the outside or the inside, a wicking effect occurs and moisture is drawn into the material. Masks worn longer than 20 minutes in an aerosol environment lose their protective quality and can allow wicking to occur. Also, when a mask becomes wet, resistance to the airflow (breathability) through the mask material increases. This causes more air to pass through around the edges of the mask, weakening the seal between the mask and face. Wet masks also may collapse against the skin. Direct contamination quickly results, making the mask an ineffective protective barrier.

Even in dry environments, experts recommend that face masks be changed after 60 minutes, as condensation from the wearer's breath adds moisture to the mask material. Masks are only effective when covering the DHCP's nostrils and mouth. If the DHCP does not like the mask they are wearing for various reasons, he/she should seek out alternatives. It is NEVER acceptable to improperly wear the face mask.

The ADA Makes the Following Recommendations:

• Adjust the mask so that it fits snugly against the face.

• Keep the beard and mustache groomed so as not to interfere with the proper fit.

• Do not touch the front surface of the mask at any time as it is contaminated.

• Remove the mask as soon as treatment is over and dispose of properly; do not leave it dangling from the neck, placed in a pocket or pushed up onto the head.

• When removing the mask, it should be handled by the ties or elastic band without touching the mask.

• Always change the face mask between patients, sooner if it becomes moist.

Promptly dispose of all contaminated PPE and perform hand hygiene immediately after removing all PPE.

Summary

Treating patients in the dental environment presents various contamination issues and potential disease transmission. There is a growing awareness concerning the protection of both the DHCP and the patient. Selection and the appropriate wearing of face masks, gowns, goggles, and gloves based on procedural requirements, is critical to reducing the spread of potentially infectious diseases. The new ASTM F2100-11 standard mask performance rating guides the DHCP on appropriate face mask selection. Standard Precautions should be administered and practiced at all times.

Glossary

Asepsis - practice used to promote a disease/bacteria free field.

Ballistic Manner - having a bullet-like speed of travel.

Doffing - to remove an item of clothing, such as masks, gowns, gloves, or goggles.

Donning - to put on an item of clothing, such as masks, gowns, gloves, or goggles.

Hypoallergenic - having a decreased tendency to promote an allergic reaction.

Malaise - a general feeling of discomfort or uneasiness.

Mucous Membranes - an epithelial tissue that secretes mucous and lines or covers the respiratory passages and other organs.

PPE - stands for personal protective equipment.

Sputum - a mucous that is coughed up from the lower airways.

Wicking - to absorb, or draw off, liquid or moisture.

References

1. ADA Statement on Infection Control in Dentistry. American Dental Association (ADA), (2004, March). Available at: http://www.ada.org/1857.aspx

2. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and ADA Council on Dental Practice. Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996; 127:672-680

3. American Society for Testing and Materials/ASTM International. ASTM F2101-11. Standard Specification for Performance of Materials Used in Medical Face Masks. ASTM; 2011. Available at: http://www.astm.org/Standards/F2100.htm

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings - 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2003, December 19;52 (RR17):1- 61. Consolidates previous recommendations and adds new ones for infection control in dental settings. Accessed December 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5217a1.htm

5. Harrel SK, Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc, Vol. 135, April 2004

6. Millard M, Roe M et al. Masks and Respirators 101: Know the Difference (online CE course). Infection Control Today. Available at: http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/whitepapers/2011/06/masksand-respirators-101-know-the-difference.asp

7. Palenik C. Proper Use and Selection of Masks. 2005, March. Dentistry IQ, PennWell. Available at: http://www.dentistryiq.com/index/display/article-display/225224/articles/dental-office/volume-10/issue-2/focus/proper-use-and-selection-of-masks.html

8. U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSHA Face Sheet. Respiratory Infection Control: Respirators Versus Surgical Masks. Available at: www.osha.gov/Publications/respirators-vs-sugicalmasks-factsheet.html

9. U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 29 CFR Part 1910.133. Personal Protective Equipment; Eye and face protection. Federal Register: March 31, 1999 (Volume 64, Number 61). Accessed December 2011. Available at: http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/dentistry/index.html

10. U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 29 CFR Part 1910.1030. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens. Accessed December 2011 http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=10051

11. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings Jane D. Siegel, MD; Emily Rhinehart, RN MPH CIC; Marguerite Jackson, PhD; Linda Chiarello, RN MS; the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee

About the Authors

Gaylene Baker, RDH, MBA

Gaylene Baker graduated from the University of Iowa with a bachelor's degree in Dental Hygiene, and from Aurora University with her MBA specializing in Marketing. She is a member of the ADHA, AADH, and AAOSH, as well as an e-member of the ADAA. Over the course of her career she has worked in a variety of private practice settings. Currently Gaylene is employed by Crosstex International as the Midwest Sales Consultant.

Revised by:

Janice Lewis, MHA, BSHA, AAHCA, RDA, EFDA

Janice Lewis has been teaching dental assisting for Pima Medical Institute, Houston, Texas, for the last 10 years. She worked for 30 years as an expanded functions dental assistant as a civilian worker for the federal government, from which she is now retired. She received her Master's Degree through the University of Phoenix.