You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Dentistry is a business as well as a health care service profession. It is essential to provide treatment for patients in a caring manner, but it is also necessary to maintain maximum efficiency and production in order to ensure a successful practice. The administrative assistant plays a key role in the smooth operation of any dental practice, from managing accounts, appointments, and inventory to ensuring vital communication between team members and with the patients of the practice. The knowledgeable business assistant not only helps to increase office production, but also assists the dental team in the smooth running of day-to-day operations. This appointment management course focuses on the many procedures and appointments offered by today’s dental offices. The business assistant must have a basic working knowledge of these procedures and therefore maintain an efficient office scheduling system.

Clinical Considerations

Although the administrative team will not be responsible for patient care directly, it is important for them to know basic information about different treatment procedures in case a patient asks questions during scheduling, when making financial arrangements, or speaking on the telephone. Clinical information should only be dispensed with the knowledge and approval of the practice.

Pre-treatment Procedures

Before beginning any dental treatment, the patient’s health history must be reviewed by the patient and dental team members involved. Should the patient require pre-medication before dental prophylaxis or restoration, the dental and physician offices must agree on the protocol and decide who will prescribe the medication(s). Confirmation must be documented in the patient record that the patient followed the medically approved protocol. The dental team often consults with a patient’s physician or specialist to ensure necessary procedures are followed. If the procedure has not been followed, the patient should be required to reschedule the appointment.

Anti-anxiety agents are available for patients who are extremely fearful. Several oral medications exist in pill and liquid forms and can be administered before treatment begins. When these medications are combined with dental treatment, the patient must be advised not to drive to the office, but make arrangements for alternate transportation.

Preventative Procedures

Preventative procedures are performed in the dental practice to prevent dental caries and destruction of natural tooth structure.

The most common preventative procedures are hygiene procedures. These procedures are typically performed by the dental hygienist. However, under certain conditions, they may be performed by the dentist.

Preventative hygiene procedures – Modern dentistry is all about prevention. Dental patients should not only be taught good home care techniques such as brushing and flossing, but they should also receive instructions on other periodontal aids, such as interproximal brushes or irrigation, that are appropriate for each patient’s oral situation. There are many different dental products that can help patients maintain their oral health. A dental professional should utilize those products and tailor them to each patient’s specific needs.

Therapeutic hygiene procedures – Some therapeutic hygiene procedures can include scaling and root planing. Scaling involves the complete removal of plaque and calculus from the teeth. Root planing is the process of planing, or shaving, the root surface with a dental instrument to make it smooth, thus preventing the accumulation of plaque and calculus.

Antimicrobial mouth rinses and antibiotics are sometimes used in conjunction with scaling and root planing. Chlorhexidine is a commonly used antimicrobial mouth rinse. In some cases, the patient may also be prescribed a systemic antibiotic.

Another method consists of inserting fibers impregnated with the antibiotic tetracycline into the gingival sulcus. If periodontal pockets are deeper than 4-5 mm and are not resolved with the above procedures, periodontal surgical procedures can be performed to help the patient keep these areas clean. The key to dental care is making sure the patient has good patient dental education and home care instructions, which will result in faster healing and proper maintenance of the oral cavity.

Pit and fissure sealants are a clear or shaded resin material that is placed in the deep grooves and pits of a tooth surface. Some molars and premolars have deep pits and fissures on the occlusal surfaces and buccal or lingual pits that are virtually impossible for a patient to keep clean, thus making these areas more susceptible to caries formation. Fluoride can be beneficial for the smooth surfaces of the teeth, while pit and fissure sealants can provide protection deep in the pits and grooves.

There are two main types of sealants: light-cured sealants, which polymerize when they are exposed to a curing light; and self-cured sealants, which consist of a base and a catalyst that are mixed together. Sealants can come in different colors such as clear, opaque, or tinted. Sealants can be placed on any premolar or molar that does not have an existing restoration or decay on the intended surface.

Advantages of sealants include sealing of deep pits and grooves so decay cannot penetrate those areas as readily. Sealants can provide excellent caries protection for children through the cavity prone years to prevent decay in molars and premolars that are just erupting. Disadvantages of sealants are that some insurance coverage may be limited by age or type of tooth and the insurance coverage varies from policy to policy. (For more information on Pit and Fissure Sealants, refer to the ADAA course The Use of Pit and Fissure Sealants in Preventive Dentistry.)

A preventative resin restoration (PRR) is placed in the occlusal or biting surface of a tooth. Premolars and molars may have such deep grooves that even sealant material cannot flow into them. A dentist may check the grooves of the teeth with an explorer, and sometimes the grooves can be slightly sticky. The dentist will then use a special preventative resin bur, and clean out or open up those deeper areas. Then a resin can be placed in this minor preparation. A flowable resin or a putty type resin can be used in larger areas, as well as sealant materials that are bonded in the tooth.

One of the advantages with PRRs is that tooth structure can be preserved, as only a small amount is needed be removed to place the restoration. On most occasions, a patient does not require a local anesthetic before the treatment is performed. A disadvantage of PRR is that insurance coverage can vary for adults and children depending on the dental insurance plan.

Restorative Procedures

Restorative procedures are treatment procedures that restore the tooth to optimum health. Typically, this involves a restoration. A patient may have several options in the restoration of his/her tooth. For some individuals, it is a matter of personal preference of a particular material, while for others it may be what the dental plan will pay or the cost itself that dictates which procedures and materials will be used. The following is a brief summary of each of the procedures and materials, along with advantages and disadvantages of the material/treatment option.

Amalgam materials – The first reported use of amalgam as a restorative material dates back to 659 AD in China. Amalgam is a substance that combines two or more different metals, usually silver, copper, zinc, and tin to form an alloy. This alloy is combined with mercury to make dental amalgam. Various groups have tried to have amalgam banned because of the toxicity of mercury in certain situations. Studies continue to show amalgam as a safe, affordable, durable, restorative material, backed by the American Dental Association and governmental agencies. Amalgam is still a common material used for dental restorations today (Figure 1).

Advantages of amalgam include its durability and long lasting restorations, ease of use in hard to reach areas, or in areas where isolation of fluids is a problem. It is time efficient, which is important when children are uncooperative. Disadvantages of amalgam include its color, concerns about mercury content, and the possible need for the removal of healthy tooth structure for mechanical retention. (For more information on mercury refer to the ADAA course Mercury in Dentistry - The Facts.)

Composite materials – Composite materials, similar to amalgam, can be used in restorations to replace missing tooth structure. There are many different types of composite materials on the market today, with varied durability, shade selection and delivery systems.

Advantages of composite include that the tooth colored restorations are more pleasing to the patient and the wide variety of shades allows for creating optimum esthetics. Composite restorations are bonded to the tooth, which can help with better retention of the restoration. Disadvantages of composite restorations include the cost of placement, insurance restrictions on replacement, and at times, patient sensitivity.

Fixed Prosthodontics

Prosthodontics is the dental specialty that pertains to the replacement of missing teeth and tissues. A fixed prosthesis is one that is fabricated outside the mouth and then is permanently cemented in the oral cavity. Examples of fixed prostheses include: inlays, onlays, crowns, veneers, bridges, cantilever or Maryland bridges, implants, and fixed partial or full dentures. A crown is a single unit or two single unit crowns fused together. A bridge is a prosthesis that replaces one or more missing teeth.

Inlays

An inlay is a type of fixed prosthesis that is a conservative approach to restoring a tooth. An inlay is placed inside the coronal portion of the tooth and may involve one or both of the proximal surfaces. Inlays can be made from gold or porcelain. Gold inlays are cemented with dental cement, while porcelain inlays are generally bonded into place with an adhesive.

Advantages of a gold inlay (Figure 2) include: smoother margins of the restoration; a tighter seal between the tooth and restoration allowing the restoration to last longer without fracturing from biting and chewing forces. Disadvantages include the color, the fact that patients have to come back for an additional procedure while the laboratory makes the restoration; and that many insurance plans will downgrade the treatment fee to an amalgam fee.

Porcelain materials used for inlays are made of a glass-silica substrate, closely matched to the patient’s tooth color.

Advantages of porcelain include: tooth colored restorations that are esthetically pleasing and bonded to the tooth for better retention. If using CEREC, the main advantage is a one-appointment procedure. Disadvantages of porcelain include its fragility when compared to other materials, and the two-appointment procedure technique. For some individuals, insurance reimbursement may be lowered if the tooth could have been restored with a less expensive material.

Onlays

An onlay is a fixed prosthesis that is a conservative approach to restoring a tooth instead of placing a full crown. An onlay is placed when an inlay design is not adequate to restore the function of a tooth. Onlays are made from gold or porcelain and cover the occlusal surface as well as one or more cusps of the tooth.

Advantages of gold onlays include: smoother margins of the restoration with a tighter seal against the tooth. Gold onlays (Figure 2) can last longer than porcelain onlays due to less fracturing from biting and chewing forces. Disadvantages of gold onlays include: the color of the restoration, and a two-appointment procedure. Many insurance plans will downgrade the treatment fee or deny coverage all together.

Advantages of porcelain onlays include: a tooth colored restoration that is esthetically pleasing and bonded to the tooth for better retention. Disadvantages of porcelain onlays: they can fracture more easily from biting and chewing forces and two appointments are required. For some individuals, insurance reimbursement may be lowered or denied. When insurance is involved, pre-authorization is always a wise choice.

Crowns

A crown is a single unit or two single unit crowns fused together. Crowns can be made of a gold metal alloy, porcelain or a combination of the two. Appointments for crowns include preparation and impressions in the dental office. Fabrication of the crown is usually completed at an off-site dental laboratory. When scheduling this type of procedure, two procedures are necessary: the first appointment is for preparation of the tooth and taking necessary impressions and the second for delivery of the completed crown and cementation.

There must be enough time between appointments for the lab to make the crown and return it to the office.

Ceramic crowns - Ceramic porcelain is used to fabricate an all porcelain crown. Different types are available at various dental laboratories.

An advantage of an all-ceramic crown is that shades can be custom matched to a patient’s tooth. The ceramic porcelain can match the natural shades of anterior teeth and mimic translucency in the incisal portions of teeth, due to the absence of metal in the crown. Light reflections are more natural in all porcelain restorations. Due to the lack of a metal substrate, the greatest disadvantage is a greater risk of fracture, especially in anterior teeth. A patient may be asked to go to the laboratory for a custom shade (extra time and effort would be needed from the patient). The crown is bonded into place, and therefore may be a longer procedure for the patient.

Porcelain fused-to-metal crown (PFM) – is a crown that uses a metal substructure with a porcelain overlay (Figure 3). Porcelain is used because it is tooth-colored and provides an esthetically pleasing restoration. Porcelain is not as strong as metal, so it is often fused to a metal base for strength, especially when used in the posterior region of the oral cavity.

When a significant amount of tooth has been lost to decay or a large restoration, the cusps can weaken with daily chewing. An advantage to a full coverage PFM is that it can completely cover the tooth with porcelain and have a metal substructure. This provides strength and protection for the remaining natural tooth structure. With proper home care, a patient’s PFM may last for many years. Cementation can take less time by using cements rather than light cured bonding resin cements. A disadvantage is the risk of fracturing the porcelain overlay with heavy bites. Additionally, as the patient ages and recession of the gingiva comes into play, the metal margin of the crown may become visible. Last, there is also a risk of allergies to certain metals contained in the metal substructure of the crown.

Porcelain veneers – A dental laminate or veneer is made from porcelain (Figure 4). A preparation is made on the facial surface of an anterior tooth. A thin layer or sheet of porcelain is fabricated at the laboratory, and the laminate is bonded into place.

One advantage is that patients with misaligned teeth who do not want to have orthodontic treatment can sometimes have veneers placed to straighten out their smile line. Patients with tetracycline staining can use veneers to improve the shade and look of their teeth. Bonding cements that are used in conjunction with veneers can warm up or cool down a shade to maximize a good shade match. Patients can achieve a whiter and /or straighter smile with minimal tooth structure loss, in comparison to having a full crown. Disadvantages include a risk for fractures and the veneers may need to be replaced or repaired more often. Also, there may be no insurance coverage for porcelain veneers.

CEREC – An innovation in fabricating inlays, onlays, and crowns involving CAD/CAM technology. An advantage of the CEREC restoration is that it only requires a single dental appointment. A CEREC restoration is a porcelain inlay, onlay, or crown that is generated from a computer image of the tooth and an in-house milling machine. Once the prepared tooth has received a digital impression and image, the information is sent to a milling machine, which takes the information and mills a block of porcelain to the desired specifications of the restoration. Disadvantages of CEREC crowns include the possibility of easier fracture, as there is no metal substructure under the porcelain, especially in posterior areas where more force is generated when chewing and sensitivity in some individuals. Color choices for crowns are also limited and often the insurance reimbursement is downgraded.

Bridges

A bridge is a fixed prosthesis that replaces one or more missing teeth and is permanently attached to one, two, or more teeth.

Maryland bridge - A Maryland bridge is a conservative approach most often used when a patient has a missing tooth where the adjacent teeth have had little or no restoration. The bridge can be placed in the anterior or posterior segments of the mouth. This restoration includes a pontic that is connected to thin wing-like retainers that are placed on the lingual surfaces of the adjacent teeth.

Cantilever bridge – this is another conservative bridge that has only one abutment tooth and one pontic. This bridge can be used in areas where there will be little stress or no traumatic occlusion.

An advantage to these types of bridges would be their preparation requires little or no reduction of tooth structure and they are cemented in place by using resin bonding to assist in their retention. A disadvantage is because of retention issues, biting pressure, and stress areas, these bridges may have to be re-cemented or redone more often.

Porcelain bridge – Ceramic porcelain is used to fabricate all porcelain bridges. This bridge is created for ultimate esthetics.

Advantages are that porcelain crown/bridge shades can be custom matched to a patient’s tooth; porcelain can bring out more natural shades of anterior teeth and mimic translucency in the incisal portions of teeth, due to the absence of metal in the crown. Disadvantages are that there may be a strength concern with an all porcelain bridge, depending on the length of the bridge, since there is no metal substructure to support extra forces from the bridge. There is a greater risk of fracture, especially in anterior teeth, with all porcelain bridges; and patients may be asked to go to the laboratory for a custom shade, requiring extra time and effort. Also, since the crown is bonded into place, the result is a lengthier procedure time for the patient.

Porcelain fuse-to-metal bridge (PFM) - A PFM bridge is fabricated with a metal substructure with porcelain baked on the outside. Porcelain is used because it is tooth-colored and provides an esthetically pleasing restoration. Porcelain is not as strong as metal, so it is often fused to a metal base for strength, especially in the posterior region of the oral cavity.

Advantages of a PFM bridge include that the patient has the choice of having a fixed restoration vs. a removable prosthetic. This bridge provides more chewing strength in an area where teeth are missing. One of the biggest disadvantages of a PFM bridge is that porcelain can fracture under a heavy bite. The replacement of missing teeth requires the preparation of teeth that may be structurally sound. With every tooth that is replaced, the cost increases. Each false tooth, known as a pontic, is counted as a crown unit. As the patient ages and recession of the gingiva comes into play, the metal margin of the abutments may become visible. There is also a risk of allergies to certain metals contained in the metal substructure of the crown.

Gold bridge – is similar to a PFM bridge, except that the bridge is made out of gold combined with other metals for strength (Figure 5).

Advantages are that the margins are smoother and can be fabricated to be thinner, so the restoration has a better seal against the tooth and the margins are kinder to the gingival tissue. Gold bridges can last longer due to no risk of fracturing from biting and chewing forces as seen in porcelain and porcelain fused to metal restorations, prolonging the life of the restoration. For the patient, the cost of gold versus porcelain fused to metal restorations is the same. The primary disadvantage of gold is the color.

Removable Prosthodontics

Removable prosthodontics are included in the prosthodontics specialty, although many general practitioners provide the service. Removable prostheses include various types of partial dentures (Figure 6) and complete dentures.

Partial Denture

A partial denture replaces one or more missing teeth and can be prepared in many different styles. The most common type is a clasp retainer style. Partial dentures can require semi-precision or precision attachments for retention of the appliance in the oral cavity. A partial denture can be fabricated from all acrylic, or more commonly, a cast framework of palladium with acrylic or porcelain teeth added. Most clasps on a partial denture are metal or part of the cast framework, but some dental laboratories are using strong plastics for clasps as well. A unilateral partial is a removable prosthesis that replaces missing teeth on one side of the mouth. A bar and clasp or clasps are made to extend to the opposite side of the oral cavity for stability of the partial. A bilateral partial is a removable prosthesis that replaces missing teeth on both sides of the mouth. A bar and/or clasps are set on the remaining teeth to add stability to the appliance.

Advantages of partial dentures are teeth can be replaced in areas where bridges are not feasible. Partial dentures can replace chewing ability in areas of tooth loss, but often to a lesser efficiency than natural teeth. Disadvantages are that partial dentures are a removable prosthesis, and a patient may dislike removing them for daily cleaning. Partial dentures may become loose over time, and can cause sore areas on tissue from rubbing. Substantial weight gain or loss will affect the fit of the prosthesis. For patients with poor oral hygiene habits, the clasps surrounding teeth can trap food debris and areas can decay. Unilateral partials are not very stable and may affect eating and speaking for some patients. Clasps can break or bend, and the acrylic can break if dropped.

Provisional Appliances

Provisional appliances are provisional partial dentures, commonly known as a “flipper” that is used to replace a missing tooth or teeth during the healing phase of treatment. When multiple teeth are removed, bone and gingival areas need additional time to heal. A flipper can supply the patient with esthetics, help with tooth function in those areas, and keep the remaining teeth in position until they are ready for more permanent cast prosthesis.

Complete Denture

A complete denture, also known as a full denture, can be made from acrylic but can include metal for reinforcement in the palatal area. A complete denture replaces all of the missing teeth in an arch. Patients can function with one or both arches replaced by complete dentures.

Advantages are that complete dentures replace all of the missing teeth and structures when needed. Dentures can help patients chew more easily, although chewing efficiency is only 20% of the natural dentition. One disadvantage is that the lower dentures are sometimes difficult to keep in place, and can wear away the lower ridge of bone over time, causing more difficulties with chewing and denture stability. Also, patients may have difficulty chewing some foods, as well as speaking clearly and will need to learn to adapt. Dentures can cause sore areas and can make it painful for patients to eat and talk. It is important that dentures be removed daily for a period of time to allow tissue to rest. The appliance must be carefully cleaned, as dropping it can cause it to break.

Immediate Denture

It is common practice to remove some of the posterior teeth prior to taking an impression for an immediate denture. This allows the tissue to heal without forcing the patient to go totally edentulous until the appliance is fabricated. These dentures are made from acrylic but can include metal for reinforcement in the palatal area. Immediate dentures are promptly inserted in the patient’s mouth after the extraction of any remaining teeth. A soft tissue conditioner is placed inside the portion of the appliance that rests on the tissue. It acts as a cushion and aids in healing.

Advantages are that a patient can have a denture placed immediately after extractions, allowing the denture to assist in keeping food and other debris out of the surgical areas and guiding the tissue to heal in the shape of the denture during healing. Disadvantages: the denture can become loose or ill fitting after bone and tissue heal from the extraction areas. The need for frequent return visits to the dental office for replacement of the tissue liners can be a constraint on the patient’s time. Insurance coverage sometimes dictates when a patient can have an immediate denture relined. Most often it is six months. A patient may have more sore spots as the extraction sites are healing and the underlying bone is changing. A patient may need multiple visits to relieve those areas. An immediate denture usually needs to be remade after a period of time for a more comfortable fit. Again, insurance coverage may dictate the frequency of remakes. Immediate dentures tend to be costlier than regular dentures because of the relining materials and visits.

Surgical Procedures

There are many types of surgical procedures available in dentistry. Many general practitioners enjoy the challenge of surgical procedures. However, many refer to an oral surgeon for more complicated cases. Some of the more common procedures are listed below:

Dental Implants

An implant is a metal cylinder acting as a root form that is placed into the bone of the mouth to replace missing teeth. It is made from titanium, and is surgically embedded into the bone and it will actually fuse to the bone through a process called osseointegration. An oral surgeon usually places the implant, and the general dentist will place the final restoration, a crown, bridge or denture.

Advantages of implants are that they are beneficial in replacing teeth in areas where teeth on either side of it have no previous restorations, especially anterior teeth where one tooth is missing. They can be successful in adding retention to lower dentures where the mandibular ridge has been worn and the denture has no stability. Disadvantages: cost can be a factor for most patients, as insurance companies most often do not provide coverage. Also, the implant process can vary in time depending on the area, type of implant, the patient’s oral hygiene and healing time.

Extractions

An extraction is a removal of a tooth. Teeth can be removed under local anesthesia, or general anesthesia. Rarely does a patient undergo the procedure without some type of anesthesia. Extractions can be classified as simple, complicated, or impacted.

A simple extraction typically involves a partially or fully erupted tooth, with little or no difficulty in removing the tooth.

Complicated extractions can begin as simple extractions, but can evolve into something more intricate during the procedure. Examples of complication may result from root tips breaking off, a sinus perforation, or excessive bone removal.

Impacted extractions involve the uncovering of the unerupted tooth and often involve cutting away some bone and tissue. The patient usually leaves the appointment with sutures, which may or may not need to be removed within a short period of time.

As with any type of dental treatment, the extent of discomfort and time required for healing will vary from patient to patient. A common consequence for some mandibular extractions is a “dry-socket” (loss of a clot). This condition occurs 3-5 days after treatment. This is a painful condition where the patient will need to return to the practice to have the extraction site flushed with a saline solution and packed with a dressing material that encourages new clot formation.

Bleaching Procedures

Bleaching can be effective for lightening teeth that have become dark or discolored as a result of stains from foods or beverages, oral habits, aging, fluorosis, or tetracycline. Teeth that have undergone endodontic treatment can also become dark, and bleaching can be effective for these non-vital teeth as well. Bleaching is done either in the dental practice or at home, or a combination of the two may be utilized. Before bleaching begins, the current shade of the patient’s teeth is recorded, and photographs may be taken.

The advantages of bleaching procedures include a whiter and brighter smile, which can boost self-esteem of a patient and can lead to other dental procedures that may make their smiles more esthetic. Disadvantages: Bleaching procedures can cause sensitivity, although it is short term in duration. Results are not guaranteed, and certain food may stain teeth over time; a patient may have to do additional bleaching at home and/or in the dental practice. The patient is instructed to refrain from eating certain foods directly after bleaching to maintain bleaching results for a longer duration.

Note: The American Dental Association does not endorse bleaching by an unlicensed dentist.

Endodontic Procedures

When a tooth presents symptoms that indicate that the nerve inside the tooth is dying, the root canal inside the tooth must be treated with root canal therapy (RCT). These symptoms may include a sensitivity that lingers to cold, hot, or biting pressure. A tooth can also become infected and can have an abscess or fistula on the gingiva below the tooth. It may or may not be evident on a radiographic image; a dentist will perform tests to determine if the tooth is still vital. This is just one of many endodontic treatment procedures performed in dentistry.

The advantage to a root canal treatment is that it can provide a patient with pain relief. If a tooth is broken down severely, an RCT can aid in the placement of pins or a post to help strengthen the tooth while it is being rebuilt. RCTs can save teeth that may otherwise be doomed. Disadvantages: RCTs can sometimes increase the risk for fractured teeth because once the nerve is removed, the tooth becomes brittle and more fragile, necessitating the placement of a crown on the tooth. Sometimes a tooth that has had RCT may need to have further treatment done due to infections, fractures, or additional canals not seen on the initial radiographic image.

Orthodontic Procedures

While many general practitioners refer these cases, several offices may also engage in minor orthodontic therapies (Figure 7). After cases have been presented, the office will schedule several timely appointments to restore a patient to proper occlusion. Treatment plans can include the use of brackets and wires, retainers, and appliances that reshape the oral cavity and realign the dental arches. Proper and timely scheduling is a key factor in orthodontic treatment and a working knowledge of anticipated procedures is critical. Time must be available in the schedule for orthodontic patients who require bracket re-bonding or other minor dilemmas that if not treated in a timely manner, may lengthen the overall treatment schedule.

Post-Operative Instructions

Upon completion of any dental treatment in the office, time must be reserved to offer post-operative instructions and explanations. These instructions often include information on how to care for the patient or restoration during the next hours and days after treatment. Also included in the instructions should be information about possible duration of anesthesia, eating and rinsing instructions, extended follow-up care, and additional appointments in the future.

When the patient is a minor, the instructions should be given to a parent or guardian. Cautions should include watching that the child does not bite lips, cheeks or his/her tongue while the mouth is numb, and also reiterating concerns about brushing, flossing, and the importance of fluoride.

Radiography

Radiography involves both the administrative and clinical team. Some basic information about radiology is necessary to order supplies, pull radiographic images for insurance processing, or answer a patient’s questions.

Technique

Dental offices currently have a choice in obtaining the radiographic images of their patients. The office can choose to use a film-based technique, or choose to use image receptors or sensors that create a digital image which requires computer processing. As in film-based radiography, digital imaging requires x-ray interaction with a receptor, latent image processer and image viewer. The receptors (direct or indirect sensors) used in digital imaging are faster, and more sensitive thus requiring less radiation than film. The energy received by the receptor must be converted to digital data before it becomes usable.

Types of Film

There are several types of film used in dentistry today. Intraoral films are categorized according to size of the film packet, using numbers 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 (Table 1, Figure 8 and Figure 9). The size of the film packet corresponds to the number.

Normally, it is best to attempt to use the largest intraoral film that can fit within the area being examined, in order to obtain a view of the entire anatomical area of interest. Very few patients consider periapical film to be comfortable; however, with an experienced operator the procedure should take relatively little time and placement of the film packet is usually endured during the exposure time needed. Films are placed vertically in the mouth for anterior periapicals and placed horizontally for posterior periapical and bitewing views. Bitewings may be positioned either horizontally or vertically, depending on the patient’s level of crestal bone.

Types of Receptors

Digital receptors come in two basic formats; rigid wired, or wireless, sensors or phosphor plates. Rigid digital receptors are categorized as direct sensors. Photostimulable phosphor plates (PSP), also known as storage phosphor plates (SPP), are another type. PSP are categorized as indirect digital sensors as they require a scanning process to digitize the image. PSP are flexible, wireless receptors similar in size and thickness to film. Phosphor plates are available in the same sizes as intraoral film including 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Duplication of Radiographic Images

Recently, it has become indispensable to be able to duplicate existing radiographic images for various reasons, such as: to provide verification for dental insurance carriers, for second opinions of dental care, for medical/legal uses, etc. The capability to duplicate an existing image may also prevent the need for a repeat film on a patient, therefore reducing his or her overall exposure to ionizing radiation. At times the quality of existing images may be improved by use of film duplication techniques.

While this procedure does not require an appointment, it does require staff time. Should a duplicated image or images be necessary, time must be allowed in the schedule to complete this procedure.

Patient Concerns About Radiation

Often patients like to know the risks involved with the dose of radiation they are receiving or going to be receiving. Generally, to convey dosages or exposures in numerical terms is insignificant to most patients. An alternative to stating dosages in terms of numbers is a comparative dose that would be received from other events, to which the patient might better relate. If a full mouth radiographic series (FMX) were exposed on an individual, he or she would receive a dose of radiation similar to that received if he or she:

- Lived at sea level for 65 days – characteristic for most of the US

- Flew 5 hours in an airplane at a 30,000-foot elevation

- Lived in Denver for 30 days (higher elevation)

The dose of radiation received from an FMX is NOT equivalent to a day at the beach in the sun! Ionizing radiation is around us all the time. Everyone in the world receives some amount of ionizing radiation just from living on this planet. Every day we are exposed to radiation from radon in the soil, cosmic rays from outer space, radioactive substances found in building materials, and from radioactive substances found within our own bodies.

A key for patient compliance is to relate the importance of prescribed dental radiographic images. Their benefits far outweigh the negative effects when used properly for diagnostic and preventative purposes.

Infection Control

The administrative team in the dental practice may have very little to do with reprocessing of dental instruments. Infrequently, an assistant who is cross-trained may be called upon to help out with the processing of instruments. Frequently, however, patients will ask questions of both the clinical and administrative team about the process of “cleaning” the instrument for the next patient. This section briefly covers the basics of infection control in dentistry.

Personal health and safety is crucial in every dental practice. The well being of healthcare providers, administrators, patients and society is very important, especially when these areas are in constant change with new products, technology and processes. With all of these new and improved options, dentistry is bombarded on a regular basis by governmental agencies and professional associations who regularly release new rules, regulations and recommendations to make the practice of dentistry safer to all parties involved. Dental practices are required to comply with certain requirements, but the methods involved often seem complex, time consuming and relatively expensive. However, there really is no alternative to an effective workplace health and safety program. Each dental practice must make the commitment to establish and maintain a safe work and treatment environment for the dental team and their patients alike.

Preventing Cross-Contamination

Protocols to comply with infection control procedures do affect the daily schedule. The clinical areas of the dental practice have specific protocols for setting up and tearing down treatment rooms. In healthcare, there is no room for shortcuts. Many offices use barriers to assist in the prevention of cross-contamination. The degree to which an office uses barriers can also vary greatly. Some practices will cover everything in sight, while others will barrier the items used in the immediate area of treatment that is difficult to disinfect. Another means of preventing cross-contamination is the use of disposable items.

Cleaning - Before anything can be disinfected or sterilized it must be cleaned. There are two basic methods of mechanical cleaning used in dentistry today.

- The first method is by ultrasonic cleaner, which consists of a chamber that instruments are placed into. A solution of water and detergent clean instruments as the unit creates sonic waves that produce cavitations, the mechanical means of cleaning instruments. Instruments are usually in this cleaner for approximately 10 minutes.

- The second mechanical cleaning method is the use of instrument washers, which clean more efficiently and effectively than hand scrubbing. Customarily used in central sterilization services of hospitals and dental schools, these devices are relatively new to the dental industry.

Hand cleaning is not recommended; if hand cleaning must be used, the operator should use a long handled brush. The instrument should be placed under water and scrubbed away from the operator.

After such cleaning procedures are completed, additional time is added for sterilization and instrument cool down. Procedures must be timed so that proper protocols are continually followed and that enough instruments and set ups are available for every procedure scheduled each day.

Disinfection - For years, dental offices have relied on chemical germicides to decontaminate surfaces and equipment in the treatment areas that are not removable for sterilization. Disinfection differs from sterilization in its lack of spore killing activity. Disinfectants are not capable of achieving sterilization, and heat sterilization is always the preferable method for sterilization of instruments used in the patient’s mouth, or those contaminated with body fluids.

The protocol in the treatment areas involve a spray – wipe – spray technique that takes time to complete between each patient. The operatory must remain untouched for approximately 10 minutes before the room can be set up again for the next treatment.

Sterilization - Sterilization removes all pathogens and is the process used to make certain that instruments and devices that come into contact with the patient’s oral tissues are free from contamination from a previous contact.

General Patient Management

Dentistry is both a health care system and a business. In order to have a successful and thriving dental practice, the dental team must understand the patients they serve.

Patient Types

Each dental staff member should have an understanding of the basic drives involved in motivating their patients. Unless the entire dental team can understand these drives, they will become discouraged after numerous attempts fail to motivate their patients to value “top-notch dentistry.”

Patient Needs - The well-known works of the humanistic psychologist, Abraham H. Maslow, can be applied to the dental patient. Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” (Figure 10) explains how an individual’s needs motivate behavior. Maslow identified five basic levels of needs ranging from basic biological needs to complex social/psychological drives with the most fulfilling of needs at the top. Individuals may move back and forth from one level of need to another depending on the circumstances at any given time. The ability to gain consent for treatment and make appointments accordingly directly affect the daily schedule.

To relate Maslow’s hierarchy to dentistry, the dental team must get to know their patients. Before the dental team can motivate a patient to accept a certain type of dental treatment, it must be understood where the patient is on the hierarchy of needs. Setting up financial arrangements for a dental patient often exposes a conflict of needs. The patient must make certain that basic needs of food, housing, and clothing are met, and yet there may be a desire to meet social needs by improving appearance with some form of dental treatment. A conflict arises in the decision making process when the patient is confronted with the dilemma of how to satisfy all of these needs on a specified income. The dental team must make an effort to determine the patient’s needs, realize the patient’s potential conflict, and consider presenting an alternative treatment plan so the patient has some treatment and/or financial options.

Special Needs - Accommodations may be necessary in order to treat patients with special needs. At times, the caregiver may need to be in the treatment area while treatment is ongoing, to help assist the patient down the hall, or assist the hearing or visually impaired patient with communication. Special adjustments may be needed in the scheduling of certain patients, providing for extra time or specific times during the day.

Accommodations to the treatment schedule may include options of anesthesia. While some patients require no, little, or standard amounts and types of anesthesia, other patients may request more profound methods. Some patients, including those with extreme anxiety or small children, may be prescribed a sedative medication. Conscious sedation methods can be introduced to patients in the form of oral medication, inhalation (“laughing gas”), or with proper training, the dentist can use intravenous or intramuscular methods. If a patient requests or requires these methods, the schedule should reflect extra time to accommodate the procedure.

Medical Emergencies

Medical emergencies do happen in the dental office. It is essential that the entire dental team, clinical and administrative, be prepared to handle any emergency should one occur.

There are several factors that may increase the incidence of a medical emergency occurring in a dental practice. They include:

- A pregnant patient

- An increase in the use of prescription drugs

- An increase in the use of nonprescription drugs and herbal supplements that may interact with certain dental procedures or medications used

- A higher incidence in recreational drug use

- An increase in outpatient care allowing many patients to be treated in the dental office who would not otherwise normally be seen for care

- Increased stress on medically compromised patients when longer dental appointments are scheduled

- And a substantial increase in the number of patients over the age of 65 years seeking continuing dental care

If a medical emergency occurs within a practice, it generally occurs during and after the delivery of local anesthesia. Stressful procedures that cause anxiety to the patient, even before the appointment, include the extraction of teeth and endodontic therapy. A patient’s anxiety level may be very high during these procedures; pain control may be difficult, resulting in a greater risk for a medical crisis. If the patient has been in the supine position for an extended period of time, he/she may become “light headed” while scheduling the next appointment. The entire dental team must always be prepared for any predicament, large or small, particularly at these times. Immediate response is required of all personnel during an emergency, and preparation allows for an appropriate response.

It is usually the dental practice administrator’s responsibility to post and update emergency telephone numbers. A listing of important numbers is normally posted near every phone in the practice area with specific numbers such as 911 being programmed on speed dial.

Common Medical Emergencies in the Dental Practice

The following section pertains to the most common medical emergencies seen in dentistry today. Treatment considerations for both treatment areas and administrative areas are given as the administrative staff may be called upon to assist in treatment areas. It is important to know the patients, and check their health history when scheduling appointments. Being prepared for possible emergencies and scheduling the treatments accordingly will negate possible emergencies and scheduling delays.

Syncope (fainting): Syncope is the loss of consciousness caused by decreased blood flow to the brain. It is the most common medical emergency in the dental office. There are many reasons why a patient may faint in the dental office. Psychological factors include, but are not limited to: stress, anxiety, trepidation, and pain, while physical factors include exhaustion, hunger, and remaining in one position for a long period of time. For most patients, there are warning signs that one is ready to faint. Table 2 compares the signs and symptoms of pre-syncope with those of syncope.

To treat syncope:

- Stop dental treatment and remove any objects from patient’s mouth

- Place patient in a supine position with the feet slightly elevated; if pregnant, place patient on her side and loosen any tight clothing around the neck

- Establish/maintain open airway, administer oxygen and monitor vital signs

- Use ammonia capsule under the nose

- Once consciousness is regained, keep patient calm and comfortable and do not move until fully recovered with vital signs at baseline readings; record all information in patient’s record

Syncope frequently occurs in the reception area of dental practices. Similar treatment measures would be taken in the reception area once another team member notified the doctor of the occurrence.

Hyperventilation: Hyperventilation (Table 3) is an increase in the rate or depth of breathing resulting in a decrease in carbon dioxide levels in the blood. This condition is most commonly caused by anxiety and often occurs prior to syncope.

To stop hyperventilation:

- Stop dental treatment, remove any objects from the patient’s mouth and place patient in an upright position; loosen tight clothing around the neck

- Calm the patient, and explain what is happening; have the patient take deep, slow breaths

- Never administer oxygen to a patient who is hyperventilating

- Record all information in patient’s record

Hyperventilation frequently occurs in the reception area of dental practices while the patient is waiting to be called back for dental treatment. Similar treatment measures would be taken in the reception area once another team member notified the doctor of the occurrence.

Pregnancy: Several common things that take place during pregnancy can pose difficulty for a female dental patient. Through 40 weeks of a full-term pregnancy, her body adapts to the baby and works harder. Vital signs may show variations from her previous office visits. An elevation in blood pressure is common but must be monitored.

Other cardiovascular issues may arise: anemia, edema of the ankles, and shortness of breath are common but usually don’t need any special alterations of dental treatment. As a baby grows, it pushes its mother’s stomach and diaphragm upward and her intestines decrease in motility. She may have an increased gag reflex that could cause problems for any procedure. Some women may have problems with gastroesophageal reflux and constipation. Morning sickness is common and may cause permanent damage to the tooth enamel. The patient should rinse her mouth with water after vomiting rather than causing further damage with toothbrush abrasion.

Throughout pregnancy, hormones fluctuate. The development of pregnancy gingivitis and gingival granulomas is believed to be caused by these changes in hormones. Pregnancy may lead to development or worsening of several oral problems such as erosion, and tooth mobility.

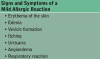

Asthma attack: An asthma attack (Table 4) is a respiratory disorder in which the airways in the lungs become narrow, causing difficulty in breathing. There are many causes that can trigger an attack: exposure to allergens such as dust, pollen, animals, and certain foods; an upper respiratory or bronchial infection and anxiety or emotional upset.

To treat an asthma attack:

- Stop dental treatment and remove all objects from patient’s mouth

- Place the patient in an upright position and administer patient’s bronchodilator; administer oxygen

- If above steps fail to relieve the attack, administer epinephrine IV

- If all treatment is unsuccessful, call for medical assistance

- Record all information in patient’s record

Similar treatment measures should be taken in the reception area once another team member notified the doctor of the occurrence. In the cases where the attack continues after administering the bronchodilator, the patient should be escorted to an available treatment room for medical treatment and the scheduled appointment rescheduled.

Allergic reaction: Allergic reactions (Table 5) are a hypersensitive reaction to a foreign substance, an allergen, which has entered the body. Although the body can normally destroy allergens, there are times it cannot. If the allergen is not destroyed, the body releases the chemical, histamine, which may result in an allergic reaction. Allergic reactions can occur in varying degrees of severity, from a skin rash to cardiac arrest, to even death. Severe reactions are called anaphylaxis. The reactions may be delayed for several hours and even days after exposure to the allergen, or they may occur immediately upon exposure. Reactions may be localized, or they can involve the entire body. In general, the longer the time that passes between the exposure and the onset of the reaction, the less severe the reaction.

The type of allergic reaction will also depend on the type and amount of allergen to which the individual was exposed. In the dental office, typical reactions are to latex products (for those individuals with latex sensitivity or latex allergies), antibiotics, impression materials, local anesthetics, and toothpaste. A common food allergy that is on the rise, especially in the younger generation, is an allergy to peanuts. Healthcare practitioners frequently consume peanut butter between patient visits, as it is a great source of energy to tide one over until mealtime. It is imperative that no one on staff consumes peanut products on a day that a patient with a known peanut allergy is appointed. Just smelling it on one’s breath can trigger a life-threatening reaction in some individuals.

To treat a mild allergic reaction, remove the cause of irritation and administer antihistamine or corticosteroid. Dental treatment may need to be suspended depending on the severity of the reaction.

In the reception area, remove the irritant or move the patient into another area away from the irritant and notify the doctor.

Anaphylactic reaction: Anaphylactic reaction (Table 6) is a severe allergic reaction, and can develop almost immediately after the patient is exposed to an allergen. This type of response requires immediate treatment and can prove to be fatal if the correct treatment is not provided in a timely manner. The severity of the reaction depends on the amount of acquired sensitivity, the amount of allergen that entered the body, and the route of entry into the body. The sooner the symptoms occur after the exposure, the more severe the reaction will be, and the more critical for immediate treatment.

To treat an anaphylactic reaction:

- Call for medical assistance

- Place patient in supine position and administer oxygen

- Administer epinephrine injection if there are definite signs of an allergic reaction - auto-inject “epi” pens should be standard to every dental office emergency kit; adult and junior dosage

- Administer antihistamine, as needed

- Initiate CPR, if needed depending on severity of reaction

- If respiratory system begins failing due to swelling of the oral tissues, the dentist may need to perform a cricotracheotomy

- Monitor and record vital signs

- Record all information in patient’s record

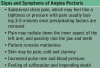

Angina pectoris: Angina pectoris (Table 7) is acute chest pain caused by a decreased blood supply to the heart as a result of diminished capacity of the blood to carry oxygen, or increased workload in the heart. There are certain precipitating factors such as emotional stress, exposure to intense cold and physical exertion that can trigger the pain.

To treat angina pectoris:

- Stop dental treatment, remove all items from patient’s mouth and place patient in a comfortable position – this is usually in an upright position

- Loosen tight clothing from around the neck, administer nitroglycerin sublingually and administer oxygen

- Administer a second dose of nitroglycerin if symptoms are still occurring five minutes after the first dose

- Administer a third dose of nitroglycerin, if needed, five minutes after second dose

- Suspect myocardial infarction if symptoms persist after third dose of nitroglycerin

- Call for medical assistance (call for medical assistance at start of symptoms for patients with no prior history of angina)

- Monitor vital signs and record all information in patient’s record

If angina symptoms occur in the reception area, escort the patient to an available treatment room and summon the dentist.

Acute myocardial infarction (MI): An acute myocardial infarction (Table 8), or heart attack, is the destruction of a part of the cardiac muscle due to lack of oxygen. Causes of a MI include an obstruction in a coronary artery that occurs with atherosclerosis, preventing an adequate blood supply to the area of the heart.

To treat a myocardial infarction:

- Stop dental treatment, remove all objects from patient’s mouth and try to keep the patient calm

- Administer nitroglycerin

- Call for medical assistance if symptoms are not relieved by nitroglycerin

- Place the patient in a comfortable position - usually a seated position

- Administer oxygen

- Administer an analgesic for pain

- Be prepared for CPR, if needed

- Monitor and record vital signs

- Record all information in patient’s record

When a patient exhibits signs and symptoms of a myocardial infarction in the reception area, alert the dentist and remain with the patient until the dentist arrives.

Women often have very different symptoms when experiencing a heart attack including shortness of breath, pressure or pain in the lower chest or upper abdomen, dizziness, light-headedness, fainting, upper back pressure, or extreme fatigue.

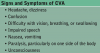

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA): A cerebrovascular accident (Table 9), more commonly known as a stroke, is damage to the brain that results in a loss of brain function. The damage occurs as a result of an interruption of blood flow to the brain. There are four causes of stroke: cerebral embolism, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, and cerebral thrombosis.

To treat a CVA:

- Stop dental treatment, remove all objects from patient’s mouth

- Place the patient in an upright position, with head slightly elevated

- Call for medical assistance

- Administer oxygen and monitor vital signs

- Keep the patient calm and be prepared for CPR, if needed

- Record all information in patient’s record

When a patient exhibits signs and symptoms of a CVA in the reception area, alert the dentist and remain with the patient until the dentist arrives.

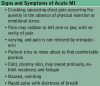

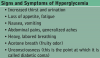

Hyperglycemia (diabetic coma): Hyperglycemia (Table 10) is an excess of glucose in the blood. It occurs in persons with diabetes. It has a slow onset, and the patient will experience symptoms days prior to the onset. The cause of hyperglycemia is a deficiency or complete lack of insulin in the diabetic individual.

To treat hyperglycemia:

- Stop dental treatment and if conscious, have the patient administer own insulin, if available

- Call for medical assistance

- If unconscious, transport to a medical facility immediately (do not administer insulin to an unconscious individual)

- Provide basic life support while monitoring all vital signs

- Record all information in patient’s record

When a patient exhibits signs and symptoms of a diabetic coma in the reception area, alert the dentist, and remain with the patient until the dentist arrives.

Hypoglycemia (insulin shock): Hypoglycemia (Table 11) is too little glucose in the blood. It has a rapid onset, unlike hyperglycemia, which has a slow onset. The cause of hypoglycemia is often the result of the diabetic individual having missed a meal, or not eaten a balanced diet resulting in a high insulin level and low glucose levels. Another cause includes excessive exercise without a proper balance of food and insulin or an excessive dose of insulin.

To treat hypoglycemia:

- Stop dental treatment

- If conscious, administer a sugar source such as a glass of orange juice or cake icing

- If unconscious, place a thin strip of cake icing on the inside of the lip (do not administer any other type of sugar source orally to an unconscious individual)

- Call for medical assistance

- Administer an IV injection of 50% dextrose or glucagon

- Monitor vital signs

- If patient regains consciousness, administer another source of sugar, such as orange juice

- Record all information in patient’s record

When a patient exhibits signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia in the reception area, alert the dentist, and remain with the patient until the dentist arrives.

Seizures: Seizures (Table 12) are characterized by a sudden, involuntary series of muscle contractions that result from overexcitement of neurons in the brain. Causes of seizures include epilepsy and toxic reactions to local anesthetic. Fatigue, physical or psychological stressors, and/or flashing lights are precipitating factors for seizures.

To treat a seizure:

- Stop dental treatment, remove all objects from patient’s mouth and remove all equipment or materials that may cause injury to the patient; remove glasses and loosen clothing

- Call for medical assistance

- Lower the patient to the floor if there are objects which cannot be moved and might injure the patient; do not restrain the patient

- Monitor and record vital signs

- Prepare an anticonvulsant drug (diazepam) in case it is needed (if seizure lasts more than five minutes)

- After the seizure is over, place patient on one side

- Reassure patient, and allow time for recovery

- Record all information in the patient’s record

When a patient exhibits signs and symptoms of a seizure in the reception area, alert the dentist, and remain with the patient until the dentist arrives.

Adrenal crisis (acute adrenal insufficiency): An adrenal crisis (Table 13) is an acute, life-threatening state in which the adrenal gland is unable to produce sufficient corticosteroids, which are substances that help the body respond to stress. When a patient who is on long-term steroid therapy is subjected to stress, such as dental treatment, the body will not be able to respond to the stressful situation by producing additional steroids, and the patient will have an adrenal crisis. To counter this, the patient’s dose of steroids must be increased prior to the stressful situation.

To treat an adrenal crisis:

- Stop dental treatment and place patient in a supine position

- Call for medical assistance and administer hydrocortisone by injection

- Administer oxygen

- Monitor vital signs

- Record all information in patient’s record

When a patient exhibits signs and symptoms of an adrenal crisis in the reception area, alert the dentist, and remain with the patient until the dentist arrives.

Appointment Control

Effective time management is essential to the success of any dental practice. The appointment schedule is the mechanism for controlling time by allotted time increments to scheduled appointments, lunch breaks, team meetings, and days off for personal time, holidays, vacations and professional conferences.

The scheduling coordinator or scheduling manager has the difficult task of maintaining a smooth flow of patients during all hours of the day. An understanding of clinical procedures and possible emergencies, as mentioned previously, and also understanding what expanded functions can legally be delegated to individual members of the dental team, can facilitate in making this task effortless. The employment of an expanded duties dental assistant can create opportunities for the dentist to increase daily production.

Appointment control allows the coordinator to keep the patient load well balanced, the dental team productivity maximized with proper scheduling, and patients pleased because their time is respected. Stress throughout the dental practice is reduced because the dental team and the patients are happier with an efficiently running schedule. In many practices, there is a separate coordinator for the hygiene team and another coordinator for the dentist’s and assistants’ schedules.

Telephone Protocol

The administrative team member responsible for scheduling will spend a significant amount of time communicating with patients by telephone. Over ninety percent of all patients use the telephone as their first contact with a dental practice. First impressions are lasting and can make or break a practice. While a professional business appearance is essential, so is a professional telephone image. The team member responsible for taking telephone calls must be mindful that patients and prospective patients are listening rather than looking at the team member. Also, all callers need to be treated with the utmost respect. Consequently, it is essential to develop a professional telephone personality. To become effective on the telephone, the team member must:

- Keep a smile in one’s voice and face

- Answer calls promptly and speak clearly

- Be considerate, tactful, warm and receptive

- Ask questions discreetly

- Take messages respectfully

- Transfer calls carefully

- Place calls properly

- Avoid prejudice

When placing a patient on hold, the assistant should ask to be excused from the first caller before answering the second call, with the goal of returning to the first caller as soon as possible. Always wait for an answer from the caller before placing the caller on hold. Use a friendly salutation and identify the needs of the second caller, and if a short response can be given to the second caller, complete the call and return to the first caller. If the second call requires a lengthy conversation, explain that another call is on hold, ask the caller if he or she can wait, and then place him or her on hold. If the second caller does not wish to wait, make alternate arrangements requesting the best time and telephone number to return the call. The call should be returned promptly or at the approximate time requested by the caller. When returning to the original call, always thank the caller for waiting before proceeding with the conversation.

Appointment Scheduling

Patient schedules can be maintained through the use of a traditional appointment book (paper format) or through the use of a computerized schedule (paper-less format). In both methods, the schedule for one day is broken down into columns, with each column representing the number of treatment rooms being used or available.

In the dental practices that use the traditional appointment book format, there is usually a separate book for the scheduling of hygiene patients and another for the scheduling of the dentist’s appointments.

Time increments are referred to as units of time; a unit is usually 10, 15, or 20 minutes. There are six units per hour with a 10-minute increment system, four units per hour with a 15-minute increment system and three units for a twenty-minute increment system. Ten-minute units provide greater flexibility for patient scheduling; as a result, this increment is more common today than 15-minute units or the 20-minute units.

Traditional appointment books normally show 10 or 15-minute intervals of time, and can be formatted to show a week at a glance. Days and times the dental practice is closed can be crossed out, still showing the entire week’s schedule. Some dental practices will color code their scheduling of appointments to indicate which team member is rendering treatment. For example, if using a two surface amalgam restoration appointment, the schedule would reflect the first twenty minutes of the sixty-minute allotted time is the dentist to anesthetize and prepare the cavity preparation; the next twenty minutes for the restorative auxiliary to place and finish the restoration; the next 10 minutes for the dentist to check the restoration and the last 10 minutes are for the assistant to tear down and turn around the operatory. During the times the dentist is out of the operatory, other patients can be scheduled in another treatment room. This type of color-coding scheduling can also be utilized with some of the scheduling software programs available today.

Unlimited future booking allows appointments to be scheduled as far in advance as necessary to accommodate all patients. This requires careful advanced planning for the entire dental team, especially the hygiene staff members for time away from the practice since patients will typically book future appointments six, nine and sometime twelve months in advance. This method of booking is common among large dental practices with a substantial patient base.

Restricted appointment booking limits scheduling to a specified time period, such as one to three months out; patients who are not prescheduled during this time are added to a call list and are contacted when appointments become available. This system requires less advanced planning for the dental practice for taking time off, but can be a turn-off for patients who may end up waiting a long time for their appointments. This method can also be a nightmare for the scheduling coordinator in a dental practice with a large patient base.

Patient referrals - A licensed dentist is able to legally perform any dental treatment in the office. However, many dentists prefer to refer certain cases to a dental specialist. Specialty areas of dentistry include endodontics, periodontics, oral & maxillofacial surgery, orthodontics, pediatric dentistry, and dental public health.

As a courtesy, the dental assistant will often coordinate with a specialty office to make appointments for patients. Not only will the assistant call for the appointment, but may also forward a specific prescribed treatment order, any relevant information, and radiographic images to aid in patient treatment.

Scheduling Guidelines

After an appointment book or scheduling software is selected, a scheduling matrix or framework is often established. In the traditional method, the scheduling coordinator will begin crossing off days with an X that the dental practice is closed, individual team member’s vacations, and times the practice may close for team meetings or continuing education. It is recommended to use a pencil as plans may change especially in practices that book from six months to a year in advance. A scheduling matrix is also completed on computerized schedules, showing a darkened block of time and can be done for several years into the future. It is also helpful to make note of school holidays to schedule teachers and students so they do not miss school.

Lunch hours for the dental team are also blocked out. In some practices, lunches are staggered to best meet the needs of the practice’s patient base, while others close down during the noon hour as a whole. Lunches are also blocked with an X in traditional appointment books or with a darkened block of time on computerized schedules.

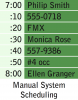

In order to assist the scheduling coordinator, the dentist should provide her/him with an appointment schedule list. This list will contain the procedures that are performed in the office (including the sequence for several step appointments, and the number of days required between appointments), and it will indicate the number of units required for each procedure. Scheduling guidelines can vary from dentist to dentist, even within the same dental practice, so it is important to know the desired length of appointment time. Figure 11 depicts a typical appointment screen found on a computerized system.

Frequently, the dental practice will also plan some buffer time into the daily schedule. Buffer time is set aside for the scheduling of emergency patients. Often, this time consists of one or two units in the late morning or late afternoon. An experienced schedule coordinator who is familiar with procedures may also be able to schedule emergencies by double booking patients. Double-booking means that two patients are scheduled at the same time, but they are both attended to by either the dentist or one of the team members. This system makes the greatest use of the dentist’s and the staff’s time. Double booking may also be used to schedule short appointments such as suture removal, denture adjustments, denture try-ins, or impressions for bleaching trays. This method is referred to as “dovetailing.”

The scheduling coordinator must also be aware of special appointment considerations such as the time of day to schedule certain procedures. For example, some practitioners prefer complicated procedures in the morning and some prefer them in the afternoon. It is important to know the doctor’s preference. Many dental hygienists prefer a regular recare appointment scheduled between two scaling and root planing procedures, to give the fingers a slight resting period. Knowing each member of the dental team’s optimum time will aid the assistant in scheduling patients. Staggering types of treatment appointments versus scheduling the same type of appointment repeatedly will keep the dental team and their schedule flowing smoothly. Figure 12 shows a schedule of a week at a glance with a day schedule in the inset.

The appointment times most frequently requested by patients are referred to as “prime times” and will vary from one practice to another. In most offices, this generally refers to late afternoon appointments, while for some; it is the first appointment of the day. It is obvious that not all who request this time will receive it, so patients must be informed of the need to schedule this time on a rotating basis. Certain patients may need special appointment arrangements, such as a diabetic patient needing to be scheduled after mealtime, or an elderly patient requiring a late afternoon appointment in order to arrange transportation with a working family member. Elderly patients should be scheduled for a time that is best for them, when they are not fatigued or tired. Weather conditions may also be a concern for this patient group, and appointment times in the morning often work well. Young children tend to do the best when appointments are scheduled in the morning or after nap times. School-aged children normally require appointments after school hours or vacation days. Being aware of winter and spring vacations or conference days for the various school districts in the dental practice’s area can assist the practice with best meeting the needs of these younger patients and their families. College-aged patients typically know if they will be home around the holidays or home in the spring for summer break and may schedule out pending travel plans. Being cognizant of all of these factors will help to make the day go more smoothly for all team members involved in patient care.

When scheduling patients it is important for the scheduling coordinator to remain in control of the appointment book. A good procedure to follow includes:

- Ask what day of the week is best;

- Next ask if morning or afternoon is best; and

- Then give them two choices

Too many choices may become confusing to patients who may be anxious.

Recording necessary data - Computerized scheduling allows the scheduling coordinator to input variables such as provider, day of the week and preferred time when searching for an appointment in the database. After finding the date and time convenient for the patient, data is keyed into the computer and the appointment is automatically scheduled, along with the patient’s contact information found in the database. Some programs offer the convenience of printing an appointment card at the time of appointment scheduling.

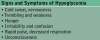

When scheduling using a manual system (Table 14), write in pencil because appointments do change. To schedule an appointment, it is important to do the following steps:

- Establish an appointment time and date with the patient

- Record the patient name and phone numbers, both home and business

- Record the age of the patient (if a child)

- Note the procedure to be completed

- Designate the amount of time needed with an arrow

Additionally, the entry should also have a notation for special considerations, such as for a new patient, the age of a child patient, parent or guardian’s name if a child patient, or if the patient requires any type of pre-medication. The patient must also be given an appointment card with the day, date, and time of the next appointment written in ink. After the appointment is noted in the schedule, the card is filled out, the appointment time is reconfirmed to be sure the information is the same on the schedule and on the patient’s card, and then the card is given to the patient. Never fill out the appointment card before placing it in the schedule. This is a safeguard against a patient showing up and not being listed in the schedule.

When a patient calls on the telephone to schedule an appointment, the same procedure is used for the traditional appointment book and computerized scheduling. As a courtesy, an appointment card may be mailed to the patient.

Appointment series - Certain dental procedures require subsequent appointments. Crown and bridge procedures typically require 10-14 days between the initial and insertion appointment, depending on the dental laboratory used. A denture or partial denture series require a number of appointments spread out over several weeks. Many patients prefer to book their appointments ahead of time guaranteeing them their preferred day and time that best works with their schedule. When possible, schedule a series of appointments on the same day and time of week. This makes it easier for patients to remember their appointments.