You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. Sign up today!

Forgot your password? Click Here!

Most dental hygiene programs are independent of schools of dentistry, suggesting that interprofessional collaboration between dentists and dental hygienists is challenged among graduates.1 There are 65 accredited dental schools in the United States; 27 have affiliated dental hygiene (DH) programs, and less than 10 have dental hygiene programs integrated within the school’s clinical program. A 2009 Swedish clinical teaching study reported that health professionals educated together obtain greater knowledge of other professions’ skills, communication, and teamwork philosophy.2 The practice model, described by Stolberg and colleagues, suggests that a strong, developed working relationship between a dentist and a dental hygienist strengthens productivity, individual work satisfaction, and continuity of care.1 According to the 2006 American Dental Education Association Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education, the vision of the dental healthcare team is clouded by the reality that students in separate health professions have minimal interaction with one another.3 Initiating teamwork between DH and dental students during their undergraduate education was reported to increase dental students’ knowledge about dental hygienists’ competence.4 Furthermore, improved patient outcomes were observed when students of medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, and physical therapy were trained together in a clinical setting as an interprofessional team.5 Educating dental and DH students together, which occurs more commonly outside of the United States, has resulted in successful working relationships in private practice.4-6

Currently, there is minimal research regarding knowledge and attitudes of US dental students related to dental hygienists’ contributions to optimal patient care in dental practice, particularly the influence of integrated entry-level education. The purpose of this quantitative, cross-sectional study was to assess senior dental students’ knowledge and attitudes toward dental hygienists’ contributions to optimal comprehensive patient care and to compare the responses of students from two dental schools, one with a DH program and one without a DH program.

Materials and Methods

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Review Board approved this cross-sectional study. The study population consisted of 474 senior dental students from two US dental schools, one with a DH program (363 students) and one without (111 students). At both dental schools there were 2-year International Dentist Programs. The second-year international program students participated in the clinical activities with the traditional fourth-year dental students. Thus, responses from both groups of dental students were combined. The schools were from different states, but the legal DH duties were the same, with the exception that nerve block injections were not allowed in the state of the school with a DH program.

The dental and DH students at the school with a DH program had two major sources of professional interaction. First, both groups of students participated in a class, in which they presented thorough courses of treatments for assigned patients with complex and extensive health histories. The students worked in groups of five, one from each of the following classes: DH, D1, D2, D3, and D4, with the DH student being responsible for oral hygiene instruction, nonsurgical periodontal treatment, and maintenance. Second, both groups shared the same clinic space, which facilitated collaboration of patient treatment. The dental students would refer their assigned patients to the DH student for DH care. If the DH student saw a patient who needed a procedure performed by a dental student, first, he/she would refer the patient to the dental student for the treatment.

The survey was developed and implemented utilizing Qualtrics7 survey software program. The survey instrument consisted of 15 items in the following domains: 1) Knowledge, including the routinely performed duties of a licensed dental hygienist (five multiple-choice questions); 2) Attitudes, including outcomes of collaborating with a dental hygienist and interest in hiring a dental hygienist in one’s future dental practice (five Likert-like questions); and 3) Demographic characteristics (five multiple-choice questions). The survey was pilot tested by five dental students, separate from the study sample, to ensure feasibility of the survey instrument and clarity of the items. The pilot survey was evaluated and the final instrument revised accordingly. The survey was administered to senior dental students from the school without DH during a designated class session. The researcher provided the potential subjects with a TinyURL link via Qualtrics software program, which allowed them to access the web-based survey without collecting personal identifiers. Informed consent was obtained on the first page of the survey, and survey submission was monitored through Qualtrics. At the school with DH, potential subjects were recruited in informal settings throughout the school premises. They were requested to complete a written copy of the survey, which included the informed consent on the first page of the survey. The researcher entered the resulting data into the study database without knowledge of any personal identifiers.

Results were expressed as frequencies of responses for each item on the survey. The chi-square test was used to compare responses of the two groups, and a P value of ≤.05 was used to indicate statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Results

The survey was completed by 95 senior dental students, which included students from the International Dentist Programs; 44 from a school without DH, and 51 from a school with DH. While the total enrollment of senior dental students of the two schools was 474, all students were not available the day of the survey administration due to externships and rotations outside the school premises. Thus, the number of potential subjects was 354, and the study’s response rate was 27%.

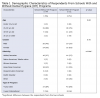

For both schools most of the respondents were in the 4-year DDS program and were between the ages of 25-29 (Table 1). The primary ethnic differences reported were a greater percentage of Asian respondents in the school without DH, and a higher percentage that selected “other” in the school with DH.

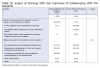

The responses of the two groups of dental students differed significantly on two major study outcomes (Table 2). Participants from the school with DH indicated greater agreement with the statement, “collaborating with DH students in school, has given, or would have given me, a better understanding of the value a dental hygienist brings to my future dental practice” (P = .02). Likewise, a significant difference (P = .01) was found to the statement, “having a DH program at a dental school leads to patients receiving more comprehensive preventive care.”

The extent of reported collaboration with DH students is indicated in Table 3. Respondents were allowed to select multiple responses to the phrase, “Working in collaboration with DH students results in . . .” Ninety percent of the respondents from the school with DH selected the response: “Providing optimal comprehensive patient care,” compared with 72% of those from the school without DH. Alternatively, a greater percentage from the school without DH than the school with DH selected “Developing a relationship of trust and respect between two professions” and “Increasing awareness of each profession’s responsibilities in the dental office.”

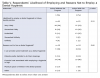

Table 4 demonstrates the respondents’ knowledge of the routine and nonroutine performed duties of a licensed dental hygienist. Most students in both groups knew that dental hygienists do dental cleanings, fluoride treatment application, and cannot write prescriptions. However, approximately half of the respondents from the school without DH did not know that the hygienist could perform the following: application of pit-and-fissure sealants, delivery of nitrous oxide-oxygen sedation, intra/extra-oral examination of soft tissue, and nonsurgical treatment of periodontal disease; whereas more than 78% of respondents from the school with DH were familiar with these DH duties. This difference was statistically significant (P < .001).

The responses from the two groups did not significantly differ to the statement, “How likely are you to employ a dental hygienist in your future clinical practice” (Table 5). Most of the subjects responded “very likely” or “somewhat likely.” However, the reasons for not hiring a dental hygienist varied between groups. More respondents in the school without DH than those in the school with DH cited “I can provide the same treatment as a dental hygienists”; and more respondents in the school with DH than those in the school without DH cited “Financial cost associated with employing a dental hygienist is high” (Table 5).

Discussion

This study compared senior dental students from a dental school with DH with those from a school without DH in terms of knowledge and attitudes toward dental hygienists’ contributions to optimal comprehensive patient care. More respondents from the school with DH than from the school without DH agreed that collaboration with DH students has, or would have, given them a better understanding of the value a dental hygienist brings to their future dental practice and that having a DH program at a dental school leads to patients receiving more comprehensive preventive care.

Interprofessional Education (IPE), as defined by the Centre for Advancement in Interprofessional Education, takes place when two or more professions learn with, from, and about each other in order to improve collaboration and the quality of practice.8 Our findings are consistent with those of others, who reported that IPE enables students from other professions to obtain knowledge, skills, and attitudes from professions outside their own.9,10 Leisnart and colleagues demonstrated that dental students had increased understanding and appreciation of DH students merely after sharing patients, planning, and performing treatment together.4 Shared learning experiences during their professional education were reported to contribute to an overall more positive outcome for collaboration in their future professional roles together.4,11 Curran and colleagues found that students from various healthcare professions, including medicine, nursing, and pharmacy, agreed that they had improved attitudes toward teamwork and increased knowledge of what different professions can offer when they had constant exposure to one another during their professional education.12 Our results further support these studies in that more respondents from the school with DH than from the school without DH strongly agreed that being educated with dental hygienists will lead to patients receiving more optimal comprehensive patient care.

Respondents from the school with DH did not overwhelmingly select “developing a relationship of trust and respect between the two professions.” This finding is important because it implies that having two professional programs on the same campus, or in the same building, is not sufficient to develop these attributes. It is likely that to develop trust and respect it would be necessary to foster personal interactions between interested individuals in a supportive environment. Understanding of another’s profession may be foundational to creating trust and respect. To familiarize the students with one another’s skills a more extensive integration would need to have occurred. For example, adding more courses or seminars for DH and dental students to attend together, enhancing the sharing of patient care, and collaborating on more case presentations would provide more educational integration. This approach has recently been developed and evaluated, as reported in a recent abstract; the authors stated that both dental and DH students felt that the combination of clinical collaboration coupled with communication and teamwork skills training was valuable to their training.13 Using the Attitudes to Health Professionals Questionnaire, researchers from Denmark studied the attitudes among students from different healthcare professions working together (ie, students from nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and medicine).5 These researchers found that an educational intervention, involving a 2-week interprofessional training unit working with real patients, was able to develop more positive attitudes toward the other healthcare professionals.5 The respondents from the school with DH in our study would have lacked this intensive intervention.

The level to which the dental and DH students worked together may not have been substantial, even with a DH program at the institution. Most respondents from the school with DH referred their patients to the DH student for dental cleanings. However, less than a quarter received referrals from DH students for their patients with restorative needs, and only one student worked together with a DH student to develop a treatment plan for the patient. While both groups of dental student respondents were in support of collaboration with DH students, this support appears not to have been actualized. Patient care has been shown to improve by incorporating IPE into schools’ curricula for students in medicine, dentistry, and nursing14; however, our findings agree that IPE opportunities need to be made available for the collaboration of dental and DH students.

Klefbom and colleagues suggest that working together in entry-level education could be a way to enhance knowledge of respective dental professions’ specific competencies.15 However, in our study only approximately half the respondents selected “Increasing awareness of each profession’s responsibilities in the dental office” as a result of collaboration with DH students. It has been reported that in order to have a successful collaborative team between dentists and dental hygienists, it is critical that both disciplines be familiar with what each can contribute and are capable of doing.16 Thus, educating dental students in a school with a DH program would increase their exposure to DH students, and expand their knowledge of the others’ scope of practice. Responses to the item identifying the routine and nonroutine performed duties of a dental hygienist indicated that respondents from the school with DH were more familiar with the scope of practice of a licensed dental hygienist. Most, but not all, respondents from the school without DH knew the traditional care provided by dental hygienists, such as dental cleanings, but lacked knowledge that hygienists are allowed to administer nitrous oxide-oxygen sedation, or perform extra/intra-oral examination of soft tissues. These respondents did not fully comprehend the extensive skills that a dental hygienist has been educated to perform. A greater understanding of the dental hygienists’ skills and expertise is gained when dental students collaborate with DH students in the clinics. This concept is supported by a study, recently reported in abstract format; dental students in the lower classes, who presumably had not experienced working with DH students in the clinic, were not fully aware of the dental hygienists’ scope of practice.17

While most respondents agreed that collaborating with DH students leads to patients receiving more comprehensive preventive care, only approximately half, regardless of whether their school had a DH program or not, indicated that they would be very likely to hire a dental hygienist in their future dental practices. The respondents who were less likely to hire a hygienist agreed the primary reason was because of their perceptions of the high financial cost associated with employing a dental hygienist. These results indicate that more education regarding the contributions of dental hygienists to not only comprehensive patient care and risk management, but also to the economics of private practice, is required to understand the value a dental hygienist can bring to their practices. In a survey of California dentists as to the reasons why they employ or do not employ a dental hygienist, most dentists cited “personal preferences.”18 These preferences could have been developed during their dental education, especially if they lacked collaboration with DH students, or if they had ever practiced in a country where the role of the dental hygienist was ill defined. More respondents from the school without DH than the one with DH agreed that they would not hire a dental hygienist because they could provide the same treatment as a dental hygienist. In order for clinic patients in a dental school without DH to receive comprehensive care, these dental students must perform the traditional care provided by a dental hygienist based on their knowledge of such care. These students perhaps are being socialized to the concept of dentists performing dental hygiene care in the absence of knowledge of a dental hygienist’s specialized skills. A hygienist’s expertise in oral health promotion and disease prevention offers significant benefits to comprehensive patient care within a dental practice.

The ability to generalize these findings is limited due to the low response rate, which can be attributed to multiple factors. Recruiting dental students to participate in this study proved to be more challenging than anticipated. Many students were on rotations and externships, making it impossible to reach them during a class session. Some students were absent or late to class. It seems that the dental students did not perceive the value of the study and, thus, did not prioritize participation in their busy lives. Access to dental student time to obtain survey responses limited the number of responses. Moreover, it was not possible to collect the data in the same manner from both schools, and the lack of a standard data collection procedure may have contributed to response bias. Another limitation could have been investigator bias. Unintentionally the investigators may have phrased some of the questions in ways that may have led the respondents to answer in a particular biased direction.

Conclusion

In this study more respondents from the dental school with a DH program had greater knowledge of the routine and nonroutine performed duties of a licensed dental hygienist, as well as expressed more positive attitudes toward DH students’ role in delivering comprehensive preventive care in the dental school clinic. Based on these results, it is concluded that these future dentists would be more familiar with the specific tasks to be delegated so that together, as a team, they could provide optimal comprehensive patient care. These dental students from the dental school with a DH program seem to have a better understanding of the value a dental hygienist would bring to their future dental practice. More studies are necessary to establish a need for improved collaboration between dental and DH students. By creating more opportunities for dental and DH students to interact during their entry-level education, both professionals can learn of each other’s contributions to patient care, which may ultimately lead to improved comprehensive patient care.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Sanaz Nojoumi, RDH, MS, is a graduate of the Dental Hygiene Program at the University of California, San Francisco. Gwen Essex, RDH, MS, EdD, is the Health Science Clinical Professor, Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Sciences, University of California, San Francisco. Dorothy J. Rowe, RDH, MS, PhD, is Associate Professor Emeritus, Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Sciences, University of California, San Francisco.

REFERENCES

1. Stolberg RL, Bilich LA, Heidel M. Dental team experience (DTE): A five year experience. J Dent Hyg. 2012;86(3):223-230.

2. Hallin K, Kiessling A, Waldner A, Henriksson P. Active interprofessional education in a patient based setting increases perceived collaborative and professional competence. Med Teach. 2009;31(2):151-157.

3. Haden NK, Andrieu SC, Chadwick DG, et al. The dental education environment. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(12):1265-1270.

4. Leisnert L, Karlsson M, Franklin I, et al. Improving teamwork between students from two professional programmes in dental education. Euro J Dent Educ. 2012;16(1):17-26.

5. Jacobsen F, Lindqvist S. A two-week stay in an interprofessional training unit changes students’ attitudes to health professionals. J Interprofess Care. 2009;23(3):242-250.

6. Ritchie C, Dann L, Ford PJ. Shared learning for oral health therapy and dental students: Enhanced understanding of roles and responsibilities through interprofessional education. Euro J Dent Educ. 2013;17(1):e56-e63.

7. Qualtrics. 2014 ed. of the Qualtrics Research Suite. Copyright ©2005 Qualtrics. Qualtrics and all other Qualtrics products or service names are registered trademarks of Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA: http://www.qualtrics.com.

8. CAIPE (Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education). 2014 [revised Definition; cited 2014 Dec 27]. [Internet]. http://www.caipe.org.uk/aboutus/defining-ipeenglish.

9. Funnell P. Exploring the value of interprofessional shared learning. Interprofessional Relations in Health Care. 1995:163-171.

10. Haber J, Spielman AI, Wolff M, Shelley D. Interprofessional education between dentistry and nursing: the NYU experience. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2014;42(1):44-51.

11. Morison S, Marley J, Machniewski S. Educating the dental team: Exploring perceptions of roles and identities. Br Dent J. 2011;211(10):477-483.

12. Curran VR, Mugford JG, Law R, MacDonald S. Influence of an interprofessional HIV/AIDS education program on role perception, attitudes and teamwork skills of undergraduate health sciences students. Educ Health. 2005;18(1):32-44.

13. Patterson E, Hagel N, Perry K, et al. A pilot dental teamwork course focused on interprofessional competencies. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(2):213-214.

14. Formicola AJ, Andrieu SC, Buchanan JA, et al. Interprofessional education in U.S. and Canadian dental schools: an ADEA team study group report. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(9):1250-1268.

15. Klefbom C, Wenestam CG, Wikstrom M. What dental care are the dental hygienists allowed to perform? J Swedish Dent Assoc. 2005;10:66-73.

16. Swanson Jaecks KM. Current perceptions of the role of dental hygienists in interdisciplinary collaboration. J Dent Hyg. 2009;83(2):84-91.

17. McComas M, Inglehart MR. Dental, dental hygiene, and graduate students and faculty perspectives on dental hygienists’ professional role and the potential contribution of a peer teaching program. J Dent Educ. 2016;80(9):1049-1061.

18. Pourat N. Differences in characteristics of California dentists who employ dental hygienists and those who do not. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(8):1027-1035.